The most common tick found on humans in Georgia is the lone star tick — an aggressive seeker of blood that can spread dangerous pathogens through its bites.

Emory University researchers combined field data with spatial-analysis techniques to map the distribution of the lone star tick across the state. The journal Parasites & Vectors published the research, which identifies specific environmental conditions associated with this tick species, Amblyomma americanum, in Georgia.

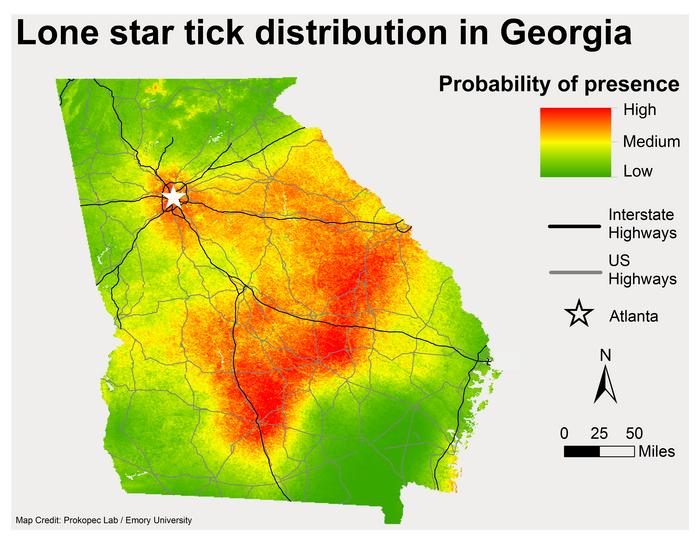

The areas with the highest probability for the presence of lone star ticks include parts of the Southeastern Plains and Piedmont ecoregions of the state, including metro Atlanta.

“We found that these regions contain sweet spots for the lone star tick,” says Stephanie Bellman, first author of the study and an MD/PhD student in Emory’s School of Medicine and Rollins School of Public Health. “They tend to be more prevalent in forested areas of mid-elevation — not too high or too low — and in soils that retain moisture but are not swampy.”

The study maps the distribution at the scale of one square kilometer. That resolution is far finer than the currently available information, which is limited to the county level and does not encompass the state.

“As the weather warms and people start getting into the outdoors more, we hope our data can be used to target areas for tick-bite prevention messaging,” says Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, professor in Emory’s Department of Environmental Sciences and senior author of the study.

Vazquez-Prokopec is a leading expert in vector-borne diseases — infections transmitted among humans and animals by the bite of a living organism, such as a tick or a mosquito.

Diseases the lone star tick is known to transmit include ehrlichiosis, southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) and Heartland virus disease — which was first identified in the United States in 2009. The bite of the lone star tick is also associated with a potentially life-threatening allergy to red meat and dairy products known as alpha-gal syndrome.

Mapping the lone star tick is another step in a comprehensive Emory project to track and monitor the array of tick species in Georgia and the diseases that they can spread — including those caused by emerging pathogens.

Tickborne diseases are on the rise, far surpassing the incidence of diseases spread by mosquitos in the United States. While Lyme disease is the most common, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recognizes 18 tickborne diseases in the country.

“We need to educate people that the environment that they grew up in is likely very different in terms of the number and types of ticks and the pathogens that they are carrying,” Vazquez-Prokopec says.

Climate change is fueling warmer and shorter winters, increasing opportunities for some species of ticks to breed more frequently and expand their ranges. Land-use changes are also strongly associated with tickborne diseases, as more human habitats encroach on wooded areas and the loss of natural habitat forces wildlife to live in denser populations.

“Georgia is a tick haven in general,” Bellman says, “since we have a long warm season and such a diversity of habitats.”

The researchers decided to focus first on mapping the distribution of the lone star tick because it is the dominant tick species in Georgia and can spread an array of pathogens. In 2019, the Emory researchers found that Heartland virus is circulating in lone star ticks in Georgia, an emerging pathogen that is not well understood.

Named for a bright, yellowish-white spot on its back, the lone star tick is widely distributed in wooded areas across the Southeast, Eastern and Midwest United States. It is tiny —in the nymph stage it is about the size of a sesame seed and as an adult it is barely a quarter-of-an-inch in diameter as an adult.

Despite its tiny size, the lone star tick is aggressive in its quest for blood meals. “They can sense carbon dioxide from your exhaled breath and the vibrations from your movement in a forest,” Bellman says. “They climb up onto vegetation and reach out their legs to grab onto you as you pass by.”

For the current study, Bellman led crews of Emory students, known as “the tick team,” in field surveys. They used “flagging” as a tick-collection technique. A white flannel cloth attached to a pole is swished in a figure-eight motion through the underbrush. Tweezers are used to transfer any ticks found on the flannel into a vial.

Tick team members surveyed 198 locations at 43 state parks and wildlife management areas across the state, from March to July 2022. Analyses combined the site-sampling data with environmental variables — including type of vegetation, land use, climate, elevation and other factors — characteristic for six different ecoregions of Georgia.

Lone star ticks were found in all of the ecoregions except for the mountainous Blue Ridge ecoregion in the northeast corner of the state. The majority of the ticks were found in forested areas of the Piedmont, Southeastern Plains and Southern Coastal Plains ecoregions.

The researchers encourage people to follow the recommendations of the CDC for preventing tick bites. And while the map for the lone star tick provides guidance on the likelihood of encountering the most prevalent human-biting tick in the state, there are other tick species that the researchers have yet to map.

The black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis), which can transmit the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, for instance, is also established in Georgia. Lyme disease, however, is relatively uncommon in in the state for reasons that are not yet well-understood.

The researchers are also investigating the Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) in Georgia. Long established in China, Japan, Russia and parts of the Pacific, the Asian longhorned tick was first detected in the United States in 2017, in New Jersey, and has since spread to 19 states. It was found on farm animals in Pickens County, Georgia in 2021.

The Asian longhorned tick reproduces asexually and a single female can generate as many as 100,000 eggs, rapidly producing massive amounts of offspring that feed on livestock. So many ticks can be covering a single sheep or cow that the loss of blood physically weakens or, in extreme cases, kills the animal.

While it is often associated with livestock, the Emory research team recently found Asian longhorned ticks in the Buck Shoals Wildlife Management Area in White County, Georgia.

The Asian longhorned tick carries bacterial and viral pathogens that can infect humans, including severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), also known as Dabie bandavirus. Human cases of SFTS, a hemorrhagic fever, emerged in China in 2009 and have since been identified in other parts of Asia, although not in the United States.

Also of concern is the fact that the Heartland virus shares genomic similarities with SFTS, which suggests the Asian longhorn tick could potentially transmit this emerging pathogen.

The Emory team has been finding the Heartland virus in lone star ticks collected from central Georgia starting in 2019. They have continued to find Heartland virus in at least some of the ticks collected from that area nearly annually through 2023. (They did not perform collections in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.)

More than 60 cases of Heartland virus disease have been reported in the United States, according to the latest CDC statistics. Many of the identified cases were severe enough to require hospitalization, and a few individuals with co-morbidities have died.

The actual number of people who may have been infected with Heartland virus is believed to be higher, however, since the virus is not well known and tests are rarely ordered for it. Complicating the issue is the fact that symptoms of Heartland virus are akin to those of many tickborne illnesses: fever, fatigue, headache, nausea, diarrhea and muscle or joint pain.

“Human cases of Heartland virus are rare now, but we don’t know whether that could change,” Bellman says. “We need to gather more baseline data and learn how it spreads in the environment so that we have the evidence we need to potentially prevent, or limit, its spread.”

Anne Piantadosi, assistant professor in Emory School of Medicine’s Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, is co-author of the study.

Co-authors also include five Emory students who conducted fieldwork: Ellie Fausett (who has since graduated with a joint environmental sciences/MPH degree); Leah Aeschleman and Audrey Long (who have since received master’s of public health degrees from Rollins School of Public Health); Josie Pilchik, (who graduated with a bachelor’s in biology) and Isabella Roeske (an Emory senior majoring in environmental sciences).

Work on the current paper was funded by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institutes of Health, Emory University and the Emory MP3 Initiative and Infectious Disease Across Scales Training Program.

Journal

Parasites & Vectors

DOI

10.1186/s13071-024-06142-7

Method of Research

Data/statistical analysis

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

sMapping the distribution of Amblyomma americanum in Georgia, USA

Article Publication Date

11-Feb-2024