Uncategorized

Why Do Forecasters Disagree about Their Monetary Policy Expectations?

While forecasters generally disagree about the expected path of monetary policy, the level of disagreement as measured in the New York Fed’s Survey…

While forecasters generally disagree about the expected path of monetary policy, the level of disagreement as measured in the New York Fed’s Survey of Primary Dealers (SPD) has increased substantially since 2022. For instance, the dispersion of expectations about the future path of the target federal funds rate (FFR) has widened significantly. What explains the current elevated disagreement in FFR forecasts?

One possible reason is that dealers’ policy rate forecasts are based on projections for other variables, such as inflation and unemployment, and their expectations for those variables have diverged. Another possibility is that the disagreement is about the way in which those macroeconomic variables affect the policy rate—the perceived “reaction function” of the policymaker. In this post, we investigate which is a better description of the data. Our results point toward the former explanation: Allowing macroeconomic outlooks to vary across SPD respondents, while keeping the coefficients of the perceived reaction function constant, is better at accounting for the widened cross section of policy rate forecasts.

Disagreement about the Future Path of Monetary Policy Has Increased

The dispersion of dealers’ expectations about the future path of the policy rate has widened substantially in recent surveys. The left panel of the chart below shows the level and range of expectations for the target FFR seven to nine quarters ahead, using data from the SPD. The blue solid line is the median FFR expectation across respondents, and the shaded areas illustrate the distance between the 90th and 10th percentiles. While dispersion fell during the pandemic in 2020-21, as dealers expected close-to-zero policy rates for some time, since 2022 it has increased to over 2 percentage points, the most in ten years.

Dispersion of Expectations Has Widened

Sources: Authors’ calculations; Survey of Primary Dealers.

Notes: The left panel reports the median (line) and 90th-10th percentile range (shaded area) across survey respondents of the modal policy rate expectation seven, eight, or nine quarters ahead, by survey date. The data are from the Survey of Primary Dealers spanning the period July 2014–June 2023. FFR is federal funds rate. The right panel reports the mean distance between the 90th and 10th percentiles, by number of quarters ahead, for the full sample (shaded area) and for the recent sample (black lines).

The right panel of the chart highlights the level of disagreement relative to its historical norm, and shows that over the past year it has been pronounced across multiple horizons. For expectations eight quarters ahead collected since July 2022, the 90th and 10th percentiles have been on average 3.5 percentage points apart, or more than twice the distance in the historical sample.

Disentangling Differences in Economic Outlooks vs. Perceptions of Monetary Policy Rules

In our analysis, we assume that survey respondents implicitly use a Taylor rule in forming policy rate expectations. In essence, we posit that the expected policy rate for a given horizon is equal to the sum of its long-run expected value and the contributions of core PCE (personal consumption expenditures) inflation and unemployment, for that same horizon, weighted by their respective reaction function parameters. We re-estimate the reaction function parameters over time, allowing for changes in respondents’ perceptions, but those parameters are assumed to be uniform across horizons (three to twelve quarters ahead) within a survey sample. To strike a balance between time variation and sample size, we use rolling samples that include three surveys each.

Our approach follows a vast academic literature that employs linear regressions to estimate Taylor rule–like monetary policy rules; see, for instance, Bernanke (2015), Carvalho and Nechio (2014), and Bauer, Pflueger, and Sunderam (2022). It’s important to note that, because of the inherent codependence of expected policy rates and expected macroeconomic outlooks, linear regression estimates should be interpreted as the co-movement perceived by forecasters between the policy rate and the macroeconomic variables considered, rather than as causal relationships. That said, despite the endogeneity problem, Carvalho, Nechio, and Tristão (2021) find support for using ordinary regressions.

To gauge whether differing macroeconomic outlooks or policy rule perceptions better account for the observed dispersion in FFR expectations, we conduct two empirical experiments.

Experiment #1: Common Policy Rules, Varying Economic Outlooks (CR-VO): We estimate the common set of Taylor rule parameters that best fits the panel data (the pooled estimation), and then we use the dealer-specific expectations for inflation and unemployment (including the individual long-run expectations) to predict policy rate expectations. This experiment answers the counterfactual question: What would the cross section of dealers’ expectations be if they all used the same Taylor rule parameters but not the same macroeconomic outlooks?

Experiment #2: Varying Policy Rules, Common Economic Outlooks (VR-CO): We estimate the set of Taylor rule parameters that best fits each individual dealer’s data, and then, holding those estimated individual policy rule parameters constant, we impose common (median) expectations for inflation and unemployment across respondents. This experiment answers the counterfactual question: What would dealers’ expectations be if they all agreed on their macro expectations but had different views about the policy rule?

The closest precedent to these experiments is Carlstrom and Jacobson (2015), although their analysis relies on data from the Survey of Professional Forecasters from 1995-2008.

Dealers Agree on the Policy Rule, Disagree on the Economic Outlook

Since we are especially interested in the recent increase in disagreement, we focus on the forecasts for year-end 2023 and 2024, as reported by surveys conducted since July 2020. We show year-end 2024 forecasts in the chart below. In both panels, the red solid line and shaded region show the observed median expectations and the 90th–10th percentile band. The blue solid line and shaded areas show the corresponding percentiles for the two experiments.

CR-VO Experiment Better Matches Actual Forecast Distributions

Sources: Authors’ calculations; Survey of Primary Dealers.

Note: The panels show the actual and predicted distributions (10th, 50th, 90th percentiles) under the assumptions of constant parameters and varying outlooks (CR-VO) across survey respondents, versus constant outlooks and varying parameters (VR-CO), for year-end 2024.

The chart illustrates the central findings. The dispersion of policy rate expectations implied by experiment CR-VO better overlaps with the dispersion of actual forecasts. The dispersion of expectations implied by experiment VR-CO, on the other hand, is in general much larger than the dispersion of observed expectations. Thus, the counterfactual scenario in which dealers hold a common view about the policymaker’s reaction function but disagree on the economic outlook fits the observed data better than the alternative. We observe a similar pattern when looking at year-end 2023 forecasts.

To some extent, this finding is not surprising, as dealer-specific reaction function parameters are estimated from small samples and therefore one would expect the cross-sectional dispersion to be wide. However, the expectations fitted by experiment VR-CO are unable to match the increased disagreement that we observe in actual expectations in recent times.

Consider again the chart above: while the actual 90th–10th percentile range of the policy rate increases from 1 percentage point to 2.4 percentage points between January 2022 and December 2022 (when peak disagreement is reached), disagreement assuming uniform macro outlooks (and varying reaction function parameters) increases marginally, from 3.5 percentage points to 3.7 percentage points, while disagreement assuming uniform reaction parameters (and varying outlooks) rises from 1 percentage point to 1.6 percentage points.

To quantify the relative fit of the common policy rule versus common economic outlook explanations, the chart below shows the mean absolute error (MAE) of experiments CR-VO and VR-CO, pooled across respondents and horizons, for each survey.

Mean Absolute Error Is Lower for CR-VO Experiment

Sources: Authors’ calculations; Survey of Primary Dealers.

Notes: The chart reports the mean absolute error between actual forecasts and the fitted forecasts, for each survey date, produced assuming common coefficients and varying outlooks (CR-VO) and assuming varying coefficients and common outlooks (VR-CO). The y-axis is in logarithmic scale.

A lower MAE implies a better-fitting model, which is the case for the series computed for the experiment with common policy rules and varying outlooks for every survey in our sample. The average errors produced by experiment CR-VO are smaller than those for VR-CO by a large margin (notice the log scale). In recent months, the relative and absolute MAEs of the two experiments are roughly within the historical norm. In addition, note that both series increase during periods associated with policy uncertainty: the start of the 2020 pandemic and in the recent period of elevated inflation. However, the swings in the MAE implied by the common-outlooks experiment are larger.

Conclusion

Dealers’ expectations for the monetary policy path have diverged in recent times. Given uncertainty about how the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) would respond to a historically rare combination of persistently high inflation and low unemployment, one might expect dealers’ disagreement to stem at least in part from divergent views on the Federal Reserve’s reaction function. We find, however, that it is the economic outlook that accounts for the lion’s share of the increased disagreement.

At the time the research in this post was conducted, Arunima Sinha was an associate professor of economics at Fordham University and a visiting scholar in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Giorgio Topa is an economic research advisor in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Francisco Torralba is a policy and market analysis principal in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

How to cite this post:

Arunima Sinha, Giorgio Topa, and Francisco Torralba, “Why Do Forecasters Disagree about Their Monetary Policy Expectations?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, August 2, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/08/why-do-forecasters-disagree-about-their-monetary-policy-expectations/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Uncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

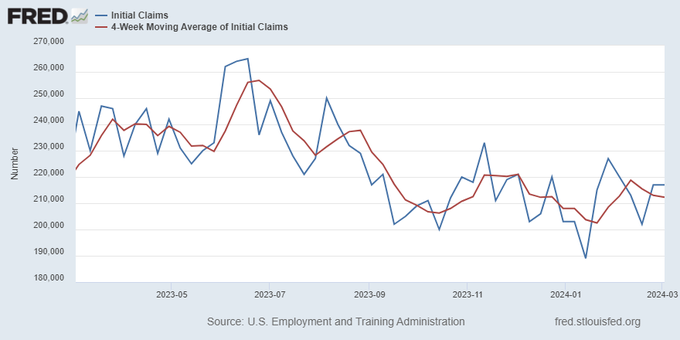

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

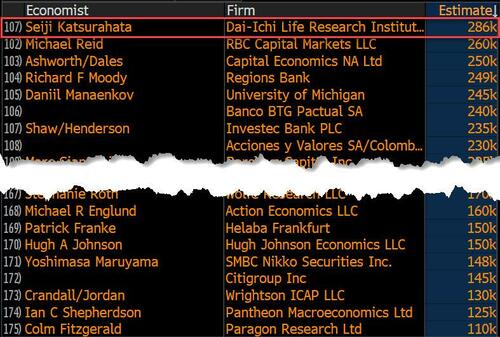

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

Uncategorized

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives…

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives floating around corporate media platforms has been the argument that the American people “just don’t seem to understand how good the economy really is right now.” If only they would look at the stats, they would realize that we are in the middle of a financial renaissance, right? It must be that people have been brainwashed by negative press from conservative sources…

I have to laugh at this notion because it’s a very common one throughout history – it’s an assertion made by almost every single political regime right before a major collapse. These people always say the same things, and when you study economics as long as I have you can’t help but throw up your hands and marvel at their dedication to the propaganda.

One example that comes to mind immediately is the delusional optimism of the “roaring” 1920s and the lead up to the Great Depression. At the time around 60% of the U.S. population was living in poverty conditions (according to the metrics of the decade) earning less than $2000 a year. However, in the years after WWI ravaged Europe, America’s economic power was considered unrivaled.

The 1920s was an era of mass production and rampant consumerism but it was all fueled by easy access to debt, a condition which had not really existed before in America. It was this illusion of prosperity created by the unchecked application of credit that eventually led to the massive stock market bubble and the crash of 1929. This implosion, along with the Federal Reserve’s policy of raising interest rates into economic weakness, created a black hole in the U.S. financial system for over a decade.

There are two primary tools that various failing regimes will often use to distort the true conditions of the economy: Debt and inflation. In the case of America today, we are experiencing BOTH problems simultaneously and this has made certain economic indicators appear healthy when they are, in fact, highly unstable. The average American knows this is the case because they see the effects everyday. They see the damage to their wallets, to their buying power, in the jobs market and in their quality of life. This is why public faith in the economy has been stuck in the dregs since 2021.

The establishment can flash out-of-context stats in people’s faces, but they can’t force the populace to see a recovery that simply does not exist. Let’s go through a short list of the most faulty indicators and the real reasons why the fiscal picture is not a rosy as the media would like us to believe…

The “miracle” labor market recovery

In the case of the U.S. labor market, we have a clear example of distortion through inflation. The $8 trillion+ dropped on the economy in the first 18 months of the pandemic response sent the system over the edge into stagflation land. Helicopter money has a habit of doing two things very well: Blowing up a bubble in stock markets and blowing up a bubble in retail. Hence, the massive rush by Americans to go out and buy, followed by the sudden labor shortage and the race to hire (mostly for low wage part-time jobs).

The problem with this “miracle” is that inflation leads to price explosions, which we have already experienced. The average American is spending around 30% more for goods, services and housing compared to what they were spending in 2020. This is what happens when you have too much money chasing too few goods and limited production.

The jobs market looks great on paper, but the majority of jobs generated in the past few years are jobs that returned after the covid lockdowns ended. The rest are jobs created through monetary stimulus and the artificial retail rush. Part time low wage service sector jobs are not going to keep the country rolling for very long in a stagflation environment. The question is, what happens now that the stimulus punch bowl has been removed?

Just as we witnessed in the 1920s, Americans have turned to debt to make up for higher prices and stagnant wages by maxing out their credit cards. With the central bank keeping interest rates high, the credit safety net will soon falter. This condition also goes for businesses; the same businesses that will jump headlong into mass layoffs when they realize the party is over. It happened during the Great Depression and it will happen again today.

Cracks in the foundation

We saw cracks in the narrative of the financial structure in 2023 with the banking crisis, and without the Federal Reserve backstop policy many more small and medium banks would have dropped dead. The weakness of U.S. banks is offset by the relative strength of the U.S. dollar, which lures in foreign investors hoping to protect their wealth using dollar denominated assets.

But something is amiss. Gold and bitcoin have rocketed higher along with economically sensitive assets and the dollar. This is the opposite of what’s supposed to happen. Gold and BTC are supposed to be hedges against a weak dollar and a weak economy, right? If global faith in the dollar and in the U.S. economy is so high, why are investors diving into protective assets like gold?

Again, as noted above, inflation distorts everything.

Tens of trillions of extra dollars printed by the Fed are floating around and it’s no surprise that much of that cash is flooding into the economy which simply pushes higher right along with prices on the shelf. But, gold and bitcoin are telling us a more honest story about what’s really happening.

Right now, the U.S. government is adding around $600 billion per month to the national debt as the Fed holds rates higher to fight inflation. This debt is going to crush America’s financial standing for global investors who will eventually ask HOW the U.S. is going to handle that growing millstone? As I predicted years ago, the Fed has created a perfect Catch-22 scenario in which the U.S. must either return to rampant inflation, or, face a debt crisis. In either case, U.S. dollar-denominated assets will lose their appeal and their prices will plummet.

“Healthy” GDP is a complete farce

GDP is the most common out-of-context stat used by governments to convince the citizenry that all is well. It is yet another stat that is entirely manipulated by inflation. It is also manipulated by the way in which modern governments define “economic activity.”

GDP is primarily driven by spending. Meaning, the higher inflation goes, the higher prices go, and the higher GDP climbs (to a point). Eventually prices go too high, credit cards tap out and spending ceases. But, for a short time inflation makes GDP (as well as retail sales) look good.

Another factor that creates a bubble is the fact that government spending is actually included in the calculation of GDP. That’s right, every dollar of your tax money that the government wastes helps the establishment by propping up GDP numbers. This is why government spending increases will never stop – It’s too valuable for them to spend as a way to make the economy appear healthier than it is.

The REAL economy is eclipsing the fake economy

The bottom line is that Americans used to be able to ignore the warning signs because their bank accounts were not being directly affected. This is over. Now, every person in the country is dealing with a massive decline in buying power and higher prices across the board on everything – from food and fuel to housing and financial assets alike. Even the wealthy are seeing a compression to their profit and many are struggling to keep their businesses in the black.

The unfortunate truth is that the elections of 2024 will probably be the turning point at which the whole edifice comes tumbling down. Even if the public votes for change, the system is already broken and cannot be repaired without a complete overhaul.

We have consistently avoided taking our medicine and our disease has gotten worse and worse.

People have lost faith in the economy because they have not faced this kind of uncertainty since the 1930s. Even the stagflation crisis of the 1970s will likely pale in comparison to what is about to happen. On the bright side, at least a large number of Americans are aware of the threat, as opposed to the 1920s when the vast majority of people were utterly conned by the government, the banks and the media into thinking all was well. Knowing is the first step to preparing.

The second step is securing your own financial future – that’s where physical precious metals can play a role. Diversifying your savings with inflation-resistant, uninflatable assets whose intrinsic value doesn’t rely on a counterparty’s promise to pay adds resilience to your savings. That’s the main reason physical gold and silver have been the safe haven store-of-value assets of choice for centuries (among both the elite and the everyday citizen).

* * *

As the world moves away from dollars and toward Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), is your 401(k) or IRA really safe? A smart and conservative move is to diversify into a physical gold IRA. That way your savings will be in something solid and enduring. Get your FREE info kit on Gold IRAs from Birch Gold Group. No strings attached, just peace of mind. Click here to secure your future today.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International13 hours ago

International13 hours agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges