Government

World economy in 2022: the big factors to watch closely

Will we now see a proper pandemic recovery?

Will 2022 be the year where the world economy recovers from the pandemic? That’s the big question on everyone’s lips as the festive break comes to an end.

One complicating factor is that most of the latest major forecasts were published in the weeks before the omicron variant swept the world. At that time, the mood was that recovery was indeed around the corner, with the IMF projecting 4.9% growth in 2022 and the OECD projecting 4.5%. These numbers are lower than the circa 5% to 6% global growth expected to have been achieved in 2021, but that represents the inevitable rebound from reopening after the pandemic lows of 2020.

So what difference will omicron make to the state of the economy? We already know that it had an effect in the run-up to Christmas, with for example UK hospitality taking a hit as people stayed away from restaurants. For the coming months, the combination of raised restrictions, cautious consumers and people taking time off sick is likely to take its toll.

Yet the fact that the new variant seems milder than originally feared is likely to mean that restrictions are lifted more quickly and that the economic effect is more moderate than it might have been. Israel and Australia, for example, are already loosening restrictions despite high case numbers. At the same time, however, until the west tackles very low vaccination rates in some parts of the world, don’t be surprised if another new variant brings further damage to both public health and the world economy.

As things stand, the UK thinktank the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) published a more recent 2022 forecast just before Christmas. It predicted that global growth would reach 4% this year, and that the total world economy would hit a new all-time high of US$100 trillion (£74 trillion).

The inflation question

One other big unknown is inflation. In 2021 we saw a sudden and sharp surge in inflation resulting from the restoration of global economic activity and bottlenecks in the global supply chain. There has been much debate about whether this inflation will prove temporary, and central banks have been coming under pressure to ensure it doesn’t spiral.

So far, the European Central Bank, Federal Reserve and Bank of Japan have all abstained from raising interest rates from their very low levels. The Bank of England, on the other hand, followed the IMF’s advice and raised rates from 0.1% to 0.25% in December. This is too little to curb inflation or do any good besides increase the cost of borrowing for firms and to raise mortgage payments for households. That said, the markets are betting that more UK rate rises will follow, and that the Fed will also start raising rates in the spring.

Yet the more important question regarding inflation is what happens to quantitative easing (QE). This is the policy of increasing the money supply that has seen the major central banks buying some US$25 trillion in government bonds and other financial assets in recent years, including about US$9 trillion on the back of COVID.

Both the Fed and ECB are still operating QE and adding assets to their balance sheets every month. The Fed is currently tapering the rate of these purchases with a view to stopping them in March, having recently announced that it would bring forward the end date from June. The ECB has also said it will scale back QE, but is committed to continuing for the time being.

Of course, the real question is what these central banks do in practice. Ending QE and raising interest rates will undoubtedly hamper the recovery – the CEBR forecast, for example, assumes that it will see bond, stock and property markets falling by 10% to 25% in 2022. It will be interesting to see whether the prospect of such upheaval forces the Fed and Bank of England to get more dovish again – particularly when you factor in the continued uncertainty around COVID.

Politics and global trade

The trade war between the US and China looks likely to continue in 2022. The “phase 1” deal between the two nations, in which China had agreed to increase its purchases of certain US goods and services by a combined US$200 billion over 2020 and 2021 has missed its target by about 40% (as at the end of November).

The deal has now expired, and the big question for international trade in 2022 is whether there will be a new “phase 2” deal. It is hard to feel particularly optimistic here: Donald Trump may have long since left office, but US strategy on China remains distinctly Trumpian, with no notable concessions having been offered to the Chinese under Joe Biden.

Elsewhere, western tensions with Russia over Ukraine and further escalation of economic sanctions against Putin may have economic consequences for the global economy – not least because of Europe’s dependency on Russian gas. The more engagement that we see on both fronts in the coming months, the better it will be for growth.

