Uncategorized

Taxing Billionaires Won’t Reduce Taxes For The Middle Class

Taxing Billionaires Won’t Reduce Taxes For The Middle Class

Authored by Daniel Lacalle,

In a world of populist policies, the notion of taxing…

In a world of populist policies, the notion of taxing billionaires to alleviate the financial burdens of the middle class stands as a tempting narrative. Advocates tout it as the quintessential solution to income inequality, promising a redistribution of wealth that lifts the masses from their fiscal woes. However, this narrative, so alluring in its simplicity, crumbles upon closer examination, revealing a multitude of complexities and pitfalls that belie its benefits.

Central to the fallacy of taxing billionaires lies a fundamental misunderstanding of the dynamics of government spending and deficits. Proponents of this approach often overlook the inconvenient truth that as most governments increase spending even when tax receipts rise, deficits soar to unprecedented heights, burdening future generations with a mountain of debt and always increasing taxes for the middle class.

Taxing the rich is the door that leads to more taxes for all of us. The case of the United States is evident. No tax revenue measure is going to wipe out an annual two trillion dollar deficit. Therefore, the government announces a large tax hike for the wealthy and disguises it with more taxes for everybody and higher inflation, which is a hidden tax.

The notion that taxing billionaires will miraculously alleviate this fiscal strain is akin to applying plaster to a gaping wound—it does not even provide temporary relief, and it fails to address the underlying malaise.

A seminal paper by Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi (2015) delves into the implications of government deficits on economic growth. The authors argue that persistent deficits not only crowd out private investment but also lead to higher interest rates, reduced confidence, and ultimately diminished economic growth. This underscores the importance of fiscal prudence in addressing long-term fiscal challenges and the evidence that tax hikes are not neutral.

Billionaires mostly hold their wealth in shares of their own companies. This is what is called “paper wealth.” However, they cannot sell those shares and if they lost them, their value would decline immediately.

The redistribution fallacy comes from three false ideas:

-

The first is the notion that billionaires do not pay taxes to begin with. The top one percent of income earners in the United States earned 22 percent of all income and paid 42 percent of all federal income.

-

The second error is believing that wealth is static—like a pie—and can be redistributed at will. Wealth is either created or destroyed. Confiscating the wealth of billionaires does not make the middle class or the poor richer. We should have learned that lesson from the numerous examples in history, from the French Revolution to the Soviet Union.

-

The third mistake is to believe that the economy is a sum-zero game where the wealth of one person is the loss of another. That is simply false because wealth is not “there.” It must be created through an exercise where all parties win in exchange for cooperation.

The world must strive to create more wealth, not limit those who generate it.

Consider the recent clamour for increased government intervention and spending, particularly in the wake of global crises. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic prompted governments all over the world to enact a flurry of fiscal stimuli, ostensibly intended to soften the blow of the economic fallout. Yet, as the dust settles, we find ourselves grappling not only with the immediate ramifications of increased government spending but also with the long-term consequences of ballooning deficits as well as persistent inflation.

Who came out as the loser of the redistribution and stimulus frenzy of the past decade? The middle class. It has been destroyed by persistent inflation created by printing money without control, rising debt and deficits and constantly bloating government size in the economy, which in turn creates two taxes for the middle class and the poor: inflation and rising indirect taxes.

Critics of this approach have long warned of the dangers of irresponsible government spending. Taxing billionaires will not stop this trend of excessive bureaucracy and irresponsible administration of public services; in fact, it may accelerate it, as we have seen in so many countries, and certainly will not reduce the tax wedge on ordinary citizens.

History is replete with cautionary tales of nations brought to their knees by unchecked fiscal excesses. From hyperinflation to sovereign debt crises, the ramifications of fiscal irresponsibility are manifold and far-reaching. And yet, in the face of mounting pressure to “tax the rich,” policymakers seem intent on repeating the mistakes of the past, heedless of the inevitable consequences.

But the fallacy of taxing billionaires extends beyond the realm of fiscal policy—it strikes at the very heart of economic prosperity. At its core, capitalism depends on investment, entrepreneurship, and innovation—all of which are at risk from excessive taxation. The narrative that vilifies billionaires as greedy hoarders of wealth overlooks their crucial role in driving economic growth and prosperity.

By focusing solely on redistributive measures, policymakers risk undermining the very foundations of prosperity upon which our economic system rests.

Moreover, the notion that taxing billionaires will somehow level the playing field and uplift the middle class is predicated on a flawed understanding of economic reality. In truth, the global mobility of capital renders such measures largely ineffective, as the ultra-wealthy can easily relocate to jurisdictions with more favourable tax regimes. This not only undermines the efficacy of taxing billionaires as a revenue-generating mechanism but also exacerbates the very inequalities it seeks to redress.

Indeed, the unintended consequences of excessively taxing the rich are manifold and far-reaching. From reduced investment and job creation to economic stagnation and decline, the repercussions of such policies are felt across society. And while the rhetoric of wealth redistribution may sound appealing in theory, the reality is far more sobering—a stagnant economy, diminished opportunities, and a dwindling standard of living for all.

So, where does this leave us? If taxing billionaires is not the panacea it purports to be, what alternatives exist to address income inequality and alleviate the burdens of the middle class? The answer lies not in punitive taxation but in prudent fiscal policy, targeted policies, and a renewed focus on fostering economic growth and prosperity for all.

Primarily, we must recognize that fiscal responsibility is not a luxury but a necessity. Governments must exercise restraint in their spending, prioritize efficiency and accountability, and resist the temptation to paper over fiscal deficits with ill-conceived tax hikes and money printing. Only through disciplined fiscal management can we hope to secure a prosperous future for generations to come.

Second, we must recognize the vital role that entrepreneurship and investment play in driving economic growth and prosperity. Rather than demonizing billionaires as the root of all evil, we should celebrate their contributions to society and create an environment that fosters innovation, entrepreneurship, and wealth creation. This means reducing regulatory barriers, incentivizing investment, and empowering individuals to pursue their entrepreneurial ambitions.

Finally, we must understand that opportunities provided to citizens, not the size of the government, are what define true progress. Rather than relying on the state to solve all our problems, we should empower individuals and communities to chart their own course to prosperity. This means investing in education, healthcare, and infrastructure, providing a safety net for those in need, and fostering a culture of self-reliance and personal responsibility.

In conclusion, the fallacy of taxing billionaires lies not in its intentions but in its execution. While the notion of redistributing wealth may sound appealing in theory, the reality is far more complex. By succumbing to the allure of punitive taxation, we risk stifling economic growth, undermining prosperity, and perpetuating the very inequalities we seek to redress. Only through prudent fiscal management, targeted interventions, and a renewed focus on fostering economic growth can we hope to build a future that is truly prosperous for all.

Socialism does not redistribute from the rich to the poor, but from the middle class to politicians.

The fallacy of massively taxing billionaires is another trick to promote socialism, which has never been about the redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor, but the redistribution of wealth from the middle class to politicians.

Uncategorized

Comments on February Employment Report

The headline jobs number in the February employment report was above expectations; however, December and January payrolls were revised down by 167,000 combined. The participation rate was unchanged, the employment population ratio decreased, and the …

Prime (25 to 54 Years Old) Participation

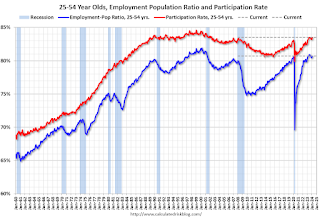

Since the overall participation rate is impacted by both cyclical (recession) and demographic (aging population, younger people staying in school) reasons, here is the employment-population ratio for the key working age group: 25 to 54 years old.

The 25 to 54 years old participation rate increased in February to 83.5% from 83.3% in January, and the 25 to 54 employment population ratio increased to 80.7% from 80.6% the previous month.

Average Hourly Wages

The graph shows the nominal year-over-year change in "Average Hourly Earnings" for all private employees from the Current Employment Statistics (CES).

The graph shows the nominal year-over-year change in "Average Hourly Earnings" for all private employees from the Current Employment Statistics (CES). Wage growth has trended down after peaking at 5.9% YoY in March 2022 and was at 4.3% YoY in February.

Part Time for Economic Reasons

From the BLS report:

From the BLS report:"The number of people employed part time for economic reasons, at 4.4 million, changed little in February. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs."The number of persons working part time for economic reasons decreased in February to 4.36 million from 4.42 million in February. This is slightly above pre-pandemic levels.

These workers are included in the alternate measure of labor underutilization (U-6) that increased to 7.3% from 7.2% in the previous month. This is down from the record high in April 2020 of 23.0% and up from the lowest level on record (seasonally adjusted) in December 2022 (6.5%). (This series started in 1994). This measure is above the 7.0% level in February 2020 (pre-pandemic).

Unemployed over 26 Weeks

This graph shows the number of workers unemployed for 27 weeks or more.

This graph shows the number of workers unemployed for 27 weeks or more. According to the BLS, there are 1.203 million workers who have been unemployed for more than 26 weeks and still want a job, down from 1.277 million the previous month.

This is close to pre-pandemic levels.

Job Streak

| Headline Jobs, Top 10 Streaks | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year Ended | Streak, Months | |

| 1 | 2019 | 100 |

| 2 | 1990 | 48 |

| 3 | 2007 | 46 |

| 4 | 1979 | 45 |

| 5 | 20241 | 38 |

| 6 tie | 1943 | 33 |

| 6 tie | 1986 | 33 |

| 6 tie | 2000 | 33 |

| 9 | 1967 | 29 |

| 10 | 1995 | 25 |

| 1Currrent Streak | ||

Summary:

The headline monthly jobs number was above consensus expectations; however, December and January payrolls were revised down by 167,000 combined. The participation rate was unchanged, the employment population ratio decreased, and the unemployment rate was increased to 3.9%. Another solid report.

Uncategorized

Immune cells can adapt to invading pathogens, deciding whether to fight now or prepare for the next battle

When faced with a threat, T cells have the decision-making flexibility to both clear out the pathogen now and ready themselves for a future encounter.

How does your immune system decide between fighting invading pathogens now or preparing to fight them in the future? Turns out, it can change its mind.

Every person has 10 million to 100 million unique T cells that have a critical job in the immune system: patrolling the body for invading pathogens or cancerous cells to eliminate. Each of these T cells has a unique receptor that allows it to recognize foreign proteins on the surface of infected or cancerous cells. When the right T cell encounters the right protein, it rapidly forms many copies of itself to destroy the offending pathogen.

Importantly, this process of proliferation gives rise to both short-lived effector T cells that shut down the immediate pathogen attack and long-lived memory T cells that provide protection against future attacks. But how do T cells decide whether to form cells that kill pathogens now or protect against future infections?

We are a team of bioengineers studying how immune cells mature. In our recently published research, we found that having multiple pathways to decide whether to kill pathogens now or prepare for future invaders boosts the immune system’s ability to effectively respond to different types of challenges.

Fight or remember?

To understand when and how T cells decide to become effector cells that kill pathogens or memory cells that prepare for future infections, we took movies of T cells dividing in response to a stimulus mimicking an encounter with a pathogen.

Specifically, we tracked the activity of a gene called T cell factor 1, or TCF1. This gene is essential for the longevity of memory cells. We found that stochastic, or probabilistic, silencing of the TCF1 gene when cells confront invading pathogens and inflammation drives an early decision between whether T cells become effector or memory cells. Exposure to higher levels of pathogens or inflammation increases the probability of forming effector cells.

Surprisingly, though, we found that some effector cells that had turned off TCF1 early on were able to turn it back on after clearing the pathogen, later becoming memory cells.

Through mathematical modeling, we determined that this flexibility in decision making among memory T cells is critical to generating the right number of cells that respond immediately and cells that prepare for the future, appropriate to the severity of the infection.

Understanding immune memory

The proper formation of persistent, long-lived T cell memory is critical to a person’s ability to fend off diseases ranging from the common cold to COVID-19 to cancer.

From a social and cognitive science perspective, flexibility allows people to adapt and respond optimally to uncertain and dynamic environments. Similarly, for immune cells responding to a pathogen, flexibility in decision making around whether to become memory cells may enable greater responsiveness to an evolving immune challenge.

Memory cells can be subclassified into different types with distinct features and roles in protective immunity. It’s possible that the pathway where memory cells diverge from effector cells early on and the pathway where memory cells form from effector cells later on give rise to particular subtypes of memory cells.

Our study focuses on T cell memory in the context of acute infections the immune system can successfully clear in days, such as cold, the flu or food poisoning. In contrast, chronic conditions such as HIV and cancer require persistent immune responses; long-lived, memory-like cells are critical for this persistence. Our team is investigating whether flexible memory decision making also applies to chronic conditions and whether we can leverage that flexibility to improve cancer immunotherapy.

Resolving uncertainty surrounding how and when memory cells form could help improve vaccine design and therapies that boost the immune system’s ability to provide long-term protection against diverse infectious diseases.

Kathleen Abadie was funded by a NSF (National Science Foundation) Graduate Research Fellowships. She performed this research in affiliation with the University of Washington Department of Bioengineering.

Elisa Clark performed her research in affiliation with the University of Washington (UW) Department of Bioengineering and was funded by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (NSF-GRFP) and by a predoctoral fellowship through the UW Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine (ISCRM).

Hao Yuan Kueh receives funding from the National Institutes of Health.

stimulus covid-19 yuan vaccine stimulusUncategorized

Stock indexes are breaking records and crossing milestones – making many investors feel wealthier

The S&P 500 topped 5,000 on Feb. 9, 2024, for the first time. The Dow Jones Industrial Average will probably hit a new big round number soon t…

The S&P 500 stock index topped 5,000 for the first time on Feb. 9, 2024, exciting some investors and garnering a flurry of media coverage. The Conversation asked Alexander Kurov, a financial markets scholar, to explain what stock indexes are and to say whether this kind of milestone is a big deal or not.

What are stock indexes?

Stock indexes measure the performance of a group of stocks. When prices rise or fall overall for the shares of those companies, so do stock indexes. The number of stocks in those baskets varies, as does the system for how this mix of shares gets updated.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, also known as the Dow, includes shares in the 30 U.S. companies with the largest market capitalization – meaning the total value of all the stock belonging to shareholders. That list currently spans companies from Apple to Walt Disney Co.

The S&P 500 tracks shares in 500 of the largest U.S. publicly traded companies.

The Nasdaq composite tracks performance of more than 2,500 stocks listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange.

The DJIA, launched on May 26, 1896, is the oldest of these three popular indexes, and it was one of the first established.

Two enterprising journalists, Charles H. Dow and Edward Jones, had created a different index tied to the railroad industry a dozen years earlier. Most of the 12 stocks the DJIA originally included wouldn’t ring many bells today, such as Chicago Gas and National Lead. But one company that only got booted in 2018 had stayed on the list for 120 years: General Electric.

The S&P 500 index was introduced in 1957 because many investors wanted an option that was more representative of the overall U.S. stock market. The Nasdaq composite was launched in 1971.

You can buy shares in an index fund that mirrors a particular index. This approach can diversify your investments and make them less prone to big losses.

Index funds, which have only existed since Vanguard Group founder John Bogle launched the first one in 1976, now hold trillions of dollars .

Why are there so many?

There are hundreds of stock indexes in the world, but only about 50 major ones.

Most of them, including the Nasdaq composite and the S&P 500, are value-weighted. That means stocks with larger market values account for a larger share of the index’s performance.

In addition to these broad-based indexes, there are many less prominent ones. Many of those emphasize a niche by tracking stocks of companies in specific industries like energy or finance.

Do these milestones matter?

Stock prices move constantly in response to corporate, economic and political news, as well as changes in investor psychology. Because company profits will typically grow gradually over time, the market usually fluctuates in the short term, while increasing in value over the long term.

The DJIA first reached 1,000 in November 1972, and it crossed the 10,000 mark on March 29, 1999. On Jan. 22, 2024, it surpassed 38,000 for the first time. Investors and the media will treat the new record set when it gets to another round number – 40,000 – as a milestone.

The S&P 500 index had never hit 5,000 before. But it had already been breaking records for several weeks.

Because there’s a lot of randomness in financial markets, the significance of round-number milestones is mostly psychological. There is no evidence they portend any further gains.

For example, the Nasdaq composite first hit 5,000 on March 10, 2000, at the end of the dot-com bubble.

The index then plunged by almost 80% by October 2002. It took 15 years – until March 3, 2015 – for it return to 5,000.

By mid-February 2024, the Nasdaq composite was nearing its prior record high of 16,057 set on Nov. 19, 2021.

Index milestones matter to the extent they pique investors’ attention and boost market sentiment.

Investors afflicted with a fear of missing out may then invest more in stocks, pushing stock prices to new highs. Chasing after stock trends may destabilize markets by moving prices away from their underlying values.

When a stock index passes a new milestone, investors become more aware of their growing portfolios. Feeling richer can lead them to spend more.

This is called the wealth effect. Many economists believe that the consumption boost that arises in response to a buoyant stock market can make the economy stronger.

Is there a best stock index to follow?

Not really. They all measure somewhat different things and have their own quirks.

For example, the S&P 500 tracks many different industries. However, because it is value-weighted, it’s heavily influenced by only seven stocks with very large market values.

Known as the “Magnificent Seven,” shares in Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla now account for over one-fourth of the S&P 500’s value. Nearly all are in the tech sector, and they played a big role in pushing the S&P across the 5,000 mark.

This makes the index more concentrated on a single sector than it appears.

But if you check out several stock indexes rather than just one, you’ll get a good sense of how the market is doing. If they’re all rising quickly or breaking records, that’s a clear sign that the market as a whole is gaining.

Sometimes the smartest thing is to not pay too much attention to any of them.

For example, after hitting record highs on Feb. 19, 2020, the S&P 500 plunged by 34% in just 23 trading days due to concerns about what COVID-19 would do to the economy. But the market rebounded, with stock indexes hitting new milestones and notching new highs by the end of that year.

Panicking in response to short-term market swings would have made investors more likely to sell off their investments in too big a hurry – a move they might have later regretted. This is why I believe advice from the immensely successful investor and fan of stock index funds Warren Buffett is worth heeding.

Buffett, whose stock-selecting prowess has made him one of the world’s 10 richest people, likes to say “Don’t watch the market closely.”

If you’re reading this because stock prices are falling and you’re wondering if you should be worried about that, consider something else Buffett has said: “The light can at any time go from green to red without pausing at yellow.”

And the opposite is true as well.

Alexander Kurov does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

dow jones sp 500 nasdaq stocks covid-19-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges