Government

Amazon’s union battle in Bessemer, Alabama is about dignity, racial justice, and the future of the American worker

This week, the historic unionization drive by Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Ala. will get an audience in the Capitol, as Amazon worker and union advocate Jennifer Bates testifies in front of the Senate Budget Committee. While the hearing will…

By Andre M. Perry, Molly Kinder, Laura Stateler, Carl Romer

This week, the historic unionization drive by Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Ala. will get an audience in the Capitol, as Amazon worker and union advocate Jennifer Bates testifies in front of the Senate Budget Committee. While the hearing will focus mainly on income inequality, the fight by Bates and her fellow Amazon workers for union representation in the majority-Black city of Bessemer is just as much about racial justice, basic dignity, and the right of workers to have a voice in their workplaces.

If the Bessemer workers vote to be represented by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) this month, they will become the first unionized Amazon warehouse in the country. It will also mark one of the biggest union victories in the South in decades, potentially galvanizing the labor movement and inspiring workers far beyond Alabama.

The Bessemer vote comes one year into a pandemic that has exacerbated the nation’s preexisting conditions of racism and rampant inequality. While the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan will bring immediate relief for low- and middle-income Americans, most of the provisions are temporary and do not address the structural causes of the current “K-shaped” recovery that sees many white Americans experiencing an economic rebound while Black and brown communities suffer higher rates of death, unemployment, and economic insecurity.

Society still needs to dismantle and replace the underlying structures that generate these racial disparities. And while tax cuts and stimulus checks provide needed relief, what can truly change the system is worker power.

Amazon has grown even more dominant and shared little of its pandemic profits with workers

Black workers are overrepresented among the risky essential jobs (like those at Amazon’s warehouses) on the COVID-19 frontlines, and especially among frontline jobs that pay less than a living wage. Black workers comprise 27% of Amazon’s workforce, compared to just 13% of workers overall in the U.S. In Amazon‘s Bessemer warehouse, union organizers estimate that 85% of workers are Black.

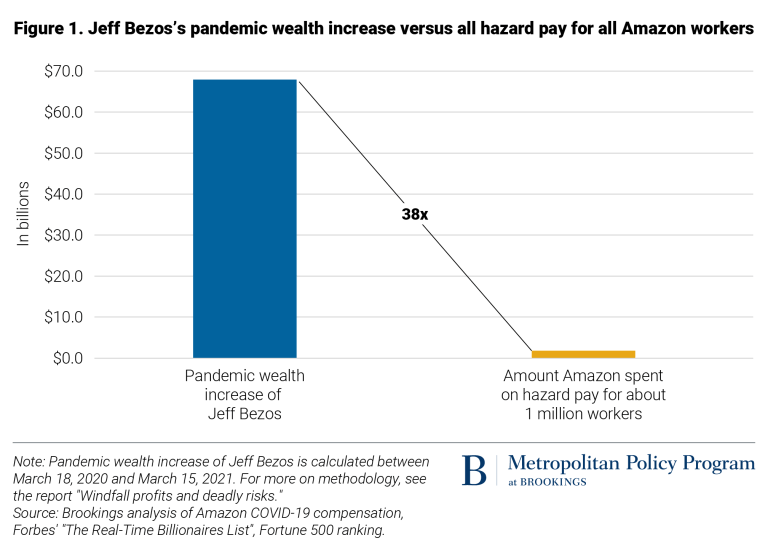

Amazon’s disproportionately Black workforce has risked their lives during the pandemic, but the company has shared little of its astonishing profits with them. Last year, Amazon earned an additional $9.7 billion in profit—a staggering 84% increase compared to 2019. The company’s stock price has risen 82%, while founder Jeff Bezos has added $67.9 billion to his wealth—38 times the total hazard pay Amazon has paid its 1 million workers since March.

Despite soaring profits, Amazon ended its $2 per hour pandemic wage increase last summer and replaced it with occasional bonuses. From March 2020 through the end of the year, Amazon’s frontline workers earned an average of $0.99 per hour of extra pay, or a roughly 7% pay increase. Amazon’s pandemic pay bump was less than half of the increased pay at competitor Costco, and a fraction of what it could have afforded from the extra profits it earned during—and largely because of—the pandemic. In fact, Amazon could have more than quintupled the hazard pay it gave its workers and still earned more profit than in 2019. And while Amazon frequently touts its $15 per hour starting wage, Costco’s recent increase of its starting wage to $16 per hour (despite having significantly smaller profits than Amazon) shows that $15 is a floor, not a ceiling.

A drive for dignity and racial justice seeks to defy the odds

Some of the workers at the Bessemer warehouse have called on Amazon to reinstate its $2 per hour hazard pay. Yet Amazon’s unwillingness to share its staggering profits with its workers is not the only—or even the primary—driver of the union effort in Bessemer.

In an essay published in The Guardian last month, labor journalist Steven Greenhouse introduced Darryl Richardson, a 51-year-old “picker” at the Bessemer warehouse. Richardson voiced his frustration about the dehumanizing nature of his work at Amazon, including the unrelenting pace, the risk of being terminated at any point, and the constant surveillance.

“You don’t get treated like a person,” Richardson said. “They work you like a robot…You don’t have time to leave your workstation to get water. You don’t have time to go to the bathroom.” As Amazon’s profits climb and its market dominance continues, workers like Richardson want a seat at the table to make their workplace humane.

Bessemer’s pro-union workers face an uphill battle as they take on one of the most powerful companies in the world. Amazon’s aggressive anti-union tactics have garnered headlines, but they are illustrative of the daunting challenges and uneven playing field facing organizing efforts in all workplaces. Today, 65% of Americans approve of labor unions—the highest level since 2003. But after decades of declining union participation, only about 10% of American workers are members of one.

Birmingham’s history shows that unions are key to a prosperous Black middle class

While the country’s decades-old labor laws make it extremely difficult for workers to form a union anywhere, the pervasive right-to-work laws in the South and conservative states make organizing efforts like the one in Bessemer even more difficult.

In the South, anti-labor laws are inextricably linked to the historic suppression of Black workers. Racism in the form of no- or low-wage Black labor has been part of the growth model of racialized capitalism. And when workers are unable to collectively bargain and demand their fair share, economic growth becomes concentrated in the hands of a few.

Fortunately, the Birmingham metropolitan area—home to Bessemer—has already proven that unionized Black workers can create economic growth and shared prosperity. At the turn of the 20th century, Birmingham labor unions facilitated the establishment of a Black middle class. Black and white miners organized to form the United Mine Workers (UMW) union and, together, secured better wages. Following UMW’s success, what was then known as the Alabama Federation of Labor (AFL) followed the same strategy of a racially integrated membership—in part out of fear that nonunionized Black workers would replace striking workers. As a result, Black Alabamians earned leadership positions and spots in every committee of the AFL, and the union’s first five vice presidents were Black. This inclusive labor movement continued until the 1930s, when U.S. Steel—rife with Ku Klux Klan members—began to restrict job promotions for unionized Black workers, limiting access to senior positions they previously occupied.

The Bessemer union battle comes after decades of concerted effort by business leaders and policymakers to beat back the 20th century victories of labor organizers. From Ronald Reagan’s breaking of the air traffic controllers’ strike to Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, these forces have eroded labor union protections, and with it, workers’ say in their workplaces.

Fixing the country’s broken labor laws to give workers like those in Bessemer a fighting chance will require major legislative change. Last week, the White House issued a statement backing the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act. The legislation would enable more workers to form a union, exert greater power in disputes, and exercise their right to strike, while curbing and penalizing employers’ retaliation and interference and limiting right-to-work laws. The PRO Act passed in the House of Representatives last week but faces long odds in the Senate due to strong Republican opposition and fierce resistance from business. Short of ending the filibuster, the act has little chance of passage.

Ultimately, change will require an empowered workforce demanding it. In the words of Frederick Douglass, “Power concedes nothing without a demand”—and that demand looks like Bessemer workers standing up to one of the most powerful companies the world has ever seen.

In order for these and other workers to have a chance, they will need allies in Congress to create a more level playing field. In 1935, the 74th Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act because of the labor movement. In 1964, the 88th Congress passed the Civil Rights Act because of the civil rights movement. Today, the 117th Congress needs similar pressure from the racial and economic justice movements. The workers in Bessemer are doing just that, which should inspire others across the nation to demand better working conditions, higher wages, and stronger labor laws from both their own management and leaders in Washington.

unemployment pandemic covid-19 stimulus economic growth white house congress senate house of representatives suppression recovery stimulusGovernment

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate…

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate iron levels in their blood due to a COVID-19 infection could be at greater risk of long COVID.

A new study indicates that problems with iron levels in the bloodstream likely trigger chronic inflammation and other conditions associated with the post-COVID phenomenon. The findings, published on March 1 in Nature Immunology, could offer new ways to treat or prevent the condition.

Long COVID Patients Have Low Iron Levels

Researchers at the University of Cambridge pinpointed low iron as a potential link to long-COVID symptoms thanks to a study they initiated shortly after the start of the pandemic. They recruited people who tested positive for the virus to provide blood samples for analysis over a year, which allowed the researchers to look for post-infection changes in the blood. The researchers looked at 214 samples and found that 45 percent of patients reported symptoms of long COVID that lasted between three and 10 months.

In analyzing the blood samples, the research team noticed that people experiencing long COVID had low iron levels, contributing to anemia and low red blood cell production, just two weeks after they were diagnosed with COVID-19. This was true for patients regardless of age, sex, or the initial severity of their infection.

According to one of the study co-authors, the removal of iron from the bloodstream is a natural process and defense mechanism of the body.

But it can jeopardize a person’s recovery.

“When the body has an infection, it responds by removing iron from the bloodstream. This protects us from potentially lethal bacteria that capture the iron in the bloodstream and grow rapidly. It’s an evolutionary response that redistributes iron in the body, and the blood plasma becomes an iron desert,” University of Oxford professor Hal Drakesmith said in a press release. “However, if this goes on for a long time, there is less iron for red blood cells, so oxygen is transported less efficiently affecting metabolism and energy production, and for white blood cells, which need iron to work properly. The protective mechanism ends up becoming a problem.”

The research team believes that consistently low iron levels could explain why individuals with long COVID continue to experience fatigue and difficulty exercising. As such, the researchers suggested iron supplementation to help regulate and prevent the often debilitating symptoms associated with long COVID.

“It isn’t necessarily the case that individuals don’t have enough iron in their body, it’s just that it’s trapped in the wrong place,” Aimee Hanson, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge who worked on the study, said in the press release. “What we need is a way to remobilize the iron and pull it back into the bloodstream, where it becomes more useful to the red blood cells.”

The research team pointed out that iron supplementation isn’t always straightforward. Achieving the right level of iron varies from person to person. Too much iron can cause stomach issues, ranging from constipation, nausea, and abdominal pain to gastritis and gastric lesions.

1 in 5 Still Affected by Long COVID

COVID-19 has affected nearly 40 percent of Americans, with one in five of those still suffering from symptoms of long COVID, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Long COVID is marked by health issues that continue at least four weeks after an individual was initially diagnosed with COVID-19. Symptoms can last for days, weeks, months, or years and may include fatigue, cough or chest pain, headache, brain fog, depression or anxiety, digestive issues, and joint or muscle pain.

Government

Walmart joins Costco in sharing key pricing news

The massive retailers have both shared information that some retailers keep very close to the vest.

As we head toward a presidential election, the presumed candidates for both parties will look for issues that rally undecided voters.

The economy will be a key issue, with Democrats pointing to job creation and lowering prices while Republicans will cite the layoffs at Big Tech companies, high housing prices, and of course, sticky inflation.

The covid pandemic created a perfect storm for inflation and higher prices. It became harder to get many items because people getting sick slowed down, or even stopped, production at some factories.

Related: Popular mall retailer shuts down abruptly after bankruptcy filing

It was also a period where demand increased while shipping, trucking and delivery systems were all strained or thrown out of whack. The combination led to product shortages and higher prices.

You might have gone to the grocery store and not been able to buy your favorite paper towel brand or find toilet paper at all. That happened partly because of the supply chain and partly due to increased demand, but at the end of the day, it led to higher prices, which some consumers blamed on President Joe Biden's administration.

Biden, of course, was blamed for the price increases, but as inflation has dropped and grocery prices have fallen, few companies have been up front about it. That's probably not a political choice in most cases. Instead, some companies have chosen to lower prices more slowly than they raised them.

However, two major retailers, Walmart (WMT) and Costco, have been very honest about inflation. Walmart Chief Executive Doug McMillon's most recent comments validate what Biden's administration has been saying about the state of the economy. And they contrast with the economic picture being painted by Republicans who support their presumptive nominee, Donald Trump.

Image source: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Walmart sees lower prices

McMillon does not talk about lower prices to make a political statement. He's communicating with customers and potential customers through the analysts who cover the company's quarterly-earnings calls.

During Walmart's fiscal-fourth-quarter-earnings call, McMillon was clear that prices are going down.

"I'm excited about the omnichannel net promoter score trends the team is driving. Across countries, we continue to see a customer that's resilient but looking for value. As always, we're working hard to deliver that for them, including through our rollbacks on food pricing in Walmart U.S. Those were up significantly in Q4 versus last year, following a big increase in Q3," he said.

He was specific about where the chain has seen prices go down.

"Our general merchandise prices are lower than a year ago and even two years ago in some categories, which means our customers are finding value in areas like apparel and hard lines," he said. "In food, prices are lower than a year ago in places like eggs, apples, and deli snacks, but higher in other places like asparagus and blackberries."

McMillon said that in other areas prices were still up but have been falling.

"Dry grocery and consumables categories like paper goods and cleaning supplies are up mid-single digits versus last year and high teens versus two years ago. Private-brand penetration is up in many of the countries where we operate, including the United States," he said.

Costco sees almost no inflation impact

McMillon avoided the word inflation in his comments. Costco (COST) Chief Financial Officer Richard Galanti, who steps down on March 15, has been very transparent on the topic.

The CFO commented on inflation during his company's fiscal-first-quarter-earnings call.

"Most recently, in the last fourth-quarter discussion, we had estimated that year-over-year inflation was in the 1% to 2% range. Our estimate for the quarter just ended, that inflation was in the 0% to 1% range," he said.

Galanti made clear that inflation (and even deflation) varied by category.

"A bigger deflation in some big and bulky items like furniture sets due to lower freight costs year over year, as well as on things like domestics, bulky lower-priced items, again, where the freight cost is significant. Some deflationary items were as much as 20% to 30% and, again, mostly freight-related," he added.

bankruptcy pandemic trumpGovernment

Walmart has really good news for shoppers (and Joe Biden)

The giant retailer joins Costco in making a statement that has political overtones, even if that’s not the intent.

As we head toward a presidential election, the presumed candidates for both parties will look for issues that rally undecided voters.

The economy will be a key issue, with Democrats pointing to job creation and lowering prices while Republicans will cite the layoffs at Big Tech companies, high housing prices, and of course, sticky inflation.

The covid pandemic created a perfect storm for inflation and higher prices. It became harder to get many items because people getting sick slowed down, or even stopped, production at some factories.

Related: Popular mall retailer shuts down abruptly after bankruptcy filing

It was also a period where demand increased while shipping, trucking and delivery systems were all strained or thrown out of whack. The combination led to product shortages and higher prices.

You might have gone to the grocery store and not been able to buy your favorite paper towel brand or find toilet paper at all. That happened partly because of the supply chain and partly due to increased demand, but at the end of the day, it led to higher prices, which some consumers blamed on President Joe Biden's administration.

Biden, of course, was blamed for the price increases, but as inflation has dropped and grocery prices have fallen, few companies have been up front about it. That's probably not a political choice in most cases. Instead, some companies have chosen to lower prices more slowly than they raised them.

However, two major retailers, Walmart (WMT) and Costco, have been very honest about inflation. Walmart Chief Executive Doug McMillon's most recent comments validate what Biden's administration has been saying about the state of the economy. And they contrast with the economic picture being painted by Republicans who support their presumptive nominee, Donald Trump.

Image source: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Walmart sees lower prices

McMillon does not talk about lower prices to make a political statement. He's communicating with customers and potential customers through the analysts who cover the company's quarterly-earnings calls.

During Walmart's fiscal-fourth-quarter-earnings call, McMillon was clear that prices are going down.

"I'm excited about the omnichannel net promoter score trends the team is driving. Across countries, we continue to see a customer that's resilient but looking for value. As always, we're working hard to deliver that for them, including through our rollbacks on food pricing in Walmart U.S. Those were up significantly in Q4 versus last year, following a big increase in Q3," he said.

He was specific about where the chain has seen prices go down.

"Our general merchandise prices are lower than a year ago and even two years ago in some categories, which means our customers are finding value in areas like apparel and hard lines," he said. "In food, prices are lower than a year ago in places like eggs, apples, and deli snacks, but higher in other places like asparagus and blackberries."

McMillon said that in other areas prices were still up but have been falling.

"Dry grocery and consumables categories like paper goods and cleaning supplies are up mid-single digits versus last year and high teens versus two years ago. Private-brand penetration is up in many of the countries where we operate, including the United States," he said.

Costco sees almost no inflation impact

McMillon avoided the word inflation in his comments. Costco (COST) Chief Financial Officer Richard Galanti, who steps down on March 15, has been very transparent on the topic.

The CFO commented on inflation during his company's fiscal-first-quarter-earnings call.

"Most recently, in the last fourth-quarter discussion, we had estimated that year-over-year inflation was in the 1% to 2% range. Our estimate for the quarter just ended, that inflation was in the 0% to 1% range," he said.

Galanti made clear that inflation (and even deflation) varied by category.

"A bigger deflation in some big and bulky items like furniture sets due to lower freight costs year over year, as well as on things like domestics, bulky lower-priced items, again, where the freight cost is significant. Some deflationary items were as much as 20% to 30% and, again, mostly freight-related," he added.

bankruptcy pandemic trump-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges