Government

15 US Agencies Knew Wuhan Lab Was “Trying To Create A Coronavirus Like COVID-19”: Rand Paul

15 US Agencies Knew Wuhan Lab Was "Trying To Create A Coronavirus Like COVID-19": Rand Paul

While a massive body of evidence exists on the…

While a massive body of evidence exists on the origins of COVID-19, Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) is conducting his own investigation into the matter.

In a Tuesday op-ed, Paul writes that government officials from 15 federal agencies "knew in 2018 that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was trying to create a coronavirus like COVID-19."

These officials knew that the Chinese lab was proposing to create a COVID 19-like virus and not one of these officials revealed this scheme to the public. In fact, 15 agencies with knowledge of this project have continuously refused to release any information concerning this alarming and dangerous research.

Government officials representing at least 15 federal agencies were briefed on a project proposed by Peter Daszak’s EcoHealth Alliance and the Wuhan Institute of Virology. -Rand Paul

Paul is talking about the DEFUSE project, which was revealed after DRASTIC Research uncovered documents showing that DARPA had been presented with a proposal for EcoHealth to perform gain-of-function research on bat coronavirus.

New documents released by Drastic Research show Peter Daszak and the EcoHealth Alliance had applied for funds that would allow them to further modify coronavirus spike proteins and find potential furin cleavage sites.

— Rep. Gallagher Press Office (@RepGallagher) September 23, 2021

Rep. Gallagher explains why that's so important. pic.twitter.com/6aEPyuW7Go

And according to Rand Paul, officials from 15 agencies knew about this. While the project was never funded (DARPA called it too dangerous) - Paul writes: "This project, the DEFUSE project, proposed to insert a furin cleavage site into a coronavirus to create a novel chimeric virus that would have been shockingly similar to the COVID-19 virus."

And what does this mean?

It means that at least 15 federal agencies knew from the beginning of the pandemic that EcoHealth Alliance and the Wuhan Institute of Virology were seeking federal funding in 2018 to create a virus genetically very similar if not identical to COVID-19.

Disturbingly, not one of these 15 agencies spoke up to warn us that the Wuhan Institute of Virology had been pitching this research. Not one of these agencies warned anyone that this Chinese lab had already put together plans to create such a virus.

Peter Daszak concealed this proposal. University of North Carolina scientist Ralph Baric, a named collaborator on the DEFUSE project, failed to reveal that the Wuhan Institute of Virology had already proposed to create a virus similar to COVID-19.

And now we know that 15 agencies heard the proposal and when each agency discovered that COVID-19 was strangely similar to DEFUSE’s proposed virus creation, not one agency head stepped forward to warn the public that the virus might be man-made and therefore already adapted to transmit freely among humans. -Rand Paul

Paul further writes that Fauci's NIAID was not only briefed on the DEFUSE proposal, his "Rocky Mountain Lab" was named as a partner in it along with the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Newly obtained documents confirm yet again Fauci lied about COVID. Fauci’s NIH lab was a partner with Wuhan on a proposal to engineer a highly transmissible coronavirus in 2018. But he wasn’t alone, 15 government agencies knew about it and said nothing. Americans deserve answers.…

— Rand Paul (@RandPaul) April 9, 2024

Meanwhile, researcher Ian Lipkin, one of the authors of the "proximal origins" coverup paper, was also part of the DEFUSE plan - which he never revealed publicly.

"Did NIAID warn us? Did Anthony Fauci warn us? No! All lips remained sealed," writes Paul.

International

Pfizer And A Corruption Too Deep To Fix

Pfizer And A Corruption Too Deep To Fix

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

Old movies and new ones often turn on the theme of…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

Old movies and new ones often turn on the theme of corruption. For generations, viewers have enjoyed discovering the ins and outs of a gang of people who are up to no good, financially and otherwise.

It’s always a shock to see the way the insiders treat each other so brutally, and how they lie, cheat, and steal to get their way. It’s especially satisfying when they get caught in the end.

Countless movies in the old days followed this basic plot.

One of my favorites is the American classic “On the Waterfront” (1954) with Marlon Brando, Eva Marie Saint, and Karl Malden. It’s the story of a rough gang of thugs that has taken control of a longshoreman’s union. They pillage the workers for dues and make paychecks contingent on loyalty.

For years, everyone in the union is told to be “D&D” or deaf and dumb, never saying a word to the authorities for fear of bad outcomes. As the corruption gets worse, the tactics of enforcement grow more violent. New Jersey kicks off a crime commission to look into the problem with the focus on a murder. A local priest plays a role in convincing a worker who is tight with the gang to rat on the bad guys.

It all turns out well in the end, even if Brando gets badly beaten up. The bad guys are overturned and the workers get their union back. The movie is a brilliant reflection of a culture at the time: yes, there are imperfections but we are making great progress to root out the bad and replace it with the good, thanks to moral leadership and courage.

But notice how the plot absolutely depends on the existence of a not-corrupt higher power.

That’s almost always the case in the old movies. Once the authorities find out that something bad is happening, they work to clean it up. Their success turns on the ethical tenacity of one insider who is willing to stand up for what is right. To make that courage operational, you need means of redress that are not part of the problem.

That’s all great but we have a different problem in our own time. The higher powers on which we depend for redress are themselves part of the issue.

This truly came home to me lately with the Supreme Court hearing for Murthy v. Missouri, which documented how dozens of federal agencies worked with social media companies, directly and indirectly, to censor free speech.

Seems like a no-brainer of a case. But based on the oral arguments, a third of the court couldn’t see the problem at all. A third was confused. The last third got that this was a problem for the First Amendment.

This is alarming but a realistic accounting of where we are in the United States today: divided by thirds into clear, confused, and corrupt.

In other words, we can no longer count on the highest powers and the most authoritative institutions to save us from evil.

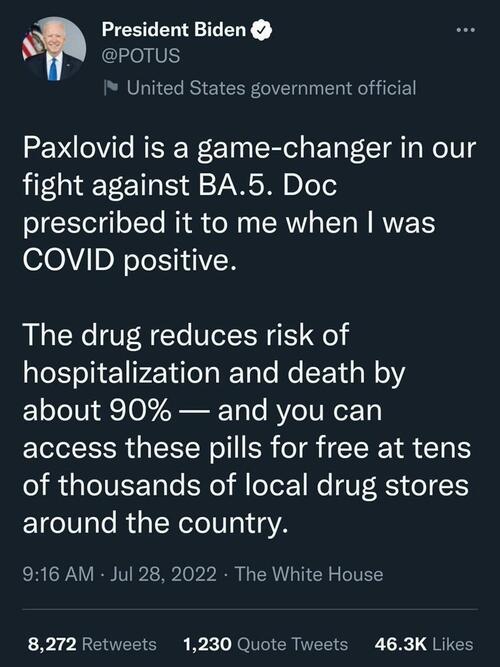

Let’s cite an astonishing example from this past week that should have been headline news but was utterly invisible to legacy media (speaking of corruption at the very top). The case involves the COVID medication Paxlovid. It was approved under “emergency use” in December 2021, and trumpeted by Fauci, President Biden, and the rest of the usual crowd. It was 90 percent effective, they said!

The White House authorized $11 billion and more to pay for it, and dispatched the whole army of media mavens to push this thing. The White House was able to claim it was free, if you had insurance but even that would last only for so long. Eventually, the consumer had to pay and it was nearly $1,500 for 20 pills.

In many places, the entire medical profession was insisting that this was the way to treat COVID, even as Ivermectin and Hydroxychloroquine were banned or impossible to get.

Paxlovid was greeted with all the usual hosannas from the drug company as echoed by big media. The drug is 89 percent effective, they kept saying. The governments of Canada, the United States, and the UK all celebrated and showered Pfizer with multiple rounds of billions of dollars.

But even from the outset, it seems there were many reports of rebounds. The drug would reduce symptoms for a few days even to the point of generating a negative test but then COVID would come back. This happened often enough that pharma skeptics grew deeply suspicious of it, especially because of such a very long run of patented failings in this realm.

Mr. Biden, for example, seems to have gotten COVID four times after being treated repeatedly with Paxlovid. So too with Biden’s wife. The same happened with Fauci himself. Most every prominent person reported something similar. But that did not stop the gravy train from running, with the entire medical professional rallying around this drug.

COVID-19 treatment pill Paxlovid in a box at Misericordia hospital in Grosseto, Italy, on Feb. 8, 2022. (Jennifer Lorenzini/Reuters)

From the outset, The Epoch Times was reporting skeptically about it, the only media venue to do so. More and more doubts emerged, not in official circles but online in alternative media.

Now we come to the kicker. Pfizer itself has finally published its randomized placebo-controlled trial of several hundred individuals with the Delta variant, which would have been two and a half years ago. The title of the results as published in the New England Journal of Medicine: “Nirmatrelvir for Vaccinated or Unvaccinated Adult Outpatients with Covid-19.”

Notice the absence of the word Paxlovid, making it all the more difficult for regular people to find. Nirmatrelvir is the clinical name.

And the conclusion: “Nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was not associated with a significantly shorter time to sustained alleviation of Covid-19 symptoms than placebo, and the usefulness of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir in patients who are not at high risk for severe Covid-19 has not been established.”

In other words: this drug does not work. At all. It is no better than nothing. It is not useful. Countless billions later and this is what we have, a completely useless thing. At best. In fact, that Pfizer itself admits that its own drug is useless, one wonders what the bad news is!

The drug was not a game changer at all. It was a vast waste of money.

This whole thing stuns me, even now, even after everything we know about the industry, its relationship to government, the way the media goes along with all the nonsense, the manner in which all top officials go along with the racket. This to me is as much a scandal as the vaccine in some ways.

You will notice that you have not seen this reported in any mainstream media, even though it appears in the top medicine journal in the United States. That’s because the mainstream media is entirely in the pay of pharma.

The conspiracy is out in the open, and all official channels are implicated. There seems to be zero accountability or appeal. It’s no wonder that RFK, Jr., is calling for racketeering investigations to be made against the whole industry and its industrial partners. This is aggressive robbery and fraud.

Very few people even know to care because they are not being told the brutal facts of the case.

One also wonders how it is that Pfizer held onto this study for two years before releasing it.

Why would Pfizer choose just now to announce that its wonder drug is actually useless? My own theory: its accounting ledgers are showing that the drug’s period of high profitability is at an end. There’s no more high-margin profits associated with it. Might as well retire it.

With a complicit legacy media, it has no egg on its face. It can just chalk up its wild Paxlovid push as profitable and done, like a seasonal beer or a pumpkin-spice latte. There is essentially no downside to moving onward to other products in its arsenal.

But think about what this means for this company and for the system that protects it. What does this say about the vaccine? What does it mean for the whole network of protection, from regulators to journals to media? They are all in on the game. And how deep and wide is this game?

What we have in operation here is a form of vampiric capitalism, an entire industry that has colonized our health and bodies in the interest of wealth extraction even though its products do not work and actually make us more sick, providing more opportunities to innovate products that do more of the same.

It’s time that this system came to an end, but where is the crime commission to investigate and stop it?

It doesn’t exist. That’s the great dilemma of our time.

Government

“An Open-Minded Spirit No Longer Exists Within NPR” – NPR Veteran Excoriates Outlet Over Hunter, Russiagate Activism

"An Open-Minded Spirit No Longer Exists Within NPR" – NPR Veteran Excoriates Outlet Over Hunter, Russiagate Activism

Authored by Uri Berliner…

Authored by Uri Berliner via The Free Press (emphasis ours),

You know the stereotype of the NPR listener: an EV-driving, Wordle-playing, tote bag–carrying coastal elite. It doesn’t precisely describe me, but it’s not far off. I’m Sarah Lawrence–educated, was raised by a lesbian peace activist mother, I drive a Subaru, and Spotify says my listening habits are most similar to people in Berkeley.

I fit the NPR mold. I’ll cop to that.

So when I got a job here 25 years ago, I never looked back. As a senior editor on the business desk where news is always breaking, we’ve covered upheavals in the workplace, supermarket prices, social media, and AI.

It’s true NPR has always had a liberal bent, but during most of my tenure here, an open-minded, curious culture prevailed. We were nerdy, but not knee-jerk, activist, or scolding.

In recent years, however, that has changed. Today, those who listen to NPR or read its coverage online find something different: the distilled worldview of a very small segment of the U.S. population.

If you are conservative, you will read this and say, duh, it’s always been this way.

But it hasn’t.

For decades, since its founding in 1970, a wide swath of America tuned in to NPR for reliable journalism and gorgeous audio pieces with birds singing in the Amazon. Millions came to us for conversations that exposed us to voices around the country and the world radically different from our own—engaging precisely because they were unguarded and unpredictable. No image generated more pride within NPR than the farmer listening to Morning Edition from his or her tractor at sunrise.

Back in 2011, although NPR’s audience tilted a bit to the left, it still bore a resemblance to America at large. Twenty-six percent of listeners described themselves as conservative, 23 percent as middle of the road, and 37 percent as liberal.

By 2023, the picture was completely different: only 11 percent described themselves as very or somewhat conservative, 21 percent as middle of the road, and 67 percent of listeners said they were very or somewhat liberal. We weren’t just losing conservatives; we were also losing moderates and traditional liberals.

An open-minded spirit no longer exists within NPR, and now, predictably, we don’t have an audience that reflects America.

That wouldn’t be a problem for an openly polemical news outlet serving a niche audience. But for NPR, which purports to consider all things, it’s devastating both for its journalism and its business model.

* * *

Like many unfortunate things, the rise of advocacy took off with Donald Trump. As in many newsrooms, his election in 2016 was greeted at NPR with a mixture of disbelief, anger, and despair. (Just to note, I eagerly voted against Trump twice but felt we were obliged to cover him fairly.) But what began as tough, straightforward coverage of a belligerent, truth-impaired president veered toward efforts to damage or topple Trump’s presidency.

Persistent rumors that the Trump campaign colluded with Russia over the election became the catnip that drove reporting. At NPR, we hitched our wagon to Trump’s most visible antagonist, Representative Adam Schiff.

Schiff, who was the top Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, became NPR’s guiding hand, its ever-present muse. By my count, NPR hosts interviewed Schiff 25 times about Trump and Russia. During many of those conversations, Schiff alluded to purported evidence of collusion. The Schiff talking points became the drumbeat of NPR news reports.

But when the Mueller report found no credible evidence of collusion, NPR’s coverage was notably sparse. Russiagate quietly faded from our programming.

It is one thing to swing and miss on a major story. Unfortunately, it happens. You follow the wrong leads, you get misled by sources you trusted, you’re emotionally invested in a narrative, and bits of circumstantial evidence never add up. It’s bad to blow a big story.

What’s worse is to pretend it never happened, to move on with no mea culpas, no self-reflection. Especially when you expect high standards of transparency from public figures and institutions, but don’t practice those standards yourself. That’s what shatters trust and engenders cynicism about the media.

Russiagate was not NPR’s only miscue.

In October 2020, the New York Post published the explosive report about the laptop Hunter Biden abandoned at a Delaware computer shop containing emails about his sordid business dealings. With the election only weeks away, NPR turned a blind eye. Here’s how NPR’s managing editor for news at the time explained the thinking: “We don’t want to waste our time on stories that are not really stories, and we don’t want to waste the listeners’ and readers’ time on stories that are just pure distractions.”

But it wasn’t a pure distraction, or a product of Russian disinformation, as dozens of former and current intelligence officials suggested. The laptop did belong to Hunter Biden. Its contents revealed his connection to the corrupt world of multimillion-dollar influence peddling and its possible implications for his father.

The laptop was newsworthy. But the timeless journalistic instinct of following a hot story lead was being squelched. During a meeting with colleagues, I listened as one of NPR’s best and most fair-minded journalists said it was good we weren’t following the laptop story because it could help Trump.

When the essential facts of the Post’s reporting were confirmed and the emails verified independently about a year and a half later, we could have fessed up to our misjudgment. But, like Russia collusion, we didn’t make the hard choice of transparency.

Politics also intruded into NPR’s Covid coverage, most notably in reporting on the origin of the pandemic. One of the most dismal aspects of Covid journalism is how quickly it defaulted to ideological story lines. For example, there was Team Natural Origin—supporting the hypothesis that the virus came from a wild animal market in Wuhan, China. And on the other side, Team Lab Leak, leaning into the idea that the virus escaped from a Wuhan lab.

The lab leak theory came in for rough treatment almost immediately, dismissed as racist or a right-wing conspiracy theory. Anthony Fauci and former NIH head Francis Collins, representing the public health establishment, were its most notable critics. And that was enough for NPR. We became fervent members of Team Natural Origin, even declaring that the lab leak had been debunked by scientists.

But that wasn’t the case.

When word first broke of a mysterious virus in Wuhan, a number of leading virologists immediately suspected it could have leaked from a lab there conducting experiments on bat coronaviruses. This was in January 2020, during calmer moments before a global pandemic had been declared, and before fear spread and politics intruded.

Reporting on a possible lab leak soon became radioactive. Fauci and Collins apparently encouraged the March publication of an influential scientific paper known as “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2.” Its authors wrote they didn’t believe “any type of laboratory-based scenario is plausible.”

But the lab leak hypothesis wouldn’t die. And understandably so. In private, even some of the scientists who penned the article dismissing it sounded a different tune. One of the authors, Andrew Rambaut, an evolutionary biologist from Edinburgh University, wrote to his colleagues, “I literally swivel day by day thinking it is a lab escape or natural.”

Over the course of the pandemic, a number of investigative journalists made compelling, if not conclusive, cases for the lab leak. But at NPR, we weren’t about to swivel or even tiptoe away from the insistence with which we backed the natural origin story. We didn’t budge when the Energy Department—the federal agency with the most expertise about laboratories and biological research—concluded, albeit with low confidence, that a lab leak was the most likely explanation for the emergence of the virus.

Instead, we introduced our coverage of that development on February 28, 2023, by asserting confidently that “the scientific evidence overwhelmingly points to a natural origin for the virus.”

When a colleague on our science desk was asked why they were so dismissive of the lab leak theory, the response was odd. The colleague compared it to the Bush administration’s unfounded argument that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, apparently meaning we won’t get fooled again. But these two events were not even remotely related. Again, politics were blotting out the curiosity and independence that ought to have been driving our work.

I’m offering three examples of widely followed stories where I believe we faltered. Our coverage is out there in the public domain. Anyone can read or listen for themselves and make their own judgment. But to truly understand how independent journalism suffered at NPR, you need to step inside the organization.

You need to start with former CEO John Lansing. Lansing came to NPR in 2019 from the federally funded agency that oversees Voice of America. Like others who have served in the top job at NPR, he was hired primarily to raise money and to ensure good working relations with hundreds of member stations that acquire NPR’s programming.

After working mostly behind the scenes, Lansing became a more visible and forceful figure after the killing of George Floyd in May 2020. It was an anguished time in the newsroom, personally and professionally so for NPR staffers. Floyd’s murder, captured on video, changed both the conversation and the daily operations at NPR.

Given the circumstances of Floyd’s death, it would have been an ideal moment to tackle a difficult question: Is America, as progressive activists claim, beset by systemic racism in the 2020s—in law enforcement, education, housing, and elsewhere? We happen to have a very powerful tool for answering such questions: journalism. Journalism that lets evidence lead the way.

But the message from the top was very different. America’s infestation with systemic racism was declared loud and clear: it was a given. Our mission was to change it.

“When it comes to identifying and ending systemic racism,” Lansing wrote in a companywide article, “we can be agents of change. Listening and deep reflection are necessary but not enough. They must be followed by constructive and meaningful steps forward. I will hold myself accountable for this.”

And we were told that NPR itself was part of the problem. In confessional language he said the leaders of public media, “starting with me—must be aware of how we ourselves have benefited from white privilege in our careers. We must understand the unconscious bias we bring to our work and interactions. And we must commit ourselves—body and soul—to profound changes in ourselves and our institutions.”

He declared that diversity—on our staff and in our audience—was the overriding mission, the “North Star” of the organization. Phrases like “that’s part of the North Star” became part of meetings and more casual conversation.

Race and identity became paramount in nearly every aspect of the workplace. Journalists were required to ask everyone we interviewed their race, gender, and ethnicity (among other questions), and had to enter it in a centralized tracking system. We were given unconscious bias training sessions. A growing DEI staff offered regular meetings imploring us to “start talking about race.” Monthly dialogues were offered for “women of color” and “men of color.” Nonbinary people of color were included, too.

These initiatives, bolstered by a $1 million grant from the NPR Foundation, came from management, from the top down. Crucially, they were in sync culturally with what was happening at the grassroots—among producers, reporters, and other staffers. Most visible was a burgeoning number of employee resource (or affinity) groups based on identity.

They included MGIPOC (Marginalized Genders and Intersex People of Color mentorship program); Mi Gente (Latinx employees at NPR); NPR Noir (black employees at NPR); Southwest Asians and North Africans at NPR; Ummah (for Muslim-identifying employees); Women, Gender-Expansive, and Transgender People in Technology Throughout Public Media; Khevre (Jewish heritage and culture at NPR); and NPR Pride (LGBTQIA employees at NPR).

All this reflected a broader movement in the culture of people clustering together based on ideology or a characteristic of birth. If, as NPR’s internal website suggested, the groups were simply a “great way to meet like-minded colleagues” and “help new employees feel included,” it would have been one thing.

But the role and standing of affinity groups, including those outside NPR, were more than that. They became a priority for NPR’s union, SAG-AFTRA—an item in collective bargaining. The current contract, in a section on DEI, requires NPR management to “keep up to date with current language and style guidance from journalism affinity groups” and to inform employees if language differs from the diktats of those groups. In such a case, the dispute could go before the DEI Accountability Committee.

In essence, this means the NPR union, of which I am a dues-paying member, has ensured that advocacy groups are given a seat at the table in determining the terms and vocabulary of our news coverage.

Conflicts between workers and bosses, between labor and management, are common in workplaces. NPR has had its share. But what’s notable is the extent to which people at every level of NPR have comfortably coalesced around the progressive worldview.

And this, I believe, is the most damaging development at NPR: the absence of viewpoint diversity.

* * *

There’s an unspoken consensus about the stories we should pursue and how they should be framed. It’s frictionless—one story after another about instances of supposed racism, transphobia, signs of the climate apocalypse, Israel doing something bad, and the dire threat of Republican policies. It’s almost like an assembly line.

The mindset prevails in choices about language. In a document called NPR Transgender Coverage Guidance—disseminated by news management—we’re asked to avoid the term biological sex. (The editorial guidance was prepared with the help of a former staffer of the National Center for Transgender Equality.) The mindset animates bizarre stories—on how The Beatles and bird names are racially problematic, and others that are alarmingly divisive; justifying looting, with claims that fears about crime are racist; and suggesting that Asian Americans who oppose affirmative action have been manipulated by white conservatives.

More recently, we have approached the Israel-Hamas war and its spillover onto streets and campuses through the “intersectional” lens that has jumped from the faculty lounge to newsrooms. Oppressor versus oppressed. That’s meant highlighting the suffering of Palestinians at almost every turn while downplaying the atrocities of October 7, overlooking how Hamas intentionally puts Palestinian civilians in peril, and giving little weight to the explosion of antisemitic hate around the world.

For nearly all my career, working at NPR has been a source of great pride. It’s a privilege to work in the newsroom at a crown jewel of American journalism. My colleagues are congenial and hardworking.

I can’t count the number of times I would meet someone, describe what I do, and they’d say, “I love NPR!”

And they wouldn’t stop there. They would mention their favorite host or one of those “driveway moments” where a story was so good you’d stay in your car until it finished.

It still happens, but often now the trajectory of the conversation is different. After the initial “I love NPR,” there’s a pause and a person will acknowledge, “I don’t listen as much as I used to.” Or, with some chagrin: “What’s happening there? Why is NPR telling me what to think?”

In recent years I’ve struggled to answer that question. Concerned by the lack of viewpoint diversity, I looked at voter registration for our newsroom. In D.C., where NPR is headquartered and many of us live, I found 87 registered Democrats working in editorial positions and zero Republicans. None.

So on May 3, 2021, I presented the findings at an all-hands editorial staff meeting. When I suggested we had a diversity problem with a score of 87 Democrats and zero Republicans, the response wasn’t hostile. It was worse. It was met with profound indifference. I got a few messages from surprised, curious colleagues. But the messages were of the “oh wow, that’s weird” variety, as if the lopsided tally was a random anomaly rather than a critical failure of our diversity North Star.

In a follow-up email exchange, a top NPR news executive told me that she had been “skewered” for bringing up diversity of thought when she arrived at NPR. So, she said, “I want to be careful how we discuss this publicly.”

For years, I have been persistent. When I believe our coverage has gone off the rails, I have written regular emails to top news leaders, sometimes even having one-on-one sessions with them. On March 10, 2022, I wrote to a top news executive about the numerous times we described the controversial education bill in Florida as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill when it didn’t even use the word gay. I pushed to set the record straight, and wrote another time to ask why we keep using that word that many Hispanics hate—Latinx. On March 31, 2022, I was invited to a managers’ meeting to present my observations.

Throughout these exchanges, no one has ever trashed me. That’s not the NPR way. People are polite. But nothing changes. So I’ve become a visible wrong-thinker at a place I love. It’s uncomfortable, sometimes heartbreaking.

Even so, out of frustration, on November 6, 2022, I wrote to the captain of ship North Star—CEO John Lansing—about the lack of viewpoint diversity and asked if we could have a conversation about it. I got no response, so I followed up four days later. He said he would appreciate hearing my perspective and copied his assistant to set up a meeting. On December 15, the morning of the meeting, Lansing’s assistant wrote back to cancel our conversation because he was under the weather. She said he was looking forward to chatting and a new meeting invitation would be sent. But it never came.

I won’t speculate about why our meeting never happened. Being CEO of NPR is a demanding job with lots of constituents and headaches to deal with. But what’s indisputable is that no one in a C-suite or upper management position has chosen to deal with the lack of viewpoint diversity at NPR and how that affects our journalism.

Which is a shame. Because for all the emphasis on our North Star, NPR’s news audience in recent years has become less diverse, not more so. Back in 2011, our audience leaned a bit to the left but roughly reflected America politically; now, the audience is cramped into a smaller, progressive silo.

Despite all the resources we’d devoted to building up our news audience among blacks and Hispanics, the numbers have barely budged. In 2023, according to our demographic research, 6 percent of our news audience was black, far short of the overall U.S. adult population, which is 14.4 percent black. And Hispanics were only 7 percent, compared to the overall Hispanic adult population, around 19 percent. Our news audience doesn’t come close to reflecting America. It’s overwhelmingly white and progressive, and clustered around coastal cities and college towns.

These are perilous times for news organizations. Last year, NPR laid off or bought out 10 percent of its staff and canceled four podcasts following a slump in advertising revenue. Our radio audience is dwindling and our podcast downloads are down from 2020. The digital stories on our website rarely have national impact. They aren’t conversation starters. Our competitive advantage in audio—where for years NPR had no peer—is vanishing. There are plenty of informative and entertaining podcasts to choose from.

Even within our diminished audience, there’s evidence of trouble at the most basic level: trust.

In February, our audience insights team sent an email proudly announcing that we had a higher trustworthy score than CNN or The New York Times. But the research from Harris Poll is hardly reassuring. It found that “3-in-10 audience members familiar with NPR said they associate NPR with the characteristic ‘trustworthy.’ ” Only in a world where media credibility has completely imploded would a 3-in-10 trustworthy score be something to boast about.

With declining ratings, sorry levels of trust, and an audience that has become less diverse over time, the trajectory for NPR is not promising. Two paths seem clear. We can keep doing what we’re doing, hoping it will all work out. Or we could start over, with the basic building blocks of journalism. We could face up to where we’ve gone wrong. News organizations don’t go in for that kind of reckoning. But there’s a good reason for NPR to be the first: we’re the ones with the word public in our name.

Despite our missteps at NPR, defunding isn’t the answer. As the country becomes more fractured, there’s still a need for a public institution where stories are told and viewpoints exchanged in good faith. Defunding, as a rebuke from Congress, wouldn’t change the journalism at NPR. That needs to come from within.

A few weeks ago, NPR welcomed a new CEO, Katherine Maher, who’s been a leader in tech. She doesn’t have a news background, which could be an asset given where things stand. I’ll be rooting for her. It’s a tough job. Her first rule could be simple enough: don’t tell people how to think. It could even be the new North Star.

Uri Berliner is a senior business editor and reporter at NPR. His work has been recognized with a Peabody Award, a Loeb Award, an Edward R. Murrow Award, and a Society of Professional Journalists New America Award, among others. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @uberliner.

And fast https://t.co/JwCLUrcTlz

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) April 9, 2024

Government

Student Loan Inflation, Here It Goes Again

Student Loan Inflation, Here It Goes Again

Via SchiffGold.com,

As the Democratic Party has shifted away from its traditional base of working-class…

As the Democratic Party has shifted away from its traditional base of working-class and middle-class Americans, to an increased reliance on college professors, students, and highly educated but low-paid professions, such as social workers, a new policy has risen to prominence: student loan forgiveness.

Borrowed money to advance your career or to study something you got pleasure from but don’t want to pay your loans back?

The new favorite argument by progressive policymakers is that you shouldn’t have to; the taxpayers can take the financial hit for you.

President Biden early in his term tried to deliver on that left-wing commitment by unilaterally canceling $400 billion in student loans. Biden claimed that the Higher Education Relief Opportunities For Students Act, which allowed the Secretary of Education to modify loans in response to national emergencies, combined with the pandemic coronavirus let him waive and modify student loans. The Supreme Court rejected his interpretation of that law.

Now, President Biden is back at it trying for another round of student loan forgiveness despite the mountains of criticism earlier actions took. Beyond the legal criticisms, policy experts have pointed out that student loan forgiveness is regressive because much of the debt is held by students who borrowed tens of thousands to go to graduate school, some of whom will go on to lucrative careers as doctors, dentists, lawyers, and more. Further, when debtors no longer devote part of their budget to repaying loans, this will free up their spending on other goods and services. The influx of new dollars chasing goods and services will make the prices increase in general. This is another inflation-pushing policy.

On Monday, April 8, Biden revealed the details of his new student loan forgiveness plan. It involves several planks. One plank would allow wiping away tens of thousands of accrued interest for borrowers and would extend forgiveness to relatively wealthy borrowers- couples making almost a quarter of a million dollars annually would be eligible. It would also reward borrowers who delayed paying back their loans, providing forgiveness to borrowers who still have not repaid their loans after 20 years for undergraduate students, or 25 years for undergraduate students.

The legal basis for this executive action is a law from the 1960s, the 1965 Higher Education Act, which as written allows the Secretary of Education to amend student loan terms.

When Senator Elizabeth Warren ran for president, she argued that this meant the Secretary of Education could be ordered by the president to forgive student loan borrowers en masse.

Perhaps the worst thing about these student loan forgiveness moves for the broader public is that even if courts limit or strike down some of these executive actions, student loan borrowers, to the extent that they are rational, should price in a now higher probability that at some point a Democratic president will try to bail out their loans, no matter how regressive such a policy might be.

These “rational expectations” that student loan borrowers now have an increased probability of a sudden windfall in the form of student loan forgiveness, should encourage them to save less, deprioritize paying off loans they voluntarily took, and increase their spending on consumption.

This increased consumption is rational already and encouraging additional dollars to chase the same supply of goods and services will drive inflation.

Another major downside of these student loan forgiveness plans is how they might encourage borrowers to run up higher tabs because they know there is some possibility that Biden or some other left-wing politician might waive their loans. While college students might reasonably borrow loans to pay for educational programs, each dollar borrowed with under market rates or forgiven by the federal government is fundamentally paid for by the rest of society. Students might also rationally borrow money they don’t strictly need for educational purposes to increase their standard of living, a practice that actually has sound economic logic and is known as consumption smoothing. However, to the extent this practice increases due to the risk of student loan forgiveness it will just be another factor propping up the painful Biden-esque levels of inflation we are already stuck with.

Until Congress changes the law to prevent unilateral executive action on student loan forgiveness or proponents of it pay a heavy political cost, inflation will be higher than it should be due to the specter of student loan forgiveness.

-

International3 weeks ago

International3 weeks agoParexel CEO to retire; CAR-T maker AffyImmune promotes business leader to chief executive

-

Spread & Containment4 weeks ago

Spread & Containment4 weeks agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Government3 days ago

Government3 days agoClimate-Con & The Media-Censorship Complex – Part 1

-

Spread & Containment21 hours ago

Spread & Containment21 hours agoFDA Finally Takes Down Ivermectin Posts After Settlement

-

Uncategorized1 week ago

Uncategorized1 week agoVaccinated People Show Long COVID-Like Symptoms With Detectable Spike Proteins: Preprint Study

-

Uncategorized4 days ago

Uncategorized4 days agoCan language models read the genome? This one decoded mRNA to make better vaccines.