Uncategorized

Towards an Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Analogue For Allocation of Emergency Medical Resources

Towards an Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Analogue For Allocation of Emergency Medical Resources

[TOTM: The following is part of a blog series by TOTM guests and authors on the law, economics, and policy of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The entire series of posts is available here.

This post is authored by Geoffrey A. Manne, (President, ICLE; Distinguished Fellow, Northwestern University Center on Law, Business, and Economics).]

There has been much (admittedly important) discussion of the economic woes of mass quarantine to thwart the spread and “flatten the curve” of the virus and its health burdens — as well as some extremely interesting discussion of the long-term health woes of quarantine and the resulting economic downturn: see, e.g., previous work by Christopher Ruhm suggesting mortality rates may improve during economic downturns, and this thread on how that might play out differently in the current health crisis.

But there is perhaps insufficient attention being paid to the more immediate problem of medical resource scarcity to treat large, localized populations of acutely sick people — something that will remain a problem for some time in places like New York, no matter how successful we are at flattening the curve.

Yet the fact that we may have failed to prepare adequately for the current emergency does not mean that we can’t improve our ability to respond to the current emergency and build up our ability to respond to subsequent emergencies — both in terms of future, localized outbreaks of COVID-19, as well as for other medical emergencies more broadly.

In what follows I lay out the outlines of a proposal for an OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network) analogue for allocating emergency medical resources. In order to make the idea more concrete (and because no doubt there is a limit to the types of medical resources for which such a program would be useful or necessary), let’s call it the VPAN — Ventilator Procurement and Allocation Network.

As quickly as possible in order to address the current crisis — and definitely with enough speed to address the next crisis — we should develop a program to collect relevant data and enable deployment of medical resources where they are most needed, using such data, wherever possible, to enable deployment before shortages become the enormous problem they are today.

Data and information are important tools for mitigating emergencies

Hal’s post, especially in combination with Julian’s, offers a really useful suggestion for using modern information technology to help mitigate one of the biggest problems of the current crisis: The ability to return to economic activity (and a semblance of normalcy) as quickly as possible.

What I like most about his idea (and, again, Julian’s) is its incremental approach: We don’t have to wait until it’s safe for everyone to come outside in order for some people to do so. And, properly collected, assessed, and deployed, information is a key part of making that possible for more and more people every day.

Here I want to build on Hal’s idea to suggest another — perhaps even more immediately crucial — use of data to alleviate the COVID-19 crisis: The allocation of scarce medical resources.

In the current crisis, the “what” of this data is apparent: it is the testing data described by Julian in his post, and implemented in digital form by Hal in his. Thus, whereas Hal’s proposal contemplates using this data solely to allow proprietors (public transportation, restaurants, etc.) to admit entry to users, my proposal contemplates something more expansive: the provision of Hal’s test-verification vendors’ data to a centralized database in order to use it to assess current medical resource needs and to predict future needs.

The apparent ventilator availability crisis

As I have learned at great length from a friend whose spouse is an ICU doctor on the front lines, the current ventilator scarcity in New York City is worrisome (from a personal email, edited slightly for clarity):

When doctors talk about overwhelming a medical system, and talk about making life/death decisions, often they are talking about ventilators. A ventilator costs somewhere between $25K to $50K. Not cheap, but not crazy expensive. Most of the time these go unused, so hospitals have not stocked up on them, even in first-rate medical systems. Certainly not in the US, where equipment has to get used or the hospital does not get reimbursed for the purchase.

With a bad case of this virus you can put somebody — the sickest of the sickest — on one of those for three days and many of them don’t die. That frames a brutal capacity issue in a local area. And that is what has happened in Italy. They did not have enough ventilators in specific cities where the cases spiked. The mortality rates were much higher solely due to lack of these machines. Doctors had to choose who got on the machine and who did not. When you read these stories about a choice of life and death, that could be one reason for it.

Now the brutal part: This is what NYC might face soon. Faster than expected, by the way. Maybe they will ship patients to hospitals in other parts of NY state, and in NJ and CT. Maybe they can send them to the V.A. hospitals. Those are the options for how they hope to avoid this particular capacity issue. Maybe they will flatten the curve just enough with all the social distancing. Hard to know just now. But right now the doctors are pretty scared, and they are planning for the worst.

A recent PBS Report describes the current ventilator situation in the US:

A 2018 analysis from the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security estimated we have around 160,000 ventilators in the U.S. If the “worst-case scenario” were to come to pass in the U.S., “there might not be” enough ventilators, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN on March 15.

“If you don’t have enough ventilators, that means [obviously] that people who need it will not be able to get it,” Fauci said. He stressed that it was most important to mitigate the virus’ spread before it could overwhelm American health infrastructure.

Reports say that the American Hospital Association believes almost 1 million COVID-19 patients in the country will require a ventilator. Not every patient will require ventilation at the same time, but the numbers are still concerning. Dr. Daniel Horn, a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, warned in a March 22 editorial in The New York Times that “There simply will not be enough of these machines, especially in major cities.”

The recent report of 9,000 COVID-19-related deaths in Italy brings the ventilator scarcity crisis into stark relief: There is little doubt that a substantial number of these deaths stem from the unavailability of key medical resources, including, most importantly, ventilators.

Medical resource scarcity in the current crisis is a drastic problem. And without significant efforts to ameliorate it it is likely to get worse before it gets better.

Using data to allocate scarce resources: The basic outlines of a proposed “Ventilator Procurement and Allocation Network”

But that doesn’t mean that the scarce resources we do have can’t be better allocated. As the PBS story quoted above notes, there are some 160,000 ventilators in the US. While that may not be enough in the aggregate, it’s considerably more than are currently needed in, say, New York City — and a great number of them are surely not currently being used, nor likely immediately to need to be used.

The basic outline of the idea for redistributing these resources is fairly simple:

- First, register all of the US’s existing ventilators in a centralized database.

- Second (using a system like the one Hal describes), collect and update in real time the relevant test results, contact tracing, demographic, and other epidemiological data and input it into a database.

- Third, analyze this data using one or more compartmental models (or more targeted, virus-specific models) — (NB: I am the furthest thing from an epidemiologist, so I make no claims about how best to do this; the link above, e.g., is merely meant to be illustrative and not a recommendation) — to predict the demand for ventilators at various geographic levels, ranging from specific hospitals to counties or states. In much the same way, allocation of organs in the OPTN is based on a set of “allocation calculators” (which in turn are intended to implement the “Final Rule” adopted by HHS to govern transplant organ allocation decisions).

- Fourth, ask facilities in low-expected-demand areas to send their unused (or excess above the level required to address “normal” demand) ventilators to those in high-expected-demand areas, with the expectation that they will be consistently reallocated across all hospitals and emergency care facilities according to the agreed-upon criteria. Of course, the allocation “algorithm” would be more complicated than this (as is the HHS Final Rule for organ allocation). But in principle this would be the primary basis for allocation.

Not surprisingly, some guidelines for the allocation of ventilators in such emergencies already exist — like New York’s Ventilator Allocation Guidelines for triaging ventilators during an influenza pandemic. But such guidelines address the protocols for each facility to use in determining how to allocate its own scarce resources; they do not contemplate the ability to alleviate shortages in the first place by redistributing ventilators across facilities (or cities, states, etc.).

I believe that such a system — like the OPTN — could largely work on a voluntary basis. Of course, I’m quick to point out that the OPTN is a function of a massive involuntary and distortionary constraint: the illegality of organ sales. But I suspect that a crisis like the one we’re currently facing is enough to engender much the same sort of shortage (as if such a constraint were in place with respect to the use of ventilators), and thus that a similar system would be similarly useful. If not, of course, it’s possible that the government could, in emergency situations, actually commandeer privately-owned ventilators in order to effectuate the system. I leave for another day the consideration of the merits and defects of such a regime.

Of course, it need not rely on voluntary participation. There could be any number of feasible means of inducing hospitals that have unused ventilators to put their surpluses into the allocation network, presumably involving some sort of cash or other compensation. Or perhaps, if and when such a system were expanded to include other medical resources, it might involve moving donor hospitals up the queue for some other scarce resources they need that don’t face a current crisis. Surely there must be equipment that a New York City hospital has in relative surplus that a small town hospital covets.

But the key point is this: It doesn’t make sense to produce and purchase enough ventilators so that every hospital in the country can simultaneously address extremely rare peak demands. Doing so would be extraordinarily — and almost always needlessly — expensive. And emergency preparedness is never about ensuring that there are no shortages in the worst-case scenario; it’s about making a minimax calculation (as odious as those are) — i.e., minimizing the maximal cost/risk, not mitigating risk entirely. (For a literature review of emergency logistics in the context of large-scale disasters, see, e.g., here)

But nor does it make sense — as a policy matter — to allocate the new ventilators that will be produced in response to current demand solely on the basis of current demand. The epidemiological externalities of the current pandemic are substantial, and there is little reason to think that currently over-taxed emergency facilities — or even those preparing for their own expected demand — will make procurement decisions that reflect the optimal national (let alone global) allocation of such resources. A system like the one I outline here would effectively enable the conversion of private, constrained decisions to serve the broader demands required for optimal allocation of scarce resources in the face of epidemiological externalities.

Indeed — and importantly — such a program allows the government to supplement existing and future public and private procurement decisions to ensure an overall optimal level of supply (and, of course, government-owned ventilators — 10,000 of which already exist in the Strategic National Stockpile — would similarly be put into the registry and deployed using the same criteria). Meanwhile, it would allow private facilities to confront emergency scenarios like the current one with far more resources than it would ever make sense for any given facility to have on hand in normal times.

Some caveats

There are, as always, caveats. First, such a program relies on the continued, effective functioning of transportation networks. If any given emergency were to disrupt these — and surely some would — the program would not necessarily function as planned. Of course, some of this can be mitigated by caching emergency equipment in key locations, and, over the course of an emergency, regularly redistributing those caches to facilitate expected deployments as the relevant data comes in. But, to be sure, at the end of the day such a program depends on the ability to transport ventilators.

In addition, there will always be the risk that emergency needs swamp even the aggregate available resources simultaneously (as may yet occur during the current crisis). But at the limit there is nothing that can be done about such an eventuality: Short of having enough ventilators on hand so that every needy person in the country can use one essentially simultaneously, there will always be the possibility that some level of demand will outpace our resources. But even in such a situation — where allocation of resources is collectively guided by epidemiological (or, in the case of other emergencies, other relevant) criteria — the system will work to mitigate the likely overburdening of resources, and ensure that overall resource allocation is guided by medically relevant criteria, rather than merely the happenstance of geography, budget constraints, storage space, or the like.

Finally, no doubt a host of existing regulations make such a program difficult or impossible. Obviously, these should be rescinded. One set of policy concerns is worth noting: privacy concerns. There is an inherent conflict between strong data privacy, in which decisions about the sharing of information belong to each individual, and the data needs to combat an epidemic, in which each person’s privately optimal level of data sharing may result in a socially sub-optimal level of shared data. To the extent that HIPAA or other privacy regulations would stand in the way of a program like this, it seems singularly important to relax them. Much of the relevant data cannot be efficiently collected on an opt-in basis (as is easily done, by contrast, for the OPTN). Certainly appropriate safeguards should be put in place (particularly with respect to the ability of government agencies/law enforcement to access the data). But an individual’s idiosyncratic desire to constrain the sharing of personal data in this context seems manifestly less important than the benefits of, at the very least, a default rule that the relevant data be shared for these purposes.

Appropriate standards for emergency preparedness policy generally

Importantly, such a plan would have broader applicability beyond ventilators and the current crisis. And this is a key aspect of addressing the problem: avoiding a myopic focus on the current emergency in lieu of more clear-eyed emergency preparedness plan.

It’s important to be thinking not only about the current crisis but also about the next emergency. But it’s equally important not to let political point-scoring and a bias in favor of focusing on the seen over the unseen coopt any such efforts. A proper assessment entails the following considerations (surely among others) (and hat tip to Ron Cass for bringing to my attention most of the following insights):

- Arguably we are overweighting health and safety concerns with respect to COVID-19 compared to our assessments in other areas (such as ordinary flu (on which see this informative thread by Anup Malani), highway safety, heart & coronary artery diseases, etc.). That’s inevitable when one particular concern is currently so omnipresent and so disruptive. But it is important that we not let our preparations for future problems focus myopically on this cause, because the next crisis may be something entirely different.

- Nor is it reasonable to expect that we would ever have been (or be in the future) fully prepared for a global pandemic. It may not be an “unknown unknown,” but it is impossible to prepare for all possible contingencies, and simply not sensible to prepare fully for such rare and difficult-to-predict events.

- That said, we also shouldn’t be surprised that we’re seeing more frequent global pandemics (a function of broader globalization), and there’s little reason to think that we won’t continue to do so. It makes sense to be optimally prepared for such eventualities, and if this one has shown us anything, it’s that our ability to allocate medical resources that are made suddenly scarce by a widespread emergency is insufficient.

- But rather than overreact to such crises — which is difficult, given that overreaction typically aligns with the private incentives of key decision makers, the media, and many in the “chattering class” — we should take a broader, more public-focused view of our response. Moreover, political and bureaucratic incentives not only produce overreactions to visible crises, they also undermine the appropriate preparation for such crises in the future.

- Thus, we should create programs that identify and mobilize generically useful emergency equipment not likely to be made obsolete within a short period and likely to be needed whatever the source of the next emergency. In other words, we should continue to focus the bulk of our preparedness on things like quickly deployable ICU facilities, ventilators, and clean blood supplies — not, as we may be wrongly inclined to do given the salience of the current crisis, primarily on specially targeted drugs and test kits. Our predictive capacity for our future demand of more narrowly useful products is too poor to justify substantial investment.

- Given the relative likelihood of another pandemic, generic preparedness certainly includes the ability to inhibit overly fast spread of a disease that can clog critical health care facilities. This isn’t disease-specific (or, that is, while the specific rate and contours of infection are specific to each disease, relatively fast and widespread contagion is what causes any such disease to overtax our medical resources, so if we’re preparing for a future virus-related emergency, we’re necessarily preparing for a disease that spreads quickly and widely).

Because the next emergency isn’t necessarily going to be — and perhaps isn’t even likely to be — a pandemic, our preparedness should not be limited to pandemic preparedness. This means, as noted above, overcoming the political and other incentives to focus myopically on the current problem even when nominally preparing for the next one. But doing so is difficult, and requires considerable political will and leadership. It’s hard to conceive of our current federal leadership being up to the task, but it’s certainly not the case that our current problems are entirely the makings of this administration. All governments spend too much time and attention solving — and regulating — the most visible problems, whether doing so is socially optimal or not.

Thus, in addition to (1) providing for the efficient and effective use of data to allocate emergency medical resources (e.g., as described above), and (2) ensuring that our preparedness centers primarily on generically useful emergency equipment, our overall response should also (3) recognize and correct the way current regulatory regimes also overweight visible adverse health effects and inhibit competition and adaptation by industry and those utilizing health services, and (4) make sure that the economic and health consequences of emergency and regulatory programs (such as the current quarantine) are fully justified and optimized.

A proposal like the one I outline above would, I believe, be consistent with these considerations and enable more effective medical crisis response in general.

The post Towards an Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Analogue For Allocation of Emergency Medical Resources appeared first on Truth on the Market.

Uncategorized

February Employment Situation

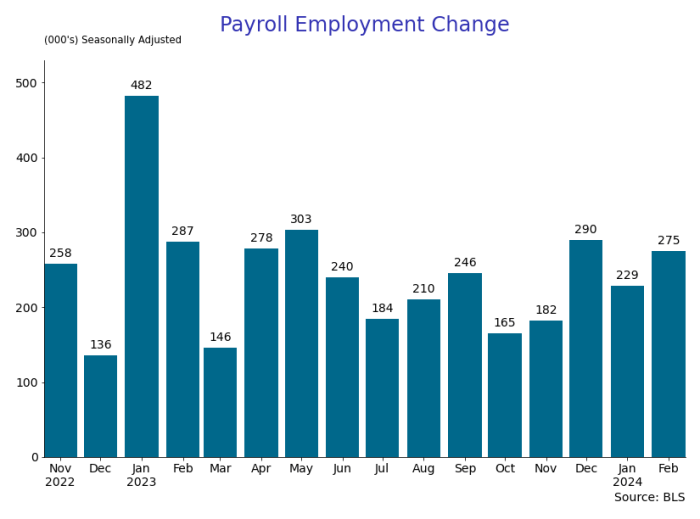

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

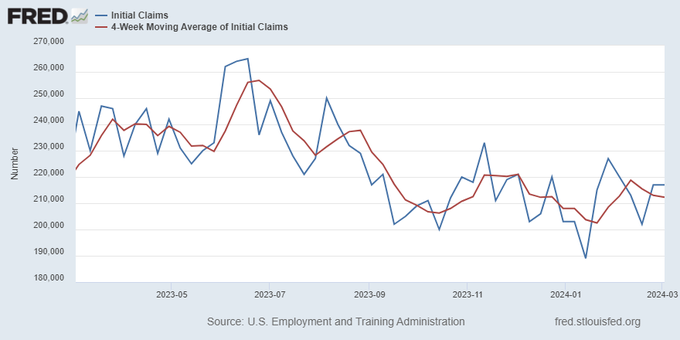

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

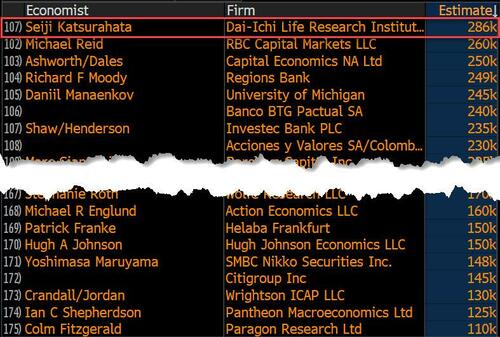

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges