How online markets are helping local stores survive COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen a rise in digital localism — consumers using online local sites to buy and supply goods. Do platforms born during COVID-19 have a chance of survival?

Retail giants like Amazon are blurring the boundaries of consumption. But thanks to platforms that link online consumption to local interests, the desire to buy local, a trend fuelled by the COVID-19 pandemic, is now giving rise to a new phenomenon known as “digital localism.”

While the pandemic has resulted in border closures and an increased desire to localize production and use supply chains that are close to home, large platforms like Amazon have been criticized for cashing in on the economic misfortune for small local businesses brought about by the crisis.

In Québec, this spawned the creation of new platforms to sell local goods, such as Le Panier Bleu, Ma Zone Québec, Boomerang, Inc. and J'achète au Lac, a site for purchasing local goods in the province’s Lac St-Jean region.

A local e-commerce platform for shopping malls also sprung up, as well as Eva, a rideshare co-operative platform that works with taxi companies and gives drivers more control over the business.

These new companies are bringing back meaning to consumption and production. And in these times of transition, aren’t we all looking for ways to add more meaning to our lives?

The era of the consumer-supplier

Whether you want to carpool using the Eva platform, trade goods with someone on Kijiji, participate in a crowdfunding effort on Ulule or do business on a site like Dvore, it’s the consumer-supplier concept that’s making this transition possible.

Consumption methods have become increasingly divorced from production since the beginning of the 20th century. Consumers have become strictly buyers. However, new concepts like collaborative consumption, the sharing economy and crowd-based capitalism are now mixing the modes of consumption and production.

The passive consumer is being replaced by an active consumer who takes on the role of supplier, volunteer or even partner.

For example, by using NousRire (a play on the French “nourir”, “to feed”), a Québec-based bulk-purchasing group for eco-responsible food sites, clients become both suppliers and volunteers. In other words, they are partners in the organization.

Similar changes are taking place in the world of large-scale distribution. Examples include IKEA’s “second life for furniture” service, and Marks & Spencer’s shwopping (a contraction of shopping and swapping), a service that allows shoppers to donate used clothing in boxes located in the British retailer’s stores.

The term “collaborative consumption” has been used to describe this new trend of consumers who, thanks to these different platforms and applications, are also serving as suppliers. The same concept applies to Facebook Marketplace, Kijiji, InstaCart and VarageSale.

Not just about saving money

What’s motivating consumers to adopt these new practices?

While buyers and suppliers have both financial and utilitarian goals, suppliers in this model can also be motivated by factors that go beyond pure financial gain. Those motivations may include financial constraints (debt, liquidity problems), a desire to socialize with others, to contribute to society or simple altruism.

In addition to the aforementioned trading platforms, sites like Coursera offer individuals training and advice resources. For outsourcing tasks, people can turn to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

In health care, a transition towards digital care is underway that is making it possible to better distribute resources and allows people to offer advice and services through online forums, groups or patient communities.

Read more: Good governance is the missing prescription for better digital health care

Democratizing markets

The financial sector has also become more democratic. Crowd-funding platforms such as Ulule make it possible for individuals to donate or invest in projects carried out by other parties, while platforms like eToro make investing in financial markets more of a democratic process.

These platforms allow individuals to revitalize local economies by redirecting capital toward areas that are typically neglected by public or private investment.

Cryptocurrency and blockchain are also interesting examples. Thousands of cryptocurrency systems like Bitcoin are operating right now that involve cryptocurrency miners replacing central banks. Facebook’s Diem blockchain-based payment system project suggests that there is a “total digital ecosystem” emerging: a dematerialized and demonetized society entirely centred on individuals.

Read more: Financial professions must pivot to stave off technological extinction

In 2016, India even tried to set up a cashless society. The policy had an impact on practices specific to emerging countries, including cash on delivery, which was transformed into payment on delivery. It’s hard to say if this is good news or bad. On one hand, collaborative transactions, which are often informal, are getting easier to perform. On the other, they are totally traceable and taxable.

A controversial economy

The collaborative economy is probably the most visible, well-documented and disruptive example of the ongoing marketplace transformation. Hotel owners complain about Airbnb and taxi businesses about Uber because, in principle, any individual can now supply lodging or transport for a fee. These debates in Québec have resulted in laws that are more accommodating to the new players. Those laws have, in turn, helped new platforms boost their activities.

This change has allowed authorities to transfer some of the responsibility for public services to the private sector. In public transportation, the availability of carpooling services could compensate for shortages in public transit. Citizens appreciate these practices because they satisfy their needs, maximize the use of dormant resources, provide better access to resources for the poor and reduce unemployment.

However, it is still unclear whether, by turning suppliers into “entrepreneurs,” these platforms are reinventing working conditions or damaging them given the many issues facing precarious workers.

Read more: California's gig worker battle reveals the abuses of precarious work in Canada too

An illusion of power?

It’s essential to understand the impact that the algorithms used by these platforms are having on governance, questions of inclusion and user rights. The exponential amount of data generated by the platforms has increased large companies’ ability to identify the needs of their users quickly, and evaluate their payment capabilities precisely.

These capacities could lead to discriminatory practices. In addition, platforms are notoriously opaque about their pricing practices: they often customize and adjust prices in real time for each user.

Finally, since the collaborative economy is monopolized by technological giants, it’s less likely that smaller platforms will emerge, let alone survive. In short, by becoming a supplier — either as an entrepreneur or self-employed worker or through a flexible work schedule — consumers may only be gaining an illusion of power when they’re still in the service of mega-platforms.

Will digital localism be able to make its place in this world? Will platforms born during the COVID-19 pandemic in a bid to support local economies have any chance of surviving in the longer term?

According to a case study of small and medium-sized car-sharing platforms in China, the only way smaller platforms can hope to survive is by addressing needs that are not being met by the giants: leveraging a particular customer segment, type of partner, value proposition or their cost structure and revenue stream.

Nonetheless, recent developments in digital technologies are clearly giving individuals more ways to contribute. This digital transition, already well underway, has accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic and is unlikely to stop soon.

Myriam Ertz is part of the Groupement Des Universitaires (DU) and has obtained research grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Société et Culture (FRQSC), the Fondation de l'UQAC (FUQAC), and the Fonds de Développement Académique du Réseau (FODAR) of the Université du Québec.

Imen Latrous receives funding from Université du Québec à Chicoutimi.

Damien Hallegatte and Julien Bousquet do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

cryptocurrency bitcoin blockchain link pandemic covid-19Spread & Containment

The Coming Of The Police State In America

The Coming Of The Police State In America

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

The National Guard and the State Police are now…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

The National Guard and the State Police are now patrolling the New York City subway system in an attempt to do something about the explosion of crime. As part of this, there are bag checks and new surveillance of all passengers. No legislation, no debate, just an edict from the mayor.

Many citizens who rely on this system for transportation might welcome this. It’s a city of strict gun control, and no one knows for sure if they have the right to defend themselves. Merchants have been harassed and even arrested for trying to stop looting and pillaging in their own shops.

The message has been sent: Only the police can do this job. Whether they do it or not is another matter.

Things on the subway system have gotten crazy. If you know it well, you can manage to travel safely, but visitors to the city who take the wrong train at the wrong time are taking grave risks.

In actual fact, it’s guaranteed that this will only end in confiscating knives and other things that people carry in order to protect themselves while leaving the actual criminals even more free to prey on citizens.

The law-abiding will suffer and the criminals will grow more numerous. It will not end well.

When you step back from the details, what we have is the dawning of a genuine police state in the United States. It only starts in New York City. Where is the Guard going to be deployed next? Anywhere is possible.

If the crime is bad enough, citizens will welcome it. It must have been this way in most times and places that when the police state arrives, the people cheer.

We will all have our own stories of how this came to be. Some might begin with the passage of the Patriot Act and the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security in 2001. Some will focus on gun control and the taking away of citizens’ rights to defend themselves.

My own version of events is closer in time. It began four years ago this month with lockdowns. That’s what shattered the capacity of civil society to function in the United States. Everything that has happened since follows like one domino tumbling after another.

It goes like this:

1) lockdown,

2) loss of moral compass and spreading of loneliness and nihilism,

3) rioting resulting from citizen frustration, 4) police absent because of ideological hectoring,

5) a rise in uncontrolled immigration/refugees,

6) an epidemic of ill health from substance abuse and otherwise,

7) businesses flee the city

8) cities fall into decay, and that results in

9) more surveillance and police state.

The 10th stage is the sacking of liberty and civilization itself.

It doesn’t fall out this way at every point in history, but this seems like a solid outline of what happened in this case. Four years is a very short period of time to see all of this unfold. But it is a fact that New York City was more-or-less civilized only four years ago. No one could have predicted that it would come to this so quickly.

But once the lockdowns happened, all bets were off. Here we had a policy that most directly trampled on all freedoms that we had taken for granted. Schools, businesses, and churches were slammed shut, with various levels of enforcement. The entire workforce was divided between essential and nonessential, and there was widespread confusion about who precisely was in charge of designating and enforcing this.

It felt like martial law at the time, as if all normal civilian law had been displaced by something else. That something had to do with public health, but there was clearly more going on, because suddenly our social media posts were censored and we were being asked to do things that made no sense, such as mask up for a virus that evaded mask protection and walk in only one direction in grocery aisles.

Vast amounts of the white-collar workforce stayed home—and their kids, too—until it became too much to bear. The city became a ghost town. Most U.S. cities were the same.

As the months of disaster rolled on, the captives were let out of their houses for the summer in order to protest racism but no other reason. As a way of excusing this, the same public health authorities said that racism was a virus as bad as COVID-19, so therefore it was permitted.

The protests had turned to riots in many cities, and the police were being defunded and discouraged to do anything about the problem. Citizens watched in horror as downtowns burned and drug-crazed freaks took over whole sections of cities. It was like every standard of decency had been zapped out of an entire swath of the population.

Meanwhile, large checks were arriving in people’s bank accounts, defying every normal economic expectation. How could people not be working and get their bank accounts more flush with cash than ever? There was a new law that didn’t even require that people pay rent. How weird was that? Even student loans didn’t need to be paid.

By the fall, recess from lockdown was over and everyone was told to go home again. But this time they had a job to do: They were supposed to vote. Not at the polling places, because going there would only spread germs, or so the media said. When the voting results finally came in, it was the absentee ballots that swung the election in favor of the opposition party that actually wanted more lockdowns and eventually pushed vaccine mandates on the whole population.

The new party in control took note of the large population movements out of cities and states that they controlled. This would have a large effect on voting patterns in the future. But they had a plan. They would open the borders to millions of people in the guise of caring for refugees. These new warm bodies would become voters in time and certainly count on the census when it came time to reapportion political power.

Meanwhile, the native population had begun to swim in ill health from substance abuse, widespread depression, and demoralization, plus vaccine injury. This increased dependency on the very institutions that had caused the problem in the first place: the medical/scientific establishment.

The rise of crime drove the small businesses out of the city. They had barely survived the lockdowns, but they certainly could not survive the crime epidemic. This undermined the tax base of the city and allowed the criminals to take further control.

The same cities became sanctuaries for the waves of migrants sacking the country, and partisan mayors actually used tax dollars to house these invaders in high-end hotels in the name of having compassion for the stranger. Citizens were pushed out to make way for rampaging migrant hordes, as incredible as this seems.

But with that, of course, crime rose ever further, inciting citizen anger and providing a pretext to bring in the police state in the form of the National Guard, now tasked with cracking down on crime in the transportation system.

What’s the next step? It’s probably already here: mass surveillance and censorship, plus ever-expanding police power. This will be accompanied by further population movements, as those with the means to do so flee the city and even the country and leave it for everyone else to suffer.

As I tell the story, all of this seems inevitable. It is not. It could have been stopped at any point. A wise and prudent political leadership could have admitted the error from the beginning and called on the country to rediscover freedom, decency, and the difference between right and wrong. But ego and pride stopped that from happening, and we are left with the consequences.

The government grows ever bigger and civil society ever less capable of managing itself in large urban centers. Disaster is unfolding in real time, mitigated only by a rising stock market and a financial system that has yet to fall apart completely.

Are we at the middle stages of total collapse, or at the point where the population and people in leadership positions wise up and decide to put an end to the downward slide? It’s hard to know. But this much we do know: There is a growing pocket of resistance out there that is fed up and refuses to sit by and watch this great country be sacked and taken over by everything it was set up to prevent.

Government

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate…

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate iron levels in their blood due to a COVID-19 infection could be at greater risk of long COVID.

A new study indicates that problems with iron levels in the bloodstream likely trigger chronic inflammation and other conditions associated with the post-COVID phenomenon. The findings, published on March 1 in Nature Immunology, could offer new ways to treat or prevent the condition.

Long COVID Patients Have Low Iron Levels

Researchers at the University of Cambridge pinpointed low iron as a potential link to long-COVID symptoms thanks to a study they initiated shortly after the start of the pandemic. They recruited people who tested positive for the virus to provide blood samples for analysis over a year, which allowed the researchers to look for post-infection changes in the blood. The researchers looked at 214 samples and found that 45 percent of patients reported symptoms of long COVID that lasted between three and 10 months.

In analyzing the blood samples, the research team noticed that people experiencing long COVID had low iron levels, contributing to anemia and low red blood cell production, just two weeks after they were diagnosed with COVID-19. This was true for patients regardless of age, sex, or the initial severity of their infection.

According to one of the study co-authors, the removal of iron from the bloodstream is a natural process and defense mechanism of the body.

But it can jeopardize a person’s recovery.

“When the body has an infection, it responds by removing iron from the bloodstream. This protects us from potentially lethal bacteria that capture the iron in the bloodstream and grow rapidly. It’s an evolutionary response that redistributes iron in the body, and the blood plasma becomes an iron desert,” University of Oxford professor Hal Drakesmith said in a press release. “However, if this goes on for a long time, there is less iron for red blood cells, so oxygen is transported less efficiently affecting metabolism and energy production, and for white blood cells, which need iron to work properly. The protective mechanism ends up becoming a problem.”

The research team believes that consistently low iron levels could explain why individuals with long COVID continue to experience fatigue and difficulty exercising. As such, the researchers suggested iron supplementation to help regulate and prevent the often debilitating symptoms associated with long COVID.

“It isn’t necessarily the case that individuals don’t have enough iron in their body, it’s just that it’s trapped in the wrong place,” Aimee Hanson, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge who worked on the study, said in the press release. “What we need is a way to remobilize the iron and pull it back into the bloodstream, where it becomes more useful to the red blood cells.”

The research team pointed out that iron supplementation isn’t always straightforward. Achieving the right level of iron varies from person to person. Too much iron can cause stomach issues, ranging from constipation, nausea, and abdominal pain to gastritis and gastric lesions.

1 in 5 Still Affected by Long COVID

COVID-19 has affected nearly 40 percent of Americans, with one in five of those still suffering from symptoms of long COVID, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Long COVID is marked by health issues that continue at least four weeks after an individual was initially diagnosed with COVID-19. Symptoms can last for days, weeks, months, or years and may include fatigue, cough or chest pain, headache, brain fog, depression or anxiety, digestive issues, and joint or muscle pain.

Uncategorized

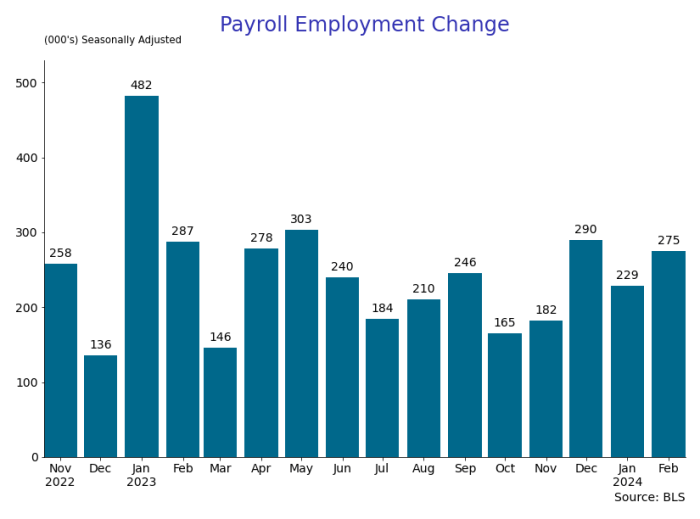

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemployment-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges