Uncategorized

Zombie Welfare Functions

In a previous post, I challenged James Broughel’s recent suggestion that libertarians should re-evaluate their allegiance to the legacy of James Buchanan….

In a previous post, I challenged James Broughel’s recent suggestion that libertarians should re-evaluate their allegiance to the legacy of James Buchanan. There I focused on Broughel’s claims regarding Buchanan’s radical subjectivism. In this piece, I turn to the implications for welfare economics.

In his piece, Broughel wants to raise the zombie idea of social welfare functions, both in his critique of Buchanan and in an earlier Econlib piece. To see where these arguments go awry, it is helpful to review why mid-20th century economists were trying to construct plausible social welfare functions. Consider Figure 1.

Society faces tradeoffs in the production of various goods, such as guns and butter. (Buchanan would already hate this way of formulating the economic problem.) The concave curve is the set of possible efficient allocations of scarce productive resources. As long as society is somewhere on that curve, one cannot have more guns without giving up more butter or vice versa.[1] Suppose one buys, based on some modeling assumptions, that markets might get us in the neighborhood of the frontier. Some well-crafted policy interventions might be able to get us the rest of the way. That does not tell us where on the frontier we would like to go. The concept of economic efficiency cannot tell us whether it is better to be at point A, B, or C.

Economists sought after plausible social welfare functions to figure out where on the frontier to go. The point of a social welfare function is to rank possible states of the social world, even producing rankings among efficient states. This would allow economic science to say something about matters of distribution as well as efficiency without invoking interpersonal comparisons of utility. If markets could get us to efficiency and democracy to distributive justice, we would have a powerful defense of the liberal order.

Enter Kenneth Arrow. Arrow posits that a social welfare function should exhibit the same sort of rationality that economists typically posit of individual choosers. One feature of such rationality is transitivity: if A is preferred to B, and B to C, then A should be preferred to C. One way to get such rationality at the level of social orderings is to appoint a dictator. As long as the dictator is rational, the ranking of social states will be rational. For Arrow, this is an unattractive answer to the question that social welfare functions were meant to solve.

Arrow sought an aggregation procedure that would start from individual preferences and generate a set of rational social preferences. One constraint Arrow places on such a welfare function is the “independence of irrelevant alternatives” (IIA) which is meant to create the transitivity condition noted above. Majority rule cannot ensure this condition, because of what has long been called the Condorcet Paradox or Condorcet Cycle. If voters with the preference orderings in figure 2 confront pairwise choices, A defeats B and B defeats C, but C defeats A. There is no determinate will of the majority. If this is true for the trivial case of three voters and three options, it becomes even more likely as we increase the number of voters and the issues they might care about.

What is now called Arrow’s impossibility theorem shows that there is no collective decision procedure that satisfies the IIA alongside the other assumptions.

Back to Broughel. He argues that IIA is a bad assumption:

Broughel has attempted to engineer a situation in which a third “option” is in fact relevant. But getting into college is not a third option. It is a further consequence of the second option that would naturally inform the decision as to whether to party or not. There is of course no possibility of a paradox with only two options and one rational decision maker.

The next paragraph is even more problematic:

Arrow’s theorem does not entail that only immediate consequences should count in preference orderings. In fact, Arrow says the exact opposite. One of the other assumptions he makes is “universal domain:” all logically possible individual preference orderings are allowed.[2] This would include preferences for benefits that only manifest in the long term.

And Arrow’s theorem is in no way the foundation of modern cost-benefit analysis. Cost-benefit analysis concerns efficiency. Specifically, empirical cost-benefit analysis relies on the concept of Kaldor-Hicks efficiency since monetary outlays are measurable. Social welfare functions are mathematical constructs meant to rank Pareto efficient outcomes. Arrow spends an entire chapter of Social Choice and Individual Values arguing against the Kaldor-Hicks approach as a satisfactory social welfare function, so it is supremely odd to claim that his work is the basis of cost-benefit analysis.

Broughel’s next argumentative move is no better. He makes similar claims in his articles on Arrow and Buchanan.

Ironically, rejecting the use of any social welfare function at all, as some libertarians do, also implies rejecting the market process—which itself is guided by a social welfare function of sorts. Arrow himself acknowledges as much in his book that presents the impossibility theorem, Social Choice and Individual Values, when he concludes that “the market mechanism does not create a rational social choice.” Strangely, most libertarians have failed to heed the lesson.

Buchanan’s dismissal of the reasonableness of the social welfare function concept altogether likely contributed to many libertarians accepting Arrow’s theorem in a knee-jerk fashion. Yet, the market process itself operates under the guidance of a particular social welfare function (as Arrow understood, despite Buchanan arguing the opposite). Thus, libertarians who accept Buchanan and Arrow’s ideas inadvertently reject the process underlying the market, which forms the foundation of modern civilization.

Note the utterly strange claim that the market process is guided by a social welfare function. This is somewhat like saying that individual markets are guided by supply and demand diagrams. Not so. Supply and demand diagrams are a model of how markets work. But Broughel’s claim is even stranger than this because a social welfare function is a normative rather than positive construct. Its purpose is not predictive but evaluative. This comes across like a bizarre version of Hegelianism[3]: the social welfare function is realizing itself through the market process. That there is some funky metaphysics.

Perhaps Broughel means something different, though. Perhaps he means that markets must be judged by whether they produce rational social choices in accord with a social welfare function. This is the only way I can make sense of the claim that Arrow understood the importance of social welfare functions to the defense of markets. To which I respond: why?

Let me propose an alternative: social welfare functions were never that important to begin with. There is no reason to believe that the emergent properties of an economic or political system will conform to some set of rationalistic criteria derived from a model of individual decision making. Neither democracy nor markets aggregate preferences into a coherent ordering of social states. So what? This is, of course, Buchanan’s original point that Broughel links to. Arrow was simply wrong to claim that a system is justified to the extent that it approximates rationality.

For Broughel’s claim to be true, it must be the case that only a social welfare function is capable of underwriting normative support for markets (or democracy). But there are many alternative normative standards that could provide such support. Efficiency. Innovation. Discovery. Coordination. Natural rights. Basic rights. Public reason. Economic growth. Social morality. Virtue. Or mere agreement. One might be forgiven for believing that virtually any other normative standard is more useful than social welfare functions for judging economic and political institutions.

Description in Deficit

Broughel’s final beef with Buchanan concerns Buchanan’s view on deficits as burdening future generations.

Here Broughel echoes an argument initially made by Abba Lerner. Scarce resources cannot be literally borrowed from the future. The “social cost” of deficit financing is always paid today. Wealth is transferred from taxpayers to bond holders, but the scarce resources expended are the same whether public expenditure is financed through taxation or debt.[4]

Buchanan’s rejoinder is that future taxpayers do suffer a utility loss from having to transfer resources to bondholders. Regardless of the wisdom of the government spending, future taxpayers would be even better off if that spending had been financed with present taxation. In essence, Lerner is focused on the objective side of the ledger and Buchanan with the subjective side. Both insights are straightforward and difficult if not impossible to dispute.

Karen Vaughn and Richard Wagner reconcile Lange and Buchanan’s views on debt, along with Robert Barro’s concept of Ricardian Equivalence. The key insight of Barro’s view is likewise straightforward and uncontroversial: deficits are future taxes. Deficits thus reduce the present discounted value of assets held by individuals in the present.

Reconciling these three views requires recognizes that individuals are heterogeneous. Some have children, some do not. Some like their children more than others. There will thus be variation in intergenerational altruism. For those with lower levels of intergenerational altruism, deficit spending is a lower cost method for financing government expenditures. Deficit financing thus represents a transfer of wealth from those with high to those with low intergenerational altruism. It is a method of changing who pays for any given government expenditure. If some individuals who have political influence on the margin have less than complete intergenerational altruism, deficit financing also results in increasing the net amount of government spending.

Wagner has further developed this point in later work. Many decisions about fertility, marginal tax rates, and methods of servicing debt necessarily lie in the future. Deficit financing thus serves as a means of obscuring who ultimately bears the burden of government spending.

Broughel’s critique of Buchanan here is not based on an error but rather simply an incomplete picture. The only statement of his concerning deficits that I take substantive issue with is this:

Though he does not take it as far as others, this Lerneresque view is very close to that used by proponents of Modern Monetary Theory. Scarce resources used in government consumption or investment must come from somewhere. The ability to roll over debt does not make government spending into a magic goodies creator. We must keep in mind all three aspects of deficits—scarce resources, future utility losses, and Ricardian equivalence—in order to grasp the full consequences of deficit financing.

Concluding Thoughts

No thinker is above critique. There are many arguments in Buchanan that, in my view, simply do not work. But Broughel has failed to identify any substantive flaws in his thinking. Radical subjectivism does not obscure the losses imposed by government policies. Buchanan’s thoughts on debt do not imply that scarce resources can be shifted into the future. And social welfare functions should be left in the ground where Arrow and Buchanan buried them.

One final point of clarification: Buchanan’s work should not be judged by how useful it is for libertarianism. It should be judged on its own merits, whatever conclusions they point to. Paraphrasing Peter Boettke, libertarianism is a conversation for children. Liberal political economy is an adult conversation that freely engages with normative considerations, especially about the value of liberty. But it does not prejudge arguments as to whether they conclude that “state bad, market good.” Buchanan’s work is and will remain a vital and central contribution to that conversation.

[1] Alternatively, one could interpret this as a Pareto frontier, in which case it measures preference satisfaction for guns and butter. The same point applies.

[2] For those who hold out hope for social welfare functions, universal domain is actually the best point of attack.

[3] It goes without saying that all versions of Hegelianism are bizarre.

[4] There is a slight qualification in Lerner’s analysis: debt owed to parties external to the country can meaningfully be said to impose a burden. I set this aside to address more important considerations.

Adam Martin is Political Economy Research Fellow at the Free Market Institute and an assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics in the College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources at Texas Tech University.

For more articles by Adam Martin, see the Archive.

(0 COMMENTS) economic growthUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

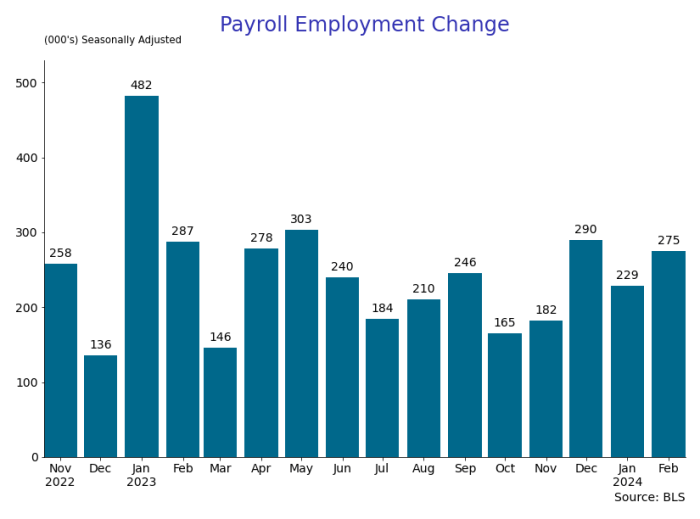

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

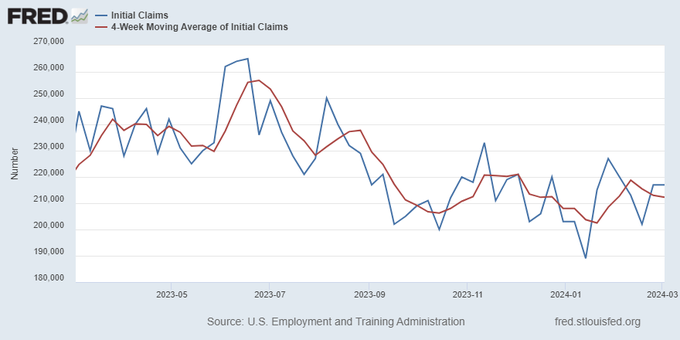

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire