Uncategorized

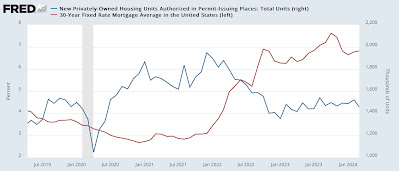

Simultaneous declines in housing permits, starts, and units under construction in March suggests seasonality glitch, not a change in trend

– by New Deal democratThere was a big decline in housing starts last month, and a smaller but significant decline in permits. Whether that signifies…

- by New Deal democrat

Uncategorized

Supreme Court to consider whether local governments can make it a crime to sleep outside if no inside space is available

Legal precedents hold that criminalizing someone for their status, such as being homeless, is cruel and unusual punishment. But what if that status leads…

On April 22, 2024, the Supreme Court will hear a case that could radically change how cities respond to the growing problem of homelessness. It also could significantly worsen the nation’s racial justice gap.

City of Grants Pass v. Johnson began when a small city in Oregon with just one homeless shelter began enforcing a local anti-camping law against people sleeping in public using a blanket or any other rudimentary protection against the elements – even if they had nowhere else to go. The court must now decide whether it is unconstitutional to punish homeless people for doing in public things that are necessary to survive, such as sleeping, when there is no option to do these acts in private.

The case raises important questions about the scope of the Constitution’s cruel and unusual punishment clause and the limits of cities’ power to punish involuntary conduct. As a specialist in poverty law, civil rights and access to justice who has litigated many cases in this area, I know that homelessness in the U.S. is a function of poverty, not criminality, and is strongly correlated with racial inequality. In my view, if cities get a green light to continue criminalizing inevitable behaviors, these disparities can only increase.

A national crisis

Homelessness in the United States is a massive problem. The number of people without homes held steady during the COVID-19 pandemic largely because of eviction moratoriums and the temporary availability of expanded public benefits, but it has risen sharply since 2022.

The latest data from the federal government’s annual “Point-in-Time” homeless count found 653,000 people homeless across the U.S. on a single night in 2023 – a 12% increase from 2022 and the highest number reported since the counts began in 2007. Of the people counted, nearly 300,000 were living on the street or in parks, rather than indoors in temporary shelters or safe havens.

The survey also shows that all homelessness is not the same. About 22% of homeless people are deemed chronically homeless, meaning they are without shelter for a year or more, while most experience a temporary or episodic lack of shelter. A 2021 study found that 53% of homeless shelter residents and nearly half of unsheltered people were employed.

Scholars and policymakers have spent many years analyzing the causes of homelessness. They include wage stagnation, shrinking public benefits, inadequate treatment for mental illness and addiction, and the politics of siting affordable housing. There is little disagreement, however, that the simple mismatch between the vast need for affordable housing and the limited supply is a central cause.

Homelessness and race

Like poverty, homelessness in the U.S. is not race-neutral. Black Americans represent 13% of the population but comprise 21% of people living in poverty and 37% of people experiencing homelessness.

The largest percentage increase in homelessness for any racial group in 2023 was 40% among Asians and Asian-Americans. The largest numerical increase was among people identifying as what the Department of Housing and Urban Development calls “Latin(a)(o)(x),” with nearly 40,000 more homeless in 2023 than in 2022.

This disproportionality means that criminalizing homelessness likewise has a disparate racial effect. A 2020 study in Austin, Texas, showed that Black homeless people were 10 times more likely than white homeless people to be cited by police for camping on public property.

According to a recent report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, 1 in 8 Atlanta city jail bookings in 2022 were of people experiencing homelessness. The criminalization of homelessness has roots in historical use of vagrancy and loitering laws against Black Americans dating back to the 19th century.

Crackdowns on the homeless

Increasing homelessness, especially its visible manifestations such as tent encampments, has frustrated city residents, businesses and policymakers across the U.S. and led to an increase in crackdowns against homeless people. Reports from the National Homelessness Law Center in 2019 and 2021 have tallied hundreds of laws restricting camping, sleeping, sitting, lying down, panhandling and loitering in public.

Just since 2022, Texas, Tennessee and Missouri have passed statewide bans on camping on public property, with Texas making it a felony.

Georgia has enacted a law requiring localities to enforce public camping bans. Even some cities led by Democrats, including San Diego and Portland, Oregon, have established tougher anti-camping regulations.

Under presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden, the federal government has asserted that criminal sanctions are rarely useful. Instead it has emphasized alternatives, such as supportive services, specialty courts and coordinated systems of care, along with increased housing supply.

Some cities have had striking success with these measures. But not all communities are on board.

The Grants Pass case

Grants Pass v. Johnson culminates years of struggle over how far cities can go to discourage homeless people from residing within their borders, and whether or when criminal sanctions for actions such as sleeping in public are permissible.

In a 2019 case, Martin v. City of Boise, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held that the Eighth Amendment’s cruel and unusual punishment clause forbids criminalizing sleeping in public when a person has no private place to sleep. The decision was based on a 1962 Supreme Court case, Robinson v. California, which held that it is unconstitutional to criminalize being a drug addict. Robinson and a subsequent case, Powell v. Texas, have come to stand for distinguishing between status, which cannot constitutionally be punished, and conduct, which can.

In the Grants Pass ruling, the 9th Circuit went one step further than it had in the Boise case and held that the Constitution also banned criminalizing the act of public sleeping with rudimentary protection from the elements. The decision was contentious: Judges disagreed over whether the anti-camping ban regulated conduct or the status of being homeless, which inevitably leads to sleeping outside when there is no alternative.

Grants Pass is urging the Supreme Court to abandon the Robinson precedent and its progeny as “moribund and misguided.” It argues that the Eighth Amendment forbids only certain cruel methods of punishment, which do not include fines and jail terms.

The homeless plaintiffs argue that they do not challenge reasonable regulation of the time and place of outdoor sleeping, the city’s ability to limit the size or location of homeless groups or encampments, or the legitimacy of punishing those who insist on remaining in public when shelter is available. But they argue that broad anti-camping laws inflict overly harsh punishments for “wholly innocent, universally unavoidable behavior” and that punishing people for “simply existing outside without access to shelter” will not reduce this activity.

They contend that criminalizing sleeping in public when there is no alternative violates the Eighth Amendment in three ways: by criminalizing the “status” of homelessness, by imposing disproportionate punishment on innocent and unavoidable acts, and by imposing punishment without a legitimate deterrent or rehabilitative goal.

The case has attracted dozens of amicus briefs, including from numerous cities and counties that support Grants Pass. They assert that the 9th Circuit’s recent decisions have worsened homelessness, stymied law enforcement and left jurisdictions without clear guidelines for preserving public order and safety.

On the other hand, the states of Maryland, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York and Vermont filed a brief urging the Court to uphold the 9th Circuit’s ruling, arguing that local governments retain ample tools to address homelessness and that criminalizing tends to worsen rather than alleviate the problem.

A brief from 165 former local elected officials agrees. Service providers, social scientists and professional organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association filed briefs noting that criminalization increases barriers to education, employment and eventual recovery; erodes community trust; and can force people back into abusive situations. They also highlight research showing the effectiveness of a nonpunitive “housing first” model.

A race to the bottom?

The current Supreme Court is generally extremely sympathetic to law enforcement, but even its conservative members may balk at allowing a city to criminalize inevitable acts by homeless people. Doing so could spark competition among cities to create the most punitive regime in hopes of effectively banishing homeless residents.

Still, at least some justices may sympathize with the city’s argument that upholding the 9th Circuit’s ruling “logically would immunize numerous other purportedly involuntary acts from prosecution, such as drug use by addicts, public intoxication by alcoholics, and possession of child pornography by pedophiles.” However the court rules, this case will likely affect the health and welfare of thousands of people experiencing homelessness in cities across the U.S.

Clare Pastore is a former Senior Counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, which is one of the ACLU offices included in the organization's amicus brief in the case supporting the homeless litigants in city of Grants Pass v. Johnson. Her employment with the ACLU ended in 2007, years before this case was filed.

grants pandemic covid-19 treatment recoveryUncategorized

Grizzly bear conservation is as much about human relationships as it is the animals

Whether people are hunters can have a big effect.

Montanans know spring has officially arrived when grizzly bears emerge from their dens. But unlike the bears, the contentious debate over their future never hibernates. New research from my lab reveals how people’s social identities and the dynamics between social groups may play a larger role in these debates than even the animals themselves.

Social scientists like me work to understand the human dimensions behind wildlife conservation and management. There’s a cliché among wildlife biologists that wildlife management is really people management, and they’re right. My research seeks to understand the psychological and social factors that underlie pressing environmental challenges. It is from this perspective that my team sought to understand how Montanans think about grizzly bears.

To list or delist, that is the question

In 1975, the grizzly bear was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act following decades of extermination efforts and habitat loss that severely constrained their range. At that time, there were 700-800 grizzly bears in the lower 48 states, down from a historic 50,000. Today, there are about 2,000 grizzly bears in this area, and sometime in 2024 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will decide whether to maintain their protected status or begin the delisting process.

Listed species are managed by the federal government until they have recovered and management responsibility can return to the states. While listed, federal law prevents hunting of the animal and destruction of grizzly bear habitat. If the animal is delisted, some states intend to implement a grizzly bear hunting season.

People on both sides of the delisting debate often use logic to try to convince others that their position is right. Proponents of delisting say that hunting grizzly bears can help reduce conflict between grizzly bears and humans. Opponents of delisting counter that state agencies cannot be trusted to responsibly manage grizzly bears.

But debates over wildlife might be more complex than these arguments imply.

Identity over facts

Humans have survived because of our evolved ability to cooperate. As a result, human brains are hardwired to favor people who are part of their social groups, even when those groups are randomly assigned and the group members are anonymous.

Humans perceive reality through the lens of their social identities. People are more likely to see a foul committed by a rival sports team than one committed by the team they’re rooting for. When randomly assigned to be part of a group, people will even overlook subconscious racial biases to favor their fellow group members.

Leaders can leverage social identities to inspire cooperation and collective action. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, people with strong national identities were more likely to physically distance and support public health policies.

But the forces of social identity have a dark side, too. For example, when people think that another “out-group” is threatening their group, they tend to assume members of the other group hold more extreme positions than they really do. Polarization between groups can worsen when people convince themselves that their group’s positions are inherently right and the other group’s are wrong. In extreme instances, group members can use these beliefs to justify immoral treatment of out-group members.

Empathy reserved for in-group members

These group dynamics help explain people’s attitudes toward grizzly bears in Montana. Although property damage from grizzly bears is extremely rare, affecting far less than 1% of Montanans each year, grizzly bears have been known to break into garages to access food, prey on free-range livestock and sometimes even maul or kill people.

People who hunt tend to have more negative experiences with grizzly bears than nonhunters – usually because hunters are more often living near and moving through grizzly bear habitat.

In a large survey of Montana residents, my team found that one of the most important factors associated with negative attitudes toward grizzly bears was whether someone had heard stories of grizzly bears causing other people property damage. We called this “vicarious property damage.” These negative feelings toward grizzly bears are highly correlated with the belief that there are too many grizzly bears in Montana already.

But we also found an interesting wrinkle in the data. Although hunters extended empathy to other hunters whose properties had been damaged by grizzly bears, nonhunters didn’t show the same courtesy. Because property damage from grizzly bears was far more likely to affect hunters, only other hunters were able to put themselves in their shoes. They felt as though other hunters’ experiences may as well have happened to them, and their attitudes toward grizzly bears were more negative as a result.

For nonhunters, hearing stories about grizzly bears causing damage to hunters’ property did not affect their attitudes toward the animals.

Identity-informed conservation

Recognizing that social identities can play a major role in wildlife conservation debates helps untangle and perhaps prevent some of the conflict. For those wishing to build consensus, there are many psychology-informed strategies for improving relationships between groups.

For example, conversations between members of different groups can help people realize they have shared values. Hearing about a member of your group helping a member of another group can inspire people to extend empathy to out-group members.

Conservation groups and wildlife managers should take care when developing interventions based on social identity to prevent them from backfiring when applied to wildlife conservation issues. Bringing up social identities can sometimes cause unintended division. For example, partisan politics can unnecessarily divide people on environmental issues.

Wildlife professionals can reach their audience more effectively by matching their message and messengers to the social identities of their audience. Some conservation groups have seen success uniting community members who might otherwise be divided around a shared identity associated with their love of a particular place. The conservation group Swan Valley Connections has used this strategy in Montana’s Swan Valley to reduce conflict between grizzly bears and local residents.

Group dynamics can foster cooperation or create division, and the debate over grizzly bear management in Montana is no exception. Who people are and who they care about drives their reactions to this large carnivore. Grizzly bear conservation efforts that unite people around shared identities are far more likely to succeed than those that remind them of their divisions.

Alexander L. Metcalf has received funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the Richard King Mellon Foundation, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, the US Geological Survey, and the US Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Dr. Metcalf is an advisor to the Swan Valley Connections board of directors.

treatment pandemic covid-19Uncategorized

Iconic ice cream brand files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy

The nearly 100-year-old ice cream retailer seeks to reorganize in Chapter 11.

Ice cream chain competition is fierce as Dunkin Brands' (DNKN) Baskin Robbins, Cold Stone Creamery, Haagen-Dazs, Marble Slab Creamery and Ben & Jerry's, dominate the space. Certain burger chains, such as Dairy Queen, Sonic and Culver's, also have long-established popularity with their ice cream offerings.

It's still difficult for burger chains to top the pure ice cream chains as huge Baskin Robbins had 2,376 locations in 2023, according to data firm ScrapeHero, Cold Stone Creamery had 998 locations in the U.S. as of Jan. 25, 2024, the data firm also revealed.

Related: Las Vegas Strip resort signs iconic hip hop stars for residency

General Mills' (GIS) Haagen-Dazs has over 900 locations in 50 countries, according to the company's parent and cereal maker's website, and Fat Brands (FAT) affiliate Marble Slab Creamery had over 395 locations in 22 states, according to the parent company website. Ben & Jerry's number of locations were unclear, but software company Rentech Digital claimed the company had over 200 locations in 2021, Eat This, Not That reported.

The ice cream business hasn't been too friendly to some companies. Friendly's restaurant chain, which specialized in its ice cream business, battled both restaurant and ice cream rivals before making its first trip to bankruptcy in 2011. The company was sold five years after that bankruptcy, but would face financial distress caused by the Covid pandemic and filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy a second time in November 2020.

Friendly's seeks Texas franchises

In January 2021, Amici Partners Group and its affiliate Brix Holdings acquired 130 corporate-owned and franchised Friendly's restaurants out of bankruptcy. Now, Brix Holdings is looking to expand as it said in a February 2024 statement that the company is looking for Texas entrepreneurs to open multiple locations to extend its franchise network outside of its Northeast market.

"Friendly's has the potential to be a beloved brand on a national scale in the way that it already is on the East Coast," Sherif Mityas, CEO of Brix Holdings LLC, said in a statement. "We know there are business owners out there, especially in states like Texas, who understand the legacy, impact and opportunities Friendly's will bring to new communities. For more than eight decades, the brand has continued to grow and evolve with today's culture. The company's longevity and resilience proves its opportunities are limitless and the concept can go far with the right entrepreneur."

While one former distressed ice cream brand may have recovered, another longtime regional ice cream brand has fallen into bankruptcy.

Oberweis Ice Cream and Dairy to reorganize in bankruptcy

The iconic operator of Oberweis Ice Cream and Dairy retail stores in the Midwest, which was founded in 1927, on April 12 filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy to reorganize its business.

Oberwies is a throwback to the heyday of dairies as it still sells its milk in glass bottles and offers home delivery of its dairy products in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, Virginia and Wisconsin.

The company, which opened its first ice cream shop in 1951, currently operates 43 Oberweis Ice Cream and Dairy retail locations in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Missouri.

The North Aurora, Ill.-based ice cream and dairy retailer listed $10 million to $50 million in assets and liabilities in its petition. The debtor listed about $4 million owed to its top 20 unsecured creditors that included Penske Truck Co. and food safety company EcoLab as well as over $173,000 to the Cook County Treasurer, Chicago NBC affiliate WMAQ reported.

bankruptcy pandemic-

International4 weeks ago

International4 weeks agoParexel CEO to retire; CAR-T maker AffyImmune promotes business leader to chief executive

-

Spread & Containment1 month ago

Spread & Containment1 month agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Government1 week ago

Government1 week agoClimate-Con & The Media-Censorship Complex – Part 1

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoWHO Official Admits Vaccine Passports May Have Been A Scam

-

Spread & Containment1 week ago

Spread & Containment1 week agoFDA Finally Takes Down Ivermectin Posts After Settlement

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoVaccinated People Show Long COVID-Like Symptoms With Detectable Spike Proteins: Preprint Study

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoCan language models read the genome? This one decoded mRNA to make better vaccines.

-

Uncategorized1 week ago

Uncategorized1 week agoWhat’s So Great About The Great Reset, Great Taking, Great Replacement, Great Deflation, & Next Great Depression?