Whatever happens politically, it is clear that Asia will be very important for growth prospects in 2022. Major economies such as the UK, Japan and the eurozone were all still smaller than before the pandemic as recently as the third quarter of 2021, the latest data available. The only major developed economy that has already recovered its losses and regained its pre-COVID size is the United States.

Economic growth by country since 2015

On the other hand, China has managed the pandemic well – albeit with strict control measures – and its economy has achieved strong growth since the second quarter of 2020. It has been struggling with a heavily over-indebted property market, but appears to have handled these problems relatively smoothly. Though the jury is out on the extent to which China’s debt problems will be a drag in 2022, some such as Morgan Stanley argue that strong exports, accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, relief for real estate sector and a slightly more relaxed approach to carbon reduction point to a decent performance.

As for India, whose economy has seen double dips during the pandemic, it is showing a strong positive trend with 8.5% expected growth in the year ahead. I therefore suspect that emerging Asia will shoulder global growth in 2022, and the world’s economic centre of gravity will continue to shift eastwards at an accelerated pace.

Muhammad Ali Nasir does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

economic growth reopening global growth pandemic bonds government bonds qe fed federal reserve real estate trump recovery global trade interest rates india japan european europe uk russia ukraine chinaGovernment

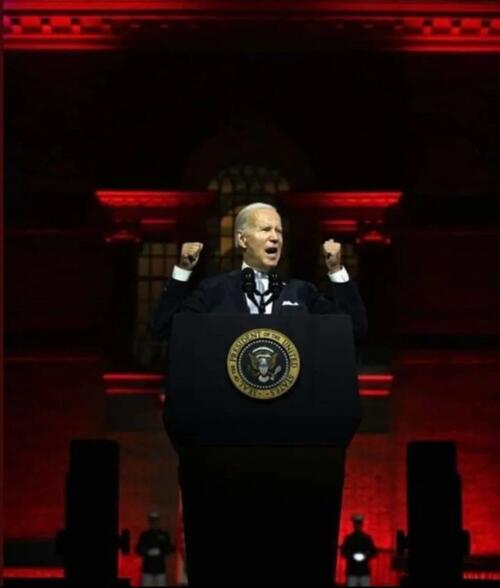

President Biden Delivers The “Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President”

President Biden Delivers The "Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President"

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through…

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through the State of The Union, President Biden can go back to his crypt now.

Whatever 'they' gave Biden, every American man, woman, and the other should be allowed to take it - though it seems the cocktail brings out 'dark Brandon'?

Tl;dw: Biden's Speech tonight ...

-

Fund Ukraine.

-

Trump is threat to democracy and America itself.

-

Abortion is good.

-

American Economy is stronger than ever.

-

Inflation wasn't Biden's fault.

-

Illegals are Americans too.

-

Republicans are responsible for the border crisis.

-

Trump is bad.

-

Biden stands with trans-children.

-

J6 was the worst insurrection since the Civil War.

(h/t @TCDMS99)

Tucker Carlson's response sums it all up perfectly:

"that was possibly the darkest, most un-American speech given by an American president. It wasn't a speech, it was a rant..."

Carlson continued: "The true measure of a nation's greatness lies within its capacity to control borders, yet Bid refuses to do it."

"In a fair election, Joe Biden cannot win"

And concluded:

“There was not a meaningful word for the entire duration about the things that actually matter to people who live here.”

Victor Davis Hanson added some excellent color, but this was probably the best line on Biden:

"he doesn't care... he lives in an alternative reality."

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 8, 2024

* * *

Watch SOTU Live here...

* * *

Mises' Connor O'Keeffe, warns: "Be on the Lookout for These Lies in Biden's State of the Union Address."

On Thursday evening, President Joe Biden is set to give his third State of the Union address. The political press has been buzzing with speculation over what the president will say. That speculation, however, is focused more on how Biden will perform, and which issues he will prioritize. Much of the speech is expected to be familiar.

The story Biden will tell about what he has done as president and where the country finds itself as a result will be the same dishonest story he's been telling since at least the summer.

He'll cite government statistics to say the economy is growing, unemployment is low, and inflation is down.

Something that has been frustrating Biden, his team, and his allies in the media is that the American people do not feel as economically well off as the official data says they are. Despite what the White House and establishment-friendly journalists say, the problem lies with the data, not the American people's ability to perceive their own well-being.

As I wrote back in January, the reason for the discrepancy is the lack of distinction made between private economic activity and government spending in the most frequently cited economic indicators. There is an important difference between the two:

-

Government, unlike any other entity in the economy, can simply take money and resources from others to spend on things and hire people. Whether or not the spending brings people value is irrelevant

-

It's the private sector that's responsible for producing goods and services that actually meet people's needs and wants. So, the private components of the economy have the most significant effect on people's economic well-being.

Recently, government spending and hiring has accounted for a larger than normal share of both economic activity and employment. This means the government is propping up these traditional measures, making the economy appear better than it actually is. Also, many of the jobs Biden and his allies take credit for creating will quickly go away once it becomes clear that consumers don't actually want whatever the government encouraged these companies to produce.

On top of all that, the administration is dealing with the consequences of their chosen inflation rhetoric.

Since its peak in the summer of 2022, the president's team has talked about inflation "coming back down," which can easily give the impression that it's prices that will eventually come back down.

But that's not what that phrase means. It would be more honest to say that price increases are slowing down.

Americans are finally waking up to the fact that the cost of living will not return to prepandemic levels, and they're not happy about it.

The president has made some clumsy attempts at damage control, such as a Super Bowl Sunday video attacking food companies for "shrinkflation"—selling smaller portions at the same price instead of simply raising prices.

In his speech Thursday, Biden is expected to play up his desire to crack down on the "corporate greed" he's blaming for high prices.

In the name of "bringing down costs for Americans," the administration wants to implement targeted price ceilings - something anyone who has taken even a single economics class could tell you does more harm than good. Biden would never place the blame for the dramatic price increases we've experienced during his term where it actually belongs—on all the government spending that he and President Donald Trump oversaw during the pandemic, funded by the creation of $6 trillion out of thin air - because that kind of spending is precisely what he hopes to kick back up in a second term.

If reelected, the president wants to "revive" parts of his so-called Build Back Better agenda, which he tried and failed to pass in his first year. That would bring a significant expansion of domestic spending. And Biden remains committed to the idea that Americans must be forced to continue funding the war in Ukraine. That's another topic Biden is expected to highlight in the State of the Union, likely accompanied by the lie that Ukraine spending is good for the American economy. It isn't.

It's not possible to predict all the ways President Biden will exaggerate, mislead, and outright lie in his speech on Thursday. But we can be sure of two things. The "state of the Union" is not as strong as Biden will say it is. And his policy ambitions risk making it much worse.

* * *

The American people will be tuning in on their smartphones, laptops, and televisions on Thursday evening to see if 'sloppy joe' 81-year-old President Joe Biden can coherently put together more than two sentences (even with a teleprompter) as he gives his third State of the Union in front of a divided Congress.

President Biden will speak on various topics to convince voters why he shouldn't be sent to a retirement home.

The state of our union under President Biden: three years of decline. pic.twitter.com/Da1KOIb3eR

— Speaker Mike Johnson (@SpeakerJohnson) March 7, 2024

According to CNN sources, here are some of the topics Biden will discuss tonight:

Economic issues: Biden and his team have been drafting a speech heavy on economic populism, aides said, with calls for higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy – an attempt to draw a sharp contrast with Republicans and their likely presidential nominee, Donald Trump.

Health care expenses: Biden will also push for lowering health care costs and discuss his efforts to go after drug manufacturers to lower the cost of prescription medications — all issues his advisers believe can help buoy what have been sagging economic approval ratings.

Israel's war with Hamas: Also looming large over Biden's primetime address is the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, which has consumed much of the president's time and attention over the past few months. The president's top national security advisers have been working around the clock to try to finalize a ceasefire-hostages release deal by Ramadan, the Muslim holy month that begins next week.

An argument for reelection: Aides view Thursday's speech as a critical opportunity for the president to tout his accomplishments in office and lay out his plans for another four years in the nation's top job. Even though viewership has declined over the years, the yearly speech reliably draws tens of millions of households.

Sources provided more color on Biden's SOTU address:

The speech is expected to be heavy on economic populism. The president will talk about raising taxes on corporations and the wealthy. He'll highlight efforts to cut costs for the American people, including pushing Congress to help make prescription drugs more affordable.

Biden will talk about the need to preserve democracy and freedom, a cornerstone of his re-election bid. That includes protecting and bolstering reproductive rights, an issue Democrats believe will energize voters in November. Biden is also expected to promote his unity agenda, a key feature of each of his addresses to Congress while in office.

Biden is also expected to give remarks on border security while the invasion of illegals has become one of the most heated topics among American voters. A majority of voters are frustrated with radical progressives in the White House facilitating the illegal migrant invasion.

It is probable that the president will attribute the failure of the Senate border bill to the Republicans, a claim many voters view as unfounded. This is because the White House has the option to issue an executive order to restore border security, yet opts not to do so

Maybe this is why?

Most Americans are still unaware that the census counts ALL people, including illegal immigrants, for deciding how many House seats each state gets!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 7, 2024

This results in Dem states getting roughly 20 more House seats, which is another strong incentive for them not to deport illegals.

While Biden addresses the nation, the Biden administration will be armed with a social media team to pump propaganda to at least 100 million Americans.

"The White House hosted about 70 creators, digital publishers, and influencers across three separate events" on Wednesday and Thursday, a White House official told CNN.

Not a very capable social media team...

The State of Confusion https://t.co/C31mHc5ABJ

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) March 7, 2024

The administration's move to ramp up social media operations comes as users on X are mostly free from government censorship with Elon Musk at the helm. This infuriates Democrats, who can no longer censor their political enemies on X.

Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers tell Axios that the president's SOTU performance will be critical as he tries to dispel voter concerns about his elderly age. The address reached as many as 27 million people in 2023.

"We are all nervous," said one House Democrat, citing concerns about the president's "ability to speak without blowing things."

The SOTU address comes as Biden's polling data is in the dumps.

BetOnline has created several money-making opportunities for gamblers tonight, such as betting on what word Biden mentions the most.

As well as...

We will update you when Tucker Carlson's live feed of SOTU is published.

Fuck it. We’ll do it live! Thursday night, March 7, our live response to Joe Biden’s State of the Union speech. pic.twitter.com/V0UwOrgKvz

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 6, 2024

International

What is intersectionality and why does it make feminism more effective?

The social categories that we belong to shape our understanding of the world in different ways.

The way we talk about society and the people and structures in it is constantly changing. One term you may come across this International Women’s Day is “intersectionality”. And specifically, the concept of “intersectional feminism”.

Intersectionality refers to the fact that everyone is part of multiple social categories. These include gender, social class, sexuality, (dis)ability and racialisation (when people are divided into “racial” groups often based on skin colour or features).

These categories are not independent of each other, they intersect. This looks different for every person. For example, a black woman without a disability will have a different experience of society than a white woman without a disability – or a black woman with a disability.

An intersectional approach makes social policy more inclusive and just. Its value was evident in research during the pandemic, when it became clear that women from various groups, those who worked in caring jobs and who lived in crowded circumstances were much more likely to die from COVID.

A long-fought battle

American civil rights leader and scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw first introduced the term intersectionality in a 1989 paper. She argued that focusing on a single form of oppression (such as gender or race) perpetuated discrimination against black women, who are simultaneously subjected to both racism and sexism.

Crenshaw gave a name to ways of thinking and theorising that black and Latina feminists, as well as working-class and lesbian feminists, had argued for decades. The Combahee River Collective of black lesbians was groundbreaking in this work.

They called for strategic alliances with black men to oppose racism, white women to oppose sexism and lesbians to oppose homophobia. This was an example of how an intersectional understanding of identity and social power relations can create more opportunities for action.

These ideas have, through political struggle, come to be accepted in feminist thinking and women’s studies scholarship. An increasing number of feminists now use the term “intersectional feminism”.

The term has moved from academia to feminist activist and social justice circles and beyond in recent years. Its popularity and widespread use means it is subjected to much scrutiny and debate about how and when it should be employed. For example, some argue that it should always include attention to racism and racialisation.

Recognising more issues makes feminism more effective

In writing about intersectionality, Crenshaw argued that singular approaches to social categories made black women’s oppression invisible. Many black feminists have pointed out that white feminists frequently overlook how racial categories shape different women’s experiences.

One example is hair discrimination. It is only in the 2020s that many organisations in South Africa, the UK and US have recognised that it is discriminatory to regulate black women’s hairstyles in ways that render their natural hair unacceptable.

This is an intersectional approach. White women and most black men do not face the same discrimination and pressures to straighten their hair.

“Abortion on demand” in the 1970s and 1980s in the UK and USA took no account of the fact that black women in these and many other countries needed to campaign against being given abortions against their will. The fight for reproductive justice does not look the same for all women.

Similarly, the experiences of working-class women have frequently been rendered invisible in white, middle class feminist campaigns and writings. Intersectionality means that these issues are recognised and fought for in an inclusive and more powerful way.

In the 35 years since Crenshaw coined the term, feminist scholars have analysed how women are positioned in society, for example, as black, working-class, lesbian or colonial subjects. Intersectionality reminds us that fruitful discussions about discrimination and justice must acknowledge how these different categories affect each other and their associated power relations.

This does not mean that research and policy cannot focus predominantly on one social category, such as race, gender or social class. But it does mean that we cannot, and should not, understand those categories in isolation of each other.

Ann Phoenix does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

africa uk pandemicInternational

Biden defends immigration policy during State of the Union, blaming Republicans in Congress for refusing to act

A rising number of Americans say that immigration is the country’s biggest problem. Biden called for Congress to pass a bipartisan border and immigration…

President Joe Biden delivered the annual State of the Union address on March 7, 2024, casting a wide net on a range of major themes – the economy, abortion rights, threats to democracy, the wars in Gaza and Ukraine – that are preoccupying many Americans heading into the November presidential election.

The president also addressed massive increases in immigration at the southern border and the political battle in Congress over how to manage it. “We can fight about the border, or we can fix it. I’m ready to fix it,” Biden said.

But while Biden stressed that he wants to overcome political division and take action on immigration and the border, he cautioned that he will not “demonize immigrants,” as he said his predecessor, former President Donald Trump, does.

“I will not separate families. I will not ban people from America because of their faith,” Biden said.

Biden’s speech comes as a rising number of American voters say that immigration is the country’s biggest problem.

Immigration law scholar Jean Lantz Reisz answers four questions about why immigration has become a top issue for Americans, and the limits of presidential power when it comes to immigration and border security.

1. What is driving all of the attention and concern immigration is receiving?

The unprecedented number of undocumented migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border right now has drawn national concern to the U.S. immigration system and the president’s enforcement policies at the border.

Border security has always been part of the immigration debate about how to stop unlawful immigration.

But in this election, the immigration debate is also fueled by images of large groups of migrants crossing a river and crawling through barbed wire fences. There is also news of standoffs between Texas law enforcement and U.S. Border Patrol agents and cities like New York and Chicago struggling to handle the influx of arriving migrants.

Republicans blame Biden for not taking action on what they say is an “invasion” at the U.S. border. Democrats blame Republicans for refusing to pass laws that would give the president the power to stop the flow of migration at the border.

2. Are Biden’s immigration policies effective?

Confusion about immigration laws may be the reason people believe that Biden is not implementing effective policies at the border.

The U.S. passed a law in 1952 that gives any person arriving at the border or inside the U.S. the right to apply for asylum and the right to legally stay in the country, even if that person crossed the border illegally. That law has not changed.

Courts struck down many of former President Donald Trump’s policies that tried to limit immigration. Trump was able to lawfully deport migrants at the border without processing their asylum claims during the COVID-19 pandemic under a public health law called Title 42. Biden continued that policy until the legal justification for Title 42 – meaning the public health emergency – ended in 2023.

Republicans falsely attribute the surge in undocumented migration to the U.S. over the past three years to something they call Biden’s “open border” policy. There is no such policy.

Multiple factors are driving increased migration to the U.S.

More people are leaving dangerous or difficult situations in their countries, and some people have waited to migrate until after the COVID-19 pandemic ended. People who smuggle migrants are also spreading misinformation to migrants about the ability to enter and stay in the U.S.

3. How much power does the president have over immigration?

The president’s power regarding immigration is limited to enforcing existing immigration laws. But the president has broad authority over how to enforce those laws.

For example, the president can place every single immigrant unlawfully present in the U.S. in deportation proceedings. Because there is not enough money or employees at federal agencies and courts to accomplish that, the president will usually choose to prioritize the deportation of certain immigrants, like those who have committed serious and violent crimes in the U.S.

The federal agency Immigration and Customs Enforcement deported more than 142,000 immigrants from October 2022 through September 2023, double the number of people it deported the previous fiscal year.

But under current law, the president does not have the power to summarily expel migrants who say they are afraid of returning to their country. The law requires the president to process their claims for asylum.

Biden’s ability to enforce immigration law also depends on a budget approved by Congress. Without congressional approval, the president cannot spend money to build a wall, increase immigration detention facilities’ capacity or send more Border Patrol agents to process undocumented migrants entering the country.

4. How could Biden address the current immigration problems in this country?

In early 2024, Republicans in the Senate refused to pass a bill – developed by a bipartisan team of legislators – that would have made it harder to get asylum and given Biden the power to stop taking asylum applications when migrant crossings reached a certain number.

During his speech, Biden called this bill the “toughest set of border security reforms we’ve ever seen in this country.”

That bill would have also provided more federal money to help immigration agencies and courts quickly review more asylum claims and expedite the asylum process, which remains backlogged with millions of cases, Biden said. Biden said the bipartisan deal would also hire 1,500 more border security agents and officers, as well as 4,300 more asylum officers.

Removing this backlog in immigration courts could mean that some undocumented migrants, who now might wait six to eight years for an asylum hearing, would instead only wait six weeks, Biden said. That means it would be “highly unlikely” migrants would pay a large amount to be smuggled into the country, only to be “kicked out quickly,” Biden said.

“My Republican friends, you owe it to the American people to get this bill done. We need to act,” Biden said.

Biden’s remarks calling for Congress to pass the bill drew jeers from some in the audience. Biden quickly responded, saying that it was a bipartisan effort: “What are you against?” he asked.

Biden is now considering using section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act to get more control over immigration. This sweeping law allows the president to temporarily suspend or restrict the entry of all foreigners if their arrival is detrimental to the U.S.

This obscure law gained attention when Trump used it in January 2017 to implement a travel ban on foreigners from mainly Muslim countries. The Supreme Court upheld the travel ban in 2018.

Trump again also signed an executive order in April 2020 that blocked foreigners who were seeking lawful permanent residency from entering the country for 60 days, citing this same section of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Biden did not mention any possible use of section 212(f) during his State of the Union speech. If the president uses this, it would likely be challenged in court. It is not clear that 212(f) would apply to people already in the U.S., and it conflicts with existing asylum law that gives people within the U.S. the right to seek asylum.

Jean Lantz Reisz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

congress senate trump pandemic covid-19 mexico ukraine-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges