Government

Redefining Poverty: Towards a Transpartisan Approach

A new report from the National Academies of Science,

Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), An Updated Measure of

Poverty: (Re)Drawing the Line, has hit…

A new report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), An Updated Measure of Poverty: (Re)Drawing the Line, has hit Washington with something of a splash. Its proposals deserve a warm welcome across the political spectrum. Unfortunately, they are not always getting it from the conservative side of the aisle.

The AEI’s Kevin Corinth sees the NASEM proposals as a path to adding billions of dollars to federal spending. Congressional testimony by economist Bruce Meyer takes NASEM to task for outright partisan bias. Yet in their more analytical writing, these and other conservative critics offer many of the same criticisms of the obsolete methods that constitute the current approach to measuring poverty. As I will explain below, many of their recommendations for improvements are in harmony with the NASEM report. Examples include the need for better treatment of healthcare costs, the inclusion of in-kind benefits in resource measures, and greater use of administrative data rather than surveys.

After some reading, I have come to think that the disconnect between the critics’ political negative reaction to the NASEM report and their accurate analysis of flaws in current poverty measures has less to do with the conceptual basis of the new proposals and more with the way they should be put to work. That comes more clearly into focus if we distinguish between what we might call the tracking and the treatment functions, or macro and micro functions, of poverty measurement.

The tracking function has an analytic focus. It is a matter of assessing how many people are poor at a given time and tracing how their number varies in response to changes in policies and economic conditions. The treatment function, in contrast, has an administrative focus. It sets a poverty threshold that can be used to determine who is eligible for specific government programs and what their benefits will be.

There are parallels in the tracking and treatment methods that were developed during the Covid-19 pandemic. By early in 2020, it was clear to public health officials that something big was happening, but slow and expensive testing made it hard to track how and where the SARS-CoV-2 virus was spreading. Later, as tests became faster and more accurate, tracking improved. Wastewater testing made it possible to track the spread of the virus to whole communities even before cases began to show up in hospitals. As time went by, improved testing methods also led to better treatment decisions at the micro level. For example, faster and more accurate home antigen tests enabled effective use of treatments like Paxlovid, which works best if taken soon after symptoms develop.

Poverty measurement, like testing for viruses, also plays essential roles in both tracking and treatment. For maximum effectiveness, what we need is a poverty measure that can be used at both the macro and micro level. The measures now in use are highly flawed in both applications. Both the NASEM report itself and the works of its critics offer useful ideas about where we need to go. The following sections will deal first with the tracking function, then with the treatment function, and then with what needs to be done to devise a poverty measure suitable for both uses.

The tracking function of poverty measurement

As a tracking tool, the purpose of any poverty measure is to improve understanding. Each proposed measure represents the answer to a specific question. To understand poverty fully – what it is, how it has changed, who is poor, and why – we need to ask lots of questions. At this macro level, it is misguided to look for the one best measure of poverty.

First some basics. All of the poverty measures discussed here consist of two elements, a threshold, or measure of needs, and a measure of resources available to meet those needs. The threshold is based on a basic bundle of goods and services considered essential for a minimum acceptable standard of living. The first step in deriving a threshold is to define the basic bundle and determine its cost. The basic bundle can be defined in absolute terms or relative to median standards of living. If absolute, the cost of the basic bundle can be adjusted from year to year to reflect inflation, and if relative, to reflect changes in the median. Once the cost of the basic bundle is established, poverty thresholds themselves may be adjusted to reflect the cost of essentials not explicitly listed in the basic bundle. Further adjustments in the thresholds may be developed to reflect household size and regional differences.

Similarly, a poverty measure can include a narrower or broader definition of resources. A narrow definition might consider only a household’s regular inflows of cash. A broader definition might include the cash-equivalent value of in-kind benefits, benefits provided through the tax system, withdrawals from retirement savings, and other sources of purchasing power.

Finally, a poverty measure needs to specify the economic unit to which it applies. In some cases, that may be an individual. In other cases, it may be a family (a group related by kinship, marriage, adoption, or other legal ties) or a household (a group of people who live together and share resources regardless of kinship or legal relationships). Putting it all together, an individual, family, or household is counted as poor if their available resources are less than the applicable poverty threshold.

The current official poverty measure (OPM), which dates from the early 1960s, includes very simple versions of each of these components. It defines the basic bundle in absolute terms as three times the cost of a “thrifty food plan” determined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It then converts that to a set of thresholds for family units that vary by family size, with special adjustments for higher cost of living in Alaska and Hawaii. The OPM defines resources as before-tax regular cash income, including wages, salaries, interest, and retirement income; cash benefits such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and Supplemental Security Income; and a few other items. Importantly, the OPM does not include tax credits or the cash-equivalent value of in-kind benefits in its resource measure.

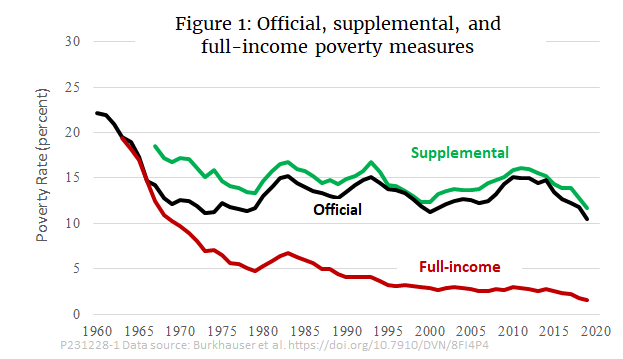

The parameters of the OPM were initially calibrated to produce a poverty rate for 1963 of approximately 20 percent. After that, annual inflation adjustments used the CPI-U, which to this day remains the most widely publicized price index. As nominal incomes rose due to economic growth and inflation, and as cash benefits increased, the share of the population living below the threshold fell. By the early 1970s, it had reached 12 percent. Since then, however, despite some cyclical ups and downs, it has changed little.

Today, nearly everyone views the OPM as functionally obsolete. Some see it as overstating the poverty rate, in that its measure of resources ignores in-kind benefits like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Others see it as understating poverty on the grounds that three times the cost of food is no longer enough to meet minimal needs for shelter, healthcare, childcare, transportation, and modern communication services. Almost no one sees the OPM as just right.

In a recent paper in the Journal of Political Economy, Richard V. Burkhauser, Kevin Corinth, James Elwell, and Jeff Larrimore provide an excellent overview of the overstatement perspective. The question they ask is what percentage of American households today lack the resources they need to reach the original three-times-food threshold. Simply put, was Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” on its own terms, a success or failure?

To answer that question, they develop what they call an absolute full-income poverty measure (FPM). Their first step in creating the FPM was to include more expense categories in the basic bundle, but calibrate it to make the FPM poverty rate for 1963 equal to the OPM rate for that year. Next, they expanded the resource measure to reflect the growth of in-kind transfer programs and the effects of taxes and tax credits. They also adopt the household, rather than the family, as their basic unit of analysis. Burkhauser et al. estimate that adding the full value of the EITC and other tax credits to resources, along with all in-kind transfer programs, cuts the poverty rate in 2019 to just 4 percent, far below the official 10.6 percent.

Going further, Burkhauser et al. raise the issue of the appropriate measure of the price level to be used in adjusting poverty thresholds over time. They note that many economists consider that the CPI-U overstates the rate of inflation, at least for the economy as a whole. Instead, they prefer the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index, which the Fed uses as a guide to monetary policy. Replacing the CPI-U with the PCE reduces the FPM poverty rate for 2019 to just 1.6 percent. It is worth noting, however, that some observers maintain that prices in the basket of goods purchased by poor households tend to rise at a faster rate than the average for all households. In that case, an FPM adjusted for inflation using the PCE would not fully satisfy one of the criteria set by Burkhauser et al., namely, that “the poverty measure should reflect the share of people who lack a minimum level of absolute resources.” (For further discussion of this point, see, e.g., this report to the Office of Management and Budget.)

Burkhauser et al. do not represent 1.6 percent as the “true” poverty rate. As they put it, although the FPM does point to “the near elimination of poverty based on standards from more than half a century ago,” they see that as “an important but insufficient indication of progress.” For a fuller understanding, measuring success or failure of Johnson’s War on Poverty is not enough. A poverty measure for today should give a better picture of the basic needs of today’s households and the resources available to them.

The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which the Census Bureau has published since 2011, is the best known attempt to modernize the official measure. The SPM enlarges the OPM’s basic bundle of essential goods to include not only food, but also shelter, utilities, telephone, and internet. It takes a relative approach, setting the threshold as a percentage of median expenditures and updating it not just for inflation, but also for the growth in real median household income. On the resource side, the SPM adds many cash and in-kind benefits, although not as many as the FPM. It further adjusts measured resources by deducting some necessary expenses, such as childcare and out-of-pocket healthcare costs. Finally, the SPM moves away from the family as its unit of analysis toward a household concept.

Since the SPM adds items to both thresholds and resources, it could, depending on its exact calibration, have a value either higher or lower than the OPM. In practice, as shown in Figure 1, it has tracked a little higher than the OPM. (For comparison, Burkhauser et al. calculate a variant of their FPM that uses a relative rather than an absolute poverty threshold. The relative FPM, not shown in Figure 1, tracks slightly higher than the SPM in most years.)

That brings us back to our starting point, the NASEM report. Its centerpiece is a recommended revision of the SPM that it calls the principal poverty measure (PPM). The PPM directly addresses several acknowledged shortcomings of the SPM. Some of the most important recommendations include:

- A further movement toward the household as the unit of analysis. To accomplish that, the PPM would place more emphasis on groups of people who live together and less on biological and legal relationships.

- A change in the treatment of healthcare costs. The SPM treats out-of-pocket healthcare spending as a deduction from resources but does not treat healthcare as a basic need. The PPM adds the cost of basic health insurance to its basic package of needs, adds the value of subsidized insurance (e.g., Medicaid or employer-provided) to its list of resources, and (like the SPM) deducts any remaining out-of-pocket healthcare spending from total resources.

- A change in the treatment of the costs of shelter that does a better job of distinguishing between the situation faced by renters and homeowners.

- Inclusion of childcare as a basic need and subsidies to childcare as a resource.

Although Burkhauser et al. do not directly address the PPM, judging by their criticisms of the SPM, it seems likely that they would regard nearly all of these changes as improvements. Many of the changes recommended in the NASEM report make the PPM more similar to the FPM than is the SPM.

Since the NASEM report makes recommendations regarding methodology for the PPM but does not calculate values, the PPM is not shown in Figure 1. In principle, because it modifies the way that both needs and resources are handled, the PPM could, depending on its exact calibration, produce poverty rates either above or below the SPM.

Measurement for treatment

The OPM, FPM, SPM, and PPM are just a few of the many poverty measures that economists have proposed over the years. When we confine our attention to tracking poverty, each of them adds to our understanding. When we turn to treatment, however, things become more difficult. A big part of the reason is that none of the above measures is really suitable for making micro-level decisions regarding the eligibility of particular households for specific programs.

For the OPM, that principle is laid out explicitly in U.S. Office of Management and Budget Statistical Policy Directive No. 14, first issued in 1969 and revised in 1978:

The poverty levels used by the Bureau of the Census were developed as rough statistical measures to record changes in the number of persons and families in poverty and their characteristics, over time. While they have relevance to a concept of poverty, these levels were not developed for administrative use in any specific program and nothing in this Directive should be construed as requiring that they should be applied for such a purpose.

