Uncategorized

A Response To A Question About Post-Keynesian Interest Rate Theories (…And A Rant)

I got a question about references for post-Keynesian theories of interest rates. My answer to this has a lot of levels, and eventually turns into a rant about modern academia. Since I do not want a good rant to go to waste, I will spell it out here. Lo…

I got a question about references for post-Keynesian theories of interest rates. My answer to this has a lot of levels, and eventually turns into a rant about modern academia. Since I do not want a good rant to go to waste, I will spell it out here. Long-time readers may have seen portions of this rant before, but my excuse is that I have a lot of new readers.

(I guess I can put a plug in for my book Interest Rate Cycles: An Introduction which covers a variety of topics around interest rates.)

References (Books)

For reasons that will become apparent later, I do not have particular favourites among post-Keynesian theories of interest rates. For finding references, I would give the following three textbooks as starting points. Note that as academic books, they are pricey. However, starting with textbooks is more efficient from a time perspective than trawling around on the internet looking for free articles.

Mitchell, William, L. Randall Wray, and Martin Watts. Macroeconomics. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019. Notes: This is an undergraduate-level textbook, and references are very limited. For the person who originally asked the question, this is perhaps not the best fit.

Lavoie, Marc. Post-Keynesian economics: new foundations. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2022. This is an introductory graduate level textbook, and is a survey of PK theory. Chuck full o’ citations.

Godley, Wynne, and Marc Lavoie. Monetary economics: an integrated approach to credit, money, income, production and wealth. Springer, 2006. This book is an introduction to stock-flow consistent models, and is probably the best starting point for post-Keynesian economics for someone with mathematical training.

Why Books?

If you have access to a research library and you have at least some knowledge of the field one can do a literature survey by going nuts chasing down citations from other papers. I did my doctorate in the Stone Age, and I had a stack of several hundred photocopied papers related to my thesis sprawled across on my desk1, and I periodically spent the afternoon camped out in the journal section of the engineering library reading and photocopying the interesting ones.

If you do not have access to such a library, it is painful getting articles. And if you do not know the field, you are making a grave mistake to rely on articles to get a survey of the field.

In order to get published, authors have no choice but to hype up their own work. Ground-breaking papers have cushion to be modest, but more than 90% of academic papers ought never have to been published, so they have no choice but to self-hype.

Academic politics skews what articles are cited. Also, alternative approaches need to be minimised in order handing ammunition to reviewers looking to reject the paper.

The adversarial review process makes it safer to avoid anything remotely controversial in areas of the text that are not part of what allegedly makes it novel.

My points here might sound cynical, but they just are what happens if you apply any minimal intellectual standards to modern academic output. Academics have to churn out papers; the implication is that the papers cannot all be winners.

The advantage of an “introductory post-graduate” textbook is that the author is doing the survey of a field, and it is exceedingly unlikely that they produced all the research being surveyed. This allows them to take a “big picture” view of the field, without worries about originality. Academic textbooks are not cheap, but if you value your time (or have an employer to pick up the tab), they are the best starting point.

My Background

One of my ongoing jobs back when I was an employee was doing donkey work for economists. To the extent that I had any skills, I was a “model builder.” And so I was told to go off and build models according to various specifications.

Over the years, I developed hundreds (possibly thousands) of “reduced order” models that related economic variables to interest rates, based on conventional and somewhat heterodox thinking. (“Reduced order” has a technical definition, I am using the term somewhat loosely. “Relatively simple models with a limited number of inputs and outputs” is what I mean.) Of course, I also mucked around with the data and models on my own initiative.

To summarise my thinking, I am not greatly impressed with the ability of reduced order models to tell us about the effect of interest rates. And it is not hard to prove me wrong — just come up with such a reduced form model. The general lack of agreement on such a model is a rather telling point.

“Conventional” Thinking On Interest Rates

The conventional thinking on interest rates is that if inflation is too high, the central bank hikes the policy rate to slow it. The logic is that if interest rates go up, growth or inflation (or both) falls. This conventional thinking is widespread, and even many post-Keynesians agree with it.

Although there is widespread consensus about that story, the problem shows up as soon as you want to put numbers to it. An interest rate is a number. How high does it have to be to slow inflation?

Back in the 1990s, there were a lot of people who argued that the magic cut off point for the effect of the real interest rate was the “potential trend growth rate” of the economy (working age population growth plus productivity growth). The beauty of that theory is that it gave a testable prediction. The minor oopsie was that it did not in fact work.

So we were stuck with what used to be called the “neutral interest rate” — now denoted r* — which moves around (a lot). The level of r* is estimated with a suitably complex statistical process. The more complex the estimation the better — since you need something to distract from the issue of non-falsifiability. If you use a model to calibrate r* on historical data, by definition your model will “predict” historical data when you compare the actual real policy rate versus your r* estimate. The problem is that if r* keeps moving around — it does not tell you much about the future. For example, is a real interest rate of 2% too low to cause inflation to drop? Well, just set it at 2% and see whether it drops! The problem is that you only find out later.

Post-Keynesian Interest Rate Models

If you read the Marc Lavoie “New Foundations” text, you will see that what defines “post-Keynesian” economics is difficult. There are multiple schools of thought (possibly with some “schools” being one individual) — one of which he labels “Post-Keynesian” (capital P) that does not consider anybody else to be “post-Keynesian.” I take what Lavoie labels as the “broad tent” view, and accept that PK economics is a mix of schools of thought that have some similarities — but still have theoretical disagreements.

Interest rate theories is one of big areas of disagreement. This is especially true after the rise of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

MMT is a relatively recent offshoot of the other PK schools of thought. What distinguished MMT is that the founders wanted to come up with an internally consistent story that could be used to convince outsiders to act more sensibly. The effect of interest rates on the economy was one place where MMTers have a major disagreement with others in the broad PK camp, and even the MMTers have somewhat varied positions.

The best way to summarise the consensus MMT position is that the effect of interest rates on the economy are ambiguous, and weaker than conventional beliefs. A key point is that interest payments to the private sector are a form of income, and thus a weak stimulus. (The mainstream awkwardly tries to incorporate this by bringing up “fiscal dominance” — but fiscal dominance is just decried as a bad thing, and is not integrated into other models.) Since this stimulus runs counter to the conventional belief that interest rates slow the economy, one can argue that conventional thinking is backwards. (Warren Mosler emphases this, other MMT proponents lean more towards “ambiguous.”)

For what it is worth, “ambiguous” fits my experience of churning out interest rate models, so that is good enough for me. I think that if we want to dig, we need to look at the interest rate sensitivity of sectors, like housing. The key is that we are not looking at an aggregated model of the economy — once you have multiple sectors, we can get ambiguous effects.

What about the Non-MMT Post-Keynesians?

The fratricidal fights between MMT economists and selected other post-Keynesians (not all, but some influential ones) was mainly fought over the role of floating exchange rates and fiscal policy, but interest rates showed up. Roughly speaking, they all agreed that neoclassicals are wrong about interest rates. Nevertheless, there are divergences on how effective interest rates are.

I would divide the post-Keynesian interest rate literature into a few segments.

Empirical analysis of the effects of interest rates, mainly on fixed investment.

Fairly basic toy models that supposedly tell us about the effect of interest rates. (“Liquidity preference” models that allegedly tell us about bond yields is one example. I think that such models are a waste of time — rate expectations factor into real world fixed income trading.)

Analysis of why conventional thinking about interest rates is incorrect because it does not take into account some factors.

Analysis of who said what about interest rates (particularly Keynes).

From an outsiders standpoint, the problem is that even if the above topics are interesting, the standard mode of exposition is to jumble these areas of interest into a long literary piece. My experience is that unless I am already somewhat familiar with the topics discussed, I could not follow the logical structure of arguments.

The conclusions drawn varied by economist. Some older ones seem indistinguishable from 1960s era Keynesian economists in their reliance on toy models with a couple of supply/demand curves.

I found the strongest part of this literature was the essentially empirical question: do interest rates affect behaviour in the ways suggested by classical/neoclassical models? The rest of the literature is not structured in a way that I am used to, and so I have a harder time discussing it.

Appendix: Academic Dysfunction

I will close with a rant about the state of modern academia, which also explains why I am not particularly happy with wading through relatively recent (post-1970!) journal articles trying to do a literature search. I am repeating old rant contents here, but I am tacking on new material at the end (which is exactly the behaviour I complain about!).

The structural problem with academia was the rise of the “publish or perish” culture. Using quantitative performance metrics — publications, citation counts — was an antidote to the dangers of mediocrity created by “old boy networks” handing out academic posts. The problem is that the quantitative metric changes behaviour (Goodhart’s Law). Everybody wants their faculty to be above average — and sets their target publication counts accordingly.

This turns academic publishing into a game. It was possible to produce good research, but the trick was to get as many articles out of it as possible. Some researchers are able to produce a deluge of good papers — partly because they have done a good job of developing students and colleagues to act as co-authors. Most are only able to get a few ideas out. Rather than forcing people to produce and referee papers that nobody actually wants to read, everybody should just lower expected publication count standards. However, that sounds bad, so here we are. I left academia because spending the rest of my life churning out articles that I know nobody should read was not attractive.

These problems affect all of academia. (One of the advantages of the college system of my grad school is that it drove you to socialise with grad students in other fields, and not just your own group.) The effects are least bad in fields where there are very high publication standards, or the field is vibrant and new, and there is a lot of space for new useful research.

Pure mathematics is (was?) an example of a field with high publication standards. By definition, there are limited applications of the work, so it attracts less funding. There are less positions, and so the members of the field could be very selective. They policed their journals with their wacky notions of “mathematical elegance,” and this was enough to keep people like me out.

In applied fields (engineering, applied mathematics), publications cannot be policed based on “elegance.” Instead, they are supposed to be “useful.” The way the field decided to measure usefulness was to see whether it could attract industrial partners funding the research. Although one might decry the “corporate influence” on academia, it helps keep applied research on track.

The problem is in areas with no recent theoretical successes. There is no longer an objective way to measure a “good” paper. What happens instead is that papers are published on the basis that they continue the framework of what is seen as a “good” paper in the past.

My academic field of expertise was in such an area. I realised that I had to either get into a new research area that had useful applications — or get out (which I did). I have no interest in the rest of economics, but it is safe to say that macroeconomics (across all fields of thought) has had very few theoretical successes for a very long time. Hence, there is little to stop the degeneration of the academic literature.

Neoclassical macroeconomics has the most people publishing in it, and gets the lion share of funding. Their strange attachment to 1960s era optimal control theory means that the publication standards are closest to what I was used to. The beauty of the mathematical approach to publications is that originality is theoretically easy to assess: has anyone proved this theorem before? You can ignore the textual blah-blah-blah and jump straight to the mathematical meat.

Unfortunately, if the models are useless in practice, this methodology just leaves you open to the problem that there is an infinite number of theorems about different models to be proven. Add in a large accepted gap between the textual representations of what a theorem suggests and what the mathematics does, you end up with a field that has an infinite capacity to produce useless models with irrelevant differences between them. And unlike engineering firms that either go bankrupt or dump failed technology research, researchers at central banks tend to fail upwards. Ask yourself this: if the entire corpus of post-1970 macroeconomic research had been ritually burned, would it have really mattered to how the Fed reacted to the COVID pandemic? (“Oh no, crisis! Cut rates! Oops, inflation! Hike rates!”)

More specifically, neoclassicals have an array of “good” simple macro models that they teach and use as “acceptable” models for future papers. However, those “good” models can easily contradict each other. E.g., use an OLG model to “prove” that debt is burden on future generations, use other models to “prove” that “MMT says nothing new.” Until a model is developed that is actually useful, they are doomed to keep adding epicycles to failed models.

Well, if the neoclassical research agenda is borked, that means that the post-Keynesians aren’t, right? Not so fast. The post-Keynesians traded one set of dysfunctions for other ones — they are also trapped in the same publish-or-perish environment. Without mathematical models offering good quantitative predictions about the macroeconomy, it is hard to distinguish “good” literary analysis from “bad” analysis. They are not caught in the trap of generating epicycle papers, but the writing has evolved to be aimed at other post-Keynesians in order to get through the refereeing process. The texts are filled with so many digressions regarding who said what that trying to find a logical flow is difficult.

The MMT literature (that I am familiar with) was cleaner — because it took a '“back to first principles” approach, and focussed on some practical problems. The target audience was fairly explicitly non-MMTers. They were either responding to critiques (mainly post-Keynesians, since neoclassicals have a marked inability to deal with articles not published in their own journals), or outsiders interested in macro issues. It is very easy to predict when things go downhill — as soon as papers are published solely aimed at other MMT proponents.

Is there a way forward? My view is that there is — but nobody wants it to happen. Impossibility theorems could tell us what macroeconomic analysis cannot do. For example, when is it impossible to stabilise an economy with something like a Taylor Rule? In other words, my ideal graduate level macroeconomics theory textbook is a textbook explaining why you cannot do macroeconomic theory (as it is currently conceived).

Driving my German office mate crazy.

Uncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

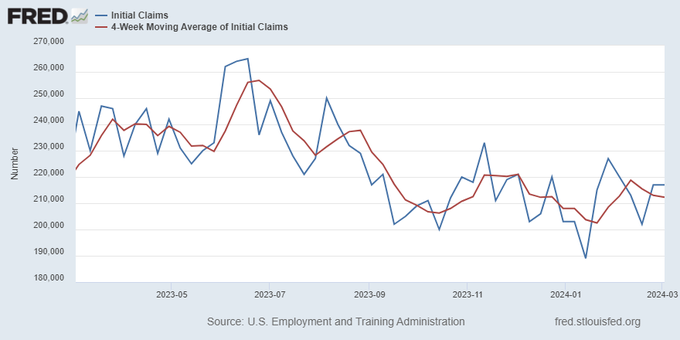

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

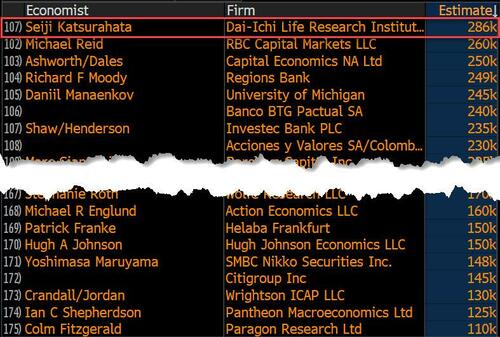

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

Uncategorized

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives…

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives floating around corporate media platforms has been the argument that the American people “just don’t seem to understand how good the economy really is right now.” If only they would look at the stats, they would realize that we are in the middle of a financial renaissance, right? It must be that people have been brainwashed by negative press from conservative sources…

I have to laugh at this notion because it’s a very common one throughout history – it’s an assertion made by almost every single political regime right before a major collapse. These people always say the same things, and when you study economics as long as I have you can’t help but throw up your hands and marvel at their dedication to the propaganda.

One example that comes to mind immediately is the delusional optimism of the “roaring” 1920s and the lead up to the Great Depression. At the time around 60% of the U.S. population was living in poverty conditions (according to the metrics of the decade) earning less than $2000 a year. However, in the years after WWI ravaged Europe, America’s economic power was considered unrivaled.

The 1920s was an era of mass production and rampant consumerism but it was all fueled by easy access to debt, a condition which had not really existed before in America. It was this illusion of prosperity created by the unchecked application of credit that eventually led to the massive stock market bubble and the crash of 1929. This implosion, along with the Federal Reserve’s policy of raising interest rates into economic weakness, created a black hole in the U.S. financial system for over a decade.

There are two primary tools that various failing regimes will often use to distort the true conditions of the economy: Debt and inflation. In the case of America today, we are experiencing BOTH problems simultaneously and this has made certain economic indicators appear healthy when they are, in fact, highly unstable. The average American knows this is the case because they see the effects everyday. They see the damage to their wallets, to their buying power, in the jobs market and in their quality of life. This is why public faith in the economy has been stuck in the dregs since 2021.

The establishment can flash out-of-context stats in people’s faces, but they can’t force the populace to see a recovery that simply does not exist. Let’s go through a short list of the most faulty indicators and the real reasons why the fiscal picture is not a rosy as the media would like us to believe…

The “miracle” labor market recovery

In the case of the U.S. labor market, we have a clear example of distortion through inflation. The $8 trillion+ dropped on the economy in the first 18 months of the pandemic response sent the system over the edge into stagflation land. Helicopter money has a habit of doing two things very well: Blowing up a bubble in stock markets and blowing up a bubble in retail. Hence, the massive rush by Americans to go out and buy, followed by the sudden labor shortage and the race to hire (mostly for low wage part-time jobs).

The problem with this “miracle” is that inflation leads to price explosions, which we have already experienced. The average American is spending around 30% more for goods, services and housing compared to what they were spending in 2020. This is what happens when you have too much money chasing too few goods and limited production.

The jobs market looks great on paper, but the majority of jobs generated in the past few years are jobs that returned after the covid lockdowns ended. The rest are jobs created through monetary stimulus and the artificial retail rush. Part time low wage service sector jobs are not going to keep the country rolling for very long in a stagflation environment. The question is, what happens now that the stimulus punch bowl has been removed?

Just as we witnessed in the 1920s, Americans have turned to debt to make up for higher prices and stagnant wages by maxing out their credit cards. With the central bank keeping interest rates high, the credit safety net will soon falter. This condition also goes for businesses; the same businesses that will jump headlong into mass layoffs when they realize the party is over. It happened during the Great Depression and it will happen again today.

Cracks in the foundation

We saw cracks in the narrative of the financial structure in 2023 with the banking crisis, and without the Federal Reserve backstop policy many more small and medium banks would have dropped dead. The weakness of U.S. banks is offset by the relative strength of the U.S. dollar, which lures in foreign investors hoping to protect their wealth using dollar denominated assets.

But something is amiss. Gold and bitcoin have rocketed higher along with economically sensitive assets and the dollar. This is the opposite of what’s supposed to happen. Gold and BTC are supposed to be hedges against a weak dollar and a weak economy, right? If global faith in the dollar and in the U.S. economy is so high, why are investors diving into protective assets like gold?

Again, as noted above, inflation distorts everything.

Tens of trillions of extra dollars printed by the Fed are floating around and it’s no surprise that much of that cash is flooding into the economy which simply pushes higher right along with prices on the shelf. But, gold and bitcoin are telling us a more honest story about what’s really happening.

Right now, the U.S. government is adding around $600 billion per month to the national debt as the Fed holds rates higher to fight inflation. This debt is going to crush America’s financial standing for global investors who will eventually ask HOW the U.S. is going to handle that growing millstone? As I predicted years ago, the Fed has created a perfect Catch-22 scenario in which the U.S. must either return to rampant inflation, or, face a debt crisis. In either case, U.S. dollar-denominated assets will lose their appeal and their prices will plummet.

“Healthy” GDP is a complete farce

GDP is the most common out-of-context stat used by governments to convince the citizenry that all is well. It is yet another stat that is entirely manipulated by inflation. It is also manipulated by the way in which modern governments define “economic activity.”

GDP is primarily driven by spending. Meaning, the higher inflation goes, the higher prices go, and the higher GDP climbs (to a point). Eventually prices go too high, credit cards tap out and spending ceases. But, for a short time inflation makes GDP (as well as retail sales) look good.

Another factor that creates a bubble is the fact that government spending is actually included in the calculation of GDP. That’s right, every dollar of your tax money that the government wastes helps the establishment by propping up GDP numbers. This is why government spending increases will never stop – It’s too valuable for them to spend as a way to make the economy appear healthier than it is.

The REAL economy is eclipsing the fake economy

The bottom line is that Americans used to be able to ignore the warning signs because their bank accounts were not being directly affected. This is over. Now, every person in the country is dealing with a massive decline in buying power and higher prices across the board on everything – from food and fuel to housing and financial assets alike. Even the wealthy are seeing a compression to their profit and many are struggling to keep their businesses in the black.

The unfortunate truth is that the elections of 2024 will probably be the turning point at which the whole edifice comes tumbling down. Even if the public votes for change, the system is already broken and cannot be repaired without a complete overhaul.

We have consistently avoided taking our medicine and our disease has gotten worse and worse.

People have lost faith in the economy because they have not faced this kind of uncertainty since the 1930s. Even the stagflation crisis of the 1970s will likely pale in comparison to what is about to happen. On the bright side, at least a large number of Americans are aware of the threat, as opposed to the 1920s when the vast majority of people were utterly conned by the government, the banks and the media into thinking all was well. Knowing is the first step to preparing.

The second step is securing your own financial future – that’s where physical precious metals can play a role. Diversifying your savings with inflation-resistant, uninflatable assets whose intrinsic value doesn’t rely on a counterparty’s promise to pay adds resilience to your savings. That’s the main reason physical gold and silver have been the safe haven store-of-value assets of choice for centuries (among both the elite and the everyday citizen).

* * *

As the world moves away from dollars and toward Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), is your 401(k) or IRA really safe? A smart and conservative move is to diversify into a physical gold IRA. That way your savings will be in something solid and enduring. Get your FREE info kit on Gold IRAs from Birch Gold Group. No strings attached, just peace of mind. Click here to secure your future today.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International17 hours ago

International17 hours agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges