Government

Rising from the Ashes: FDA Grants EUA to Invivyd COVID-19 Antibody

The FDA has authorized Invivyd’s Pemgarda™ (pemivibart), indicated for prevention of COVID-19 in adults and adolescents ages 12 and older.

The post Rising…

With the FDA granting emergency use authorization (EUA) to Invivyd’s lead candidate, a monoclonal antibody (mAb) designed to prevent COVID-19 in immunocompromised adults and adolescents, the company has succeeded in its two-year quest to rise from the ashes of its predecessor Adagio Therapeutics.

The FDA authorized Pemgarda (pemivibart), a mAb re-engineered from Adagio’s failed lead candidate ADG20—which Invivyd is still working to develop under the name adintrevimab.

Pemgarda is indicated for prevention of COVID-19 in adults and adolescents ages 12 and older, weighing at least 40 kg (88 pounds) with moderate-to-severe immune compromise due to certain medical conditions or effects of certain immunosuppressive medications or treatments, and are unlikely to mount an adequate immune response to COVID-19 vaccination.

Invivyd plans to detail how it will make Pemgarda available to patients “within a week or so,” CEO Dave Hering told GEN Edge.

Hering said Invivyd will initially focus its commercial efforts on a 485,000-person slice of the nation’s nine million immunocompromised people who are moderately to severely immunocompromised, and thus at highest risk for COVID-19. Of that 485,000, more than two-thirds (332,000 or 68%) have various blood cancers, while 86,000 (18%) are solid organ transplant recipients (liver, lung, and kidney), and the remaining 67,000 (14%) are stem cell transplant recipients.

Defined population

That defined population, Invivyd reasons, will help Pemgarda to succeed in a field of COVID-19 drugs and vaccines whose sales have shriveled as the pandemic evolved into an endemic.

Pfizer’s top-selling COVID-19 antibody Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir and ritonavir) saw its sales crater 93% last year, to $1.279 billion from $18.933 billion in 2022, while its top-selling COVID-19 vaccine Comirnaty® (COVID-19 Vaccine, mRNA), co-developed with BioNTech, plunged 70%, to $11.22 billion from $37.806 billion. Moderna’s Spikevax® vaccine sales skidded 64%, to $6.671 billion from $18.435 billion.

“We see still that the need for ongoing COVID-19 products is basically going to meet a leveling off point. But for monoclonal antibodies, we think that there’s a tremendous ramp up, whereas for a lot of the other products, vaccines or antivirals, that were heavily utilized, they’re coming down,” Hering said. “We’ll reach a new status quo because monoclonal antibodies haven’t been on the market at the same level that the vaccines and antivirals have been. That is why we think that there is still a tremendous amount of need and increase for mAbs.”

Invivyd has hired a sales and marketing leadership team consisting of a vp of sales and regional sales managers, with 20–25 contracted key account managers (KAMs) now being engaged and trained. The KAMs will target the estimated 1,150 U.S. institutions that provide care to about 70% of the 485,000 moderately to severely immunocompromised patients that are the company’s initial focus.

“A good chunk of those KAMs already have accepted offers, though not all of them,” Hering said. “We’re in the process of onboarding them and training them to be able to have them be ready to be out in the field and interacting with HCPs [healthcare providers] in the very near term.”

Pemgarda’s list price had yet to be set at deadline, and Invivyd has not issued a sales forecast for the antibody.

Pemgarda differs from adintrevimab by eight amino acids within the variable region—a difference that allows it to shift slightly where it binds with the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. That change makes Pemgarda much better able than adintrevimab to prevent symptomatic COVID-19 as the virus rapidly evolves, forming new variants, according to Invivyd.

“Always ensure binding”

“By shifting these amino acids, what we’re doing is slightly modifying where the antibody binds to the virus,” Hering explained. “We want to always ensure binding, because once you have binding, that is what really leads to the neutralization of the virus in the blood.”

The re-engineering also allowed Invivyd to apply a new regulatory framework for its Phase III trial allowing “immunobridging” through the use of data from serum-neutralizing titers as, well as previously generated clinical trial data from a prototype mAb—in this case, adintrevimab.

The evidence underpinning Pemgarda’s EUA included data showing that immunobridging was established in the Phase III CANOPY pivotal trial (NCT06039449), designed to assess the drug’s ability to protect against symptomatic COVID-19 at a 4,500 mg dose. Invivyd showed that the calculated serum neutralizing antibody titers against JN.1—now the dominant COVID-19 variant in the United States according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—were consistent with the titer levels associated with efficacy in prior clinical trials of monoclonal antibodies, including adintrevimab.

As it announced the EUA, Invivyd also released additional exploratory data from CANOPY that showed clinical protection from symptomatic COVID-19 stretching 90 days in all but one of the 314 patients dosed with Pemgarda—an open-label cohort with moderate-to-severe immune-compromised patients.

By contrast, eight patients randomized to placebo showed RT-PCR-confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 in a cohort of 159 adults without moderate-to-severe immune compromise who were at risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 due to regular unmasked face-to-face interactions in indoor settings.

The data was not part of Invivyd’s EUA filing or its review by the FDA, though the company said it may use the data to generate hypotheses for future discovery and development of Pemgarda.

“We’ll use the data as we think through future trials,” Hering said. “We keep having conversations with the FDA to better understand what the path would be for a BLA [Biologics License Application]”.

Annual updates

Among Invivyd’s goals, he added, is obtaining FDA approval for a license that would enable the company to update its vaccines annually in response to new or resurging variants, as with influenza vaccines: “We continue to feel that the virus will evolve and mutate, and at some point will require an updated mAb. So, we want to have a pathway to be able to do that going forward.”

Pemgarda was developed using INVYMAB, Invivyd’s platform approach which combines viral surveillance and predictive modeling with advanced antibody engineering. INVYMAB is designed to enable rapid, serial generation of durable mAbs targeting conserved epitopes that could be deployed to keep pace with SARS-CoV-2 viral evolution or other viruses.

Investors initially roared their approval of the FDA EUA decision with a buying surge that sent Invivyd shares soaring 41% on Friday, from $3.09 to $4.36, before the stock succumbed to profit-taking, dropping 26% to $3.23 on Monday. While the surge did not reach the stock’s all-time high closing price of $5.04 on February 8, Invivyd remains close to the level it has traded at since it more than doubled, zooming 120% from $1.63 to $3.59 on December 18.

That day, Invivyd announced initial positive data from CANOPY in which Pemgarda—then named VYD222—produced high serum virus neutralizing antibody (sVNA) titer levels against the Omicron XBB.1.5 variant of COVID-19 in a cohort of approximately 300 patients who were significantly immunocompromised. The results essentially replicated the titer levels observed in the company’s Phase I trial (NCT05791318), showing that a single administration of VYD222 was generally well-tolerated in healthy adult volunteers at all three dose levels tested with no serious adverse events. All dose levels tested showed robust neutralization activity against Omicron XBB.1.5 at Day 7.

Invivyd submitted its EUA request to the FDA in early January.

Adintrevimab and Pemgarda are the only two named candidates listed in Invivyd’s pipeline. The company has three other COVID-19 mAb candidates, identified only as #2, #3, and #4, in discovery and preclinical phases—plus a mAb combination candidate for prevention of influenza, in the early discovery phase.

Adintrevimab remains under development for both COVID-19 prevention and COVID-19 treatment. Adintrevimab trials for both conditions have concluded, and Invivyd says it has a package of data ready to submit for an EUA filing dependent on variant susceptibility.

“One of the things we keep doing from the research side is testing it against new variants. So, that continues, and we’re always looking to see what its activity would be against some of those variants,” Hering said. “It is something that we continue to actively monitor and look at.”

The post Rising from the Ashes: FDA Grants EUA to Invivyd COVID-19 Antibody appeared first on GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News.

grants pandemic covid-19 cdc disease control emergency use authorization vaccine treatment testing fda clinical trials preclinical genetic antibodies ritonavir monoclonal antibodiesInternational

Goldman Sachs weighs in on commodity prices ahead of rate cuts

Commodity prices are often volatile over short periods.

Over extremely long periods – centuries – commodities prices are pure inflation hedges. That means their inflation-adjusted returns are about zero.

But over shorter periods, commodity prices are extremely volatile. For example, they tanked in early 2020 amid the pandemic outbreak. They climbed sharply from March 2020 to June 2022 and have mostly slipped since then.

Commodity investors maintain that the asset is uncorrelated to stocks and bonds and can thus provide a significant diversifier to your portfolio. But commodities often trade in line with the economy.

A strong economy stimulates demand for commodities, including oil, copper, grains and cocoa, because consumers and companies are flush with cash to spend. Similarly, a weak economy depresses demand for commodities.

Investors have been buying commodities

The asset class has strengthened in recent weeks, as signs of economic recovery have emerged worldwide. The Bloomberg Commodity Index has ascended 3.5% in the last month.

Related: Analysts issue unexpected crude oil price forecast after surge

The two most-followed commodities, oil and gold, have helped lead the way. You may have seen the impact of rising oil prices at your gas pump. The national regular gas price averaged $3.53 Monday, up 8% from a month ago.

Gold has hit a record high above $2,200, buoyed by Chinese demand. The People’s Bank of China purchased more gold than any other central bank last year, according to the World Gold Council, an industry group.

It’s not just big-time commodities taking off. Cocoa prices have surpassed a 46-year-old record peak. Bad weather in West Africa crimped supply, while speculative fervor has sparked demand, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Goldman Sachs analysts weigh in on commodities

Goldman Sachs analysts believe the commodities rally will continue. Their reasons:

1. What they call “cyclical” support.

“With the trough in global manufacturing behind us and our economists’ strong conviction of interest rate cuts in the U.S. and Europe [starting in June], we expect further support to commodities demand and prices,” the analysts said. Lower rates generally lift economic growth.

Copper, aluminum, and oil products should show particular strength, they said.

More Economic Analysis:

- Bond markets tell Fed rate story that stocks still ignore

- February inflation surprises with modest uptick, but core pressures ease

- Vanguard unveils bold interest rate forecast ahead of Fed meeting

2. Then there are “structural” factors. For example, strong demand for green metals, those that are used to make clean energy, and increasing supply concerns have pushed copper prices to a one-year high, the analysts said. They forecast a 40% increase for copper this year.

3. Geopolitical factors, such as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, are also relevant, as they limit commodity supply.

“The ongoing Red Sea shipping disruptions and recent attacks on Russian oil-refining capacity” illustrate how geopolitical turmoil is boosting commodity prices, the analysts said.

Another commodity bull is Bruce Kamich, a technical analyst for TheStreet.com’s Pro service. He sees demographic trends supporting commodities.

“Since 2000, hundreds of millions of people have moved into the middle class, and that is fueling demand that we have never seen before,” he wrote.

“This insatiable demand is hitting against stagnant supplies of food and materials. I anticipate that commodities will be rationed by price in the years ahead.”

Kamich is looking for an upward move in commodity prices starting in August.

To be sure, the Goldman analysts warn against loading up on every commodity. They have a bearish view for this year on natural gas and lithium. And they see little change for nickel and zinc.

If you are going to invest in commodities, you might consider purchasing a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund ETF with a diversified portfolio. That can protect you against the plunge of an individual commodity.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

economic recovery economic growth pandemic bonds stocks fed etf recovery commodities gold oil africa europe ukraine chinaInternational

Apple CEO Tim Cook woos China as part of big Asia pitch

Apple needs China, and other markets in Asia, now more than ever.

Apple (AAPL) shares closed lower Monday, extending a notable 2024 decline for the world's second-largest company as it balances the challenges of aggressive regulations in Europe and the U.S. and a realigning of its broader position in Asian markets.

CEO Tim Cook wraps up a five-day visit to China, as part of the tech giant's renewed Asia push, early this week to revive growth in the world's biggest smartphone market — which also happens to host the most critical elements of its global supply chain.

Last week, Cook opened the company's newest flagship Apple Store in Shanghai, the second-largest behind its Fifth Avenue location in New York and met with key suppliers and government officials including Commerce Minister Wang Wentao ahead of a key business development summit that ended Monday.

China remains one of the most important markets for Apple, accounting for around 20% of its global sales, pegged last year at around $386 billion, although that share has fallen steadily since 2015 and has largely plateaued since the COVID pandemic of 2020.

Increased competition from lower-priced rivals and a drive by Beijing to bolster the fortunes of state-backed Huawei Technologies have added to Apple's China-sale challenge, as have the ongoing trade tensions with the U.S. and Washington's move to limit the export of high-end technologies.

Apple's China sales pressures

Reports have suggested that Beijing has banned the use of iPhones by government employees and state-backed enterprises to support the launch of Huawei's new Mate 60 handset.

Apple's fourth quarter 2023 China sales fell nearly 13% from a year earlier, the company reported in February, even as global iPhone revenue surprised to the upside at just under $70 billion.

The decline prompted a rare move from Apple to cut the price of its new iPhone 15 by around $70, or 5%, as part of a Lunar New Year promotion in late January.

Cook said Apple would launch its new Vision Pro headset in China later this year, telling CCTV that he remains "very confident" regarding domestic market prospects.

“I love China, I love being here, I love the people and the culture," Cook said on a broadcast streamed through CCTV's Weibo social media account. "Every time I come here, I am reminded that anything is possible here.”

However, Cook needs to balance the need for a robust sales base in China and the support of officials in Beijing with its broader Asia efforts as it gingerly retools its supply chain to locations in Vietnam, Thailand, and India. The goal is to reduce its reliance on a single location — and to ease the political risk tied to tensions between Beijing and Taiwan.

Related: Goldman Sachs analysts unveil a big change to Apple's outlook

"There's no supply chain in the world that's more critical to us than China," Cook reportedly told the state-controlled China Daily over the weekend, but the group's recent push into India suggests it's playing a much longer game.

"The timing of this trip was important as, in essence, Apple needs China and China needs Apple despite all the noise," said Wedbush analyst Dan Ives. "Apple needs to turn this headwind into a tailwind heading into the iPhone 16 release this fall and it all starts with reaffirming Apple's presence" in the world's second-largest economy.

Apple's journey: A passage to India

At the same time, however, Cook is shrewdly making inroads into India, an economy boasting more than a billion citizens and a huge, largely untapped, iPhone market.

Apple doesn't break out India sales separately, but Cook said revenue hit a record last quarter, and data from CounterPoint Research suggests it topped more than 10 million iPhone shipments in the Android-dominated market last year.

Its overall market share, however, is only around 6.5%, well south of the 20% stake it commands in China, according to International Data Corp. figures. That provides a huge opportunity for sales growth over the coming years.

India Prime Minister Narendra Modi also wants to see that nation become a major export hub for smartphones, and he has courted Apple and others in setting up new manufacturing bases, including an iPhone 15 assembly facility, run by Taiwan-based Foxconn, in Tamil Nadu.

That may be why his government reversed an earlier rule earlier this month, following intense lobbying from the U.S., to require laptop makers to obtain licenses for all shipments into the estimated $8 billion a year market.

Apple faces the long arm of regulatory law

Apple's Asia fortunes could be even more critical over the coming years as it grapples with a slowdown in U.S. demand, which some have tied to its lack of new product innovation, and an intensifying regulatory environment in key Western markets.

EU regulators, which have long held U.S. tech giants in their crosshairs, opened an antitrust probe into Apple this week under the region's newly enforced Digital Markets Act.

Related: Apple hit by massive music streaming fine (it's big)

Last week in the U.S., Attorney General Merrick Garland unveiled details of an antitrust suit that accused the tech giant of running a monopoly in the smartphone market that if left unchallenged "will only continue to strengthen."

"We do see an increasing likelihood that AAPL will be forced to incrementally open up its ecosystem over time across all geographies but view monopolistic claims as a bit of a reach," said CFRA analyst Angelo Zino.

"All eyes will be on whether recent changes in Europe and the pending U.S. litigation will impact the growth trajectory of Apple's high-margin services business."

The weakening sales, tepid innovation and long-armed regulators have combined to shave more than $300 billion from Apple's market value this year, with the shares falling more than 8% and trailing only Tesla TSLA as the worst-performing Magnificent 7 stock.

More Tech Stocks:

- Google fined $270 million by French regulatory authority

- Analysts revamp Nvidia price targets as Blackwell tightens AI market grip

- Analysts overhaul Micron stock price target ahead of earnings

Ives at Wedbush, however, sees the recent events as strengthening the case for Apple's renewed Asia push, noting that China's recent foreign investment slump and moribund domestic economy make the two necessary if wary, bedfellows.

"Cupertino is facing regulatory battles from all directions," Ives said. "And while China has been a headache for Apple over the past year, it appears to be changing its tune as the threat of Apple taking its supply chain outside China has been heard loud and clear from Beijing."

"We have seen Apple's back against the wall before and we view this period as just another chapter in the Apple growth story with AI now on the doorstep," he added.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic india europe eu chinaGovernment

Capital Confusion at the New York Times

In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution claims that the merger between Capital One and Discover would…

In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution claims that the merger between Capital One and Discover would “keep intact the broken and predatory system in which credit card companies profit handsomely by rewarding our richest Americans and advantaging the biggest corporations.”

That’s quite an indictment! Fortunately, Klein also offers solutions. Phew!

But really, it’s difficult to understand how someone could describe the highly innovative, dynamic, and efficient U.S. credit-card system as “broken.” If it were, why would U.S. credit-card networks like Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover be the world leaders, accounting for more than 60% of global market share?

And far from being “predatory,” credit cards have been hugely valuable to American families at all income levels. During the pandemic, they literally saved lives by enabling people in lockdown to buy food online and have it delivered to their homes. As Klein himself notes:

The pandemic changed how we buy things, significantly increasing the share of transactions put on credit cards rather than conducted in cash.

Klein tries to turn this positive into a negative, noting that the increase in card use added “to the swipe fees merchants pay.” What he fails to mention is that the switch from cash to credit has, in general, reduced merchants total costs because the costs of handling cash are so much higher. When a customer pays in cash, checkout takes longer than paying with a card (especially where the transaction is contactless). For larger stores, that means more cash-register operators must be hired. For smaller stores, it means there are less resources available to perform other tasks, such as taking inventory or restocking shelves.

Cash also presents a greater risk of theft, which means merchants must invest in security systems both in-store and for moving cash to the bank. And cash must be counted and deposited, both of which take time.

Study after study has shown that, when all relevant costs are taken into account, cash costs merchants more than payment cards. A 2018 study by the IHL Group, for example, found that the cost of accepting cash averaged about 9% and ranged from 4.7% for larger grocery stores to 15.5% for bars and restaurants. By contrast, the all-in cost of processing credit-card payments is typically less than 3%.

Klein’s sources don’t inspire much confidence. The link in his opening paragraph is not to an academic study, but to a video on the Times’ own website that spins an elaborate tale of how a frying pan bought using credit-card rewards was actually paid for by MJ, the owner of a local convenience store. In essence, the video asserts that, by using a rewards credit card to buy $100 of goods every week for a year at MJ’s store, enough rewards were accrued to pay for the frying pan.

Let’s suppose that the bank that issued the rewards card charged the maximum interchange fee on the transactions at MJ’s store, which in 2023 was 3.15%. Further assume that MJ’s merchant-account provider charges her on an “interchange-plus” basis. If MJ used Helcim, she would pay the interchange fee plus 0.4%, plus $0.08 per transaction.

So, of the $5,200 spent over the course of the year by the customer using a rewards card, $163.80 would go to the issuing bank and $28.80 to Helcim, leaving MJ with a net of $5,007.40. By contrast, if MJ had been paid in cash, she would have a net of $4,768.4 (based on the average costs identified by IHL for convenience stores of 8.3%).

While the Times video wants our hearts to bleed for MJ having to pay for a customer’s All-Clad D5 12” frying pan, had the customer paid her in cash instead, she would have made $239 less. And the customer would have been less happy, because he would have effectively paid about $250 more (the cost of the pan). In other words, paying with cash would make the merchant and the consumer worse off to the tune of nearly $500.

Credit cards also have other benefits that Klein ignores in his simplistic story. By providing credit—including up to 45 days interest free for cardholders who pay off their balance each month—credit cards enable people to smooth their spending so that they can buy items even when they don’t have money in the bank. They also provide fraud and theft protection for the cardholder, making it far less risky to carry a card than a bundle of cash. Many cards also include payment-protection insurance, rental-car insurance, and travel insurance.

Finally, credit cards make it far easier to trace payments, because the card issuer knows the identity and address of the legitimate user. This makes it more difficult to make illegal purchases using credit cards (compared to relatively untraceable cash) and easier to enforce sales taxes.

This highlights a fundamental problem with Klein’s analysis: he counts the costs of paying with credit cards but fails to explain for what would happen in the alternative. He wants us to believe that:

the rest of us, whether we pay with cash, a debit-card or a middle-of-the-road credit card, wind up paying more—because we are subsidizing these rewards cards for whom only the wealthiest qualify.

Except that’s just not true.

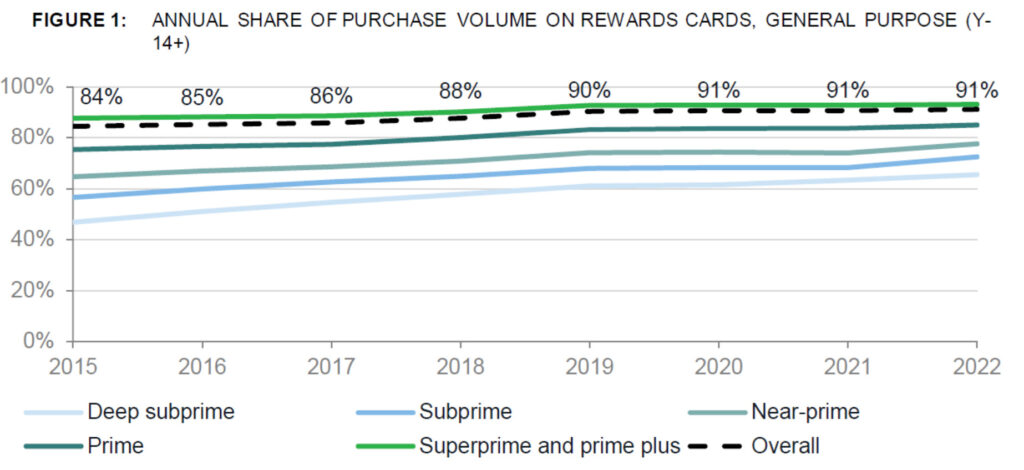

First, as noted, in most cases, cash purchases are more costly for store owners, so credit-card users are subsidizing cash users. Second, as Todd Zywicki, Ben Sperry, and I have noted, and as can be seen in the figure below from the most recent Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) report on the consumer credit-card market, access to rewards credit cards is less a function of income and more a function of the cardholder’s credit score. Third, as the figure also shows, more than 90% of all credit-card transactions are made using rewards cards.

Fourth, as can be seen in the chart below, and as the CFPB noted in the accompanying text: “Earning rates are about the same across credit score tiers for those with rewards cards, except for consumers with scores above 800.” Perhaps Mr. Klein does not have access to those higher-value rewards cards, but if so, he is the exception, not the rule.

These data suggest that, for all the critics’ bluster, the value of rewards per dollar spent varies relatively little from card to card; what differs is the types of rewards and other associated benefits. Innovations along these lines have been important drivers in the shift from cash and checks to credit cards, with attendant benefits for consumers, merchants, and society as a whole.

Nonetheless, Klein is correct that the fees charged for different cards can vary significantly. In fact, importantly, the story is rather more complicated than Klein makes out. Interchange fees typically vary not only by card, but also by type of merchant. This is, at least in part, because different merchants pose different risks of fraud and chargeback.

Moreover, in contrast to Klein’s assertion that low-dollar sales typically have high fees, networks often discount the fees on small-ticket items in order to encourage adoption. For transactions of $15 or less, Visa’s small-ticket interchange fee for credit cards carries no fixed-fee component. For transactions of $5 or less, Mastercard’s fixed fee is only $0.04. And in some cases, such as for gasoline purchases, they cap the total amount (for example, Mastercard charges a maximum of $0.95 and Visa a maximum of $1.10 for gas).

Nonetheless, Klein offers the anecdote that, one year, his “oldest friend’s small coffee shop paid more in card processing costs than for coffee beans.” In fairness, the coffee shop in question, Bump n Grind in Maryland, roasts its own beans, and therefore buys green beans that are considerably less expensive than pre-roasted beans. It also sells much more than just coffee, including vinyl records. So it probably has many costs that are higher than the amount it pays for beans, including: rent, equipment, utilities, and staff.

It may also use a merchant acquirer or a payment gateway (such as Square or Stripe) that offers blended rates (that is, a single rate for all transactions regardless of the type of card or size of transaction), which would mean that it is unable to take advantage of the small-ticket discount available on “interchange-plus” plans.

‘Solutions’ Far Worse Than the ‘Problem’

Klein lays much of the blame on the U.S. Supreme Court for the alleged problem of consumers being charged different swipe fees for different cards issued on the same payment network. He claims that “a 2018 Supreme Court ruling effectively forces merchants to accept either every type of card – from, say, a basic Green Card to the Platinum Card – from an issuer like Amex or none of them.” And he goes on to assert that “the ruling also barred merchants from incentivizing consumers to use cheaper ones.”

There’s just one problem with these claims: they’re not true.

What the Supreme Court did in Ohio v. Amex was to prevent the state from overriding the contractual “anti-steering” provisions that had long been established by credit-card networks in their agreements with merchants (either directly, in the case of three-party cards such as Amex and Discover, or via agreements with issuers, in the case of four-party cards like Visa and Mastercard). The Court explained its rationale clearly:

Respondent… Amex… operate[s] what economists call a “two-sided platform,” providing services to two different groups (cardholders and merchants) who depend on the platform to intermediate between them. Because the interaction between the two groups is a transaction, credit-card networks are a special type of two-sided platform known as a “transaction” platform. The key feature of transaction platforms is that they cannot make a sale to one side of the platform without simultaneously making a sale to the other. Unlike traditional markets, two-sided platforms exhibit “indirect network effects,” which exist where the value of the platform to one group depends on how many members of another group participate. Two-sided platforms must take these effects into account before making a change in price on either side, or they risk creating a feedback loop of declining demand. Thus, striking the optimal balance of the prices charged on each side of the platform is essential for two-sided platforms to maximize the value of their services and to compete with their rivals.

Visa and MasterCard—two of the major players in the credit-card market—have significant structural advantages over Amex. Amex competes with them by using a different business model, which focuses on cardholder spending rather than cardholder lending. To encourage cardholder spending, Amex provides better rewards than the other credit-card companies. Amex must continually invest in its cardholder rewards program to maintain its cardholders’ loyalty. But to fund those investments, it must charge merchants higher fees than its rivals. Although this business model has stimulated competitive innovations in the credit-card market, it sometimes causes friction with merchants. To avoid higher fees, merchants sometimes attempt to dissuade cardholders from using Amex cards at the point of sale—a practice known as “steering.” Amex places antisteering provisions in its contracts with merchants to combat this.

While these anti-steering provisions are important, they are not the provisions to which Klein refers, which are known as “honor-all-cards” provisions and which prevent merchants from discriminating against cards bearing the network’s brand. Nonetheless, honor-all-cards provisions are likewise important to the functioning of two-sided payment networks (as Nobel laurate economist Jean Tirole has noted) because they enable card networks to create a range of offerings, thereby facilitating innovation by and competition among issuers.

Without the honor-all-cards provisions, merchants might refuse to accept cards with higher interchange fees. Klein seems to think this is a good idea. He proposes that:

Congress should legislatively correct the Supreme Court’s mistake. For starters, give merchants the power to reject the priciest credit cards, and let’s see if their users are willing to pay the true cost of their rewards.

But this would result in a race to the bottom in which card issuers were unable to offer rewards or otherwise differentiate their products, leading to a decline in the use of cards. This, in turn, would reduce spending, harming both consumers and merchants.

Klein supports his argument that Congress could override the honor-all-cards provision by citing the Durbin amendment, which imposed price controls on debit-interchange fees. A recent study by Vladimir Mukharlyamov of Georgetown University and Natasha Sarin of the University of Pennsylvania found that this had the effect of reducing covered banks’ annual revenues by about $5.5 billion. Seeking to recoup some of the lost revenue, banks on average doubled their monthly fees on checking accounts; increased the minimum deposit required for “free” checking by 21%; and reduced the availability of accounts with no-minimum free checking by about half.

Likely as a direct consequence, hundreds of thousands of the poorest Americans left the banking system altogether. Meanwhile, merchants passed through little, if any, of the savings resulting from the reduced debit-interchange fees, so those on low incomes who kept their accounts but paid monthly fees were measurably worse off.

To make matters worse, Klein wants “brave policymakers” to “start taxing reward points.” At least he is clear that this is really just about taxing the rich:

The richer you are, the more likely you qualify for bigger rewards. Progressive taxation rates mean that exempting rewards from taxation makes them nearly four times as valuable to those in the top tax bracket as the bottom.

As it happens, some credit-card rewards probably are taxable; it depends on their function. But if policymakers were to make all rewards taxable, it would harm those that function primarily as rebates and loyalty incentives—such as airline miles received on co-branded cards. And that, in turn, would harm the co-brand partners, such as airlines and hotels.

Klein’s final proposal is more troubling. He suggests that “we could require all merchants have access to the same swipe-fee pricing, regardless of size.” His concern here is that some larger merchants leverage their bargaining power to obtain lower interchange fees. In part, larger merchants benefit from economies of scale and can implement transaction monitoring and security systems that smaller merchants simply can’t afford.

Meanwhile, a few large merchants (such as Costco) operate membership-based systems that enable them to forego customer convenience and strike exclusive deals with specific card issuers and networks, thereby obtaining lower swipe fees. Neither of these apply to individual smaller merchants, so the suggestion that swipe fees could be reduced by mandate to the levels negotiated by larger merchants is totally unrealistic.

In his last few paragraphs, Klein returns to the merger between Capital One and Discover, the hook around which he has hung a series of shibboleths about credit cards that he uses as the premise for his terrible policy proposals. And here again, he repeats those shibboleths, moaning that:

Capital One already seems to be competing with American Express for wealthy customers who like elite airport lounges and bit travel perks …

And in the next paragraph:

As the economy continues to digitize with more micropayments, the credit card burden will keep growing, particularly on smaller businesses.

And in the final paragraph:

Until legislators are willing to change the system that showers tax-free rewards on the upper middle class, the cash register will continue to exacerbate the wealth gap.

What utter tosh.

The post Capital Confusion at the New York Times appeared first on Truth on the Market.

link pandemic congress lockdown-

Spread & Containment2 weeks ago

Spread & Containment2 weeks agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International3 weeks ago

International3 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoParexel CEO to retire; CAR-T maker AffyImmune promotes business leader to chief executive

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoKey Events This Week: All Eyes On Core PCE Amid Deluge Of Fed Speakers

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoA Blue State Exodus: Who Can Afford To Be A Liberal