International

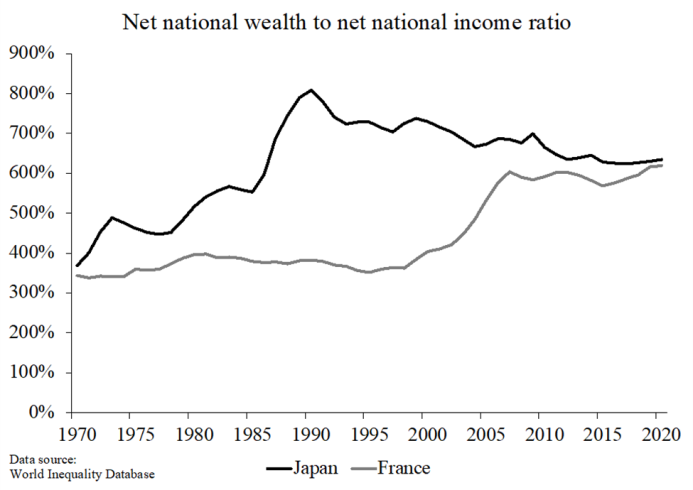

France Is Catching Up to Japan, but Not in a Good Way

Inequality and social mobility are hotly debated issues. One important indicator of social mobility are wealth-to-income ratios. If a country’s wealth-to-income…

Inequality and social mobility are hotly debated issues. One important indicator of social mobility are wealth-to-income ratios. If a country’s wealth-to-income ratio is high, the country is not necessarily wealthy. It merely implies that the monetary value of all assets in that country is relatively high compared to the incomes earned. The higher the wealth-to-income ratio, the harder it gets to climb the social ladder, if one starts from the bottom. It takes more years of work and income to reach any given position in the wealth distribution of society. France and Japan are today among the developed countries with the highest wealth-to-income ratios.

Since the introduction of the euro in 1999, the wealth-to-income ratio in France has been on the same trajectory as it had been in Japan fifteen years earlier during the country’s massive asset price bubble of the 1980s. In France, there was an even weaker price correction after the Great Recession as the European Central Bank stepped in quickly to keep asset prices artificially afloat through unconventional monetary policy measures. Even though France’s wealth-to-income ratio at its peak never reached Japan’s peak of 808 percent in 1990, today they nearly match at 634 percent in Japan and 620 percent in France.1

Overall net wealth in France is thus more than 6 times as big as net annual income. This is a relatively high value compared to other developed countries. In the United States, the wealth-to-income ratio stands at 532 percent, slightly above that of Germany (520 percent) and below that of the UK (576 percent). In all of these countries the trend is positive over the past decades, but France is the most striking case. In 1998, the year before the euro was introduced, the French wealth-to-income ratio was only 363 percent. In less than ten years, on the brink of the Great Recession in 2007, it reached 604 percent. This development is largely driven by monetary policy. The implementation of a common currency area combined with more than a doubling the M1 money stock within that area in only nine years,2 has mobilized a lot of financial capital that flooded the southern European asset markets, including those of France.

Monetary policy around the world targets a positive rate of price inflation. This has systematic effects on how people save. Even with moderate rates of price inflation, the opportunity costs of holding savings on deposit accounts increase. As the purchasing power of money is continuously reduced, people face an added incentive to direct a higher proportion of their savings into financial and non-financial assets that might serve as a hedge against this loss. Inflationary monetary policy thus generates an added demand for all kinds of assets that goes beyond the effects of the mere increase in the stock of money. This added demand pushes up asset prices disproportionately. Very visible incidences of this tendency are overproportionate rates of price inflation in stock and real estate markets.

With the coronavirus outbreak, aggressive monetary easing by central banks has continued to become the new normal. Real estate prices in Japan and France are on the rise again. In the Tokyo metropolitan area, last year’s price per square meter (€7.293 per square meter) has exceeded its all-time high set at the peak of the asset-inflated bubble economy three decades ago (€7.280 per square meter). Meanwhile, the price per square meter in Paris has climbed up to €11.885, with the French house price index reaching an all-time high.

Overproportionate asset price inflation has many further implications, one of them being the increase of the wealth-to-income ratio over and above the point at which it would otherwise stand. This is important in many respects, not least from the vantage point of social policy, because a rising wealth-to-income ratio tends to undermine upward social mobility, in particular when the wealth distribution is very unequal. And this is the case in most countries with a large proportion of households owning practically nothing.

Let us apply a back-of-the-envelope calculation to illustrate the problem: If the wealth-to-income ratio is 620 percent as in France in 2020, you have an average income and no wealth and start saving 10 percent of your income today, then it would take you sixty-two years to reach the average wealth level of society. In France in 1998, it would have taken only thirty-six years. Back then it was much more realistic to achieve the average level of wealth within a working life starting from zero. In this calculation, we abstract from any heterogeneity in inflation rates and assume that all prices, including all incomes, increase at the same rate over time.

Under these ceteris paribus conditions, our representative French income earner with a 10 percent saving rate would need sixty-two years to build up wealth amounting to the equivalent of €176.803. This would buy a meager fifteen square meters in Paris. In spite of the common perception of being a country of equality and social justice, it becomes clear that it is particularly difficult in France to climb up the social ladder if one comes from a modest background. This is also because net incomes are particularly low due to high taxes and social security payments. In France, more so than in other places, it is better to be born with a silver spoon in one’s mouth. If you own wealth already, you are not afraid of overproportionate asset price inflation. You tend to benefit from it. Your own privileged position in the social hierarchy is strengthened. As it becomes harder for people to make it to the top, it also becomes easier to stay on top for those who are already there.

In Japan, the picture is quite similar. During its high growth period (1954–72) individual economic endeavors were adequately rewarded. Climbing up the social ladder was a real possibility. However, with the lost three decades, this has drastically changed. The inhibited upward social mobility is even couched in the Japanese slang term “oya-gacha,” which has come into such an extensive use that it was a contender for last year’s buzzword of the year. It captures the notion that life is like a lottery—winning or losing, like in France, depends mostly on who your parents are.

The social and economic consequences of an inhibited upward social mobility are profound, especially when the causes are not well understood. It is common to blame the market economy for all kinds of social problems, foremost among them are rising inequality and falling social mobility. But all too often political interventions into the economic system cause these unintended consequences. In the context of social mobility, a lot would be gained if monetary policy would be more restrictive preventing disproportionately high asset price inflation.

- 1. Data are taken from the World Inequality Database.

- 2. From the end of 1998 to the end of 2007, the M1 money stock has on average increased by 9.1 percent annually within the euro area. The money stock has thus grown by a factor of 2.2 overall.

International

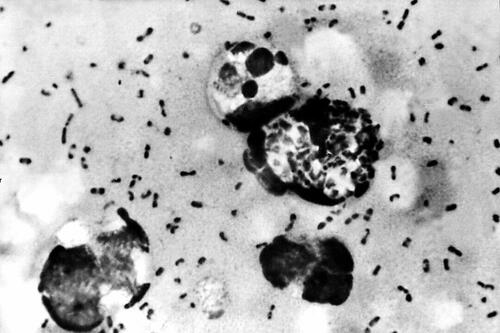

Health Officials: Man Dies From Bubonic Plague In New Mexico

Health Officials: Man Dies From Bubonic Plague In New Mexico

Authored by Jack Phillips via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Officials in…

Authored by Jack Phillips via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Officials in New Mexico confirmed that a resident died from the plague in the United States’ first fatal case in several years.

The New Mexico Department of Health, in a statement, said that a man in Lincoln County “succumbed to the plague.” The man, who was not identified, was hospitalized before his death, officials said.

They further noted that it is the first human case of plague in New Mexico since 2021 and also the first death since 2020, according to the statement. No other details were provided, including how the disease spread to the man.

The agency is now doing outreach in Lincoln County, while “an environmental assessment will also be conducted in the community to look for ongoing risk,” the statement continued.

“This tragic incident serves as a clear reminder of the threat posed by this ancient disease and emphasizes the need for heightened community awareness and proactive measures to prevent its spread,” the agency said.

A bacterial disease that spreads via rodents, it is generally spread to people through the bites of infected fleas. The plague, known as the black death or the bubonic plague, can spread by contact with infected animals such as rodents, pets, or wildlife.

The New Mexico Health Department statement said that pets such as dogs and cats that roam and hunt can bring infected fleas back into homes and put residents at risk.

Officials warned people in the area to “avoid sick or dead rodents and rabbits, and their nests and burrows” and to “prevent pets from roaming and hunting.”

“Talk to your veterinarian about using an appropriate flea control product on your pets as not all products are safe for cats, dogs or your children” and “have sick pets examined promptly by a veterinarian,” it added.

“See your doctor about any unexplained illness involving a sudden and severe fever, the statement continued, adding that locals should clean areas around their home that could house rodents like wood piles, junk piles, old vehicles, and brush piles.

The plague, which is spread by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, famously caused the deaths of an estimated hundreds of millions of Europeans in the 14th and 15th centuries following the Mongol invasions. In that pandemic, the bacteria spread via fleas on black rats, which historians say was not known by the people at the time.

Other outbreaks of the plague, such as the Plague of Justinian in the 6th century, are also believed to have killed about one-fifth of the population of the Byzantine Empire, according to historical records and accounts. In 2013, researchers said the Justinian plague was also caused by the Yersinia pestis bacteria.

But in the United States, it is considered a rare disease and usually occurs only in several countries worldwide. Generally, according to the Mayo Clinic, the bacteria affects only a few people in U.S. rural areas in Western states.

Recent cases have occurred mainly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Countries with frequent plague cases include Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Peru, the clinic says. There were multiple cases of plague reported in Inner Mongolia, China, in recent years, too.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a bubonic plague infection include headache, chills, fever, and weakness. Health officials say it can usually cause a painful swelling of lymph nodes in the groin, armpit, or neck areas. The swelling usually occurs within about two to eight days.

The disease can generally be treated with antibiotics, but it is usually deadly when not treated, the Mayo Clinic website says.

“Plague is considered a potential bioweapon. The U.S. government has plans and treatments in place if the disease is used as a weapon,” the website also says.

According to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the last time that plague deaths were reported in the United States was in 2020 when two people died.

International

Riley Gaines Explains How Women’s Sports Are Rigged To Promote The Trans Agenda

Riley Gaines Explains How Women’s Sports Are Rigged To Promote The Trans Agenda

Is there a light forming when it comes to the long, dark and…

Is there a light forming when it comes to the long, dark and bewildering tunnel of social justice cultism? Global events have been so frenetic that many people might not remember, but only a couple years ago Big Tech companies and numerous governments were openly aligned in favor of mass censorship. Not just to prevent the public from investigating the facts surrounding the pandemic farce, but to silence anyone questioning the validity of woke concepts like trans ideology.

From 2020-2022 was the closest the west has come in a long time to a complete erasure of freedom of speech. Even today there are still countries and Europe and places like Canada or Australia that are charging forward with draconian speech laws. The phrase "radical speech" is starting to circulate within pro-censorship circles in reference to any platform where people are allowed to talk critically. What is radical speech? Basically, it's any discussion that runs contrary to the beliefs of the political left.

Open hatred of moderate or conservative ideals is perfectly acceptable, but don't ever shine a negative light on woke activism, or you might be a terrorist.

Riley Gaines has experienced this double standard first hand. She was even assaulted and taken hostage at an event in 2023 at San Francisco State University when leftists protester tried to trap her in a room and demanded she "pay them to let her go." Campus police allegedly witnessed the incident but charges were never filed and surveillance footage from the college was never released.

It's probably the last thing a champion female swimmer ever expects, but her head-on collision with the trans movement and the institutional conspiracy to push it on the public forced her to become a counter-culture voice of reason rather than just an athlete.

For years the independent media argued that no matter how much we expose the insanity of men posing as women to compete and dominate women's sports, nothing will really change until the real female athletes speak up and fight back. Riley Gaines and those like her represent that necessary rebellion and a desperately needed return to common sense and reason.

In a recent interview on the Joe Rogan Podcast, Gaines related some interesting information on the inner workings of the NCAA and the subversive schemes surrounding trans athletes. Not only were women participants essentially strong-armed by colleges and officials into quietly going along with the program, there was also a concerted propaganda effort. Competition ceremonies were rigged as vehicles for promoting trans athletes over everyone else.

The bottom line? The competitions didn't matter. The real women and their achievements didn't matter. The only thing that mattered to officials were the photo ops; dudes pretending to be chicks posing with awards for the gushing corporate media. The agenda took precedence.

Lia Thomas, formerly known as William Thomas, was more than an activist invading female sports, he was also apparently a science project fostered and protected by the athletic establishment. It's important to understand that the political left does not care about female athletes. They do not care about women's sports. They don't care about the integrity of the environments they co-opt. Their only goal is to identify viable platforms with social impact and take control of them. Women's sports are seen as a vehicle for public indoctrination, nothing more.

The reasons why they covet women's sports are varied, but a primary motive is the desire to assert the fallacy that men and women are "the same" psychologically as well as physically. They want the deconstruction of biological sex and identity as nothing more than "social constructs" subject to personal preference. If they can destroy what it means to be a man or a woman, they can destroy the very foundations of relationships, families and even procreation.

For now it seems as though the trans agenda is hitting a wall with much of the public aware of it and less afraid to criticize it. Social media companies might be able to silence some people, but they can't silence everyone. However, there is still a significant threat as the movement continues to target children through the public education system and women's sports are not out of the woods yet.

The ultimate solution is for women athletes around the world to organize and widely refuse to participate in any competitions in which biological men are allowed. The only way to save women's sports is for women to be willing to end them, at least until institutions that put doctrine ahead of logic are made irrelevant.

International

Congress’ failure so far to deliver on promise of tens of billions in new research spending threatens America’s long-term economic competitiveness

A deal that avoided a shutdown also slashed spending for the National Science Foundation, putting it billions below a congressional target intended to…

Federal spending on fundamental scientific research is pivotal to America’s long-term economic competitiveness and growth. But less than two years after agreeing the U.S. needed to invest tens of billions of dollars more in basic research than it had been, Congress is already seriously scaling back its plans.

A package of funding bills recently passed by Congress and signed by President Joe Biden on March 9, 2024, cuts the current fiscal year budget for the National Science Foundation, America’s premier basic science research agency, by over 8% relative to last year. That puts the NSF’s current allocation US$6.6 billion below targets Congress set in 2022.

And the president’s budget blueprint for the next fiscal year, released on March 11, doesn’t look much better. Even assuming his request for the NSF is fully funded, it would still, based on my calculations, leave the agency a total of $15 billion behind the plan Congress laid out to help the U.S. keep up with countries such as China that are rapidly increasing their science budgets.

I am a sociologist who studies how research universities contribute to the public good. I’m also the executive director of the Institute for Research on Innovation and Science, a national university consortium whose members share data that helps us understand, explain and work to amplify those benefits.

Our data shows how underfunding basic research, especially in high-priority areas, poses a real threat to the United States’ role as a leader in critical technology areas, forestalls innovation and makes it harder to recruit the skilled workers that high-tech companies need to succeed.

A promised investment

Less than two years ago, in August 2022, university researchers like me had reason to celebrate.

Congress had just passed the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act. The science part of the law promised one of the biggest federal investments in the National Science Foundation in its 74-year history.

The CHIPS act authorized US$81 billion for the agency, promised to double its budget by 2027 and directed it to “address societal, national, and geostrategic challenges for the benefit of all Americans” by investing in research.

But there was one very big snag. The money still has to be appropriated by Congress every year. Lawmakers haven’t been good at doing that recently. As lawmakers struggle to keep the lights on, fundamental research is quickly becoming a casualty of political dysfunction.

Research’s critical impact

That’s bad because fundamental research matters in more ways than you might expect.

For instance, the basic discoveries that made the COVID-19 vaccine possible stretch back to the early 1960s. Such research investments contribute to the health, wealth and well-being of society, support jobs and regional economies and are vital to the U.S. economy and national security.

Lagging research investment will hurt U.S. leadership in critical technologies such as artificial intelligence, advanced communications, clean energy and biotechnology. Less support means less new research work gets done, fewer new researchers are trained and important new discoveries are made elsewhere.

But disrupting federal research funding also directly affects people’s jobs, lives and the economy.

Businesses nationwide thrive by selling the goods and services – everything from pipettes and biological specimens to notebooks and plane tickets – that are necessary for research. Those vendors include high-tech startups, manufacturers, contractors and even Main Street businesses like your local hardware store. They employ your neighbors and friends and contribute to the economic health of your hometown and the nation.

Nearly a third of the $10 billion in federal research funds that 26 of the universities in our consortium used in 2022 directly supported U.S. employers, including:

A Detroit welding shop that sells gases many labs use in experiments funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Department of Defense and Department of Energy.

A Dallas-based construction company that is building an advanced vaccine and drug development facility paid for by the Department of Health and Human Services.

More than a dozen Utah businesses, including surveyors, engineers and construction and trucking companies, working on a Department of Energy project to develop breakthroughs in geothermal energy.

When Congress shortchanges basic research, it also damages businesses like these and people you might not usually associate with academic science and engineering. Construction and manufacturing companies earn more than $2 billion each year from federally funded research done by our consortium’s members.

Jobs and innovation

Disrupting or decreasing research funding also slows the flow of STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – talent from universities to American businesses. Highly trained people are essential to corporate innovation and to U.S. leadership in key fields, such as AI, where companies depend on hiring to secure research expertise.

In 2022, federal research grants paid wages for about 122,500 people at universities that shared data with my institute. More than half of them were students or trainees. Our data shows that they go on to many types of jobs but are particularly important for leading tech companies such as Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Intel.

That same data lets me estimate that over 300,000 people who worked at U.S. universities in 2022 were paid by federal research funds. Threats to federal research investments put academic jobs at risk. They also hurt private sector innovation because even the most successful companies need to hire people with expert research skills. Most people learn those skills by working on university research projects, and most of those projects are federally funded.

High stakes

If Congress doesn’t move to fund fundamental science research to meet CHIPS and Science Act targets – and make up for the $11.6 billion it’s already behind schedule – the long-term consequences for American competitiveness could be serious.

Over time, companies would see fewer skilled job candidates, and academic and corporate researchers would produce fewer discoveries. Fewer high-tech startups would mean slower economic growth. America would become less competitive in the age of AI. This would turn one of the fears that led lawmakers to pass the CHIPS and Science Act into a reality.

Ultimately, it’s up to lawmakers to decide whether to fulfill their promise to invest more in the research that supports jobs across the economy and in American innovation, competitiveness and economic growth. So far, that promise is looking pretty fragile.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 16, 2024.

Jason Owen-Smith receives research support from the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Wellcome Leap.

economic growth covid-19 grants congress vaccine china-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International6 days ago

International6 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International6 days ago

International6 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges