Smart containment and mitigation measures to confront the COVID-19 pandemic: Tailoring the pandemic response to the realities of poor and developing countries

Smart containment and mitigation measures to confront the COVID-19 pandemic: Tailoring the pandemic response to the realities of poor and developing countries

In the World Development Report 2014 - Risk and Opportunity, we put a spotlight on pandemics. There, we warned that most countries and the international community were unprepared for a risk of this nature. The world is four months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is now clear that we are facing an acute public health, economic, and humanitarian crisis. What makes managing this health emergency so challenging is that if unattended, it could lead to countless numbers of fatalities—yet if drastic measures to contain the spread of the virus are imposed, it can produce a deep recession with business closures, mass unemployment, and poverty. As The Economist writes, “the trade-off between saving lives and saving livelihoods is excruciating” (March 26, 2020).

However, as Francisco Ferreira reminds us in a recent blogpost, this “trade-off is real—but its terms are not fixed in stone.” The objective of public policy in the face of the pandemic should be easing this trade-off: reducing the fatalities from COVID-19 while preserving people’s livelihoods.

In advanced countries, the lives-versus-livelihoods trade-off can be eased with immense resources. For example, the United States will spend around US$5,700 per capita to tackle the crisis, while Denmark will spend about US$7,500 per capita. Poor and developing countries face a very different situation: short of money and low in government capacity, they carry the burden of precarious health systems, overcrowded cities, and informal labor markets.

This dire situation calls for pragmatic and effective solutions, tailored to the reality of poor and developing countries. Broadly speaking, public policy approaches to face the pandemic can be divided into two categories: 1) relief and recovery economic policies; and 2) containment and mitigation public health measures. I will address the first category only briefly here: relief and recovery measures should include a set of policies to increase public health care capacity (procuring emergency hospital space, breathing ventilators, medical protective equipment, and testing kits); protect the poor and vulnerable (scaling up both targeted and untargeted cash transfers); provide temporary support to affected businesses (granting subsidies and tax reductions); and ensure the continuity of public services. (For more on economic policy see, for instance, Berk Özler’s blogpost on social protection and my article with Steven Pennings on macroeconomic policy). I will devote the rest of this blogpost to containment and mitigation measures.

In the 2014 World Development Report, we propose some principles for effective risk management that form the basis for the recommendations that follow. The first is that preparation is the key to resilience, even during a crisis. The second is that coping with adverse systemic shocks requires a whole-of-government, whole-of-society integrated response. The third is that public actions should consider the realities of each country, making sure that the unintended costs do not outweigh the potential benefits.

With poor and developing countries in mind, let me share some thoughts on what not to do and what to do regarding containment and mitigation measures.

The Problems with Lockdowns

I have serious doubts about the efficacy of lockdowns. I recognize that governments have had difficult choices to make on the best approach for their countries to contain the spread of the disease. Surrounded by uncertainty as to the threat of the virus and the prevalence of the infection in their countries, some governments chose lockdowns. With the benefit of more evidence and time, I believe we can make better choices.

Using clear-headed cost-benefit analysis, Julian Jamison concludes that “We should practice sustained yet moderate social distancing—but not a lockdown” (The Incidental Economist, April 1, 2020). Jamison’s conclusion applies to advanced economies, but they are even more relevant to poor and developing countries where lockdowns tend to be indiscriminate and disorganized. In Ideas for India, Debraj Ray and S. Subramanian argue against a comprehensive lockdown and in favor of a “reasonable alternative” whereby young adults are allowed to work and the elderly are insulated and cared for in their own households. Such measures can be guided by antibody testing when possible (March 28, 2020).

Let me summarize why I think lockdowns are ineffective and excessively costly, especially in developing countries.

Lockdowns are ineffective in containing the spread of the disease when:

- They are imposed in cities with pervasive overcrowded dwellings and neighborhoods. There, instead of social distancing, the result from a lockdown is social compression: “Confining people in cities such as Lagos, Mumbai, or Manila where half of the population may live in slums, will force them to be crammed in a room with six or eight people without easy access to water or soap” (The Financial Times, April 2, 2020).

- They produce massive displacement of people, especially from urban to rural areas, spreading, rather than containing, the contagion of the virus. This is happening in India and Kenya, for instance, where migrant workers who depend on daily labor are escaping cities in lockdown in massive numbers and returning to their hometowns (NPR, March 31, 2020).

And lockdowns are excessively costly in economic and human terms because:

- They can lead to mass unemployment and bankruptcies. Most developing-country governments do not have the means to support people and businesses in a deep recession. They have large levels of external debt, low tax revenues, and high credit risk—a situation worsened by the pandemic-related drop in commodity prices (Research & Policy Briefs, March 26, 2020).

- They can put the families of informal workers, especially daily laborers, at the risk of starvation, crime, and disease. From South Asia to Africa to Latin America, hundreds of millions of informal workers, without unemployment insurance, paid leave, or savings, would rather work and face the risk of infection than starve (The Wall Street Journal, April 2, 2020).

- They may create the conditions for unbridled domestic violence. Being in close quarters with an abusive spouse or parent is dreadful. It can be even worse when police protection is unavailable as police resources are diverted to enforcing the lockdown. In Hubei province in China, the initial epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, official reports of domestic violence tripled during the quarantine. “Women and children who live with domestic violence have no escape from their abusers during quarantine, and from Brazil to Germany, Italy to China, activists and survivors say they are already seeing an alarming rise in abuse” (The Guardian, March 28, 2020).

- They can be manipulated to suppress political opposition and legitimate social unrest in authoritarian and dictatorial regimes. In several countries, governments have declared states of emergency and deployed the armed forces: “The greater worries lie elsewhere, in the abuse of office and the threats to freedom. Some politicians are already making power grabs…” (The Economist, March 26, 2020).

- The opportunity cost of the loss of public and private resources due to lockdowns is immense in poor and developing countries. This loss implies, for instance, a diminished ability to provide other vital services in health care, education, and safety. This, added to the loss of jobs and income, can significantly worsen poverty and vulnerability (World Bank EAP Update 2020).

Worse than a lockdown is a series of repeated and uncertain lockdowns. The risk of second and third waves of infection is large in populations with low immunity. The prospect of repeated and uncertain lockdowns can devastate the economy and worsen human suffering beyond comprehension. Whether or not they have tried lockdowns as a first line of defense, countries around the world, especially poor and developing countries, should turn instead to sustainable smart containment and mitigation measures.

Smart Containment and Mitigation Measures

Although there is much uncertainty regarding the science around COVID-19, including its epidemiology, there is some evidence that can help guide smart containment and mitigation measures. (For the evidence, see Center for Disease Control 2020; and for a summary of health infrastructure for containment, see Box I.B.5 in World Bank EAP Update 2020). Smart containment and mitigation measures are especially relevant where lockdowns are ineffective and excessively costly. They are also important for countries that are considering sensible exit strategies from their lockdowns to prevent a second wave of infection (see Piero Ghezzi´s “Ideas for an Exit Strategy”). Some of these actions may seem simple, but they are not always easy to implement in poor-country contexts.

-

Practice effective personal and public hygiene. Thoroughly washing hands with soap and water or using a hand sanitizer that is strong enough is a powerful defense. Yet, in many poor countries, people don’t have access to water (2.2 billion people, according to WHO 2019) and cannot afford to buy enough soap and sanitizer. Consider the following recommendations:

- Conduct massive, imaginative, and persuasive public campaigns for people to wash and clean their hands properly.

- Install public hand-washing stations where water is scarce. This was done in West Africa during the Ebola crisis, installing simple devices (two buckets and some chlorine) in public buildings and schools (NPR, March 30, 2020).

- Install and maintain sanitizer dispensers in public places, such as schools, public transport, restaurants, banks, and shops.

- Disinfect public places frequently and extensively.

-

Protect the most vulnerable to the disease. The elderly (and people with certain underlying health conditions) seem to be the most vulnerable to COVID-19. In theory, we would want to insulate the elderly while enabling the young to keep the economy going. In practice, cocooning the elderly may be a high-risk and socially unacceptable strategy. However, some forms of less drastic insulation may be feasible. (Look for a forthcoming piece by Adam Wagstaff on protecting the elderly.) Consider the following recommendations:

- Household-level shielding for the elderly (and possible other vulnerable people). Incentives can be provided for the elderly to stay at home and their family members to practice safe behaviors around them. Dahab et al. (2020) offer some general principles and practical procedures to shield high-risk populations. The government can help by providing information to the families and cash transfers to the elderly as support and incentive for suitable behavior.

- Social shelters for the elderly. This can be designed for families that cannot provide for the safety or the insulation of their elderly relatives. Providing these shelters is a challenging task for any government, especially for those with low capacity. The international community, including charitable organizations, could help with this responsibility. Ideally, these shelters should be run by people who have acquired immunity to the coronavirus (which, of course, implies antibody testing).

-

Isolate people who are currently infected. Targeting, tracing, and monitoring those who are currently infected and those who may have been exposed to the coronavirus are best practices that have allowed South Korea and Japan to control the outbreak while avoiding lockdowns (The Economist, April 3, 2020; and ). Proper testing is needed to make targeting, monitoring, and case tracing feasible (see point 4). While testing is procured, other complementary measures can be implemented. Consider the following recommendations,

- Self-quarantine. With the information provided by antigen testing, residents and international travelers can be ordered to self-quarantine. In some cases, it may be necessary for the government to provide the incentive and support of a cash transfer.

- Social-quarantine. If household conditions are not propitious for self-quarantine, the government can consider providing sheltering facilities for people who are infected but are not in need of critical medical care. They would also get a cash transfer, possibly to help support their families. Ideally, these places for social-quarantine would be run by people who have acquired immunity to the coronavirus.

- Employ digital data. Enforcing self- and social-quarantine can be facilitated by the use of digital data devices, such as mobile phone apps. They can also help in tracing contacts and in providing information on coronavirus hotspots.

- Require face masks in public. The government can procure large supplies of masks, distribute them for free, and make their use mandatory in certain public places, such as public transport, shops, and markets. This is important because a large portion of individuals carrying the coronavirus are asymptomatic. Since the primary purpose of wearing masks is protecting others, social enforcement can make this practice feasible and prevalent. After initial reluctance, the US Center for Disease Control now “recommends wearing cloth face coverings in public settings where other social distancing measures are difficult to maintain (e.g., grocery stores and pharmacies)”; and some countries in Europe, including Austria, have made this practice mandatory (Financial Times, April 2, 2010).

-

Test, test, test. Mass testing for the coronavirus is an indispensable piece of information for smart containment and mitigation strategies. (Look for a forthcoming piece by World Bank economists Damien de Walque, Jed Friedman, and Aaditya Mattoo on COVID-19 testing.) The antigen test signals who is currently infected by the coronavirus and is likely contagious to others. The antibody test indicates who has been exposed to the coronavirus in the past and is likely to have developed immunity to it. Reliable, rapid, and scalable tests are currently being developed, with promising signals. Right now, the bottleneck for mass antigen and antibody testing is technological in advanced countries. Once this bottleneck is resolved, the challenge for developing countries will be large-scale implementation. De Walque, Friedman, and Mattoo recommend starting with targeted testing in the near term and, as capacity expands, scaling up testing to comprehensive levels. Consider the following recommendations:

- Antigen testing. Apply the antigen test to susceptible groups to determine who should be quarantined, who should be traced for potential infection (contact tracing), and what areas could be treated to prevent contagion hotspots. Since this test is available, obtain antigen testing kits from international companies and agencies. International organizations and aid agencies could provide knowledge, materials, and funding to obtain them.

- Antibody testing. When this becomes available, apply the antibody test first in a representative sample to determine the acquired immunity profile of the population (by area, age, gender, and other salient characteristics) and whether or not “herd” immunity is likely to have built up (The Economist, March 2, 2020). Then, scale up the test to obtain individual information to guide decisions on work and employment, access to public services, and contact with vulnerable groups. Enlist the help of international organizations to deploy and implement the test.

- Implementation capacity. Prepare and improve the implementation capacity of the public health care system to administer the new antigen and antibody tests, as soon as they are developed. This can involve enlisting the help of medical students and other university students, for instance.

The benefits of smart containment and mitigation efforts can be substantial. In their theoretical study of the macroeconomics of epidemics, Eichenbaum, Rebelo, and Trabandt (2020) analyze the gains of conditioning containment policies on people’s health status, so that infected people would not work, susceptible people would work but less than they normally do, and recovered people would work more. This “smart” containment policy significantly eases the lives-versus-livelihoods trade-off: it decreases the infection rate to less than half and the severity of the recession by more than 5 percentage points.

In practice, to approach and improve over this scenario, we need the knowledge that infection and immunity tests can provide, the ability to isolate people who are infected, the capacity to shield vulnerable populations, and a set of reasonable measures to diminish contagion. While the gains of smart containment and mitigation measures could be large in advanced countries, for developing countries they could literally be a matter of life and death.

For ideas and suggestions, I am very grateful to Susmita Dasgupta, Damien del Walque, Sharmila Devadas, Jed Friedman, Piero Ghezzi, Olga Jonas, Aart Kraay, David Mackenzie, Aaditya Mattoo, Berk Özler, Steven Pennings, Firas Raad, Nurlina Shaharuddin, Mike Toman, and Adam Wagstaff. They are, however, not responsible for the opinions expressed in this note, and neither are the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.

Spread & Containment

The Coming Of The Police State In America

The Coming Of The Police State In America

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

The National Guard and the State Police are now…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

The National Guard and the State Police are now patrolling the New York City subway system in an attempt to do something about the explosion of crime. As part of this, there are bag checks and new surveillance of all passengers. No legislation, no debate, just an edict from the mayor.

Many citizens who rely on this system for transportation might welcome this. It’s a city of strict gun control, and no one knows for sure if they have the right to defend themselves. Merchants have been harassed and even arrested for trying to stop looting and pillaging in their own shops.

The message has been sent: Only the police can do this job. Whether they do it or not is another matter.

Things on the subway system have gotten crazy. If you know it well, you can manage to travel safely, but visitors to the city who take the wrong train at the wrong time are taking grave risks.

In actual fact, it’s guaranteed that this will only end in confiscating knives and other things that people carry in order to protect themselves while leaving the actual criminals even more free to prey on citizens.

The law-abiding will suffer and the criminals will grow more numerous. It will not end well.

When you step back from the details, what we have is the dawning of a genuine police state in the United States. It only starts in New York City. Where is the Guard going to be deployed next? Anywhere is possible.

If the crime is bad enough, citizens will welcome it. It must have been this way in most times and places that when the police state arrives, the people cheer.

We will all have our own stories of how this came to be. Some might begin with the passage of the Patriot Act and the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security in 2001. Some will focus on gun control and the taking away of citizens’ rights to defend themselves.

My own version of events is closer in time. It began four years ago this month with lockdowns. That’s what shattered the capacity of civil society to function in the United States. Everything that has happened since follows like one domino tumbling after another.

It goes like this:

1) lockdown,

2) loss of moral compass and spreading of loneliness and nihilism,

3) rioting resulting from citizen frustration, 4) police absent because of ideological hectoring,

5) a rise in uncontrolled immigration/refugees,

6) an epidemic of ill health from substance abuse and otherwise,

7) businesses flee the city

8) cities fall into decay, and that results in

9) more surveillance and police state.

The 10th stage is the sacking of liberty and civilization itself.

It doesn’t fall out this way at every point in history, but this seems like a solid outline of what happened in this case. Four years is a very short period of time to see all of this unfold. But it is a fact that New York City was more-or-less civilized only four years ago. No one could have predicted that it would come to this so quickly.

But once the lockdowns happened, all bets were off. Here we had a policy that most directly trampled on all freedoms that we had taken for granted. Schools, businesses, and churches were slammed shut, with various levels of enforcement. The entire workforce was divided between essential and nonessential, and there was widespread confusion about who precisely was in charge of designating and enforcing this.

It felt like martial law at the time, as if all normal civilian law had been displaced by something else. That something had to do with public health, but there was clearly more going on, because suddenly our social media posts were censored and we were being asked to do things that made no sense, such as mask up for a virus that evaded mask protection and walk in only one direction in grocery aisles.

Vast amounts of the white-collar workforce stayed home—and their kids, too—until it became too much to bear. The city became a ghost town. Most U.S. cities were the same.

As the months of disaster rolled on, the captives were let out of their houses for the summer in order to protest racism but no other reason. As a way of excusing this, the same public health authorities said that racism was a virus as bad as COVID-19, so therefore it was permitted.

The protests had turned to riots in many cities, and the police were being defunded and discouraged to do anything about the problem. Citizens watched in horror as downtowns burned and drug-crazed freaks took over whole sections of cities. It was like every standard of decency had been zapped out of an entire swath of the population.

Meanwhile, large checks were arriving in people’s bank accounts, defying every normal economic expectation. How could people not be working and get their bank accounts more flush with cash than ever? There was a new law that didn’t even require that people pay rent. How weird was that? Even student loans didn’t need to be paid.

By the fall, recess from lockdown was over and everyone was told to go home again. But this time they had a job to do: They were supposed to vote. Not at the polling places, because going there would only spread germs, or so the media said. When the voting results finally came in, it was the absentee ballots that swung the election in favor of the opposition party that actually wanted more lockdowns and eventually pushed vaccine mandates on the whole population.

The new party in control took note of the large population movements out of cities and states that they controlled. This would have a large effect on voting patterns in the future. But they had a plan. They would open the borders to millions of people in the guise of caring for refugees. These new warm bodies would become voters in time and certainly count on the census when it came time to reapportion political power.

Meanwhile, the native population had begun to swim in ill health from substance abuse, widespread depression, and demoralization, plus vaccine injury. This increased dependency on the very institutions that had caused the problem in the first place: the medical/scientific establishment.

The rise of crime drove the small businesses out of the city. They had barely survived the lockdowns, but they certainly could not survive the crime epidemic. This undermined the tax base of the city and allowed the criminals to take further control.

The same cities became sanctuaries for the waves of migrants sacking the country, and partisan mayors actually used tax dollars to house these invaders in high-end hotels in the name of having compassion for the stranger. Citizens were pushed out to make way for rampaging migrant hordes, as incredible as this seems.

But with that, of course, crime rose ever further, inciting citizen anger and providing a pretext to bring in the police state in the form of the National Guard, now tasked with cracking down on crime in the transportation system.

What’s the next step? It’s probably already here: mass surveillance and censorship, plus ever-expanding police power. This will be accompanied by further population movements, as those with the means to do so flee the city and even the country and leave it for everyone else to suffer.

As I tell the story, all of this seems inevitable. It is not. It could have been stopped at any point. A wise and prudent political leadership could have admitted the error from the beginning and called on the country to rediscover freedom, decency, and the difference between right and wrong. But ego and pride stopped that from happening, and we are left with the consequences.

The government grows ever bigger and civil society ever less capable of managing itself in large urban centers. Disaster is unfolding in real time, mitigated only by a rising stock market and a financial system that has yet to fall apart completely.

Are we at the middle stages of total collapse, or at the point where the population and people in leadership positions wise up and decide to put an end to the downward slide? It’s hard to know. But this much we do know: There is a growing pocket of resistance out there that is fed up and refuses to sit by and watch this great country be sacked and taken over by everything it was set up to prevent.

Government

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate…

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate iron levels in their blood due to a COVID-19 infection could be at greater risk of long COVID.

A new study indicates that problems with iron levels in the bloodstream likely trigger chronic inflammation and other conditions associated with the post-COVID phenomenon. The findings, published on March 1 in Nature Immunology, could offer new ways to treat or prevent the condition.

Long COVID Patients Have Low Iron Levels

Researchers at the University of Cambridge pinpointed low iron as a potential link to long-COVID symptoms thanks to a study they initiated shortly after the start of the pandemic. They recruited people who tested positive for the virus to provide blood samples for analysis over a year, which allowed the researchers to look for post-infection changes in the blood. The researchers looked at 214 samples and found that 45 percent of patients reported symptoms of long COVID that lasted between three and 10 months.

In analyzing the blood samples, the research team noticed that people experiencing long COVID had low iron levels, contributing to anemia and low red blood cell production, just two weeks after they were diagnosed with COVID-19. This was true for patients regardless of age, sex, or the initial severity of their infection.

According to one of the study co-authors, the removal of iron from the bloodstream is a natural process and defense mechanism of the body.

But it can jeopardize a person’s recovery.

“When the body has an infection, it responds by removing iron from the bloodstream. This protects us from potentially lethal bacteria that capture the iron in the bloodstream and grow rapidly. It’s an evolutionary response that redistributes iron in the body, and the blood plasma becomes an iron desert,” University of Oxford professor Hal Drakesmith said in a press release. “However, if this goes on for a long time, there is less iron for red blood cells, so oxygen is transported less efficiently affecting metabolism and energy production, and for white blood cells, which need iron to work properly. The protective mechanism ends up becoming a problem.”

The research team believes that consistently low iron levels could explain why individuals with long COVID continue to experience fatigue and difficulty exercising. As such, the researchers suggested iron supplementation to help regulate and prevent the often debilitating symptoms associated with long COVID.

“It isn’t necessarily the case that individuals don’t have enough iron in their body, it’s just that it’s trapped in the wrong place,” Aimee Hanson, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge who worked on the study, said in the press release. “What we need is a way to remobilize the iron and pull it back into the bloodstream, where it becomes more useful to the red blood cells.”

The research team pointed out that iron supplementation isn’t always straightforward. Achieving the right level of iron varies from person to person. Too much iron can cause stomach issues, ranging from constipation, nausea, and abdominal pain to gastritis and gastric lesions.

1 in 5 Still Affected by Long COVID

COVID-19 has affected nearly 40 percent of Americans, with one in five of those still suffering from symptoms of long COVID, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Long COVID is marked by health issues that continue at least four weeks after an individual was initially diagnosed with COVID-19. Symptoms can last for days, weeks, months, or years and may include fatigue, cough or chest pain, headache, brain fog, depression or anxiety, digestive issues, and joint or muscle pain.

Uncategorized

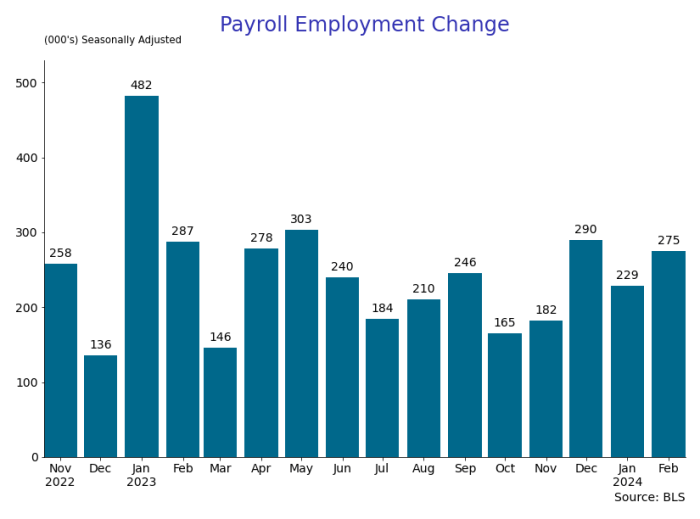

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemployment-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges

Join the Conversation