Despite the directive, federal and state agencies do use the OPM, or measures derived from it, to determine eligibility for many programs, including Medicaid, SNAP, the Women, Infants, and Children nutrition program, Affordable Care Act premium subsidies, Medicare Part D low-income subsidies, Head Start, and the National School Lunch Program. The exact eligibility thresholds and the rules for calculating resources vary from program to program. The threshold at which eligibility ends or phase-out begins for a given household may be equal to the Census Bureau’s official poverty threshold, a fraction of that threshold, or a multiple of it. The resource measure may be regular cash income as defined by the OPM, or a modification based on various deductions and add-backs. Some programs include asset tests as well as income tests in their measures of resources. The exact rules for computing thresholds and resources vary not only from one program to another, but from state to state.

That brings us to what is, perhaps, the greatest source of alarm among conservative critics of the NASEM proposals. That is the concern that a new poverty measure such as the PPM would be used in a way that raised qualification thresholds while resource measures remained unchanged. It is easy to understand how doing so by administrative action could be seen as a backdoor way of greatly increasing welfare spending without proper legislative scrutiny.

Kevin Corinth articulates this fear in a recent working paper for the American Enterprise Institute. He notes that while the resource measures that agencies should use in screening applications are usually enshrined in statute, the poverty thresholds are not. If the Office of Management and Budget were to put its official stamp of approval on a new poverty measure such as the SPM or PPM, Corinth maintains that agencies would fall in line and recalculate their thresholds based on the new measure without making any change in the way they measure resources.

Corinth calculates that if the current OPM-based thresholds were replaced by new thresholds derived from the SPM, federal spending for SNAP and Medicaid alone would increase by $124 billion by 2033. No similar calculation can be made for the PPM, since it has not been finalized, but Corinth presumes that it, too, would greatly increase spending if it were used to recalculate thresholds while standards for resources remained unchanged.

Clearly, Corinth is onto a real problem. The whole conceptual basis of the SPM and PPM is to add relevant items in a balanced manner to both sides of the poverty equation, so that they more accurately reflect the balance between the cost of basic needs and the resources available to meet them. Changing one side of the equation while leaving the other untouched makes little sense.

Logically, then, what we need is an approach to poverty measurement that is both conceptually balanced and operationally suitable for use at both the macro and micro levels. Corinth himself acknowledges that at one point, when he notes that “changes could be made to both the SPM resource measure and SPM thresholds.” However, he does not follow up with specific recommendations for doing so. To fill the gap, I offer some ideas of my own in the next section.

Toward a balanced approach to micro-level poverty measurement

To transform the PPM from a tracking tool into one suitable for determining individual households’ eligibility for specific public assistance programs would require several steps.

1. Finalize a package of basic needs. For the PPM, those would include food, clothing, telephone, internet, housing needs based on fair market rents, basic health insurance, and childcare. The NASEM report recommends calibrating costs based on a percentage of median expenditures, but conceptually, they could instead be set in absolute terms, either based on costs in a given year or averaged over a fixed period leading up to the date of implementation of the new approach.

2. Convert the package of needs into thresholds. Thresholds would vary according to the size and composition of the household unit. They could also vary geographically, although there is room for debate on how fine the calibration should be. Thresholds would be updated to reflect changes in the cost of living as measured by changes in median expenditures or (in the absolute version) changes in price levels.

3. Finalize a list of resources. These would include cash income plus noncash benefits that households can use to meet food, clothing, and telecommunication needs; plus childcare subsidies, health insurance benefits and subsidies, rent subsidies, and (for homeowners) imputed rental income; minus tax payments net of refundable tax credits; minus work expenses, nonpremium out-of-pocket medical expenses, homeowner costs if applicable, and child support paid to another household.

4. Centralize collection of data on resources. Determining eligibility of individual households for specific programs would require assembling data from many sources. It would be highly beneficial to centralize the reporting of total resources as much as possible, so that all resource data would be available from a central PPM database. The IRS could provide data on cash income other than public benefits (wages, salaries, interest, dividends, etc.) and payments made to households through refundable tax credits such as the EITC. The federal or state agencies that administer SNAP, Medicaid and other programs could provide household-by-household data directly to the PPM database. Employers could report the cash-equivalent value of employer-provided health benefits along with earnings and taxable benefits.

5. Devise a uniform format for reporting eligible deductions from resources. Individual households applying for benefits from specific programs would be responsible for reporting applicable deductions from resources, such as work expenses, out-of-pocket medical expenses, homeowner costs and so on. A uniform format should be developed for reporting those deductions along with uniform standards for documenting them so that the information could be submitted to multiple benefit programs without undue administrative burden.

6. Use net total resources as the basis for all program eligibility. Decisions on eligibility for individual programs should use net total resources, as determined by steps (4) and (5), to determine eligibility for individual programs.

7. Harmonization of program phase-outs. It would be possible to implement steps (1) through (6) without making major changes to the phase-in and phaseout rules for individual programs. However, once a household-by-household measure of net total resources became available, it would be highly desirable to use it to compute benefit phaseouts from all programs in a harmonized fashion. At present, for example, a household just above the poverty line might face a phaseout rate of 24 percent for SNAP and 21 percent for EITC, giving it an effective marginal tax rate of 45 percent, not counting other programs or income and payroll taxes. As explained in this previous commentary, such high effective marginal tax rates impose severe work disincentives, especially on families that are just making the transition from poverty to self-sufficiency. Replacing the phase-outs for individual programs with a single harmonized “tax” on total resources as computed by the PPM formula could significantly mitigate work disincentives.

Implementing all of these steps would clearly be a major administrative and legislative undertaking. However, the result would be a public assistance system that was ultimately simpler, less prone to error, and less administratively burdensome both for government agencies at all levels and for poor households.

Conclusion

In a recent commentary for the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, Michael Tanner points to the potentially far-reaching significance of proposed revisions to the way poverty is measured. “Congress should use this opportunity to debate even bigger questions,” he writes, such as “what is poverty, and how should policymakers measure it?” Ultimately, he continues, “attempts to develop a statistical measure of poverty venture beyond science, reflecting value judgments and biases. Such measures cannot explain everything about how the poor really live, how easily they can improve their situation, or how policymakers can best help them.”

The “beyond science” caveat is worth keeping in mind for all discussions of poverty measurement. A case in point is the issue of whether to use an absolute or relative approach in defining needs. It is not that one is right and the other wrong. Rather, they reflect fundamentally different philosophies as to what poverty is. For example, as noted earlier, Burkhauser et al. compute both absolute and relative versions of their full-income poverty measure. The absolute version is the right one for answering the historical question they pose about the success or failure of the original War on Poverty, but for purposes of policy today, the choice is not so clear. Some might see an absolute measure, when used in a micro context, as producing too many false negatives, that is, failures to help those truly in need. Others might see the relative approach as producing too many false positives, spending hard-earned taxpayer funds on people who could get by on their own if they made the effort. The choice is more a matter of values than of science.

The choice of a price index for adjusting poverty measures over time also involves values as well as science. Should the index be one based on average consumption patterns for all households, such as the PCE or chained CPI-U, or should it be a special index based on the consumption patterns of low-income households? Should the index be descriptive, that is, based on observed consumption patterns for the group in question? Or should it be prescriptive, that is, based on a subjective estimate of “basics needed to live and work in the modern economy” as is the approach taken by the ALICE Essentials Index?

In closing, I would like to call attention to four additional reasons why conservative critics of existing poverty policy should welcome the proposed PPM, even in its unfinished state, as a major step in the right direction.

The PPM is inherently less prone to error. Bruce Meyer is concerned that “the NAS[EM]-proposed changes to poverty measurement would produce a measure of poverty that does a worse job identifying the most disadvantaged, calling poor those who are better off and not including others suffering more deprivation.” In fact, many features of the PPM make it inherently less prone than either the OPM or the SPM to both false positives and false negatives. The most obvious is its move toward a full-income definition of resources. That avoids one of the most glaring flaws in the OPM, namely, the identification of families as poor who in fact receive sufficient resources in the form of in-kind transfers or tax credits. The PPM also addresses some of the flaws of the SPM that Meyer singles out in his testimony, most notably in the treatment of healthcare. Furthermore, by placing greater emphasis on administrative data sources and less on surveys, the PPM would mitigate underreporting of income and benefits, which Burkhauser et al. identify as a key weakness of the SPM. (See NASEM Recommendations 6.2 and 6.3).

The PPM offers a pathway toward consistency and standardization in poverty policy. In his critique of the PPM, Tanner suggests that “Congress should decouple program eligibility from any single poverty measure, and adopt a broader definition of poverty that examines the totality of the circumstances that low-income people face and their potential to rise above them.” I see that kind of decoupling as exactly the wrong approach. Our existing welfare system is already a clumsy accretion of mutually inconsistent means-tested programs – as many as 80 of them, by one count. It is massively wasteful and daunting to navigate. In large part that is precisely because each component represents a different view of the “totality of circumstances” of the poor as seen by different policymakers at different times. What we need is not decoupling, but standardization and consistency. The proposed system-wide redefinition of poverty offers a perfect opportunity to make real progress in that direction.

The PPM would be more family-friendly. One pro-family feature of the PPM is its recognition of childcare costs on both the needs and the resources sides of the poverty equation. In addition, by moving toward households (defined by resource-sharing) rather than families (defined by legal relationships), the PPM would mitigate the marriage penalties that are built into some of today’s OPM-based poverty programs.

Properly implemented, the PPM would be more work-friendly. As noted above, the benefit cliffs, disincentive deserts, and high effective marginal tax rates of existing OPM-based poverty programs create formidable work disincentives. Moving toward a harmonized phaseout system based on the PPM’s full-income approach to resources could greatly reduce work disincentives, especially for households just above the poverty line that are struggling to take the last steps toward self-sufficiency.

In short, it is wrong to view the proposed PPM as part of a progressive plot to raid the government budget for the benefit of the undeserving, as some conservative critics seem to have done. Rather, both conservatives and progressives should embrace the PPM as a promising step forward and direct their efforts toward making sure it is properly implemented.

Based on a version originally published by Niskanen Center.

subsidies economic growth pandemic covid-19 monetary policy fed irs congress treatment testing spread

International

EyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

Ramiro Ribeiro

After six years as head of clinical development at Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Ramiro Ribeiro is joining EyePoint Pharmaceuticals as CMO.

“The…

After six years as head of clinical development at Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Ramiro Ribeiro is joining EyePoint Pharmaceuticals as CMO.

“The retinal community is relatively small, so everybody knows each other,” Ribeiro told Endpoints News in an interview. “As soon as I started to talk about EyePoint, I got really good feedback from KOLs and physicians on its scientific standards and quality of work.”

Ribeiro kicked off his career as a clinician in Brazil, earning a doctorate in stem cell therapy for retinal diseases. He previously held roles at Alcon and Ophthotech Corporation, now known as Astellas’ M&A prize Iveric Bio.

At Apellis, Ribeiro oversaw the Phase III development, filing and approval of Syfovre, the first drug for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The complement C3 inhibitor went on to make $275 million in 2023 despite reports of a rare side effect that only emerged after commercialization.

Now, Ribeiro is hoping to replicate that success with EyePoint’s lead candidate, EYP-1901 for wet AMD, which is set to enter the Phase III LUGANO trial in the second half of the year after passing a Phase II test in December.

Ribeiro told Endpoints he was optimistic about the company’s intraocular sustained-delivery tech, which he said could help address treatment burden and compliance issues seen with injectables. He also has plans to expand the EyePoint team.

“My goal is not just execution of the Phase III study — of course that’s a priority — but also looking at the pipeline and which different assets we can bring in to leverage the strength of the team that we have,” Ribeiro said.

— Ayisha Sharma

Remco Steenbergen

Remco Steenbergen→ Sandoz CFO Colin Bond will retire on June 30 and board member Remco Steenbergen will replace him. Steenbergen, who will step down from the board when he takes over on July 1, had a 20-year career with Philips and has held the group CFO post at Deutsche Lufthansa since January 2021. Bond joined Sandoz nearly two years ago and is the former finance chief at Evotec and Vifor Pharma. Investors didn’t react warmly to Wednesday’s news as shares fell by almost 4%.

The Swiss generics and biosimilars company, which finally split from Novartis in October 2023, has also nominated FogPharma CEO Mathai Mammen to the board of directors. The ex-R&D chief at J&J will be joined by two other new faces, Swisscom chairman Michael Rechsteiner and former Unilever CFO Graeme Pitkethly.

On Monday, Sandoz said it completed its $70 million purchase of Coherus BioSciences’ Lucentis biosimilar Cimerli sooner than expected. The FDA then approved its first two biosimilars of Amgen’s denosumab the next day, in a move that could whittle away at the pharma giant’s market share for Prolia and Xgeva.

Sean Marett

Sean Marett→ BioNTech’s chief business and commercial officer Sean Marett will retire on July 1 and will have an advisory role “until the end of the year,” the German drugmaker said in a release. Legal chief James Ryan will assume CBO responsibilities and BioNTech plans to name a new chief commercial officer by the end of the month. Marett was hired as BioNTech’s COO in 2012 after gigs at GSK, Evotec and Next Pharma, and led its commercial efforts as the Pfizer-partnered Comirnaty received the first FDA approval for a Covid-19 vaccine. BioNTech has also built a cancer portfolio that TD Cowen’s Yaron Werber described as “one of the most extensive” in biotech, from antibody-drug conjugates to CAR-T therapies.

Chris Austin

Chris Austin→ GSK has plucked Chris Austin from Flagship and he’ll start his new gig as the pharma giant’s SVP, research technologies on April 1. After a long career at NIH in which he was director of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), Austin became CEO of Flagship’s Vesalius Therapeutics, which debuted with a $75 million Series A two years ago this week but made job cuts that affected 43% of its employees six months into the life of the company. In response to Austin’s departure, John Mendlein — who chairs the board at Sail Biomedicines and has board seats at a few other Flagship biotechs — will become chairman and interim CEO at Vesalius “later this month.”

→ BioMarin has lined up Cristin Hubbard to replace Jeff Ajer as chief commercial officer on May 20. Hubbard worked for new BioMarin chief Alexander Hardy as Genentech’s SVP, global product strategy, immunology, infectious diseases and ophthalmology, and they had been colleagues for years before Hardy was named Genentech CEO in 2019. She shifted to Roche Diagnostics as global head of partnering in 2021 and had been head of global product strategy for Roche’s pharmaceutical division since last May. Sales of the hemophilia A gene therapy Roctavian have fallen well short of expectations, but Hardy insisted in a recent investor call that BioMarin is “still very much at the early stage” in the launch.

Pilar de la Rocha

Pilar de la Rocha→ BeiGene has promoted Pilar de la Rocha to head of Europe, global clinical operations. After 13 years in a variety of roles at Novartis, de la Rocha was named global head of global clinical operations excellence at the Brukinsa maker in the summer of 2022. A short time ago, BeiGene ended its natural killer cell therapy alliance with Shoreline Biosciences, saying that it was “a result of BeiGene’s internal prioritization decisions and does not reflect any deficit in Shoreline’s platform technology.”

Andy Crockett

Andy Crockett→ Andy Crockett has resigned as CEO of KalVista Pharmaceuticals. Crockett had been running the company since its launch in 2011 and will hand the keys to president Ben Palleiko, who joined KalVista in 2016 as CFO. Serious safety issues ended a Phase II study of its hereditary angioedema drug KVD824, but KalVista is mounting a comeback with positive Phase III results for sebetralstat in the same indication and could compete with Takeda’s injectable Firazyr. “If approved, sebetralstat may offer a compelling treatment option for patients and their caregivers given the long-standing preference for an effective and safe oral therapy that provides rapid symptom relief for HAE attacks,” Crockett said last month.

Steven Lo

Steven Lo→ Vaxart has tapped Steven Lo as its permanent president and CEO, while interim chief Michael Finney will stay on as chairman. Endpoints News last caught up with Lo when he became CEO at Valitor, the UC Berkeley spinout that raised a $28 million Series B round in October 2022. The ex-Zosano Pharma CEO had a handful of roles in his 13 years at Genentech before his appointments as chief commercial officer of Corcept Therapeutics and Puma Biotechnology. Andrei Floroiu resigned as Vaxart’s CEO in mid-January.

Kartik Krishnan

Kartik Krishnan→ Kartik Krishnan has taken over for Martin Driscoll as CEO of OncoNano Medicine, and Melissa Paoloni has moved up to COO at the cancer biotech located in the Dallas-Fort Worth suburb of Southlake. The execs were colleagues at Arcus Biosciences, Gilead’s TIGIT partner: Krishnan spent two and a half years in the CMO post, while Paoloni was VP of corporate development and external alliances. In 2022, Krishnan took the CMO job at OncoNano and was just promoted to president and head of R&D last November. Paoloni came on board as OncoNano’s SVP, corporate development and strategy not long after Krishnan’s first promotion.

→ Genesis Research Group, a consultancy specializing in market access, has brought in David Miller as chairman and CEO, replacing co-founder Frank Corvino — who is transitioning to the role of vice chairman and senior advisor. Miller joins the New Jersey-based team with a number of roles under his belt from Biogen (SVP of global market access), Elan (VP of pharmacoeconomics) and GSK (VP of global health outcomes).

Adrian Schreyer

Adrian Schreyer→ Adrian Schreyer helped build Exscientia’s AI drug discovery platform from the ground up, but he has packed his bags for Nimbus Therapeutics’ AI partner Anagenex. The new chief technology officer joined Exscientia in 2013 as head of molecular informatics and was elevated to technology chief five years later. He then held the role of VP, AI technology until January, a month before Exscientia fired CEO Andrew Hopkins.

→ Paul O’Neill has been promoted from SVP to EVP, quality & operations, specialty brands at Mallinckrodt. Before his arrival at the Irish pharma in March 2023, O’Neill was executive director of biologics operations in the second half of his 12-year career with Merck driving supply strategy for Keytruda. Mallinckrodt’s specialty brands portfolio includes its controversial Acthar Gel (a treatment for flares in a number of chronic and autoimmune indications) and the hepatorenal syndrome med Terlivaz.

David Ford

David Ford→ Staying in Ireland, Prothena has enlisted David Ford as its first chief people officer. Ford worked in human resources at Sanofi from 2002-17 and then led the HR team at Intercept, which was sold to Italian pharma Alfasigma in late September. We recently told you that Daniel Welch, the former InterMune CEO who was a board member at Intercept for six years, will succeed Lars Ekman as Prothena’s chairman.

Ben Stephens

Ben Stephens→ Co-founded by Sanofi R&D chief Houman Ashrafian and backed by GSK, Eli Lilly partner Sitryx stapled an additional $39 million to its Series A last fall. It has now welcomed a pair of execs: Ben Stephens (COO) had been finance director for ViaNautis Bio and Rinri Therapeutics, and Gordon Dingwall (head of clinical operations) is a Roche and AstraZeneca vet who led development operations at Mission Therapeutics. Dingwall has also served as a clinical operations leader for Shionogi and Freeline Therapeutics.

Steve Alley

Steve Alley→ MBrace Therapeutics, an antibody-drug conjugate specialist that nabbed $85 million in Series B financing last November, has named Steve Alley as CSO. Alley spent two decades at Seagen before the $43 billion buyout by Pfizer and was the ADC maker’s executive director, translational sciences.

→ California cancer drug developer Apollomics, which has been mired in Nasdaq compliance problems nearly a year after it joined the public markets through a SPAC merger, has recruited Matthew Plunkett as CFO. Plunkett has held the same title at Nkarta as well as Imago BioSciences — leading the companies to $290 million and $155 million IPOs, respectively — and at Aeovian Pharmaceuticals since March 2022.

Heinrich Haas

Heinrich Haas→ Co-founded by Oxford professor Adrian Hill — the co-inventor of AstraZeneca’s Covid-19 vaccine — lipid nanoparticle biotech NeoVac has brought in Heinrich Haas as chief technology officer. During his nine years at BioNTech, Haas was VP of RNA formulation and drug delivery.

Kimberly Lee

Kimberly Lee→ New Jersey-based neuro biotech 4M Therapeutics is making its Peer Review debut by introducing Kimberly Lee as CBO. Lee was hired at Taysha Gene Therapies during its meteoric rise in 2020 and got promoted to chief corporate affairs officer in 2022. Earlier, she led corporate strategy and investor relations efforts for Lexicon Pharmaceuticals.

→ Another Peer Review newcomer, Osmol Therapeutics, has tapped former Exelixis clinical development chief Ron Weitzman as interim CMO. Weitzman only lasted seven months as medical chief of Tango Therapeutics after Marc Rudoltz had a similarly short stay in that position. Osmol is going after chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment with its lead asset OSM-0205.

→ Last August, cardiometabolic disease player NeuroBo Pharmaceuticals locked in Hyung Heon Kim as president and CEO. Now, the company is giving Marshall Woodworth the title of CFO and principal financial and accounting officer, after he served in the interim since last October. Before NeuroBo, Woodworth had a string of CFO roles at Nevakar, Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, Aerocrine and Fureix Pharmaceuticals.

Claire Poll

Claire Poll→ Claire Poll has retired after more than 17 years as Verona Pharma’s general counsel, and the company has appointed Andrew Fisher as her successor. In his own 17-year tenure at United Therapeutics that ended in 2018, Fisher was chief strategy officer and deputy general counsel. The FDA will decide on Verona’s non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis candidate ensifentrine by June 26.

Nancy Lurker

Nancy Lurker→ Alkermes won its proxy battle with Sarissa Capital Management and is tinkering with its board nearly nine months later. The newest director, Bristol Myers Squibb alum Nancy Lurker, ran EyePoint Pharmaceuticals from 2016-23 and still has a board seat there. For a brief period, Lurker was chief marketing officer for Novartis’ US subsidiary.

→ Chaired by former Celgene business development chief George Golumbeski, Shattuck Labs has expanded its board to nine members by bringing in ex-Seagen CEO Clay Siegall and Tempus CSO Kate Sasser. Siegall holds the top spots at Immunome and chairs the board at Tourmaline Bio, while Sasser came to Tempus from Genmab in 2022.

Scott Myers

Scott Myers→ Ex-AMAG Pharmaceuticals and Rainier Therapeutics chief Scott Myers has been named chairman of the board at Convergent Therapeutics, a radiopharma player that secured a $90 million Series A last May. Former Magenta exec Steve Mahoney replaced Myers as CEO of Viridian Therapeutics a few months ago.

→ Montreal-based Find Therapeutics has elected Tony Johnson to the board of directors. Johnson is in his first year as CEO of Domain Therapeutics. He is also the former chief executive at Goldfinch Bio, the kidney disease biotech that closed its doors last year.

Habib Dable

Habib Dable→ Former Acceleron chief Habib Dable has replaced Kala Bio CEO Mark Iwicki as chairman of the board at Aerovate Therapeutics, which is signing up patients for Phase IIb and Phase III studies of its lead drug AV-101 for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Dable joined Aerovate’s board in July and works part-time as a venture partner for RA Capital Management.

Julie Cherrington

Julie Cherrington→ In the burgeoning world of ADCs, Elevation Oncology is developing one of its own that targets Claudin 18.2. Its board is now up to eight members with the additions of Julie Cherrington and Mirati CMO Alan Sandler. Cherrington, a venture partner at Brandon Capital Partners, also chairs the boards at Actym Therapeutics and Tolremo Therapeutics. Sandler took the CMO job at Mirati in November 2022 and will stay in that position after Bristol Myers acquired the Krazati maker.

Patty Allen

Patty Allen→ Lonnie Moulder’s Zenas BioPharma has welcomed Patty Allen to the board of directors. Allen was a key figure in Vividion’s $2 billion sale to Bayer as the San Diego biotech’s CFO, and she’s a board member at Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, SwanBio Therapeutics and Anokion.

→ In January 2023, Y-mAbs Therapeutics cut 35% of its staff to focus on commercialization of Danyelza. This week, the company has reserved a seat on its board of directors for Nektar Therapeutics CMO Mary Tagliaferri. Tagliaferri also sits on the boards of Enzo Biochem and is a former board member of RayzeBio.

→ The ex-Biogen neurodegeneration leader at the center of Aduhelm’s controversial approval is now on the scientific advisory board at Asceneuron, a Swiss-based company focused on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Samantha Budd-Haeberlein tops the list of new SAB members, which also includes Henrik Zetterberg, Rik Ossenkoppele and Christopher van Dyck.

nasdaq covid-19 vaccine treatment fda therapy rna brazil europeInternational

Deflationary pressures in China – be careful what you wish for

Until recently, China’s decelerating inflation was welcomed by the West, as it led to lower imported prices and helped reduce inflationary pressures….

Until recently, China’s decelerating inflation was welcomed by the West, as it led to lower imported prices and helped reduce inflationary pressures. However, China’s consumer prices fell for the third consecutive month in December 2023, delaying the expected rebound in economic activity following the lifting of COVID-19 controls. For calendar year 2023, CPI growth was negligible, whilst the producer price index declined by 3.0 per cent.

China’s inflation dynamics

Chinese consumers are hindered by the weaker residential property market and high youth unemployment. Several property developers have defaulted, collectively wiping out nearly all the U.S.$155 billion worth of U.S. dollar denominated-bonds.

Meanwhile, the Shanghai Composite Index is at half of its record high, recorded in late 2007. The share prices of major developers, including Evergrande Group, Country Garden Holdings, Sunac China and Shimao Group, have declined by an average of 98 per cent over recent years. Some economists are pointing to the Japanese experience of a debt-deflation cycle in the 1990s, with economic stagnation and elevated debt levels.

Australia has certainly enjoyed the “pull-up effect” from China, particularly with the iron-ore price jumping from around U.S.$20/tonne in 2000 to an average closer to U.S.$120/tonne over the 17 years from 2007. With strong volume increases, the value of Australia’s iron ore exports has jumped 20-fold to around A$12 billion per month, accounting for approximately 35 per cent of Australia’s exports.

For context, China takes 85 per cent of Australia’s iron ore exports, whilst Australia accounts for 65 per cent of China’s iron ore imports. China’s steel industry depends on its own domestic iron ore mines for 20 per cent of its requirement, however, these are high-cost operations and need high iron ore prices to keep them in business. To reduce its dependence on Australia’s iron ore, China has increased its use of scrap metal and invested large sums of money in Africa, including the Simandou mine in Guinea, which is forecast to export 60 million tonnes of iron ore from 2028.

The Chinese housing market has historically been the source of 40 per cent of China’s steel usage. However, the recent high iron ore prices are attributable to the growth in China’s industrial and infrastructure activity, which has offset the weakness in residential construction.

Whilst this has continued to deliver supernormal profits for Australia’s major iron ore producers (and has greatly assisted the federal budget), watch out for any sustainable downturn in the iron ore price, particularly if the deflationary pressures in China continue into the medium term.

unemployment covid-19 bonds shanghai composite housing market africa chinaGovernment

Biden to call for first-time homebuyer tax credit, construction of 2 million homes

The president will announce a series of housing proposals in his 2024 State of the Union address tonight.

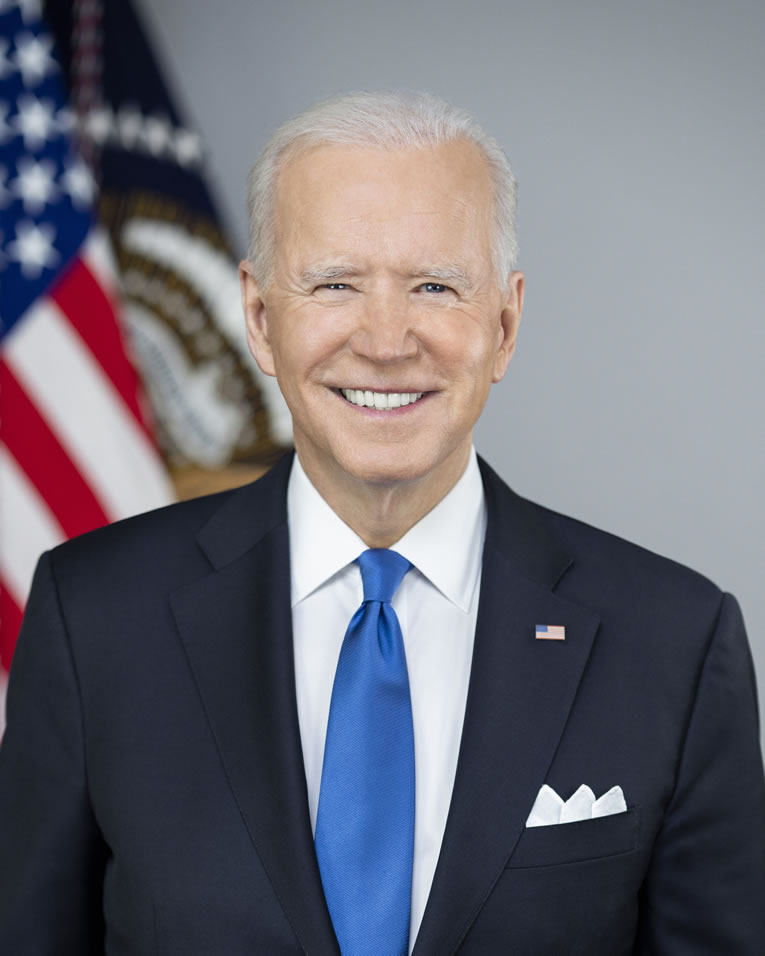

The White House announced that President Joe Biden will call on lawmakers in the House of Representatives and the Senate to address a series of housing issues in his State of the Union address, which will be delivered to a joint session of Congress and televised nationally on Thursday night.

In the address, the president will call for a $10,000 tax credit for both first-time homebuyers and people who sell their starter homes; the construction and renovation of more than 2 million additional homes; and cost reductions for renters.

Biden will also call for “lower homebuying and refinancing closing costs and crack down on corporate actions that rip off renters,” according to the White House announcement.

The mortgage relief credit would provide “middle-class first-time homebuyers with an annual tax credit of $5,000 a year for two years,” according to the announcement. This would act as an equivalent to reducing the mortgage rate by more than 1.5% on a median-priced home for two years, and it is estimated to “help more than 3.5 million middle-class families purchase their first home over the next two years,” the White House said.

The president will also call for a new credit to “unlock inventory of affordable starter homes, while helping middle-class families move up the housing ladder and empty nesters right size,” the White House said.

Addressing rate lock-ins

Homeowners who benefited from the post-pandemic, low-rate environment are typically more reluctant to sell and give up their rate, even if their circumstances may not fit their needs. The White House is looking to incentivize those who would benefit from a new home to sell.

“The president is calling on Congress to provide a one-year tax credit of up to $10,000 to middle-class families who sell their starter home, defined as homes below the area median home price in the county, to another owner-occupant,” the announcement explained. “This proposal is estimated to help nearly 3 million families.”

The president will also reiterate a call to provide $25,000 in down payment assistance for first-generation homebuyers “whose families haven’t benefited from the generational wealth building associated with homeownership,” which is estimated to assist 400,000 families, according to the White House.

The White House also pointed out last year’s reduction to the mortgage insurance premium (MIP) for Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgages, which save “an estimated 850,000 homebuyers and homeowners an estimated $800 per year.”

In Thursday’s State of the Union address, the president is expected to announce “new actions to lower the closing costs associated with buying a home or refinancing a mortgage,” including a Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) pilot program that would “waive the requirement for lender’s title insurance on certain refinances.”

The White House says that, if enacted, this would save thousands of homeowners up to $1,500 — or an average of $750.

Supply and rental challenges

Housing supply continues to be an issue for the broader housing market, and the president will call on Congress to pass legislation “to build and renovate more than 2 million homes, which would close the housing supply gap and lower housing costs for renters and homeowners,” the White House said.

This would be accomplished by an expansion of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) to build or preserve 1.2 million affordable rental units, as well as a new Neighborhood Homes Tax Credit that would “build or renovate affordable homes for homeownership, which would lead to the construction or preservation of over 400,000 starter homes.”

A new $20 billion, competitive grant program the president is expected to unveil during the speech would also “support the construction of affordable multifamily rental units; incentivize local actions to remove unnecessary barriers to housing development; pilot innovative models to increase the production of affordable and workforce rental housing; and spur the construction of new starter homes for middle-class families,” the White House said.

Biden will also propose that each Federal Home Loan Bank double its annual contribution to the Affordable Housing Program, raising it from 10% of prior year net income to 20%. The White House estimates that this “will raise an additional $3.79 billion for affordable housing over the next decade and assist nearly 380,0000 households.”

Biden will propose several new provisions designed to control costs for renters, including the targeting of corporate landlords and private equity firms, which have been “accused of illegal information sharing, price fixing, and inflating rents,” the White House said.

The president will also reference the administration’s “war on junk fees,” targeting those that withstand added costs in the rental application process and throughout the duration of a lease under the guise of “convenience fees,” the White House said.

And Biden is expected to call on Congress to further expand rental assistance to more than 500,000 households, “including by providing a voucher guarantee for low-income veterans and youth aging out of foster care.”

Housing association responses

Housing associations such as the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) and the National Housing Conference (NHC) quickly responded to the news. The NHC lauded the development.

“This is the most consequential State of the Union address on housing in more than 50 years,” NHC President and CEO David Dworkin said. “President Biden’s call for Congress to tackle the urgent matter of housing affordability through tax credits, down payment assistance initiatives, and other measures is warranted and represents a crucial step in easing the burden of high rents and home prices.”

MBA President and CEO Bob Broeksmit explained that while the association will review all of the proposals in-depth, it welcomes the Biden administration’s focus on reforms that can expand single-family and multifamily housing supply. It is also wary of some of the proposals.

“MBA has significant concerns that some of the proposals on closing costs and title insurance could undermine consumer protections, increase risk, and reduce competition,” Broeksmit said. “Suggestions that another revamp of these rules is needed depart from the legal regime created by Congress in the Dodd-Frank Act and will only increase regulatory costs and make it untenable for smaller lenders to compete.”

housing market pandemic white house congress senate house of representatives-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges