Government

Why Goldman Expects The Most Flawless Fed Landing Ever: S&P 5,100 With GDP Double Consensus, Jobs, & Wage Growth … Yet 5 Rate Cuts As Inflation Tumbles

Why Goldman Expects The Most Flawless Fed Landing Ever: S&P 5,100 With GDP Double Consensus, Jobs, & Wage Growth … Yet 5 Rate Cuts As Inflation…

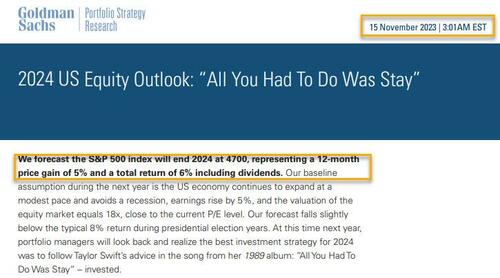

Back on November 15, when the S&P was trading at 4500, Goldman's chief equity strategist David Kostin triumphantly published his 2024 US equity outlook and S&P price target, one which was supposed to leave an indelible mark on clients' memories not least because it borrowed a line from that ultimate symbol of repeatedly chasing 15 minutes of fame, Taylor Swift, but because - well - it was supposed to be right, damn it and as a strategist you are paid to predict the future, something which for Kostin meant barely any increase in the S&P500, which he saw ending 2024 at 4,700, a paltry 5% increase from where it was in mid-November.

The problem is that as regular readers may recall, one year earlier, Kostin's similar attempts to predict the future crashed and burned spectacularly, as his 2023 year-ahead forecast - which was published in November 2022 when the S&P was trading at 4,000 - projected zero change for the S&P500 which Kostin expected would close the year unchanged at 4000 as the "cost of money is no longer next to nothing" (hence the far more subdued report title "Paradise Lost"). In retrospect, it turns out the cost of money had exactly zero impact on where stocks would close the year (indicatively, Kostin's year-ahead forecasts from 2021, 2020 and so on, were just as terrible).

It gets funnier: less than a month after Goldman - and every other bank - published their lengthy, 50+ page "2024 preview" pdf paperweights (which nobody besides us appears to read), Powell blew everyone up with his Dec 13 dovish pivot which ended any pretense that Powell was the second coming of Volcker (but was certainly a political emissary of the Biden White House at the Marriner Eccles building), and which instantly nuked every Wall Street sellside forecast. We said as much on Dec 14, when we lamented that "all those 2024 year-ahead Wall Street "forecasts" are now completely useless. Great job wasting weeks in the office for nothing."

Oh and all those 2024 year-ahead Wall Street "forecasts" are now completely useless. Great job wasting weeks in the office for nothing

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) December 15, 2023

Just a few hours later we were proven right again, when Kostin published a brand new forecast, making a mockery of his 2023 magnum opus (which, again, nobody had read), this time boldly hiking his 2024 price target from 4,700 to 5,100. Why? After all, besides Powell's dovish pivot, nothing else had changed in the preceding month (when the comprehensive 2024 full year forecast was published, a forecast which as the name implies is supposed to stay as is for, well, the full year). Well, with the S&P having already taken out his previous 2024 year-end target, Kostin had to come up with a bolder, more aggressive prediction (because never forget that on Wall Street all that matters is price, no matter how one gets to it), and he did just that, expecting the market to rise 8% (from 4,700) to 5,100, as "decelerating inflation and Fed easing will keep real yields low and support a P/E multiple greater than 19x."

Additionally, Kostin also explained that his prompt flip-flopping and "strong view of the equity market" also dovetailed with Goldman's "upgrades to the US GDP growth and interest rate outlooks. Following the Fed’s dovish signaling, our economists now expect the FOMC will cut the policy rate sooner and faster than they previously anticipated. Their revised funds rate forecast assumes consecutive 25 bp cuts in March, May, and June followed by quarterly cuts that will place the policy rate at 4.0%-4.25% at year-end 2024. Futures prices currently imply a total of six cuts to 3.75%-4.0% by the end of next year."

Which is amusing because while Goldman expects 5 rate cuts (vs the Fed's three and the market's six), Kostin writes that "equities were already pricing positive economic activity but now reflect an even more robust outlook. The performance of cyclical vs. defensive stocks has moved from pricing GDP growth of 1.5% to above 3% during the last seven weeks."

Which of course, is a paradox: why would the Fed be pivoting at all if the economy was not only not decelerating but was expected to grow at the fastest pace in over two years, leading to even lower unemployment and higher wages and price pressures. In other words, how could Goldman possibly justify 5 rate cuts while expecting the pace of economic growth to effectively double, yet at the same time, Goldman somehow sees core PCE inflation "on track for a striking slowdown from a 4% annualized pace in the first half of 2023 to a 2% pace in the second half... which strengthens our conviction that the rapid decline in US inflation is not just brief good luck—the “last mile” of the inflation fight is turning out not to be so hard after all."

These were some of the questions we were pondering after reading Kostin's revised price target (which we expect will be revised again as soon as the Fed realizes it has made another terrible policy mistake), and when Goldman's economist team published its final note for 2023, the customary "10 Questions for 2024" (full note available to pro subs in the usual place) we had high hopes that many of these paradoxical divergences would at least be at least superficially addressed if not explained. Alas, that was not the case, and we are now left with even more questions than before, which leads us to conclude that once again - like every year previously - either Goldman's cheerful market forecast or its even more cheerful economic outlook will be dead wrong. Most likely both.

So for the benefit of readers, who may be as confused as us and are left puzzled by what are increasingly more ridiculous mental acrobatics year after year to justify force-fed optimism by sellside strategists, we have excerpted some of the key rhetorical questions posed by Goldman in its full research note which discusses what Goldman believes "are the most important questions for 2024", a year when -as even the Fed found out the hard way - the US will hold what are perhaps the most important presidential elections in its history.

Below we excerpt from the Goldman Q&A (note here for pro subs). It's, as the name implies, a discussion Goldman's chief economist Jan Hatzius has with himself.

1. Will GDP grow faster than consensus and the FOMC expect?

Yes. We expect the US economy to substantially outperform expectations again in 2024. Our 2% forecast for 2024 Q4/Q4 GDP growth is more than double the Bloomberg consensus forecast of 0.9% and solidly above the FOMC’s forecast of 1.4% as well (Exhibit 1). But it is not a particularly bullish forecast in an absolute sense because we estimate that the economy’s short-run potential growth rate is currently about 2%, boosted modestly by above-trend immigration that is driving faster labor force growth.

A top-down explanation of why we expect GDP growth to be near potential next year is that the net effect of the impulses from changes in fiscal policy and changes in financial conditions is likely to be roughly neutral (Exhibit 2). This assessment is likely a key reason why we depart from consensus—many other forecasters still expect more lagged pain from higher interest rates than we do.

2. Will consumer spending beat consensus expectations?

Yes. Our forecast for consumer spending in 2024 is essentially a watered-down version of the 2023 story. We expect real disposable income to grow robustly again, though likely closer to 3% next year rather than this year’s 4%+ (Exhibit 4). Most of this comes from labor income gains—largely reflecting mundane potential growth in an economy with a growing labor force and rising productivity that tends to lift real wages—that should translate roughly one-for-one to higher consumer spending. The still-high level of job openings (Exhibit 8 below) implies that continued strong hiring is the default path and that expecting a virtuous cycle of income and consumption growth is not just circular reasoning.

Interest income will also likely rise meaningfully next year but should have a more modest per-dollar impact on spending because it accrues mostly to upper-income households. In part for this reason, we expect the saving rate to rise about 1pp, meaning that roughly 3% income growth should translate to roughly 2% consumption growth, well above consensus expectations of 1% growth.

More pessimistic forecasters highlight potential risks from more aggressive mean reversion of the saving rate from its low current level or from the exhaustion of excess savings. These concerns worry us less. The saving rate is low by historical standards at 4.1%, but it should be low because both precautionary and retirement motives for saving are currently weak. The layoff rate is historically low, and the ratio of household net worth to income is historically high. In that context, the low level of the saving rate is not that puzzling (Exhibit 5), though again our forecast does embed a modest increase next year.

Fears about the exhaustion of excess savings also look overblown. Pandemic savings likely provided key support for consumer spending in 2022, but because of two unusual circumstances that have not been true for a while—real income was falling, which meant that many families needed to tap their savings to sustain their real spending, and low-income households who usually do not have appreciable savings had some. Real income has instead risen in 2023 and the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances shows that the lowest-income families’ liquid financial assets had already fallen back to normal levels by the end of 2022. At this point, the remaining excess savings are a modest increment to the wealth of middle- and upper-income consumers that amount to about 1% of net worth and deserve less attention than they receive.

3. Will the gap between real goods and services consumption narrow back to the pre-pandemic trend?

No. Remote work appears likely to be the most persistent economic legacy of the pandemic. The share of US workers working from home at least part of the week has stabilized at around 20-25%, below its peak of 47% at the start of the pandemic but well above the pre-pandemic average of 2-3% (Exhibit 6).

This shift to working from home is likely the key driver of the large gap between goods and services consumption that has persisted even as virus fears have diminished. Real goods consumption was already growing more quickly in the pre-pandemic years and is now about 7% above trend, while real services consumption is still about 1% below trend (Exhibit 7). Metro-level credit card data show that remote workers spend less on office-adjacent services such as transportation and more on home office and recreation goods. This suggests that much of the shift in consumption patterns is likely to last.

4. Will bank lending reaccelerate?

Yes. The regional bank stress this spring provided the biggest growth scare of the year. Banks have reported a significant tightening in lending standards, and bank lending growth has slowed from 8% last year to just 2% this year. Some analysts worry that banks will face further pain from losses on commercial real estate (CRE) lending that could lead to a credit crunch next year.

We are less concerned and instead see room for bank lending to pick up. Our bank and credit analysts emphasize that much of the risk from CRE has already been priced into public debt markets and that banks’ limited exposure to office real estate should be manageable. And reassuringly, the most severe risks from the spring have been avoided—deposit outflows have remained modest, deposit betas remain within the range seen in past cycles, and net interest margins have held up. Now that interest rates are falling, the fears about unrealized losses on bank balance sheets that drove the initial panic should diminish further. Coupled with a brighter economic outlook for 2024 than the recession fears that dominated 2023, this should cause bank lending to pick back up.

Nonbank lenders cut back on new loans to businesses by less than banks this year, softening the impact on total credit availability, and should also be emboldened to lend more as recession fears fade.

5. Will the unemployment rate remain below 4%?

Yes. After a brief scare this fall, the unemployment rate ticked down to 3.7% in November. We have downplayed the modest uptick since the spring because other labor market data remain very strong: job openings remain high in aggregate and across nearly every industry (Exhibit 8, left), and layoffs and initial jobless claims remain very low (Exhibit 8, right).

This healthy starting point coupled with solid final demand growth and reduced recession fears should continue to support steady job gains in 2024 at a rate that only gradually converges later in the year to the breakeven pace, which we put at around 100k for now to incorporate an extra boost from elevated immigration. This should keep the unemployment rate fairly stable at around 3.6% (Exhibit 9).

6. Will wage growth fall below 4%?

Yes. The two main contributors to high wage growth over the last two years were a historically tight labor market in which our jobs-workers gap peaked at nearly 6 million, and large inflation shocks that raised near-term inflation expectations and sparked demands for much larger than usual cost-of-living adjustments. Both are now largely behind us. Measures of labor market tightness have returned to pre-pandemic levels, on average (Exhibit 10, left), and near-term inflation expectations have returned to levels that were consistent with 2% inflation in the years before the pandemic (Exhibit 10, right).

As a result, we expect wage growth to continue to fall with a bit of a lag. Our wage growth tracker has already slowed from a 5.5-6% peak pace to 4-4.5%, and business surveys that ask companies about their expectations for wage increases over the next year point to further deceleration to roughly the 3.5% rate that we estimate would be compatible with 2% inflation. Wage growth is the one piece of the broad inflation data set that is not yet quite where Fed officials would ideally like it to be before they start lowering interest rates. But it is close, and we suspect it remains elevated mainly because of the usual lags, which have been particularly visible in recent wage negotiations by union members, whose longer contracts have delayed the opportunity for some to win catch-up raises until this year.

7. Will core PCE inflation undershoot the FOMC’s forecast of 2.4% Q4/Q4?

Yes. Core PCE inflation has surprised to the downside recently and is on track for a striking slowdown from a 4% annualized pace in the first half of 2023 to a 2% pace in the second half. Our inflation forecast has fallen meaningfully as we have incorporated the good news (Exhibit 12). Similar patterns have also played out globally, which strengthens our conviction that the rapid decline in US inflation is not just brief good luck—the “last mile” of the inflation fight is turning out not to be so hard after all.

We are confident that year-on-year core PCE inflation will fall substantially next year from its current 3.2% rate because there is plenty of disinflation still in the pipeline from rebalancing in the labor, auto, and housing rental markets. With the auto strikes now over, inventory levels should continue to rebound quickly, which should further increase competition and reduce prices (Exhibit 13, left). We expect shelter inflation to remain firmer than some forecasters at 3.8% next year because while market rents have grown just 1-2% this year (Exhibit 13, right), we estimate that continuing-tenant rents still have to close a roughly 2% gap with market rates. But even this would be a big drop in a large category.

We expect core PCE inflation to fall 1pp from 3.2% to 2.2% by December 2024, reflecting a 1.1pp decline in core goods inflation to -1% and a 0.9pp decline in core services inflation to 3.4% (Exhibit 14).

8. Will the Fed cut at least four times?

Yes. Because inflation is returning to target surprisingly quickly and by some measures is already trending near 2%, we expect the FOMC to cut early and fast to reset the policy rate from a level that most of the FOMC will likely soon see as far offside. We expect three consecutive 25bp cuts in March, May, and June, followed by one cut per quarter (or every other meeting) until the funds rate reaches a terminal rate of 3.25-3.5% in 2025Q3. Our forecast implies 5 cuts in 2024 and 3 more cuts in 2025.

Our financial conditions index growth impulse model implies that the hit from higher rates is already behind us and that rate cuts are therefore optional next year, whereas Chair Powell said in December that the FOMC is “very focused” on the risk of staying too high for too long. We are also skeptical the neutral funds rate is as low as the FOMC thinks. But we are forecasting what the FOMC is likely to do, not what they “should” do, and its perspective on these issues implies that large cuts are more clearly urgent and appropriate than our analysis suggests (ZH: one wonders why what the Fed is likely to do and what it should do are so divergent... and then we remember: 2024 is an election year of course).

9. Will the Fed stop balance sheet reduction by Q3?

No. The FOMC will aim to stop balance sheet normalization when bank reserves go from “abundant” to “ample”—that is, when changes in the supply of reserves have a real but modest effect on short-term interest rates. We recently summarized a variety of indicators that can serve as warning signs that this point is approaching, and they still suggest that the end of runoff is a way off.

We expect the FOMC to start considering changes to the speed of runoff in 2024Q3, to slow the pace in 2024Q4, and to stop runoff in 2025Q1. At that point, we expect bank reserves to be around 12-13% of bank assets and the Fed’s balance sheet to be around 22% of GDP, versus 18% in 2019, a peak of almost 36%, and 28% currently. The main risk is that the increased supply of debt that we expect in 2024 could cause intermediation bottlenecks in the Treasury market that could lead the Fed to stop runoff earlier.

10. Will fiscal policy become more stimulative ahead of the election?

No. While fiscal policy has become somewhat more expansionary in presidential election years, on average, we do not expect this to be the case in 2024. This pattern is driven in part by the fiscal response to major downturns in some recent election years (e.g. 2008 and 2020) and we do not expect any substantial fiscal policy measures to be enacted in 2024.

Instead, we see some downside risk to government spending from automatic spending cuts that will take effect in May if Congress continues to avoid government shutdowns by passing temporary extensions instead of full-year spending bills. This is a serious risk because there is still a $120bn gap between House Republicans and the Senate on proposed spending levels. If the automatic cuts do take effect, they would cause a 1% cut to “discretionary” funding (0.2% of GDP) and, within that lower total, a reallocation of $33bn from defense to non-defense. Since this cut would be implemented in May 2024, it would be concentrated in the second half of the fiscal year, resulting in a step-down in funding of around 2% (0.4% of GDP).

To summarize: forget about a soft landing; Goldman is expecting the most flawless Fed landing in history, one where economic growth does not slow, but actually accelerates, one where a looming government shutdown does not serve as a headwind to growth, one where jobs and wages continue to post solid growth, yet one where inflation somehow drops as low as 2% despite a budget deficit that will be double that in 2023 and the Treasury will have to sell trillions more in debt. And the cherry on top: the S&P closes about 6% higher from today, printing at a record 5,100 on Dec 31. 2024 despite the Fed's reverse repo facility getting drained some time in March and despite QT then proceeding to cause havoc with the financial system and as it drains $100BN in liquidity every month. Good luck with that.

Much more in the full note available in the usual place.

International

Congress’ failure so far to deliver on promise of tens of billions in new research spending threatens America’s long-term economic competitiveness

A deal that avoided a shutdown also slashed spending for the National Science Foundation, putting it billions below a congressional target intended to…

Federal spending on fundamental scientific research is pivotal to America’s long-term economic competitiveness and growth. But less than two years after agreeing the U.S. needed to invest tens of billions of dollars more in basic research than it had been, Congress is already seriously scaling back its plans.

A package of funding bills recently passed by Congress and signed by President Joe Biden on March 9, 2024, cuts the current fiscal year budget for the National Science Foundation, America’s premier basic science research agency, by over 8% relative to last year. That puts the NSF’s current allocation US$6.6 billion below targets Congress set in 2022.

And the president’s budget blueprint for the next fiscal year, released on March 11, doesn’t look much better. Even assuming his request for the NSF is fully funded, it would still, based on my calculations, leave the agency a total of $15 billion behind the plan Congress laid out to help the U.S. keep up with countries such as China that are rapidly increasing their science budgets.

I am a sociologist who studies how research universities contribute to the public good. I’m also the executive director of the Institute for Research on Innovation and Science, a national university consortium whose members share data that helps us understand, explain and work to amplify those benefits.

Our data shows how underfunding basic research, especially in high-priority areas, poses a real threat to the United States’ role as a leader in critical technology areas, forestalls innovation and makes it harder to recruit the skilled workers that high-tech companies need to succeed.

A promised investment

Less than two years ago, in August 2022, university researchers like me had reason to celebrate.

Congress had just passed the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act. The science part of the law promised one of the biggest federal investments in the National Science Foundation in its 74-year history.

The CHIPS act authorized US$81 billion for the agency, promised to double its budget by 2027 and directed it to “address societal, national, and geostrategic challenges for the benefit of all Americans” by investing in research.

But there was one very big snag. The money still has to be appropriated by Congress every year. Lawmakers haven’t been good at doing that recently. As lawmakers struggle to keep the lights on, fundamental research is quickly becoming a casualty of political dysfunction.

Research’s critical impact

That’s bad because fundamental research matters in more ways than you might expect.

For instance, the basic discoveries that made the COVID-19 vaccine possible stretch back to the early 1960s. Such research investments contribute to the health, wealth and well-being of society, support jobs and regional economies and are vital to the U.S. economy and national security.

Lagging research investment will hurt U.S. leadership in critical technologies such as artificial intelligence, advanced communications, clean energy and biotechnology. Less support means less new research work gets done, fewer new researchers are trained and important new discoveries are made elsewhere.

But disrupting federal research funding also directly affects people’s jobs, lives and the economy.

Businesses nationwide thrive by selling the goods and services – everything from pipettes and biological specimens to notebooks and plane tickets – that are necessary for research. Those vendors include high-tech startups, manufacturers, contractors and even Main Street businesses like your local hardware store. They employ your neighbors and friends and contribute to the economic health of your hometown and the nation.

Nearly a third of the $10 billion in federal research funds that 26 of the universities in our consortium used in 2022 directly supported U.S. employers, including:

A Detroit welding shop that sells gases many labs use in experiments funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Department of Defense and Department of Energy.

A Dallas-based construction company that is building an advanced vaccine and drug development facility paid for by the Department of Health and Human Services.

More than a dozen Utah businesses, including surveyors, engineers and construction and trucking companies, working on a Department of Energy project to develop breakthroughs in geothermal energy.

When Congress shortchanges basic research, it also damages businesses like these and people you might not usually associate with academic science and engineering. Construction and manufacturing companies earn more than $2 billion each year from federally funded research done by our consortium’s members.

Jobs and innovation

Disrupting or decreasing research funding also slows the flow of STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – talent from universities to American businesses. Highly trained people are essential to corporate innovation and to U.S. leadership in key fields, such as AI, where companies depend on hiring to secure research expertise.

In 2022, federal research grants paid wages for about 122,500 people at universities that shared data with my institute. More than half of them were students or trainees. Our data shows that they go on to many types of jobs but are particularly important for leading tech companies such as Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Intel.

That same data lets me estimate that over 300,000 people who worked at U.S. universities in 2022 were paid by federal research funds. Threats to federal research investments put academic jobs at risk. They also hurt private sector innovation because even the most successful companies need to hire people with expert research skills. Most people learn those skills by working on university research projects, and most of those projects are federally funded.

High stakes

If Congress doesn’t move to fund fundamental science research to meet CHIPS and Science Act targets – and make up for the $11.6 billion it’s already behind schedule – the long-term consequences for American competitiveness could be serious.

Over time, companies would see fewer skilled job candidates, and academic and corporate researchers would produce fewer discoveries. Fewer high-tech startups would mean slower economic growth. America would become less competitive in the age of AI. This would turn one of the fears that led lawmakers to pass the CHIPS and Science Act into a reality.

Ultimately, it’s up to lawmakers to decide whether to fulfill their promise to invest more in the research that supports jobs across the economy and in American innovation, competitiveness and economic growth. So far, that promise is looking pretty fragile.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 16, 2024.

Jason Owen-Smith receives research support from the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Wellcome Leap.

economic growth covid-19 grants congress vaccine chinaInternational

What’s Driving Industrial Development in the Southwest U.S.

The post-COVID-19 pandemic pipeline, supply imbalances, investment and construction challenges: these are just a few of the topics address by a powerhouse…

The post-COVID-19 pandemic pipeline, supply imbalances, investment and construction challenges: these are just a few of the topics address by a powerhouse panel of executives in industrial real estate this week at NAIOP’s I.CON West in Long Beach, California. Led by Dawn McCombs, principal and Denver lead industrial specialist for Avison Young, the panel tackled some of the biggest issues facing the sector in the Western U.S.

Starting with the pandemic in 2020 and continuing through 2022, McCombs said, the industrial sector experienced a huge surge in demand, resulting in historic vacancies, rent growth and record deliveries. Operating fundamentals began to normalize in 2023 and construction starts declined, certainly impacting vacancy and absorption moving forward.

“Development starts dropped by 65% year-over-year across the U.S. last year. In Q4, we were down 25% from pre-COVID norms,” began Megan Creecy-Herman, president, U.S. West Region, Prologis, noting that all of that is setting us up to see an improvement of fundamentals in the market. “U.S. vacancy ended 2023 at about 5%, which is very healthy.”

Vacancies are expected to grow in Q1 and Q2, peaking mid-year at around 7%. Creecy-Herman expects to see an increase in absorption as customers begin to have confidence in the economy, and everyone gets some certainty on what the Fed does with interest rates.

“It’s an interesting dynamic to see such a great increase in rents, which have almost doubled in some markets,” said Reon Roski, CEO, Majestic Realty Co. “It’s healthy to see a slowing down… before [rents] go back up.”

Pre-pandemic, a lot of markets were used to 4-5% vacancy, said Brooke Birtcher Gustafson, fifth-generation president of Birtcher Development. “Everyone was a little tepid about where things are headed with a mediocre outlook for 2024, but much of this is normalizing in the Southwest markets.”

McCombs asked the panel where their companies found themselves in the construction pipeline when the Fed raised rates in 2022.

In Salt Lake City, said Angela Eldredge, chief operations officer at Price Real Estate, there is a typical 12-18-month lead time on construction materials. “As rates started to rise in 2022, lots of permits had already been pulled and construction starts were beginning, so those project deliveries were in fall 2023. [The slowdown] was good for our market because it kept rates high, vacancies lower and helped normalize the market to a healthy pace.”

A supply imbalance can stress any market, and Gustafson joked that the current imbalance reminded her of a favorite quote from the movie Super Troopers: “Desperation is a stinky cologne.” “We’re all still a little crazed where this imbalance has put us, but for the patient investor and owner, there will be a rebalancing and opportunity for the good quality real estate to pass the sniff test,” she said.

At Bircher, Gustafson said that mid-pandemic, there were predictions that one billion square feet of new product would be required to meet tenant demand, e-commerce growth and safety stock. That transition opened a great opportunity for investors to run at the goal. “In California, the entitlement process is lengthy, around 24-36 months to get from the start of an acquisition to the completion of a building,” she said. Fast forward to 2023-2024, a lot of what is being delivered in 2024 is the result of that chase.

“Being an optimistic developer, there is good news. The supply imbalance helped normalize what was an unsustainable surge in rents and land values,” she said. “It allowed corporate heads of real estate to proactively evaluate growth opportunities, opened the door for contrarian investors to land bank as values drop, and provided tenants with options as there is more product. Investment goals and strategies have shifted, and that’s created opportunity for buyers.”

“Developers only know how to run and develop as much as we can,” said Roski. “There are certain times in cycles that we are forced to slow down, which is a good thing. In the last few years, Majestic has delivered 12-14 million square feet, and this year we are developing 6-8 million square feet. It’s all part of the cycle.”

Creecy-Herman noted that compared to the other asset classes and opportunities out there, including office and multifamily, industrial remains much more attractive for investment. “That was absolutely one of the things that underpinned the amount of investment we saw in a relatively short time period,” she said.

Market rent growth across Los Angeles, Inland Empire and Orange County moved up more than 100% in a 24-month period. That created opportunities for landlords to flexible as they’re filling up their buildings. “Normalizing can be uncomfortable especially after that kind of historic high, but at the same time it’s setting us up for strong years ahead,” she said.

Issues that owners and landlords are facing with not as much movement in the market is driving a change in strategy, noted Gustafson. “Comps are all over the place,” she said. “You have to dive deep into every single deal that is done to understand it and how investment strategies are changing.”

Tenants experienced a variety of challenges in the pandemic years, from supply chain to labor shortages on the negative side, to increased demand for products on the positive, McCombs noted.

“Prologis has about 6,700 customers around the world, from small to large, and the universal lesson [from the pandemic] is taking a more conservative posture on inventories,” Creecy-Herman said. “Customers are beefing up inventories, and that conservatism in the supply chain is a lesson learned that’s going to stick with us for a long time.” She noted that the company has plenty of clients who want to take more space but are waiting on more certainty from the broader economy.

“E-commerce grew by 8% last year, and we think that’s going to accelerate to 10% this year. This is still less than 25% of all retail sales, so the acceleration we’re going to see in e-commerce… is going to drive the business forward for a long time,” she said.

Roski noted that customers continually re-evaluate their warehouse locations, expanding during the pandemic and now consolidating but staying within one delivery day of vast consumer bases.

“This is a generational change,” said Creecy-Herman. “Millions of young consumers have one-day delivery as a baseline for their shopping experience. Think of what this means for our business long term to help our customers meet these expectations.”

McCombs asked the panelists what kind of leasing activity they are experiencing as a return to normalcy is expected in 2024.

“During the pandemic, shifts in the ports and supply chain created a build up along the Mexican border,” said Roski, noting border towns’ importance to increased manufacturing in Mexico. A shift of populations out of California and into Arizona, Nevada, Texas and Florida have resulted in an expansion of warehouses in those markets.

Eldridge said that Salt Lake City’s “sweet spot” is 100-200 million square feet, noting that the market is best described as a mid-box distribution hub that is close to California and Midwest markets. “Our location opens up the entire U.S. to our market, and it’s continuing to grow,” she said.

The recent supply chain and West Coast port clogs prompted significant investment in nearshoring and port improvements. “Ports are always changing,” said Roski, listing a looming strike at East Coast ports, challenges with pirates in the Suez Canal, and water issues in the Panama Canal. “Companies used to fix on one port and that’s where they’d bring in their imports, but now see they need to be [bring product] in a couple of places.”

“Laredo, [Texas,] is one of the largest ports in the U.S., and there’s no water. It’s trucks coming across the border. Companies have learned to be nimble and not focused on one area,” she said.

“All of the markets in the southwest are becoming more interconnected and interdependent than they were previously,” Creecy-Herman said. “In Southern California, there are 10 markets within 500 miles with over 25 million consumers who spend, on average, 10% more than typical U.S. consumers.” Combined with the port complex, those fundamentals aren’t changing. Creecy-Herman noted that it’s less of a California exodus than it is a complementary strategy where customers are taking space in other markets as they grow. In the last 10 years, she noted there has been significant maturation of markets such as Las Vegas and Phoenix. As they’ve become more diversified, customers want to have a presence there.

In the last decade, Gustafson said, the consumer base has shifted. Tenants continue to change strategies to adapt, such as hub-and-spoke approaches. From an investment perspective, she said that strategies change weekly in response to market dynamics that are unprecedented.

McCombs said that construction challenges and utility constraints have been compounded by increased demand for water and power.

“Those are big issues from the beginning when we’re deciding on whether to buy the dirt, and another decision during construction,” Roski said. “In some markets, we order transformers more than a year before they are needed. Otherwise, the time comes [to use them] and we can’t get them. It’s a new dynamic of how leases are structured because it’s something that’s out of our control.” She noted that it’s becoming a bigger issue with electrification of cars, trucks and real estate, and the U.S. power grid is not prepared to handle it.

Salt Lake City’s land constraints play a role in site selection, said Eldridge. “Land values of areas near water are skyrocketing.”

The panelists agreed that a favorable outlook is ahead for 2024, and today’s rebalancing will drive a healthy industry in the future as demand and rates return to normalized levels, creating opportunities for investors, developers and tenants.

This post is brought to you by JLL, the social media and conference blog sponsor of NAIOP’s I.CON West 2024. Learn more about JLL at www.us.jll.com or www.jll.ca.

fed pandemic covid-19 real estate interest rates mexicoGovernment

Buyouts can bring relief from medical debt, but they’re far from a cure

Local governments are increasingly buying – and forgiving – their residents’ medical debt.

One in 10 Americans carry medical debt, while 2 in 5 are underinsured and at risk of not being able to pay their medical bills.

This burden crushes millions of families under mounting bills and contributes to the widening gap between rich and poor.

Some relief has come with a wave of debt buyouts by county and city governments, charities and even fast-food restaurants that pay pennies on the dollar to clear enormous balances. But as a health policy and economics researcher who studies out-of-pocket medical expenses, I think these buyouts are only a partial solution.

A quick fix that works

Over the past 10 years, the nonprofit RIP Medical Debt has emerged as the leader in making buyouts happen, using crowdfunding campaigns, celebrity engagement, and partnerships in the private and public sectors. It connects charitable buyers with hospitals and debt collection companies to arrange the sale and erasure of large bundles of debt.

The buyouts focus on low-income households and those with extreme debt burdens. You can’t sign up to have debt wiped away; you just get notified if you’re one of the lucky ones included in a bundle that’s bought off. In 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reviewed this strategy and determined it didn’t violate anti-kickback statutes, which reassured hospitals and collectors that they wouldn’t get in legal trouble partnering with RIP Medical Debt.

Buying a bundle of debt saddling low-income families can be a bargain. Hospitals and collection agencies are typically willing to sell the debt for steep discounts, even pennies on the dollar. That’s a great return on investment for philanthropists looking to make a big social impact.

And it’s not just charities pitching in. Local governments across the country, from Cook County, Illinois, to New Orleans, have been directing sizable public funds toward this cause. New York City recently announced plans to buy off the medical debt for half a million residents, at a cost of US$18 million. That would be the largest public buyout on record, although Los Angeles County may trump New York if it carries out its proposal to spend $24 million to help 810,000 residents erase their debt.

Nationally, RIP Medical Debt has helped clear more than $10 billion in debt over the past decade. That’s a huge number, but a small fraction of the estimated $220 billion in medical debt out there. Ultimately, prevention would be better than cure.

Preventing medical debt is trickier

Medical debt has been a persistent problem over the past decade even after the reforms of the 2010 Affordable Care Act increased insurance coverage and made a dent in debt, especially in states that expanded Medicaid. A recent national survey by the Commonwealth Fund found that 43% of Americans lacked adequate insurance in 2022, which puts them at risk of taking on medical debt.

Unfortunately, it’s incredibly difficult to close coverage gaps in the patchwork American insurance system, which ties eligibility to employment, income, age, family size and location – all things that can change over time. But even in the absence of a total overhaul, there are several policy proposals that could keep the medical debt problem from getting worse.

Medicaid expansion has been shown to reduce uninsurance, underinsurance and medical debt. Unfortunately, insurance gaps are likely to get worse in the coming year, as states unwind their pandemic-era Medicaid rules, leaving millions without coverage. Bolstering Medicaid access in the 10 states that haven’t yet expanded the program could go a long way.

Once patients have a medical bill in hand that they can’t afford, it can be tricky to navigate financial aid and payment options. Some states, like Maryland and California, are ahead of the curve with policies that make it easier for patients to access aid and that rein in the use of liens, lawsuits and other aggressive collections tactics. More states could follow suit.

Another major factor driving underinsurance is rising out-of-pocket costs – like high deductibles – for those with private insurance. This is especially a concern for low-wage workers who live paycheck to paycheck. More than half of large employers believe their employees have concerns about their ability to afford medical care.

Lowering deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums could protect patients from accumulating debt, since it would lower the total amount they could incur in a given time period. But if the current system otherwise stayed the same, then premiums would have to rise to offset the reduction in out-of-pocket payments. Higher premiums would transfer costs across everyone in the insurance pool and make enrolling in insurance unreachable for some – which doesn’t solve the underinsurance problem.

Reducing out-of-pocket liability without inflating premiums would only be possible if the overall cost of health care drops. Fortunately, there’s room to reduce waste. Americans spend more on health care than people in other wealthy countries do, and arguably get less for their money. More than a quarter of health spending is on administrative costs, and the high prices Americans pay don’t necessarily translate into high-value care. That’s why some states like Massachusetts and California are experimenting with cost growth limits.

Momentum toward policy change

The growing number of city and county governments buying off medical debt signals that local leaders view medical debt as a problem worth solving. Congress has passed substantial price transparency laws and prohibited surprise medical billing in recent years. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is exploring rule changes for medical debt collections and reporting, and national credit bureaus have voluntarily removed some medical debt from credit reports to limit its impact on people’s approval for loans, leases and jobs.

These recent actions show that leaders at all levels of government want to end medical debt. I think that’s a good sign. After all, recognizing a problem is the first step toward meaningful change.

Erin Duffy receives funding from Arnold Ventures.

congress trump pandemic-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International5 days ago

International5 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International5 days ago

International5 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges