Spread & Containment

Lockdown’s Fourth Birthday

Lockdown’s Fourth Birthday

Authored by Kit Knightly via Off-Guardian.org,

Last weekend marked four years to the day since the UK went into…

Authored by Kit Knightly via Off-Guardian.org,

Last weekend marked four years to the day since the UK went into “lockdown” for the first time.

What an exciting time that was, right? With the pan-banging and the curve-flattening and the Spirit of the Blitz living on. Good times.

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s team decided to honour the occasion by slapping themselves on the back:

4 years ago today, @RishiSunak saved our economy. pic.twitter.com/mzmLTmD8ca

— Conservatives (@Conservatives) March 20, 2024

Needless to say, this is revisionism of the highest order. To quote my favourite reply, it’s the “gaslightiest gaslight I’ve ever been gaslit by”.

The furlough system did not “save the economy”. The economy was not saved. Rather, it was laid out on a stone table and slowly flayed with a sharpened flint.

We are all still living with the consequences of lockdown, not just in the UK but globally. The world over, hundreds of millions of people have been plunged into extreme poverty by so-called “anti-Covid measures”.

Billions more are worse off, paying more for almost every product and service, and struggling in general.

It’s important to remember this was the point.

As we wrote in our piece addressing Covid revisionism last year:

The poverty, the depression, despair. The shuttered stores and closed hospitals and bankrupt businesses. They were all predictable, and all deliberate. They knew that’s what would happen…that’s what it was for. That’s why “Covid” was invented. Lockdown was not a policy mistake, it was a policy success.

Lockdowns killed more people than they saved. Lockdowns doubled global child poverty.

Lockdown doesn’t work, it never worked and it wasn’t supposed to work.

And the only thing more nauseating than the anti-human trolls pushing it at the time, are the same anti-human trolls re-writing history since, claiming lockdowns were a mistake or a panic reaction, or that no one could have known how much damage they would do.

As we wrote in our piece marking Lockdown’s first birthday:

Too often soft language in the media talks about “misjudgments” or “mistakes” or “incompetence”. Supposed critics claim the government “panicked” or “over-reacted”. That is nonsense. The easiest, cheesiest excuse that has ever existed.

“Whoops”, they say, with an emphatic shrug and shit-eating grin “I guess we done messed up!”. Unflattering, but better than the truth.

Because the truth is that the government isn’t mistaken or scared or stupid…they are malign. And dishonest. And cruel.

All the suffering of lockdown was entirely predictable and deliberately imposed. For reasons that have nothing to do with helping people and everything to do with controlling them.

It’s been more than apparent for most of the last fifty-two weeks that the agenda of lockdown was not public health, but laying the groundwork for the “new normal” and “the great reset”.

A series of programmes designed to completely undercut civil liberties all across the world, reversing decades (if not centuries) of social progress. A re-feudalisation of society, with the 99% cheerfully taking up their peasant smocks “to protect the vulnerable”, whilst the elite proselytise about the worth of rules they happily admit do not apply to them.

Lockdown was not a policy mistake it was murder.

This revisionism isn’t just about protecting reputations or saving face, of course, but about establishing a couple of important new “truths”:

-

Lockdowns are responsible for post-Covid excess deaths, NOT the experimental “vaccines”.

-

Lockdowns were so bad that we need to do anything we can to avoid using them for the next pandemic, including vaccine mandates and quarantine camps.

In the future we may see another lockdown – for terrorism or climate or “disease X” – but we might not. It might be we never see another lockdown again.

Either way, it’s a policy which realised its goal.

Massive unemployment. Massive misery. Massive state-overreach. Normalizing Orwellian police raids for private actions on private property, increasing snitch culture, and promoting fear and resentment of your neighbours.

Drugs, depression, suicide up. Prosperity happiness and freedom down.

And most importantly, they now know they can get away with it. They wanted to see what we would do, and for the most part the answer was “nothing”.

It was a test, and most people failed.

As I wrote two days before lockdown was announced in 2020:

“Special powers” don’t go away. They are not temporary, they won’t be surrendered. Everything we give the government our permission to do, they will do. For the foreseeable.

And now CBDCs and edible insects and 15 minute cities are on the way. They will continue to do what they want, because they think we’ll continue to let them.

Hopefully, next time, we’ll prove them wrong.

Government

Capital Confusion at the New York Times

In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution claims that the merger between Capital One and Discover would…

In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution claims that the merger between Capital One and Discover would “keep intact the broken and predatory system in which credit card companies profit handsomely by rewarding our richest Americans and advantaging the biggest corporations.”

That’s quite an indictment! Fortunately, Klein also offers solutions. Phew!

But really, it’s difficult to understand how someone could describe the highly innovative, dynamic, and efficient U.S. credit-card system as “broken.” If it were, why would U.S. credit-card networks like Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover be the world leaders, accounting for more than 60% of global market share?

And far from being “predatory,” credit cards have been hugely valuable to American families at all income levels. During the pandemic, they literally saved lives by enabling people in lockdown to buy food online and have it delivered to their homes. As Klein himself notes:

The pandemic changed how we buy things, significantly increasing the share of transactions put on credit cards rather than conducted in cash.

Klein tries to turn this positive into a negative, noting that the increase in card use added “to the swipe fees merchants pay.” What he fails to mention is that the switch from cash to credit has, in general, reduced merchants total costs because the costs of handling cash are so much higher. When a customer pays in cash, checkout takes longer than paying with a card (especially where the transaction is contactless). For larger stores, that means more cash-register operators must be hired. For smaller stores, it means there are less resources available to perform other tasks, such as taking inventory or restocking shelves.

Cash also presents a greater risk of theft, which means merchants must invest in security systems both in-store and for moving cash to the bank. And cash must be counted and deposited, both of which take time.

Study after study has shown that, when all relevant costs are taken into account, cash costs merchants more than payment cards. A 2018 study by the IHL Group, for example, found that the cost of accepting cash averaged about 9% and ranged from 4.7% for larger grocery stores to 15.5% for bars and restaurants. By contrast, the all-in cost of processing credit-card payments is typically less than 3%.

Klein’s sources don’t inspire much confidence. The link in his opening paragraph is not to an academic study, but to a video on the Times’ own website that spins an elaborate tale of how a frying pan bought using credit-card rewards was actually paid for by MJ, the owner of a local convenience store. In essence, the video asserts that, by using a rewards credit card to buy $100 of goods every week for a year at MJ’s store, enough rewards were accrued to pay for the frying pan.

Let’s suppose that the bank that issued the rewards card charged the maximum interchange fee on the transactions at MJ’s store, which in 2023 was 3.15%. Further assume that MJ’s merchant-account provider charges her on an “interchange-plus” basis. If MJ used Helcim, she would pay the interchange fee plus 0.4%, plus $0.08 per transaction.

So, of the $5,200 spent over the course of the year by the customer using a rewards card, $163.80 would go to the issuing bank and $28.80 to Helcim, leaving MJ with a net of $5,007.40. By contrast, if MJ had been paid in cash, she would have a net of $4,768.4 (based on the average costs identified by IHL for convenience stores of 8.3%).

While the Times video wants our hearts to bleed for MJ having to pay for a customer’s All-Clad D5 12” frying pan, had the customer paid her in cash instead, she would have made $239 less. And the customer would have been less happy, because he would have effectively paid about $250 more (the cost of the pan). In other words, paying with cash would make the merchant and the consumer worse off to the tune of nearly $500.

Credit cards also have other benefits that Klein ignores in his simplistic story. By providing credit—including up to 45 days interest free for cardholders who pay off their balance each month—credit cards enable people to smooth their spending so that they can buy items even when they don’t have money in the bank. They also provide fraud and theft protection for the cardholder, making it far less risky to carry a card than a bundle of cash. Many cards also include payment-protection insurance, rental-car insurance, and travel insurance.

Finally, credit cards make it far easier to trace payments, because the card issuer knows the identity and address of the legitimate user. This makes it more difficult to make illegal purchases using credit cards (compared to relatively untraceable cash) and easier to enforce sales taxes.

This highlights a fundamental problem with Klein’s analysis: he counts the costs of paying with credit cards but fails to explain for what would happen in the alternative. He wants us to believe that:

the rest of us, whether we pay with cash, a debit-card or a middle-of-the-road credit card, wind up paying more—because we are subsidizing these rewards cards for whom only the wealthiest qualify.

Except that’s just not true.

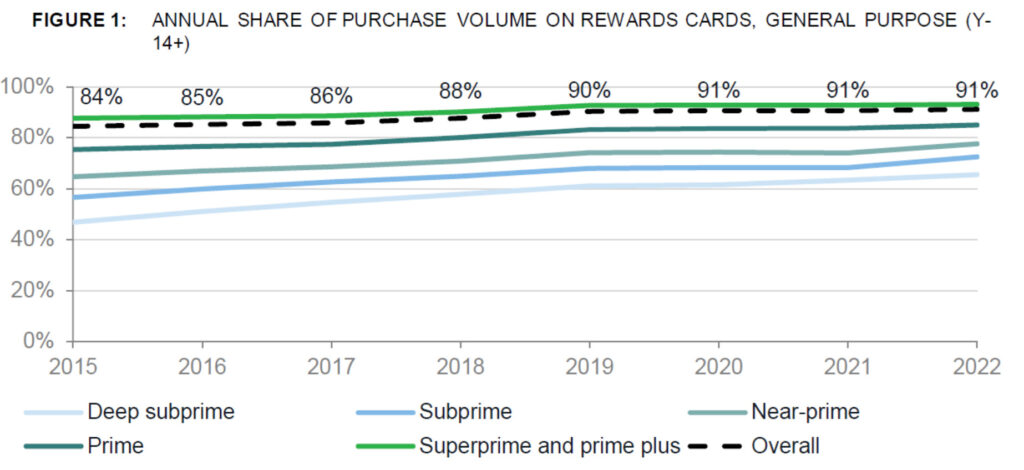

First, as noted, in most cases, cash purchases are more costly for store owners, so credit-card users are subsidizing cash users. Second, as Todd Zywicki, Ben Sperry, and I have noted, and as can be seen in the figure below from the most recent Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) report on the consumer credit-card market, access to rewards credit cards is less a function of income and more a function of the cardholder’s credit score. Third, as the figure also shows, more than 90% of all credit-card transactions are made using rewards cards.

Fourth, as can be seen in the chart below, and as the CFPB noted in the accompanying text: “Earning rates are about the same across credit score tiers for those with rewards cards, except for consumers with scores above 800.” Perhaps Mr. Klein does not have access to those higher-value rewards cards, but if so, he is the exception, not the rule.

These data suggest that, for all the critics’ bluster, the value of rewards per dollar spent varies relatively little from card to card; what differs is the types of rewards and other associated benefits. Innovations along these lines have been important drivers in the shift from cash and checks to credit cards, with attendant benefits for consumers, merchants, and society as a whole.

Nonetheless, Klein is correct that the fees charged for different cards can vary significantly. In fact, importantly, the story is rather more complicated than Klein makes out. Interchange fees typically vary not only by card, but also by type of merchant. This is, at least in part, because different merchants pose different risks of fraud and chargeback.

Moreover, in contrast to Klein’s assertion that low-dollar sales typically have high fees, networks often discount the fees on small-ticket items in order to encourage adoption. For transactions of $15 or less, Visa’s small-ticket interchange fee for credit cards carries no fixed-fee component. For transactions of $5 or less, Mastercard’s fixed fee is only $0.04. And in some cases, such as for gasoline purchases, they cap the total amount (for example, Mastercard charges a maximum of $0.95 and Visa a maximum of $1.10 for gas).

Nonetheless, Klein offers the anecdote that, one year, his “oldest friend’s small coffee shop paid more in card processing costs than for coffee beans.” In fairness, the coffee shop in question, Bump n Grind in Maryland, roasts its own beans, and therefore buys green beans that are considerably less expensive than pre-roasted beans. It also sells much more than just coffee, including vinyl records. So it probably has many costs that are higher than the amount it pays for beans, including: rent, equipment, utilities, and staff.

It may also use a merchant acquirer or a payment gateway (such as Square or Stripe) that offers blended rates (that is, a single rate for all transactions regardless of the type of card or size of transaction), which would mean that it is unable to take advantage of the small-ticket discount available on “interchange-plus” plans.

‘Solutions’ Far Worse Than the ‘Problem’

Klein lays much of the blame on the U.S. Supreme Court for the alleged problem of consumers being charged different swipe fees for different cards issued on the same payment network. He claims that “a 2018 Supreme Court ruling effectively forces merchants to accept either every type of card – from, say, a basic Green Card to the Platinum Card – from an issuer like Amex or none of them.” And he goes on to assert that “the ruling also barred merchants from incentivizing consumers to use cheaper ones.”

There’s just one problem with these claims: they’re not true.

What the Supreme Court did in Ohio v. Amex was to prevent the state from overriding the contractual “anti-steering” provisions that had long been established by credit-card networks in their agreements with merchants (either directly, in the case of three-party cards such as Amex and Discover, or via agreements with issuers, in the case of four-party cards like Visa and Mastercard). The Court explained its rationale clearly:

Respondent… Amex… operate[s] what economists call a “two-sided platform,” providing services to two different groups (cardholders and merchants) who depend on the platform to intermediate between them. Because the interaction between the two groups is a transaction, credit-card networks are a special type of two-sided platform known as a “transaction” platform. The key feature of transaction platforms is that they cannot make a sale to one side of the platform without simultaneously making a sale to the other. Unlike traditional markets, two-sided platforms exhibit “indirect network effects,” which exist where the value of the platform to one group depends on how many members of another group participate. Two-sided platforms must take these effects into account before making a change in price on either side, or they risk creating a feedback loop of declining demand. Thus, striking the optimal balance of the prices charged on each side of the platform is essential for two-sided platforms to maximize the value of their services and to compete with their rivals.

Visa and MasterCard—two of the major players in the credit-card market—have significant structural advantages over Amex. Amex competes with them by using a different business model, which focuses on cardholder spending rather than cardholder lending. To encourage cardholder spending, Amex provides better rewards than the other credit-card companies. Amex must continually invest in its cardholder rewards program to maintain its cardholders’ loyalty. But to fund those investments, it must charge merchants higher fees than its rivals. Although this business model has stimulated competitive innovations in the credit-card market, it sometimes causes friction with merchants. To avoid higher fees, merchants sometimes attempt to dissuade cardholders from using Amex cards at the point of sale—a practice known as “steering.” Amex places antisteering provisions in its contracts with merchants to combat this.

While these anti-steering provisions are important, they are not the provisions to which Klein refers, which are known as “honor-all-cards” provisions and which prevent merchants from discriminating against cards bearing the network’s brand. Nonetheless, honor-all-cards provisions are likewise important to the functioning of two-sided payment networks (as Nobel laurate economist Jean Tirole has noted) because they enable card networks to create a range of offerings, thereby facilitating innovation by and competition among issuers.

Without the honor-all-cards provisions, merchants might refuse to accept cards with higher interchange fees. Klein seems to think this is a good idea. He proposes that:

Congress should legislatively correct the Supreme Court’s mistake. For starters, give merchants the power to reject the priciest credit cards, and let’s see if their users are willing to pay the true cost of their rewards.

But this would result in a race to the bottom in which card issuers were unable to offer rewards or otherwise differentiate their products, leading to a decline in the use of cards. This, in turn, would reduce spending, harming both consumers and merchants.

Klein supports his argument that Congress could override the honor-all-cards provision by citing the Durbin amendment, which imposed price controls on debit-interchange fees. A recent study by Vladimir Mukharlyamov of Georgetown University and Natasha Sarin of the University of Pennsylvania found that this had the effect of reducing covered banks’ annual revenues by about $5.5 billion. Seeking to recoup some of the lost revenue, banks on average doubled their monthly fees on checking accounts; increased the minimum deposit required for “free” checking by 21%; and reduced the availability of accounts with no-minimum free checking by about half.

Likely as a direct consequence, hundreds of thousands of the poorest Americans left the banking system altogether. Meanwhile, merchants passed through little, if any, of the savings resulting from the reduced debit-interchange fees, so those on low incomes who kept their accounts but paid monthly fees were measurably worse off.

To make matters worse, Klein wants “brave policymakers” to “start taxing reward points.” At least he is clear that this is really just about taxing the rich:

The richer you are, the more likely you qualify for bigger rewards. Progressive taxation rates mean that exempting rewards from taxation makes them nearly four times as valuable to those in the top tax bracket as the bottom.

As it happens, some credit-card rewards probably are taxable; it depends on their function. But if policymakers were to make all rewards taxable, it would harm those that function primarily as rebates and loyalty incentives—such as airline miles received on co-branded cards. And that, in turn, would harm the co-brand partners, such as airlines and hotels.

Klein’s final proposal is more troubling. He suggests that “we could require all merchants have access to the same swipe-fee pricing, regardless of size.” His concern here is that some larger merchants leverage their bargaining power to obtain lower interchange fees. In part, larger merchants benefit from economies of scale and can implement transaction monitoring and security systems that smaller merchants simply can’t afford.

Meanwhile, a few large merchants (such as Costco) operate membership-based systems that enable them to forego customer convenience and strike exclusive deals with specific card issuers and networks, thereby obtaining lower swipe fees. Neither of these apply to individual smaller merchants, so the suggestion that swipe fees could be reduced by mandate to the levels negotiated by larger merchants is totally unrealistic.

In his last few paragraphs, Klein returns to the merger between Capital One and Discover, the hook around which he has hung a series of shibboleths about credit cards that he uses as the premise for his terrible policy proposals. And here again, he repeats those shibboleths, moaning that:

Capital One already seems to be competing with American Express for wealthy customers who like elite airport lounges and bit travel perks …

And in the next paragraph:

As the economy continues to digitize with more micropayments, the credit card burden will keep growing, particularly on smaller businesses.

And in the final paragraph:

Until legislators are willing to change the system that showers tax-free rewards on the upper middle class, the cash register will continue to exacerbate the wealth gap.

What utter tosh.

The post Capital Confusion at the New York Times appeared first on Truth on the Market.

link pandemic congress lockdownSpread & Containment

The Norwegian Illusion: EVs Are Not More Energy Efficient

The Norwegian Illusion: EVs Are Not More Energy Efficient

Via Goehring & Rozencwajg,

“Electric vehicles (EVs) are pilling up on lots…

“Electric vehicles (EVs) are pilling up on lots across the country as the green revolution hits a speed bump, data show.”

~ USA Today, November 14, 2023“Hertz Global Holdings announced Thursday it planned to cut one-third of its global EV fleet over the year. Following the announcement, Hertz CEO Stephen Scherr suggested the road to electrification could be bumpier than anticipated.”

~ Bloomberg, January 11, 2024

Starting mid-point last decade, the investment community became convinced EV adoption would quickly surge. EV penetrations would become so great that global oil consumption would imminently peak, or so consensus opinion widely believed. 2019 was repeatedly referenced as the year that oil demand would peak and then decline. In retrospect, these concerns were misplaced. Despite the massive COVID-19 disruption, oil demand in 2024 should reach 103 m b/d – 2.3 m b/d greater than 2019. Undeterred by the surprising surge in demand, many analysts remain convinced that “peak oil demand” is still imminent.

The investment community’s belief that EVs will displace the internal combustion engine remains as strong as ever.

We vigorously disagree.

In our last letter, we predicted that global energy demand would consistently exceed expectations for the next twenty years. Never before have so many people been simultaneously in their period of energy-intensive economic development. Our essay focused broadly on total energy demand and specifically avoided oil consumption. Our choice was deliberate: we wanted to highlight the critical drivers of total energy demand and avoid getting distracted by the debate on EV penetration. Today’s essay focuses on oil and explains why we believe demand will surprise the upside for years to come.

Our research shows that EVs will struggle to achieve widespread adoption despite massive subsidies and the growing threat of outright internal combustion engine (ICE) bans. After carefully studying the history of energy, we have yet to find an example where a new technology with inferior energy efficiency has replaced an existing, more efficient one. Despite claims to the contrary, our research suggests EVs are less energy efficient than internal combustion engine automobiles. As a result, they will fail to gain widespread adoption.

Our claim is controversial; most pundits insist EVs are far more efficient. We believe the ICE is clearly the winner once the energetic costs of both the battery and the renewable power required to make “carbon-free” EVs are considered.

Although governments can encourage EVs through either subsidies or ICE bans, these measures will likely fail, as consumers will ultimately refuse to embrace a new technology that sports inferior energy efficiency. Better examples couldn’t exist than Ford and Hertz dramatically scaling back their EV initiatives due to lower-than-expected consumer interest.

Mitigating carbon emissions is central to the case for electric vehicles. Advocates argue that displacing fossil fuels is essential to curbing global warming. We disagree. Replacing ICEs with EVs will materially increase carbon emissions and may worsen the problem. Manufacturing an electric vehicle consumes far more energy than an ICE. Most of this additional energy is spent mining the materials for and manufacturing an EV’s giant lithium-ion battery. Mining companies use energy-intensive trucks, crushers, and mills to extract each battery’s nickel, cobalt, lithium, and copper. The manufacturing process consumes vast amounts of energy as well. Many analysts eagerly tout the carbon savings from displaced fossil fuels without adequately accounting for the battery’s increased energy consumption. Once these adjustments are made, most, if not all, of the EV’s carbon advantage disappears.

If our models are correct, EVs will fail on two fronts: they are less energy efficient than the ICEs they are trying to replace and their adoption will do little to mitigate carbon emissions.

Policymakers often tout Norway as the ultimate EV success story. Thanks to massive subsidies, EVs made up 80% of all Norwegian new car sales in 2022 and currently account for 20% of the total car fleet. Policymakers hope all developed countries will ultimately adopt Norway’s model. However, upon closer inspection, Norway's experience does more to warn of EVs’ shortcomings than advocate for their adoption.

The first problem is financial.

The Norwegian government offers consumers massive subsidies to purchase an EV. New vehicles are exempt from several onerous taxes and the 25% VAT. On average, a large new ICE would be subject to $27,000 in various taxes; an equivalent EV would pay none. Next, Norway exempts EVs from any road or ferry tolls and allows them to use bus lanes, offers free parking and charging in municipal areas, and ensures “charging rights” in apartment buildings. Although Norway rolled back some of these operating subsidies starting in 2017, an Oslo resident can still expect these benefits to total $8,000 annually.

Norway is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, with a per capita GDP of $106,000 in 2022. Despite its impressive wealth, the government must still financially incentivize its citizens to purchase EVs.

The benefits are starting to take their toll on Norway’s finances. At nearly $4 billion annually, Norway spends as much on EV subsidies as on total highway and public infrastructure maintenance. The program has also raised significant issues around equality in Norway. EV subsidies favor high-income urban citizens, who take advantage of free tolls, parking, and charging and avoid the onerous tax on larger luxury vehicles. Several populist-leaning political groups in Norway have made so-called “elitist” EV subsidies a focal point of their platform.

Amid growing scrutiny, the government has actively sought to reduce several subsidies. Municipal parking is no longer free, and passengers (although not the vehicles themselves) are subject to certain tolls. The government also introduced a partial purchase tax on new EVs. Proponents have warned that any rollback of subsidies will surely harm EV penetration and offer Sweden as a case study, where, in 2022, the elimination of several subsidies precipitated a 20% drop in EV sales.

More important, EVs in Norway have not affected fossil fuel demand or carbon emissions as expected. Although oil demand and carbon emissions have fallen by 15% since 2010, most of this is unrelated to EV sales. Over the period, total oil demand fell by only 34,000 b/d, with gasoline and diesel making up a mere 10% of the decline. Most of the decline came from heating, lighting, and petrochemical demand, which we estimate collapsed by more than a third. Despite 20% of all vehicles on the road now being electric, Norway’s gasoline and diesel demand fell by a mere 4%.

Our data suggests that Norwegians are reluctant to give up their ICE vehicles, even after purchasing an EV. We calculate that two-thirds of Norway’s EV households own at least one ICE vehicle. From 2010 to 2022, Norway added 550,000 EVs, but the number of ICE vehicles on the road, rather than falling, increased by 32,630. While the population grew by 11%, the total number of passenger cars grew by 25%. When an EV household prefers to avoid a road or ferry toll, have access to free parking or charging, or avoid congestion by using bus lanes, they use their EV. When they visit their hytte in the mountains, they use their ICE. The impact has been so material that advocates have lobbied for a government-funded ICE scrappage program,- another veiled EV subsidy.

Unsurprisingly, electricity demand has surged as Norway shifted from fossil fuels to electricity for transportation, heating, and lighting. Since 2010, Norwegian electricity demand rose an impressive 20%. Total primary demand for all forms of energy increased by 5%. The data suggests that a widespread shift to EVs did little to reduce overall energy consumption despite claims they are far more efficient.

The shift from fossil fuels to electricity has reduced Norway’s CO2 by an impressive 16%, an achievement lauded in the press. Far less discussed, however, is how the US lowered its emissions by 16% over the same period, by switching from coal to natural gas in its power generation.

Using Norway as a model for CO2 reduction would be a mistake. Far more than any other country in the world, Norway benefits from its vast hydrological potential which generates nearly 92% of all electricity carbon-free. Therefore, a move from fossil fuels towards electricity will significantly impact Norway’s carbon emissions more than anywhere else on Earth.

Furthermore, Norway imports all domestic EVs. As we discussed, EV manufacturing is incredibly energy-intensive, mainly to build the battery. In Norway’s case, none of this additional energy is reflected in their domestic demand figures. China manufactures most lithium-ion batteries and 80% of all EVs. Coal accounts for 60% of their total energy supply.

We estimate an average EV consumes 60 MWh to manufacture, of which the battery represents half. Therefore, manufacturing Norway’s 579,000 EVs (all the EVs on the road today in Norway) requires 35 twh, equivalent to 25% of the total annual Norwegian electricity demand. Given that China emits 600 grams of CO2 per kwh (China is where almost all of Noway’s EV batteries are manufactured), we calculate Norway’s EV fleet would emit 21 mm tonnes of CO2. Norway’s gasoline and diesel consumption fell by a meager 3,200 barrels per day or 50 mm gallons per year. Assuming 9 kg of CO2 per gallon of gasoline or diesel, Norway’s entire EV fleet mitigates a mere 450,000 tonnes of CO2 per year, compared with an upfront emission of 21 mm tonnes. In other words, it would take forty-five years of CO2 savings from reduced gasoline and diesel consumption to offset the initial emissions from the manufacturing of the vehicles. Since an EV battery has a useful life of only ten to fifteen years, it is clear that Norway’s EV rollout has increased total lifecycle CO2 emissions dramatically. Incredibly, this is true despite Norway having the lowest carbon hydroelectricity in the world. Even if China were to reach its overly ambitious targets for wind, solar, and nuclear power by 2035, we calculate that the carbon “payback” would still exceed twenty years. Realistically, the only way for EVs to reduce lifecycle carbon emissions would be with a widespread move to carbon-free energy in EV manufacturing. Most EV advocates hope renewable energy will be the solution. Unfortunately, we do not believe this will prove feasible due to their inferior energy efficiency.

Instead of serving as a model, Norway’s program should warn of the unintended consequences of large-scale EV penetration, particularly when consumers purchase an EV in addition to an ICE. Countless articles claim EVs are far more energy efficient than ICE vehicles. Moreover, these authors argue EVs will be more efficient and more carbon-free once renewables replace coal and natural gas. Our analysis, unpopular and controversial, suggests the opposite.

Most articles list EVs as anywhere between two and three times more energy efficient than the ICEs they replace.

The basis for this claim is that internal combustion engines are only 40% efficient and that nearly 60% of the energy contained in gasoline or diesel fuel is “wasted,” –mainly in the form of heat and friction. On the other hand, an electric motor transfers nearly 90% of its electrical energy directly to the wheels. The difference leads many to erroneously conclude that an EV is almost three times as “efficient” as an ICE.

This common argument is fundamentally flawed for three reasons.

First, it fails to capture the energy needed to make the battery;

second, it fails to distinguish between thermal and electric energy;

and third, it fails to account for the poor energy efficiency of renewable energy.

An EV uses 32 kWh of electricity per 100 miles traveled. The vehicle’s battery, meanwhile, consumes an incredible 24 MWh in its manufacturing. Assuming a useful life of 120,000 miles, the battery pack consumes 20 kWh per 100 miles traveled, two-thirds as much as the direct electricity itself. Most analysts we have read fail to include this onerous energy burden when touting the EV’s superior efficiency.

Next, most efficiency arguments fail to distinguish between thermal and electrical energy.

While most of us have been taught that energy is fungible, several distinct forms of energy have differing degrees of usefulness. Although it is beyond the scope of this essay, the distinction surrounds the randomness, or entropy, of the energy carrier. The more entropic an energy source, the less useful work it can perform. Burning fuels of any kind always has high entropy. Electricity, on the other hand, with its orderly string of moving electrons, has extremely low entropy. Upgrading from thermal to electric energy always introduces predictable inefficiencies based on the fundamental laws of thermodynamics.

When pundits claim an EV is three times more efficient than an ICE, they fail to make this distinction. In a combustion engine, the driver converts gasoline (high entropy) into forward motion with approximately 40% efficiency. Electricity (low entropy) drives a motor with approximately 90% efficiency in an electric vehicle. However, electricity does not exist in nature but instead must be generated. Burning natural gas (high entropy) to generate electricity (low entropy) is only 40-50% efficient. The EV is not inherently more efficient; instead, the inefficient “upgrade” from thermal to electric energy occurs off-stage and is conveniently omitted by most analysts.

Last, most efficiency arguments fail to account for energy generation in the first place.

For example, as we saw with Norway, the only way to lower automotive carbon emissions is by converting to renewable energy for both the manufacturing and powering of the vehicle. Unfortunately, renewable power is prohibitively inefficient. This may be surprising. After all, neither wind nor solar “burn” fuel, and so are not subjected to the inefficiency of moving from thermal to electric energy discussed earlier. However, wind and solar suffer from incredibly low energy density (consider the heat from a gas stove compared to a stiff breeze). To capture useful quantities of power, windmills must stand 300 m tall, and solar farms must spread out over thousands of acres. These large installations require raw materials like steel, cement, copper, silver, and polysilicon. These materials, in turn, consume vast quantities of energy to both mine and process. By comparison, oil and gas extraction is highly efficient.

We study the total energy required to produce various forms of energy, a metric known as energy return on investment (EROI). While a single unit of invested energy might generate fifty units of (thermal) energy over the life of a productive oil well, it will only generate ten units of (electrical) energy with wind or less than six from a solar panel. Furthermore, wind and solar power must be buffered by grid-level battery storage to avoid intermittency, which requires far more energy. Fully buffered wind likely has an EROI of six to seven, while solar may be as low as three. Claiming a renewable-powered EV is efficient because its motor operates at 90% fails to account for the poor upstream efficiency.

Instead, we have taken a completely different approach when calculating automotive efficiency: assuming 100 kWh of available thermal energy, how far can a driver expect to travel in an ICE compared with an EV. We prefer this methodology, as it aligns with our intuitive understanding of “efficiency:”: how much can we get out of a single unit of energy. Using this approach, the race isn’t even close --the ICE wins “hands down.”

An efficient ICE can expect to achieve 37 miles per gallon of gasoline or 98 kWh of thermal energy per 100 miles. The vehicle components require 20 MWh, or 15 kWh per 100 miles, when amortized over a useful life of 170,000 miles—according to Argon Labs. The ICE can expect to consume 112 kWh per 100 miles, of which 90% represents thermal energy in the form of gasoline. Oil extraction benefits from a very high EROI of 60:1 at the wellhead. In other words, 60 units of thermal energy, in the form of crude, comes up the wellbore for every unit of energy invested. Transportation and refining consume approximately 15% of the energy contained in the crude, lowering the EROI to 50. To be conservative, we are assuming an ultimate EROI of 45. Therefore, investing one kWh of thermal energy will create 45 kWh of thermal energy, propelling the ICE 41 miles.

A modern EV consumes 32 kWh of direct electrical energy per 100 miles. The battery requires an additional 24 MWh, which over the vehicle’s useful life of 120,000 miles equals 20 kWh per 100 miles. The remaining vehicle components consume 27 kWh per 100 miles. The EV can expect to consume 80 kWh per 100 miles, of which 95% is electricity.

Assuming the electricity is generated in a natural gas-fired power plant, the EROI is approximately 25 once transmission line losses are considered. Starting again with one kWh of thermal energy, we would expect to generate 25 kWh of electricity. The EV would, therefore, travel 32 miles – 20% less than the ICE. If electricity is generated using a mixture of unbuffered wind and solar, the EROI could be as low as 13. Therefore, one kWh of energy would only generate 13 kWh of electricity, propelling the EV a mere 16 miles – over 60% less than the ICE.

Never in history has a less efficient “prime mover” displaced a more efficient one. We believe this time will be no different. While governments may try to coerce drivers into buying EVs or even ban ICE altogether, these policies will ultimately fail as consumers insist on keeping their more efficient vehicles. A new battery breakthrough would help make EVs more energy efficient, and we are studying the space very closely. In particular, we are impressed with the work being done by the team at PureLithium, in which we have made a small private investment. However, we cannot identify any battery technology that would materially change this analysis. Until then, we expect internal combustion engines will continue to dominate, and EV penetration will disappoint.

Intrigued? We invite you to download or revisit our entire Q4 2023 research letter, available below.

Spread & Containment

A top Disney World rival is planning to implement ‘surge pricing’

The popular theme park attraction is planning to follow in the footsteps of its competitor, and fans may not be happy about the move.

Disney World rival Legoland may be the next popular institution to implement a major change to its pricing that consumers have recently been extremely resistant to.

Scott O’Neil, the CEO of Merlin Entertainments, which owns Legoland, Madame Tussauds and Peppa Pig Theme Park, just revealed in a new interview with The Financial Times that his company is currently developing a dynamic pricing model, better known as “surge pricing,” for its attractions. Dynamic pricing is when the price of a product/service is adjusted based on the time of day and other factors such as consumer habits and demographics.

Related: Wendy’s is planning a major price change, and customers aren’t happy

O’Neil claims in the interview that the change will make customers pay more for tickets at its attractions during peak summer weekends than on rainy weekends in the off-season. The change will take place at its top 20 global attractions by the end of the year, and in major U.S. attractions next year.

“If [an attraction] is in the UK, it’s August peak holiday season, sunny and a Saturday, you would expect to pay more than if it was a rainy Tuesday in March,” said O’Neil.

O’Neil also revealed during the interview that the dynamic pricing model will help the company make up for the money it lost during the Covid pandemic as it experienced a decrease in foot traffic at its attractions.

In a recent report of the company's performance, Merlin Entertainments reveals that it's seeing a normalization of consumer demand at its theme parks.

“With no material COVID-19 related attraction closures remaining, our operational footprint has now largely returned to pre-pandemic levels,” said the company in the report.

If Legoland implements dynamic pricing, it won’t be the first major theme park to do so. Since 2018, Disney has used dynamic pricing to charge more money for tickets at its theme parks on busy days and less for days with lower attendance. Disneyland and Disney World are notorious for increasing their ticket prices on weekends and holidays to help push fans to visit the attractions on days with decreased demand.

The idea of dynamic pricing has recently caused an uproar amongst consumers. Fast-food chain Wendy’s (WEN) recently angered its customers last month after its CEO Kirk Tanner revealed during an earnings call in February that the company “will begin testing more enhanced features like dynamic pricing” as early as 2025.

Social media users called Wendy’s “greedy” for its plan to test out the change and even threatened to boycott its restaurants.

After facing backlash, Wendy’s later claimed in a statement that its CEO’s comments about dynamic pricing during the earnings call was “misconstrued.”

“This was misconstrued in some media reports as an intent to raise prices when demand is highest at our restaurants,” reads the statement. “We have no plans to do that and would not raise prices when our customers are visiting us most.”

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic covid-19 testing uk-

Spread & Containment2 weeks ago

Spread & Containment2 weeks agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International3 weeks ago

International3 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoParexel CEO to retire; CAR-T maker AffyImmune promotes business leader to chief executive

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

International3 weeks ago

International3 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoKey Events This Week: All Eyes On Core PCE Amid Deluge Of Fed Speakers

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoA Blue State Exodus: Who Can Afford To Be A Liberal