Uncategorized

The Post-Pandemic r*

The debate about the natural rate of interest, or r*, sometimes overlooks the point that there is an entire term structure of r* measures, with short-run…

The debate about the natural rate of interest, or r*, sometimes overlooks the point that there is an entire term structure of r* measures, with short-run estimates capturing current economic conditions and long-run estimates capturing more secular factors. The whole term structure of r* matters for policy: shorter run measures are relevant for gauging how restrictive or expansionary current policy is, while longer run measures are relevant when assessing terminal rates. This two-post series covers the evolution of both in the aftermath of the pandemic, with today’s post focusing especially on long-run measures and tomorrow’s post on short-run r*.

There is arguably some evidence that short-run r* is currently elevated relative to pre-COVID levels: The economy has proven to be extremely resilient and spreads remain relatively low, in spite of the recent banking turmoil. Estimates from the New York Fed DSGE model, which we discuss in tomorrow’s post, confirm this assessment. As shown in June, the model expects short-run real r* to be 2.5 percent by the end of the year. Evidence on whether long-run r*—that is, the persistent component, or trend, in r*—has risen after COVID is much weaker. We use a battery of models, from VARs to DSGEs, to estimate these trends, and these models reach different conclusions. According to VAR models, long-run r* has roughly remained constant and, if anything, declined a bit since late 2019, reaching 0.75 percent in real terms. According to the DSGE model, long-run r* has instead risen by almost 50 basis points during this period, and is now about 1.8 percent.

Long-Run r*: Different Answers from Different Models

The chart below shows the trends in r* obtained from two models presented in this Brookings paper by Del Negro, Giannone, Giannoni, and Tambalotti (2017). The two models are a “trendy” VAR (or, VAR with common trends; black dashed line) and a DSGE (blue dashed line) model capable of capturing low-frequency movements in productivity growth and the convenience yield. A key result of that paper, reproduced in the chart below with updated data, was that up to the mid-2010s these two very different methodologies delivered nearly identical results. After the pandemic, the estimates diverge notably however, with the VAR estimates trending down slightly, and the DSGE estimates trending up sharply.

The Low-Frequency Component of r* in the VAR and DSGE Models

Note: The dashed black (blue) lines show the posterior medians and the shaded gray (blue) areas show the 68 percent posterior coverage intervals for the VAR (DSGE) estimates of the low-frequency component of the real natural rate of interest.

The table below reports numerical values of the changes in the r* trends (that is, long-run r*) according to a variety of models. It shows that from the fourth quarter of 2019 (pre-COVID) to the second quarter of 2023 the trend in r* has decreased by a little more than 10 basis points, according to the baseline trendy VAR. For a variant of this VAR where we also use data on consumption growth and hence make inference on trend growth, the decline is a bit larger at 20 basis points. According to the DSGE, long-run r* instead went up by almost 50 basis points after COVID. We also report the results from the global trendy VAR proposed by Del Negro, Giannone, Giannoni, and Tambalotti (2019). According to this model, which is estimated with annual data from seven advanced countries, both world and U.S. long-run r* rose by about 15 basis points from 2019 to 2022, although the increase is not significant.

The pre-COVID decline in long-run r* since the late 1990s is very similar to that reported in the Brookings paper, where the sample ends in 2016. According to the trendy VAR, long-run r* had fallen pre-COVID by a little more than 1.5 percentage points. The VAR with consumption implied a larger decline of almost 2 pp, while according to the DSGE the decline was about 1 pp. Because of the divergence in the post-COVID trends the overall decline in r* becomes a bit larger according to the two VAR models—1 and 1.75 pp, respectively—but falls to about 60 basis points according to the Brookings DSGE model.

Change in Long-Run r* According to Different Models

| Post-COVID Change 2023:Q2-2019:Q4 | |||

| r*t | –cyt | gt | |

| VAR | -0.14 (-0.15, -0.12) Pr>0: 9 | -0.06 (-0.09, -0.04) Pr>0: 20 | |

| VAR with cons. | -0.19 (-0.22, -0.18) Pr>0: 7 | -0.07 (-0.11, -0.05) Pr>0: 21 | -0.10 (-0.13, -0.09) Pr>0: 16 |

| Brookings DSGE | 0.48 (0.06, 0.89) Pr>0: 98 | 0.28 (-0.01, 0.57) Pr>0: 96 | 0.20 (-0.04, 0.48) Pr>0: 94 |

| Global VAR | 0.14 (-0.44, 0.71) Pr>0: 68 | ||

| Pre-COVID Decline 2019:Q4–1988:Q1 | |||

| r*t | –cyt | gt | |

| VAR | -1.61 (-1.78, -1.34) Pr<0: 99 | -0.94 (-1.05, -0.89) Pr<0: 99 | |

| VAR with cons. | -1.88 (-2.08, -1.52) Pr<0: 99 | -0.73 (-0.83, 0.66) Pr<0: 99 | -1.02 (-1.13, -0.86) Pr<0: 99 |

| Brookings DSGE | -1.03 (-1.51, -0.54) Pr<0: 99 | -0.60 (-1.05, -0.14) Pr<0: 99 | -0.39 (-0.62, -0.20) Pr<0: 99 |

| Global VAR | -1.69 (-3.27, -0.14) Pr<0: 98 | ||

| Post-COVID Decline 2023:Q2–1998:Q1 | |||

| r*t | –cyt | gt | |

| VAR | -1.75 (-1.93, -1.46) Pr<0: 99 | -1.01 (-1.13, -0.93) Pr<0: 99 | |

| VAR with cons. | -2.07 (-2.30, -1.71) Pr<0: 99 | -0.81 (-0.93, -0.71) Pr<0: 99 | -1.12 (-1.26, -0.95) Pr<0: 99 |

| Brookings DSGE | -0.55 (-0.99, -0.24) Pr<0:99 | -0.31 (-0.73, 0.09) Pr<0: 93 | -0.19 (-0.44, 0.05) Pr<0: 94 |

| Global VAR | -1.56 (-3.17, 0.02) Pr<0: 97 |

Note: For each trend, the table reports the posterior median and the 95 percent (parentheses) posterior coverage intervals, as well as the posterior probability in percentage points that the change is positive (for the 2023:Q2-2019:Q4 period) or negative (for the 2019:Q4-1998:Q1 and 2023:Q2-1998:Q1 periods).

The Term Structure of r* in the DSGE Model

What drives these differences across models? Since much of the post-COVID action takes place in the DSGE model, we turn to this model in order to understand its interpretation of the data. The chart below shows the entire term structure of r* according to the model—namely the short-run r* and the 5-year, 10-year, and 30-year r* measures (which we have so far referred to as long-run r*), where the x-year r* is the expected value of r* x-years ahead (that is, the x-years r* is a forward rate). While the short-run r* is very volatile, its fluctuations capture well the state of the business cycle in the U.S.: short-run r* is low during recessions or periods of stagnation (for example, early 1990s, early 2000s, the great recession and its aftermath, and the COVID recession) and high when the economy is booming. Of late, the U.S. economy has remained extremely resilient even as monetary policy has tightened, as discussed in tomorrow’s post, and the estimates of r* are elevated.

The chart also shows that while the volatility of the r* measure not surprisingly diminishes with the horizon–5-year is less volatile than short-run r*, 10-year is less volatile than 5-year, and so on—all these measures are correlated with one another. This observation points to an important difference between trendy VAR and DSGE estimates of long run r*. While by design the trendy VAR separates the trend from the cycle—in econometric parlance, the model performs a trend/cycle decomposition—in the DSGE model all the various frequencies are inextricably linked. This does not mean that longer run DSGE measures of r* move with each and every movement of short-run r*—in the 1990s recession for instance short-run r* falls quite a bit but the other measures do not budge. However, it appears that in the DSGE, movements in short-run r* tend to have some information for longer run measures, while in the trendy VAR this information is ignored.

The Term Structure of r* in the DSGE Model

We conclude this post by relating the DSGE estimates to the r* estimates from Laubach and Williams (2003, LW) and Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2017, HLW), obtained with post-COVID data using the approach in Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2023). The chart below plots the time series of these measures together with the 5-year DSGE r*, which in the Brookings paper we found to be most correlated with the LW and HLW measures. The chart shows that the LW and HLW r* estimates declined sharply with the Great Recession, going from about 2.5 to 1 percent, after which they remain roughly steady at about 1 percent. The DSGE 5-year r* tracks the LW and HLW measures well from the early 1990s to the early 2010s. It then continues to decline going below zero, but eventually rises to a level comparable to that of the LW model at the end of the sample.

DSGE 5-Year r* and the LW and HLW Measures

Conducting inference on latent variables such as r* is a difficult business, as any estimate is inherently model dependent. In many circumstances the different models agree: for instance, there is widespread evidence that r* declined from the mid-1990s until the aftermath of the Great Recession and remained low until the COVID pandemic. Approaches disagree in terms of assessing what happened afterward, with models relying more on long-run averages indicating that long-run r* remained low, while approaches such as the DSGE where short- and long-run measures are more tightly connected indicate that long-run r* has risen. Tomorrow’s post focuses on short-run r* and its implications for the economy.

Katie Baker is a former senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Logan Casey is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Del Negro is an economic research advisor in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Aidan Gleich is a former senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Ramya Nallamotu is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Katie Baker, Logan Casey, Marco Del Negro, Aidan Gleich, and Ramya Nallamotu, “The Post-Pandemic r*,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, August 9, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/08/the-post-pandemic-r/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Uncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

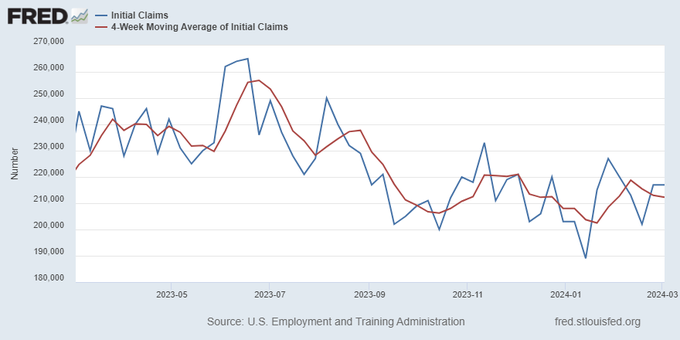

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

Uncategorized

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives…

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives floating around corporate media platforms has been the argument that the American people “just don’t seem to understand how good the economy really is right now.” If only they would look at the stats, they would realize that we are in the middle of a financial renaissance, right? It must be that people have been brainwashed by negative press from conservative sources…

I have to laugh at this notion because it’s a very common one throughout history – it’s an assertion made by almost every single political regime right before a major collapse. These people always say the same things, and when you study economics as long as I have you can’t help but throw up your hands and marvel at their dedication to the propaganda.

One example that comes to mind immediately is the delusional optimism of the “roaring” 1920s and the lead up to the Great Depression. At the time around 60% of the U.S. population was living in poverty conditions (according to the metrics of the decade) earning less than $2000 a year. However, in the years after WWI ravaged Europe, America’s economic power was considered unrivaled.

The 1920s was an era of mass production and rampant consumerism but it was all fueled by easy access to debt, a condition which had not really existed before in America. It was this illusion of prosperity created by the unchecked application of credit that eventually led to the massive stock market bubble and the crash of 1929. This implosion, along with the Federal Reserve’s policy of raising interest rates into economic weakness, created a black hole in the U.S. financial system for over a decade.

There are two primary tools that various failing regimes will often use to distort the true conditions of the economy: Debt and inflation. In the case of America today, we are experiencing BOTH problems simultaneously and this has made certain economic indicators appear healthy when they are, in fact, highly unstable. The average American knows this is the case because they see the effects everyday. They see the damage to their wallets, to their buying power, in the jobs market and in their quality of life. This is why public faith in the economy has been stuck in the dregs since 2021.

The establishment can flash out-of-context stats in people’s faces, but they can’t force the populace to see a recovery that simply does not exist. Let’s go through a short list of the most faulty indicators and the real reasons why the fiscal picture is not a rosy as the media would like us to believe…

The “miracle” labor market recovery

In the case of the U.S. labor market, we have a clear example of distortion through inflation. The $8 trillion+ dropped on the economy in the first 18 months of the pandemic response sent the system over the edge into stagflation land. Helicopter money has a habit of doing two things very well: Blowing up a bubble in stock markets and blowing up a bubble in retail. Hence, the massive rush by Americans to go out and buy, followed by the sudden labor shortage and the race to hire (mostly for low wage part-time jobs).

The problem with this “miracle” is that inflation leads to price explosions, which we have already experienced. The average American is spending around 30% more for goods, services and housing compared to what they were spending in 2020. This is what happens when you have too much money chasing too few goods and limited production.

The jobs market looks great on paper, but the majority of jobs generated in the past few years are jobs that returned after the covid lockdowns ended. The rest are jobs created through monetary stimulus and the artificial retail rush. Part time low wage service sector jobs are not going to keep the country rolling for very long in a stagflation environment. The question is, what happens now that the stimulus punch bowl has been removed?

Just as we witnessed in the 1920s, Americans have turned to debt to make up for higher prices and stagnant wages by maxing out their credit cards. With the central bank keeping interest rates high, the credit safety net will soon falter. This condition also goes for businesses; the same businesses that will jump headlong into mass layoffs when they realize the party is over. It happened during the Great Depression and it will happen again today.

Cracks in the foundation

We saw cracks in the narrative of the financial structure in 2023 with the banking crisis, and without the Federal Reserve backstop policy many more small and medium banks would have dropped dead. The weakness of U.S. banks is offset by the relative strength of the U.S. dollar, which lures in foreign investors hoping to protect their wealth using dollar denominated assets.

But something is amiss. Gold and bitcoin have rocketed higher along with economically sensitive assets and the dollar. This is the opposite of what’s supposed to happen. Gold and BTC are supposed to be hedges against a weak dollar and a weak economy, right? If global faith in the dollar and in the U.S. economy is so high, why are investors diving into protective assets like gold?

Again, as noted above, inflation distorts everything.

Tens of trillions of extra dollars printed by the Fed are floating around and it’s no surprise that much of that cash is flooding into the economy which simply pushes higher right along with prices on the shelf. But, gold and bitcoin are telling us a more honest story about what’s really happening.

Right now, the U.S. government is adding around $600 billion per month to the national debt as the Fed holds rates higher to fight inflation. This debt is going to crush America’s financial standing for global investors who will eventually ask HOW the U.S. is going to handle that growing millstone? As I predicted years ago, the Fed has created a perfect Catch-22 scenario in which the U.S. must either return to rampant inflation, or, face a debt crisis. In either case, U.S. dollar-denominated assets will lose their appeal and their prices will plummet.

“Healthy” GDP is a complete farce

GDP is the most common out-of-context stat used by governments to convince the citizenry that all is well. It is yet another stat that is entirely manipulated by inflation. It is also manipulated by the way in which modern governments define “economic activity.”

GDP is primarily driven by spending. Meaning, the higher inflation goes, the higher prices go, and the higher GDP climbs (to a point). Eventually prices go too high, credit cards tap out and spending ceases. But, for a short time inflation makes GDP (as well as retail sales) look good.

Another factor that creates a bubble is the fact that government spending is actually included in the calculation of GDP. That’s right, every dollar of your tax money that the government wastes helps the establishment by propping up GDP numbers. This is why government spending increases will never stop – It’s too valuable for them to spend as a way to make the economy appear healthier than it is.

The REAL economy is eclipsing the fake economy

The bottom line is that Americans used to be able to ignore the warning signs because their bank accounts were not being directly affected. This is over. Now, every person in the country is dealing with a massive decline in buying power and higher prices across the board on everything – from food and fuel to housing and financial assets alike. Even the wealthy are seeing a compression to their profit and many are struggling to keep their businesses in the black.

The unfortunate truth is that the elections of 2024 will probably be the turning point at which the whole edifice comes tumbling down. Even if the public votes for change, the system is already broken and cannot be repaired without a complete overhaul.

We have consistently avoided taking our medicine and our disease has gotten worse and worse.

People have lost faith in the economy because they have not faced this kind of uncertainty since the 1930s. Even the stagflation crisis of the 1970s will likely pale in comparison to what is about to happen. On the bright side, at least a large number of Americans are aware of the threat, as opposed to the 1920s when the vast majority of people were utterly conned by the government, the banks and the media into thinking all was well. Knowing is the first step to preparing.

The second step is securing your own financial future – that’s where physical precious metals can play a role. Diversifying your savings with inflation-resistant, uninflatable assets whose intrinsic value doesn’t rely on a counterparty’s promise to pay adds resilience to your savings. That’s the main reason physical gold and silver have been the safe haven store-of-value assets of choice for centuries (among both the elite and the everyday citizen).

* * *

As the world moves away from dollars and toward Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), is your 401(k) or IRA really safe? A smart and conservative move is to diversify into a physical gold IRA. That way your savings will be in something solid and enduring. Get your FREE info kit on Gold IRAs from Birch Gold Group. No strings attached, just peace of mind. Click here to secure your future today.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International13 hours ago

International13 hours agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges