International

Judy Shelton: Fed Can Only “Kill The Economy” With “Whatever It Takes” Approach

Judy Shelton: Fed Can Only "Kill The Economy" With "Whatever It Takes" Approach

Authored by Andrew Moran via The Epoch Times,

Jerome Powell…

Authored by Andrew Moran via The Epoch Times,

Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve have been on a crusade to navigate the U.S. economy to a soft landing rather than a hard crash as it struggles to fight 40-year high inflation while averting a recession.

Can the central bank achieve this ostensibly difficult objective?

If the central bank’s track record is anything to go by, the Fed is “not omniscient,” says Judy Shelton, a senior fellow at the Independent Institute and former Federal Reserve board nominee, in a wide-ranging interview with The Epoch Times.

According to Shelton, it will be challenging to prognosticate the lasting effects of pushing up the benchmark Fed funds rate to a neutral level after exerting tremendous influence on the economy for the last two years.

“I think it’s also hard to say what will be the impact and what will be the timing of the impact of ratcheting up interest rates to the point where they choke off real economic activity,” she said. “There’s a big difference in saying money that comes from speculating on money that can generate income, versus GDP growth that reflects an increase in the level of goods and services available.”

Jerome Powell departs after taking the oath of office for his second term as Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System at the Federal Reserve Building in Washington, on May 23, 2022. (Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images)

A key hurdle that the Fed will need to overcome is having the real interest rate higher than the inflation rate, notes Shelton. In addition, the neutral rate—a rate that neither supports nor restricts economic growth—would need to run higher than what officials forecast price measurements will be at the end of the year, be it the consumer price index (CPI) or the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index.

“If the Fed is looking at pushing up the Fed funds rate to 2.4 or 2.5 percent, but inflation is running anything higher than let’s say 1 percent, then you’re still effectively having interest rates serving as a stimulus in the Keynesian sense,” she explained.

“The Fed would have to get in front of that. I don’t think they would do that.”

But the institution’s “whatever it takes” approach to combating inflation “is not an admirable solution,” according to the former U.S. executive director for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Powell acknowledged last month at a post-FOMC press conference that when the Fed reaches its neutral rate roughly at the end of the year, the Fed could tighten policy even further “if that turns out to be appropriate.” This would make borrowing costlier, but it would also restrain economic growth.

Financial markets are pricing in a benchmark rate as high as 3.6 percent by the middle of next year, although St. Louis Fed Bank President James Bullard has repeatedly purported that he wants to get to 3.5 percent by the year’s end. If the Fed does accelerate its rate hikes, this would be the highest interest rate in about 15 years.

The rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will be holding its next two-day policy meeting later this month. It is widely expected that officials will vote to approve a 50-basis-point hike.

In addition to consumers losing more than 8 percent a year in purchasing power, higher interest rates will also cause financial strain on many households that took on greater debt levels, asserts Shelton.

This is why she believes it has become a mistake to allow a small group of people to determine what the price of capital should be, suggesting that it might be time to adopt a more market-oriented approach to interest rates.

“I think we need to bring market forces into determining the price of capital, which is the interest rate on the basis of supply and demand, and have a more organic approach to calibrating the level of cash and credit to the needs of a productive economy,” Shelton said.

Fundamental Monetary Reforms

Overall, Shelton does not think the Federal Reserve has done a good job since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. But while missing the mark on inflation has severely hemorrhaged its reputation, the fact that the Fed has turned into “too big a factor in determining economic outcomes” is the problem.

“I think that they deployed the airbag in March 2020. I believe that they did not understand, at the Federal Open Market Committee, the need to get the car back on the road,” the economist stated.

“I think the Fed is far too big a factor in determining economic outcomes. I think that it is exerting too much influence over financial markets.

After attempting to control the money supply by manipulating interest rates, the central bank’s only recourse in managing price stability “is to kill the economy.”

In this environment where many economic experts believe the Fed has destroyed its credibility by claiming for nearly a year that inflation would be transitory, is it time for changes to monetary policy?

The Federal Reserve building in Washington on Jan. 26, 2022. (Joshua Roberts/Reuters)

Shelton has not been shy about her support for fundamental monetary reforms.

In April 2019, Shelton wrote an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal titled “The Case for Monetary Regime Change.” She argued that it would be “entirely prudent to question the infallibility of the Federal Reserve in calibrating the money supply to the needs of the economy.”

Years later, she is still championing fundamental change at the Fed.

“I think that we might be reaching a point where people are so unhappy with the way the Fed has evolved into having such control over the economy, that they may be ready, now, to consider something along the lines of what was proposed and passed in the House in 2015, which was to have a monetary commission to really evaluate alternative monetary regimes,” Shelton averred.

“I really think central banking may have run its course. I think that we’re seeing that the tools the Fed uses now are damaging to productive economic activity.”

International

Acadia’s Nuplazid fails PhIII study due to higher-than-expected placebo effect

After years of trying to expand the market territory for Nuplazid, Acadia Pharmaceuticals might have hit a dead end, with a Phase III fail in schizophrenia…

After years of trying to expand the market territory for Nuplazid, Acadia Pharmaceuticals might have hit a dead end, with a Phase III fail in schizophrenia due to the placebo arm performing better than expected.

Steve Davis

Steve Davis“We will continue to analyze these data with our scientific advisors, but we do not intend to conduct any further clinical trials with pimavanserin,” CEO Steve Davis said in a Monday press release. Acadia’s stock $ACAD dropped by 17.41% before the market opened Tuesday.

Pimavanserin, a serotonin inverse agonist and also a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, is already in the market with the brand name Nuplazid for Parkinson’s disease psychosis. Efforts to expand into other indications such as Alzheimer’s-related psychosis and major depression have been unsuccessful, and previous trials in schizophrenia have yielded mixed data at best. Its February presentation does not list other pimavanserin studies in progress.

The Phase III ADVANCE-2 trial investigated 34 mg pimavanserin versus placebo in 454 patients who have negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The study used the negative symptom assessment-16 (NSA-16) total score as a primary endpoint and followed participants up to week 26. Study participants have control of positive symptoms due to antipsychotic therapies.

The company said that the change from baseline in this measure for the treatment arm was similar between the Phase II ADVANCE-1 study and ADVANCE-2 at -11.6 and -11.8, respectively. However, the placebo was higher in ADVANCE-2 at -11.1, when this was -8.5 in ADVANCE-1. The p-value in ADVANCE-2 was 0.4825.

In July last year, another Phase III schizophrenia trial — by Sumitomo and Otsuka — also reported negative results due to what the company noted as Covid-19 induced placebo effect.

According to Mizuho Securities analysts, ADVANCE-2 data were disappointing considering the company applied what it learned from ADVANCE-1, such as recruiting patients outside the US to alleviate a high placebo effect. The Phase III recruited participants in Argentina and Europe.

Analysts at Cowen added that the placebo effect has been a “notorious headwind” in US-based trials, which appears to “now extend” to ex-US studies. But they also noted ADVANCE-1 reported a “modest effect” from the drug anyway.

Nonetheless, pimavanserin’s safety profile in the late-stage study “was consistent with previous clinical trials,” with the drug having an adverse event rate of 30.4% versus 40.3% with placebo, the company said. Back in 2018, even with the FDA approval for Parkinson’s psychosis, there was an intense spotlight on Nuplazid’s safety profile.

Acadia previously aimed to get Nuplazid approved for Alzheimer’s-related psychosis but had many hurdles. The drug faced an adcomm in June 2022 that voted 9-3 noting that the drug is unlikely to be effective in this setting, culminating in a CRL a few months later.

As for the company’s next R&D milestones, Mizuho analysts said it won’t be anytime soon: There is the Phase III study for ACP-101 in Prader-Willi syndrome with data expected late next year and a Phase II trial for ACP-204 in Alzheimer’s disease psychosis with results anticipated in 2026.

Acadia collected $549.2 million in full-year 2023 revenues for Nuplazid, with $143.9 million in the fourth quarter.

depression covid-19 treatment fda clinical trials europeInternational

Four Years Ago This Week, Freedom Was Torched

Four Years Ago This Week, Freedom Was Torched

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Brownstone Institute,

"Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Brownstone Institute,

"Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare quotes the soothsayer’s warning Julius Caesar about what turned out to be an impending assassination on March 15. The death of American liberty happened around the same time four years ago, when the orders went out from all levels of government to close all indoor and outdoor venues where people gather.

It was not quite a law and it was never voted on by anyone. Seemingly out of nowhere, people who the public had largely ignored, the public health bureaucrats, all united to tell the executives in charge – mayors, governors, and the president – that the only way to deal with a respiratory virus was to scrap freedom and the Bill of Rights.

And they did, not only in the US but all over the world.

The forced closures in the US began on March 6 when the mayor of Austin, Texas, announced the shutdown of the technology and arts festival South by Southwest. Hundreds of thousands of contracts, of attendees and vendors, were instantly scrapped. The mayor said he was acting on the advice of his health experts and they in turn pointed to the CDC, which in turn pointed to the World Health Organization, which in turn pointed to member states and so on.

There was no record of Covid in Austin, Texas, that day but they were sure they were doing their part to stop the spread. It was the first deployment of the “Zero Covid” strategy that became, for a time, official US policy, just as in China.

It was never clear precisely who to blame or who would take responsibility, legal or otherwise.

This Friday evening press conference in Austin was just the beginning. By the next Thursday evening, the lockdown mania reached a full crescendo. Donald Trump went on nationwide television to announce that everything was under control but that he was stopping all travel in and out of US borders, from Europe, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. American citizens would need to return by Monday or be stuck.

Americans abroad panicked while spending on tickets home and crowded into international airports with waits up to 8 hours standing shoulder to shoulder. It was the first clear sign: there would be no consistency in the deployment of these edicts.

There is no historical record of any American president ever issuing global travel restrictions like this without a declaration of war. Until then, and since the age of travel began, every American had taken it for granted that he could buy a ticket and board a plane. That was no longer possible. Very quickly it became even difficult to travel state to state, as most states eventually implemented a two-week quarantine rule.

The next day, Friday March 13, Broadway closed and New York City began to empty out as any residents who could went to summer homes or out of state.

On that day, the Trump administration declared the national emergency by invoking the Stafford Act which triggers new powers and resources to the Federal Emergency Management Administration.

In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a classified document, only to be released to the public months later. The document initiated the lockdowns. It still does not exist on any government website.

The White House Coronavirus Response Task Force, led by the Vice President, will coordinate a whole-of-government approach, including governors, state and local officials, and members of Congress, to develop the best options for the safety, well-being, and health of the American people. HHS is the LFA [Lead Federal Agency] for coordinating the federal response to COVID-19.

Closures were guaranteed:

Recommend significantly limiting public gatherings and cancellation of almost all sporting events, performances, and public and private meetings that cannot be convened by phone. Consider school closures. Issue widespread ‘stay at home’ directives for public and private organizations, with nearly 100% telework for some, although critical public services and infrastructure may need to retain skeleton crews. Law enforcement could shift to focus more on crime prevention, as routine monitoring of storefronts could be important.

In this vision of turnkey totalitarian control of society, the vaccine was pre-approved: “Partner with pharmaceutical industry to produce anti-virals and vaccine.”

The National Security Council was put in charge of policy making. The CDC was just the marketing operation. That’s why it felt like martial law. Without using those words, that’s what was being declared. It even urged information management, with censorship strongly implied.

The timing here is fascinating. This document came out on a Friday. But according to every autobiographical account – from Mike Pence and Scott Gottlieb to Deborah Birx and Jared Kushner – the gathered team did not meet with Trump himself until the weekend of the 14th and 15th, Saturday and Sunday.

According to their account, this was his first real encounter with the urge that he lock down the whole country. He reluctantly agreed to 15 days to flatten the curve. He announced this on Monday the 16th with the famous line: “All public and private venues where people gather should be closed.”

This makes no sense. The decision had already been made and all enabling documents were already in circulation.

There are only two possibilities.

One: the Department of Homeland Security issued this March 13 HHS document without Trump’s knowledge or authority. That seems unlikely.

Two: Kushner, Birx, Pence, and Gottlieb are lying. They decided on a story and they are sticking to it.

Trump himself has never explained the timeline or precisely when he decided to greenlight the lockdowns. To this day, he avoids the issue beyond his constant claim that he doesn’t get enough credit for his handling of the pandemic.

With Nixon, the famous question was always what did he know and when did he know it? When it comes to Trump and insofar as concerns Covid lockdowns – unlike the fake allegations of collusion with Russia – we have no investigations. To this day, no one in the corporate media seems even slightly interested in why, how, or when human rights got abolished by bureaucratic edict.

As part of the lockdowns, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which was and is part of the Department of Homeland Security, as set up in 2018, broke the entire American labor force into essential and nonessential.

They also set up and enforced censorship protocols, which is why it seemed like so few objected. In addition, CISA was tasked with overseeing mail-in ballots.

Only 8 days into the 15, Trump announced that he wanted to open the country by Easter, which was on April 12. His announcement on March 24 was treated as outrageous and irresponsible by the national press but keep in mind: Easter would already take us beyond the initial two-week lockdown. What seemed to be an opening was an extension of closing.

This announcement by Trump encouraged Birx and Fauci to ask for an additional 30 days of lockdown, which Trump granted. Even on April 23, Trump told Georgia and Florida, which had made noises about reopening, that “It’s too soon.” He publicly fought with the governor of Georgia, who was first to open his state.

Before the 15 days was over, Congress passed and the president signed the 880-page CARES Act, which authorized the distribution of $2 trillion to states, businesses, and individuals, thus guaranteeing that lockdowns would continue for the duration.

There was never a stated exit plan beyond Birx’s public statements that she wanted zero cases of Covid in the country. That was never going to happen. It is very likely that the virus had already been circulating in the US and Canada from October 2019. A famous seroprevalence study by Jay Bhattacharya came out in May 2020 discerning that infections and immunity were already widespread in the California county they examined.

What that implied was two crucial points: there was zero hope for the Zero Covid mission and this pandemic would end as they all did, through endemicity via exposure, not from a vaccine as such. That was certainly not the message that was being broadcast from Washington. The growing sense at the time was that we all had to sit tight and just wait for the inoculation on which pharmaceutical companies were working.

By summer 2020, you recall what happened. A restless generation of kids fed up with this stay-at-home nonsense seized on the opportunity to protest racial injustice in the killing of George Floyd. Public health officials approved of these gatherings – unlike protests against lockdowns – on grounds that racism was a virus even more serious than Covid. Some of these protests got out of hand and became violent and destructive.

Meanwhile, substance abuse rage – the liquor and weed stores never closed – and immune systems were being degraded by lack of normal exposure, exactly as the Bakersfield doctors had predicted. Millions of small businesses had closed. The learning losses from school closures were mounting, as it turned out that Zoom school was near worthless.

It was about this time that Trump seemed to figure out – thanks to the wise council of Dr. Scott Atlas – that he had been played and started urging states to reopen. But it was strange: he seemed to be less in the position of being a president in charge and more of a public pundit, Tweeting out his wishes until his account was banned. He was unable to put the worms back in the can that he had approved opening.

By that time, and by all accounts, Trump was convinced that the whole effort was a mistake, that he had been trolled into wrecking the country he promised to make great. It was too late. Mail-in ballots had been widely approved, the country was in shambles, the media and public health bureaucrats were ruling the airwaves, and his final months of the campaign failed even to come to grips with the reality on the ground.

At the time, many people had predicted that once Biden took office and the vaccine was released, Covid would be declared to have been beaten. But that didn’t happen and mainly for one reason: resistance to the vaccine was more intense than anyone had predicted. The Biden administration attempted to impose mandates on the entire US workforce. Thanks to a Supreme Court ruling, that effort was thwarted but not before HR departments around the country had already implemented them.

As the months rolled on – and four major cities closed all public accommodations to the unvaccinated, who were being demonized for prolonging the pandemic – it became clear that the vaccine could not and would not stop infection or transmission, which means that this shot could not be classified as a public health benefit. Even as a private benefit, the evidence was mixed. Any protection it provided was short-lived and reports of vaccine injury began to mount. Even now, we cannot gain full clarity on the scale of the problem because essential data and documentation remains classified.

After four years, we find ourselves in a strange position. We still do not know precisely what unfolded in mid-March 2020: who made what decisions, when, and why. There has been no serious attempt at any high level to provide a clear accounting much less assign blame.

Not even Tucker Carlson, who reportedly played a crucial role in getting Trump to panic over the virus, will tell us the source of his own information or what his source told him. There have been a series of valuable hearings in the House and Senate but they have received little to no press attention, and none have focus on the lockdown orders themselves.

The prevailing attitude in public life is just to forget the whole thing. And yet we live now in a country very different from the one we inhabited five years ago. Our media is captured. Social media is widely censored in violation of the First Amendment, a problem being taken up by the Supreme Court this month with no certainty of the outcome. The administrative state that seized control has not given up power. Crime has been normalized. Art and music institutions are on the rocks. Public trust in all official institutions is at rock bottom. We don’t even know if we can trust the elections anymore.

In the early days of lockdown, Henry Kissinger warned that if the mitigation plan does not go well, the world will find itself set “on fire.” He died in 2023. Meanwhile, the world is indeed on fire. The essential struggle in every country on earth today concerns the battle between the authority and power of permanent administration apparatus of the state – the very one that took total control in lockdowns – and the enlightenment ideal of a government that is responsible to the will of the people and the moral demand for freedom and rights.

How this struggle turns out is the essential story of our times.

CODA: I’m embedding a copy of PanCAP Adapted, as annotated by Debbie Lerman. You might need to download the whole thing to see the annotations. If you can help with research, please do.

* * *

Jeffrey Tucker is the author of the excellent new book 'Life After Lock-Down'

International

Red Candle In The Wind

Red Candle In The Wind

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by…

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by printing at 275,000 against a consensus call of 200,000. We say superficially, because the downward revisions to prior months totalled 167,000 for December and January, taking the total change in employed persons well below the implied forecast, and helping the unemployment rate to pop two-ticks to 3.9%. The U6 underemployment rate also rose from 7.2% to 7.3%, while average hourly earnings growth fell to 0.2% m-o-m and average weekly hours worked languished at 34.3, equalling pre-pandemic lows.

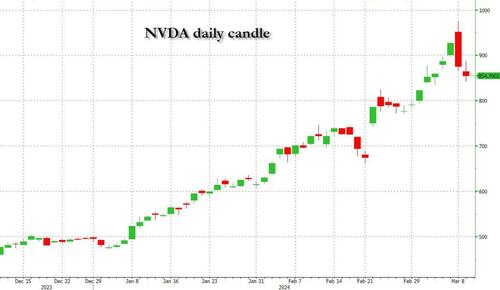

Undeterred by the devil in the detail, the algos sprang into action once exchanges opened. Market darling NVIDIA hit a new intraday high of $974 before (presumably) the humans took over and sold the stock down more than 10% to close at $875.28. If our suspicions are correct that it was the AIs buying before the humans started selling (no doubt triggering trailing stops on the way down), the irony is not lost on us.

The 1-day chart for NVIDIA now makes for interesting viewing, because the red candle posted on Friday presents quite a strong bearish engulfing signal. Volume traded on the day was almost double the 15-day simple moving average, and similar price action is observable on the 1-day charts for both Intel and AMD. Regular readers will be aware that we have expressed incredulity in the past about the durability the AI thematic melt-up, so it will be interesting to see whether Friday’s sell off is just a profit-taking blip, or a genuine trend reversal.

AI equities aside, this week ought to be important for markets because the BTFP program expires today. That means that the Fed will no longer be loaning cash to the banking system in exchange for collateral pledged at-par. The KBW Regional Banking index has so far taken this in its stride and is trading 30% above the lows established during the mini banking crisis of this time last year, but the Fed’s liquidity facility was effectively an exercise in can-kicking that makes regional banks a sector of the market worth paying attention to in the weeks ahead. Even here in Sydney, regulators are warning of external risks posed to the banking sector from scheduled refinancing of commercial real estate loans following sharp falls in valuations.

Markets are sending signals in other sectors, too. Gold closed at a new record-high of $2178/oz on Friday after trading above $2200/oz briefly. Gold has been going ballistic since the Friday before last, posting gains even on days where 2-year Treasury yields have risen. Gold bugs are buying as real yields fall from the October highs and inflation breakevens creep higher. This is particularly interesting as gold ETFs have been recording net outflows; suggesting that price gains aren’t being driven by a retail pile-in. Are gold buyers now betting on a stagflationary outcome where the Fed cuts without inflation being anchored at the 2% target? The price action around the US CPI release tomorrow ought to be illuminating.

Leaving the day-to-day movements to one side, we are also seeing further signs of structural change at the macro level. The UK budget last week included a provision for the creation of a British ISA. That is, an Individual Savings Account that provides tax breaks to savers who invest their money in the stock of British companies. This follows moves last year to encourage pension funds to head up the risk curve by allocating 5% of their capital to unlisted investments.

As a Hail Mary option for a government cruising toward an electoral drubbing it’s a curious choice, but it’s worth highlighting as cash-strapped governments increasingly see private savings pools as a funding solution for their spending priorities.

Of course, the UK is not alone in making creeping moves towards financial repression. In contrast to announcements today of increased trade liberalisation, Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers has in the recent past flagged his interest in tapping private pension savings to fund state spending priorities, including defence, public housing and renewable energy projects. Both the UK and Australia appear intent on finding ways to open up the lungs of their economies, but government wants more say in directing private capital flows for state goals.

So, how far is the blurring of the lines between free markets and state planning likely to go? Given the immense and varied budgetary (and security) pressures that governments are facing, could we see a re-up of WWII-era Victory bonds, where private investors are encouraged to do their patriotic duty by directly financing government at negative real rates?

That would really light a fire under the gold market.

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges