Government

Capital Confusion at the New York Times

In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution claims that the merger between Capital One and Discover would…

In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution claims that the merger between Capital One and Discover would “keep intact the broken and predatory system in which credit card companies profit handsomely by rewarding our richest Americans and advantaging the biggest corporations.”

That’s quite an indictment! Fortunately, Klein also offers solutions. Phew!

But really, it’s difficult to understand how someone could describe the highly innovative, dynamic, and efficient U.S. credit-card system as “broken.” If it were, why would U.S. credit-card networks like Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover be the world leaders, accounting for more than 60% of global market share?

And far from being “predatory,” credit cards have been hugely valuable to American families at all income levels. During the pandemic, they literally saved lives by enabling people in lockdown to buy food online and have it delivered to their homes. As Klein himself notes:

The pandemic changed how we buy things, significantly increasing the share of transactions put on credit cards rather than conducted in cash.

Klein tries to turn this positive into a negative, noting that the increase in card use added “to the swipe fees merchants pay.” What he fails to mention is that the switch from cash to credit has, in general, reduced merchants total costs because the costs of handling cash are so much higher. When a customer pays in cash, checkout takes longer than paying with a card (especially where the transaction is contactless). For larger stores, that means more cash-register operators must be hired. For smaller stores, it means there are less resources available to perform other tasks, such as taking inventory or restocking shelves.

Cash also presents a greater risk of theft, which means merchants must invest in security systems both in-store and for moving cash to the bank. And cash must be counted and deposited, both of which take time.

Study after study has shown that, when all relevant costs are taken into account, cash costs merchants more than payment cards. A 2018 study by the IHL Group, for example, found that the cost of accepting cash averaged about 9% and ranged from 4.7% for larger grocery stores to 15.5% for bars and restaurants. By contrast, the all-in cost of processing credit-card payments is typically less than 3%.

Klein’s sources don’t inspire much confidence. The link in his opening paragraph is not to an academic study, but to a video on the Times’ own website that spins an elaborate tale of how a frying pan bought using credit-card rewards was actually paid for by MJ, the owner of a local convenience store. In essence, the video asserts that, by using a rewards credit card to buy $100 of goods every week for a year at MJ’s store, enough rewards were accrued to pay for the frying pan.

Let’s suppose that the bank that issued the rewards card charged the maximum interchange fee on the transactions at MJ’s store, which in 2023 was 3.15%. Further assume that MJ’s merchant-account provider charges her on an “interchange-plus” basis. If MJ used Helcim, she would pay the interchange fee plus 0.4%, plus $0.08 per transaction.

So, of the $5,200 spent over the course of the year by the customer using a rewards card, $163.80 would go to the issuing bank and $28.80 to Helcim, leaving MJ with a net of $5,007.40. By contrast, if MJ had been paid in cash, she would have a net of $4,768.4 (based on the average costs identified by IHL for convenience stores of 8.3%).

While the Times video wants our hearts to bleed for MJ having to pay for a customer’s All-Clad D5 12” frying pan, had the customer paid her in cash instead, she would have made $239 less. And the customer would have been less happy, because he would have effectively paid about $250 more (the cost of the pan). In other words, paying with cash would make the merchant and the consumer worse off to the tune of nearly $500.

Credit cards also have other benefits that Klein ignores in his simplistic story. By providing credit—including up to 45 days interest free for cardholders who pay off their balance each month—credit cards enable people to smooth their spending so that they can buy items even when they don’t have money in the bank. They also provide fraud and theft protection for the cardholder, making it far less risky to carry a card than a bundle of cash. Many cards also include payment-protection insurance, rental-car insurance, and travel insurance.

Finally, credit cards make it far easier to trace payments, because the card issuer knows the identity and address of the legitimate user. This makes it more difficult to make illegal purchases using credit cards (compared to relatively untraceable cash) and easier to enforce sales taxes.

This highlights a fundamental problem with Klein’s analysis: he counts the costs of paying with credit cards but fails to explain for what would happen in the alternative. He wants us to believe that:

the rest of us, whether we pay with cash, a debit-card or a middle-of-the-road credit card, wind up paying more—because we are subsidizing these rewards cards for whom only the wealthiest qualify.

Except that’s just not true.

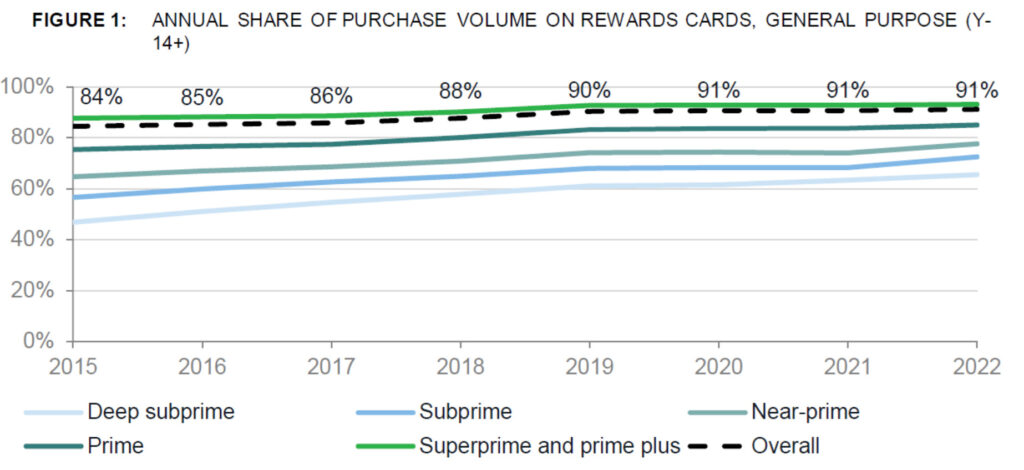

First, as noted, in most cases, cash purchases are more costly for store owners, so credit-card users are subsidizing cash users. Second, as Todd Zywicki, Ben Sperry, and I have noted, and as can be seen in the figure below from the most recent Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) report on the consumer credit-card market, access to rewards credit cards is less a function of income and more a function of the cardholder’s credit score. Third, as the figure also shows, more than 90% of all credit-card transactions are made using rewards cards.

Fourth, as can be seen in the chart below, and as the CFPB noted in the accompanying text: “Earning rates are about the same across credit score tiers for those with rewards cards, except for consumers with scores above 800.” Perhaps Mr. Klein does not have access to those higher-value rewards cards, but if so, he is the exception, not the rule.

These data suggest that, for all the critics’ bluster, the value of rewards per dollar spent varies relatively little from card to card; what differs is the types of rewards and other associated benefits. Innovations along these lines have been important drivers in the shift from cash and checks to credit cards, with attendant benefits for consumers, merchants, and society as a whole.

Nonetheless, Klein is correct that the fees charged for different cards can vary significantly. In fact, importantly, the story is rather more complicated than Klein makes out. Interchange fees typically vary not only by card, but also by type of merchant. This is, at least in part, because different merchants pose different risks of fraud and chargeback.

Moreover, in contrast to Klein’s assertion that low-dollar sales typically have high fees, networks often discount the fees on small-ticket items in order to encourage adoption. For transactions of $15 or less, Visa’s small-ticket interchange fee for credit cards carries no fixed-fee component. For transactions of $5 or less, Mastercard’s fixed fee is only $0.04. And in some cases, such as for gasoline purchases, they cap the total amount (for example, Mastercard charges a maximum of $0.95 and Visa a maximum of $1.10 for gas).

Nonetheless, Klein offers the anecdote that, one year, his “oldest friend’s small coffee shop paid more in card processing costs than for coffee beans.” In fairness, the coffee shop in question, Bump n Grind in Maryland, roasts its own beans, and therefore buys green beans that are considerably less expensive than pre-roasted beans. It also sells much more than just coffee, including vinyl records. So it probably has many costs that are higher than the amount it pays for beans, including: rent, equipment, utilities, and staff.

It may also use a merchant acquirer or a payment gateway (such as Square or Stripe) that offers blended rates (that is, a single rate for all transactions regardless of the type of card or size of transaction), which would mean that it is unable to take advantage of the small-ticket discount available on “interchange-plus” plans.

‘Solutions’ Far Worse Than the ‘Problem’

Klein lays much of the blame on the U.S. Supreme Court for the alleged problem of consumers being charged different swipe fees for different cards issued on the same payment network. He claims that “a 2018 Supreme Court ruling effectively forces merchants to accept either every type of card – from, say, a basic Green Card to the Platinum Card – from an issuer like Amex or none of them.” And he goes on to assert that “the ruling also barred merchants from incentivizing consumers to use cheaper ones.”

There’s just one problem with these claims: they’re not true.

What the Supreme Court did in Ohio v. Amex was to prevent the state from overriding the contractual “anti-steering” provisions that had long been established by credit-card networks in their agreements with merchants (either directly, in the case of three-party cards such as Amex and Discover, or via agreements with issuers, in the case of four-party cards like Visa and Mastercard). The Court explained its rationale clearly:

Respondent… Amex… operate[s] what economists call a “two-sided platform,” providing services to two different groups (cardholders and merchants) who depend on the platform to intermediate between them. Because the interaction between the two groups is a transaction, credit-card networks are a special type of two-sided platform known as a “transaction” platform. The key feature of transaction platforms is that they cannot make a sale to one side of the platform without simultaneously making a sale to the other. Unlike traditional markets, two-sided platforms exhibit “indirect network effects,” which exist where the value of the platform to one group depends on how many members of another group participate. Two-sided platforms must take these effects into account before making a change in price on either side, or they risk creating a feedback loop of declining demand. Thus, striking the optimal balance of the prices charged on each side of the platform is essential for two-sided platforms to maximize the value of their services and to compete with their rivals.

Visa and MasterCard—two of the major players in the credit-card market—have significant structural advantages over Amex. Amex competes with them by using a different business model, which focuses on cardholder spending rather than cardholder lending. To encourage cardholder spending, Amex provides better rewards than the other credit-card companies. Amex must continually invest in its cardholder rewards program to maintain its cardholders’ loyalty. But to fund those investments, it must charge merchants higher fees than its rivals. Although this business model has stimulated competitive innovations in the credit-card market, it sometimes causes friction with merchants. To avoid higher fees, merchants sometimes attempt to dissuade cardholders from using Amex cards at the point of sale—a practice known as “steering.” Amex places antisteering provisions in its contracts with merchants to combat this.

While these anti-steering provisions are important, they are not the provisions to which Klein refers, which are known as “honor-all-cards” provisions and which prevent merchants from discriminating against cards bearing the network’s brand. Nonetheless, honor-all-cards provisions are likewise important to the functioning of two-sided payment networks (as Nobel laurate economist Jean Tirole has noted) because they enable card networks to create a range of offerings, thereby facilitating innovation by and competition among issuers.

Without the honor-all-cards provisions, merchants might refuse to accept cards with higher interchange fees. Klein seems to think this is a good idea. He proposes that:

Congress should legislatively correct the Supreme Court’s mistake. For starters, give merchants the power to reject the priciest credit cards, and let’s see if their users are willing to pay the true cost of their rewards.

But this would result in a race to the bottom in which card issuers were unable to offer rewards or otherwise differentiate their products, leading to a decline in the use of cards. This, in turn, would reduce spending, harming both consumers and merchants.

Klein supports his argument that Congress could override the honor-all-cards provision by citing the Durbin amendment, which imposed price controls on debit-interchange fees. A recent study by Vladimir Mukharlyamov of Georgetown University and Natasha Sarin of the University of Pennsylvania found that this had the effect of reducing covered banks’ annual revenues by about $5.5 billion. Seeking to recoup some of the lost revenue, banks on average doubled their monthly fees on checking accounts; increased the minimum deposit required for “free” checking by 21%; and reduced the availability of accounts with no-minimum free checking by about half.

Likely as a direct consequence, hundreds of thousands of the poorest Americans left the banking system altogether. Meanwhile, merchants passed through little, if any, of the savings resulting from the reduced debit-interchange fees, so those on low incomes who kept their accounts but paid monthly fees were measurably worse off.

To make matters worse, Klein wants “brave policymakers” to “start taxing reward points.” At least he is clear that this is really just about taxing the rich:

The richer you are, the more likely you qualify for bigger rewards. Progressive taxation rates mean that exempting rewards from taxation makes them nearly four times as valuable to those in the top tax bracket as the bottom.

As it happens, some credit-card rewards probably are taxable; it depends on their function. But if policymakers were to make all rewards taxable, it would harm those that function primarily as rebates and loyalty incentives—such as airline miles received on co-branded cards. And that, in turn, would harm the co-brand partners, such as airlines and hotels.

Klein’s final proposal is more troubling. He suggests that “we could require all merchants have access to the same swipe-fee pricing, regardless of size.” His concern here is that some larger merchants leverage their bargaining power to obtain lower interchange fees. In part, larger merchants benefit from economies of scale and can implement transaction monitoring and security systems that smaller merchants simply can’t afford.

Meanwhile, a few large merchants (such as Costco) operate membership-based systems that enable them to forego customer convenience and strike exclusive deals with specific card issuers and networks, thereby obtaining lower swipe fees. Neither of these apply to individual smaller merchants, so the suggestion that swipe fees could be reduced by mandate to the levels negotiated by larger merchants is totally unrealistic.

In his last few paragraphs, Klein returns to the merger between Capital One and Discover, the hook around which he has hung a series of shibboleths about credit cards that he uses as the premise for his terrible policy proposals. And here again, he repeats those shibboleths, moaning that:

Capital One already seems to be competing with American Express for wealthy customers who like elite airport lounges and bit travel perks …

And in the next paragraph:

As the economy continues to digitize with more micropayments, the credit card burden will keep growing, particularly on smaller businesses.

And in the final paragraph:

Until legislators are willing to change the system that showers tax-free rewards on the upper middle class, the cash register will continue to exacerbate the wealth gap.

What utter tosh.

The post Capital Confusion at the New York Times appeared first on Truth on the Market.

link pandemic congress lockdownInternational

A top Disney World rival is planning to implement ‘surge pricing’

The popular theme park attraction is planning to follow in the footsteps of its competitor, and fans may not be happy about the move.

Disney World rival Legoland may be the next popular institution to implement a major change to its pricing that consumers have recently been extremely resistant to.

Scott O’Neil, the CEO of Merlin Entertainments, which owns Legoland, Madame Tussauds and Peppa Pig Theme Park, just revealed in a new interview with The Financial Times that his company is currently developing a dynamic pricing model, better known as “surge pricing,” for its attractions. Dynamic pricing is when the price of a product/service is adjusted based on the time of day and other factors such as consumer habits and demographics.

Related: Wendy’s is planning a major price change, and customers aren’t happy

O’Neil claims in the interview that the change will make customers pay more for tickets at its attractions during peak summer weekends than on rainy weekends in the off-season. The change will take place at its top 20 global attractions by the end of the year, and in major U.S. attractions next year.

“If [an attraction] is in the UK, it’s August peak holiday season, sunny and a Saturday, you would expect to pay more than if it was a rainy Tuesday in March,” said O’Neil.

O’Neil also revealed during the interview that the dynamic pricing model will help the company make up for the money it lost during the Covid pandemic as it experienced a decrease in foot traffic at its attractions.

In a recent report of the company's performance, Merlin Entertainments reveals that it's seeing a normalization of consumer demand at its theme parks.

“With no material COVID-19 related attraction closures remaining, our operational footprint has now largely returned to pre-pandemic levels,” said the company in the report.

If Legoland implements dynamic pricing, it won’t be the first major theme park to do so. Since 2018, Disney has used dynamic pricing to charge more money for tickets at its theme parks on busy days and less for days with lower attendance. Disneyland and Disney World are notorious for increasing their ticket prices on weekends and holidays to help push fans to visit the attractions on days with decreased demand.

The idea of dynamic pricing has recently caused an uproar amongst consumers. Fast-food chain Wendy’s (WEN) recently angered its customers last month after its CEO Kirk Tanner revealed during an earnings call in February that the company “will begin testing more enhanced features like dynamic pricing” as early as 2025.

Social media users called Wendy’s “greedy” for its plan to test out the change and even threatened to boycott its restaurants.

After facing backlash, Wendy’s later claimed in a statement that its CEO’s comments about dynamic pricing during the earnings call was “misconstrued.”

“This was misconstrued in some media reports as an intent to raise prices when demand is highest at our restaurants,” reads the statement. “We have no plans to do that and would not raise prices when our customers are visiting us most.”

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic covid-19 testing ukInternational

How nature can alter our sense of time

Time pressure is bad for your health- but the answer may be right outside your door.

Do you ever get that feeling that there aren’t enough hours in the day? That time is somehow racing away from you, and it is impossible to fit everything in. But then, you step outside into the countryside and suddenly everything seems slower, more relaxed, like time has somehow changed.

It’s not just you - recent research showed nature can regulate our sense of time.

For many of us, the combined demands of work, home and family mean that we are always feeling like we don’t have enough time. Time poverty has also been exacerbated by digital technologies. Permanent connectivity extends working hours and can make it difficult to switch off from the demands of friends and family.

Recent research suggests that the antidote to our lack of time may lie in the natural world. Psychologist Richardo Correia, at the University of Turku in Finland, found that being in nature may change how we experience time and, perhaps, even give us the sense of time abundance.

Correia examined research which compared people’s experiences of time when they performed different types of tasks in urban and natural environments. These studies consistently showed that people report a sense of expanded time when they were in nature compared to when they were in an urban environment.

For example, people are more likely to perceive a walk in the countryside as longer than a walk of the same length in the city. Similarly, people report perceiving time as passing more slowly while performing tasks in natural green environments than in urban environments. Nature seems to slow and expand our sense of time.

It’s not just our sense of time in the moment which appears to be altered by the natural world, it’s also our sense of the past and future. Previous research shows that spending time in nature helps to shift our focus from the immediate moment towards our future needs. So rather than focusing on the stress of the demands on our time, nature helps us to see the bigger picture.

This can help us to prioritise our actions so that we meet our long-term goals rather than living in a perpetual state of “just about keeping our head above water”.

This is in part because spending time in nature appears to make us less impulsive, enabling us to delay instant gratification in favour of long-term rewards.

Why does nature affect our sense of time?

Spending time in nature is known to have many benefits for health and wellbeing. Having access to natural spaces such as beaches, parks and woodlands is associated with reduced anxiety and depression, improved sleep, reduced levels of obesity and cardiovascular disease, and improved wellbeing.

Some of these benefits may explain why being in nature alters our experience of time.

The way we experience time is shaped by our internal biological state and the events going on in the world around us. As a result, emotions such as stress, anxiety and fear can distort our sense of the passage of time.

The relaxing effect of natural environments may counter stress and anxiety, resulting in a more stable experience of time. Indeed, the absence of access to nature during COVID-19 may help to explain why people’s sense of time became so distorted during the pandemic lockdowns.

In the short term, being away from the demands of modern day life may provide the respite needed to re-prioritise life, and reduce time pressure by focusing on what actually needs to be done. In the longer term, time in nature may help to enhance our memory and attention capacity, making us better able to deal with the demands on our time.

Accessing nature

Getting out into nature may sound like a simple fix, but for many people, particularly those living in urban areas, nature can be hard to access. Green infrastructure such as trees, woodlands, parks and allotments in and around towns and cities are essential to making sure the benefits of time in nature are accessible to everyone.

If spending time in nature isn’t possible for you, there are other ways that you can regain control of your time. Start by closely examining how you use time throughout your week. Auditing your time can help you see where time is being wasted and to identify action to help you to free up more time in your life.

Alternatively, try to set yourself some boundaries in how you use time. This could be limiting when you access emails and social media, or it could be booking in time in your calendar to take a break. Taking control of your time and how you use it can help to you overcome the sense that time is running away from you.

Ruth Ogden receives funding from The British Academy, The Wellcome Trust, the Economic and Social Research Council, CHANSE and Horizon 2020. This piece was written as part of the ESRC grant project “TIMED: TIMe experience in Europe’s Digital age" (ES/X005321/1) supported by CHANSE and the British Academy project "The Times of a Just Transition" (GCPS2100005).

Jessica Thompson is the CEO for City of Trees, a Manchester (UK) based community forestry charity and is involed in academic research to better understand the impacts of civic environmental activity through an academic lens.

depression pandemic covid-19 europe ukInternational

Never Ever Forget

Never Ever Forget

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via DailyReckoning.com,

Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare quotes the soothsayer’s warning…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via DailyReckoning.com,

Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare quotes the soothsayer’s warning Julius Caesar about what turned out to be an impending assassination on March 15.

The death of American liberty happened around the same time four years ago, when the orders went out from all levels of government to close all indoor and outdoor venues where people gather.

It was not quite a law and it was never voted on by anyone. Seemingly out of nowhere, people who the public had largely ignored, the public health bureaucrats, all united to tell the executives in charge — mayors, governors and the president — that the only way to deal with a respiratory virus was to scrap freedom and the Bill of Rights.

What Happened to This Document?

In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a classified document, only to be released to the public months later. The document initiated the lockdowns. It still does not exist on any government website.

The White House Coronavirus Response Task Force, led by the vice president, will coordinate a whole-of-government approach, including governors, state and local officials, and members of Congress, to develop the best options for the safety, well-being and health of the American people. HHS is the LFA [lead federal agency] for coordinating the federal response to COVID-19.

Closures were guaranteed:

Recommend significantly limiting public gatherings and cancellation of almost all sporting events, performances and public and private meetings that cannot be convened by phone. Consider school closures. Issue widespread “stay at home” directives for public and private organizations, with nearly 100% telework for some, although critical public services and infrastructure may need to retain skeleton crews. Law enforcement could shift to focus more on crime prevention, as routine monitoring of storefronts could be important.

A Blueprint for Totalitarian Control of Society

In this vision of turnkey totalitarian control of society, the vaccine was pre-approved: “Partner with pharmaceutical industry to produce anti-virals and vaccine.”

The National Security Council was put in charge of policymaking. The CDC was just the marketing operation. That’s why it felt like martial law. Without using those words, that’s what was being declared. It even urged information management, with censorship strongly implied.

As part of the lockdowns, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which was and is part of the Department of Homeland Security, as set up in 2018, broke the entire American labor force into essential and nonessential.

They also set up and enforced censorship protocols, which is why it seemed like so few objected. In addition, CISA was tasked with overseeing mail-in ballots for the November election.

Congress passed and the president signed the 880-page CARES Act, which authorized the distribution of $2 trillion to states, businesses and individuals, thus guaranteeing that lockdowns would continue for the duration.

They wanted zero cases of COVID in the country. That was never going to happen. It’s very likely that the virus had already been circulating in the U.S. and Canada from October 2019. A famous study by Jay Bhattacharya came out in May 2020 discerning that infections and immunity were already widespread in the California county they examined.

What that implied was two crucial points: There was zero hope for the zero COVID mission and this pandemic would end as they all did, through herd immunity, not from a vaccine as such. That was certainly not the message that was being broadcast from Washington.

The growing sense at the time was that we all had to sit tight and just wait for the inoculation on which pharmaceutical companies were working.

Different Sets of Rules

By summer 2020, you recall what happened. A restless generation of kids fed up with this stay-at-home nonsense seized on the opportunity to protest racial injustice in the killing of George Floyd.

Public health officials approved of these gatherings — unlike protests against lockdowns — on grounds that racism was a virus even more serious than COVID. Some of these protests got out of hand and became violent and destructive.

Meanwhile, substance abuse raged — the liquor and weed stores never closed — and immune systems were being degraded by lack of normal exposure, exactly as some doctors had predicted.

Millions of small businesses had closed. The learning losses from school closures were mounting, as it turned out that Zoom school was near worthless.

It was about this time that Trump seemed to figure out that he had been played and started urging states to reopen. But it was strange: He seemed to be less in the position of being a president in charge and more of a public pundit, tweeting out his wishes until his account was banned. He was unable to put the worms back in the can that he had approved opening.

By that time, and by all accounts, Trump was convinced that the whole effort was a mistake, that he had been trolled into wrecking the country he promised to make great. It was too late.

Mail-in ballots had been widely approved, the country was in shambles, the media and public health bureaucrats were ruling the airwaves and his final months of the campaign failed even to come to grips with the reality on the ground.

(In this interview, I discuss how the censorship industrial complex is working to end free speech in America. I also discuss what I see coming in the November election. Go here to watch it).

Didn’t They Say Vaccines Would Prevent Infection?

At the time, many people had predicted that once Biden took office and the vaccine was released, COVID would be declared to have been beaten. But that didn’t happen and mainly for one reason: Resistance to the vaccine was more intense than anyone had predicted.

The Biden administration attempted to impose mandates on the entire U.S. workforce. Thanks to a Supreme Court ruling, that effort was thwarted but not before HR departments around the country had already implemented them.

As the months rolled on — and four major cities closed all public accommodations to the unvaccinated, who were being demonized for prolonging the pandemic — it became clear that the vaccine could not and would not stop infection or transmission, which means that this shot could not be classified as a public health benefit.

Even as a private benefit, the evidence was mixed. Any protection it provided was short-lived and reports of vaccine injury began to mount. Even now, we cannot gain full clarity on the scale of the problem because essential data and documentation remain classified.

What Exactly Happened?

After four years, we find ourselves in a strange position. We still do not know precisely what unfolded in mid-March 2020: who made what decisions, when, and why. There has been no serious attempt at any high level to provide a clear accounting much less assign blame.

Not even Tucker Carlson, who reportedly played a crucial role in getting Trump to panic over the virus, will tell us the source of his own information or what his source told him. There have been a series of valuable hearings in the House and Senate but they have received little to no press attention, and none has focused on the lockdown orders themselves.

The prevailing attitude in public life is just to forget the whole thing. And yet we live now in a country very different from the one we inhabited five years ago. Our media is captured. Social media is widely censored in violation of the First Amendment, a problem being taken up by the Supreme Court this month with no certainty of the outcome.

The administrative state that seized control has not given up power. Crime has been normalized. Art and music institutions are on the rocks. Public trust in all official institutions is at rock bottom. We don’t even know if we can trust the elections anymore.

In the early days of lockdown, Henry Kissinger warned that if the mitigation plan does not go well, the world will find itself set “on fire.” He died in 2023. Meanwhile, the world is indeed on fire.

The essential struggle in every country on Earth today concerns the battle between the authority and power of the permanent administration apparatus of the state - the very one that took total control in lockdowns - and the enlightenment ideal of a government that is responsible to the will of the people and the moral demand for freedom and rights.

How this struggle turns out is the essential story of our times.

-

Spread & Containment2 weeks ago

Spread & Containment2 weeks agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoParexel CEO to retire; CAR-T maker AffyImmune promotes business leader to chief executive

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoKey Events This Week: All Eyes On Core PCE Amid Deluge Of Fed Speakers

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoA Blue State Exodus: Who Can Afford To Be A Liberal