The world is now in the grips of a historic pandemic. The death toll from the novel coronavirus has climbed to more than 117,000 in the United States and 448,000 around the world. Total cases of the disease, called COVID-19, have soared past 2 million in the US and 8.3 million globally. Debates are now raging about whether US states have begun to move too quickly to reopen restaurants, stores, barbershops, and the myriad other engines of life and commerce after weeks of lockdown.

But there is one area of widespread agreement, says Robert Tjian, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at the University of California, Berkeley: the safe path out of the pandemic requires enormous amounts of testing. In the May 1, 2020, issue of the journal RNA, Tjian, study coauthor Meagan Esbin, and their colleagues reviewed recent advances in COVID-19 testing techniques and highlighted barriers facing widespread testing. To trace the pathogen’s spread and stop the chain of transmission, it’s crucial to test both for the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself and for evidence that people have previously been infected, Tjian explains.

The countries that have so far successfully quashed their outbreaks, such as New Zealand, Taiwan, South Korea, and Iceland, have done the best job of identifying cases. In contrast, “the United States has done quite poorly,” says Lawrence Gostin, professor of medicine and public health expert at Georgetown University.

That failing is not for lack of effort in the scientific community. Scores of researchers around the country have dropped what they were doing to tackle the challenge in the US, Tjian says. In fact, he adds, in compiling the many studies described in his group’s paper, he was “surprised at how quickly so many labs have converted to working on COVID-19.”

These labs have devised innovative new approaches for testing, as well as for overcoming the bottlenecks that hampered testing efforts early in the pandemic. Some labs, like at Berkeley, have set up their own rapid testing operations to serve local communities, quickly publishing their methods “so that everyone doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel,” says Tjian. These and many other efforts are helping to answer some of the basic questions about fighting the pandemic.

Why is testing so important?

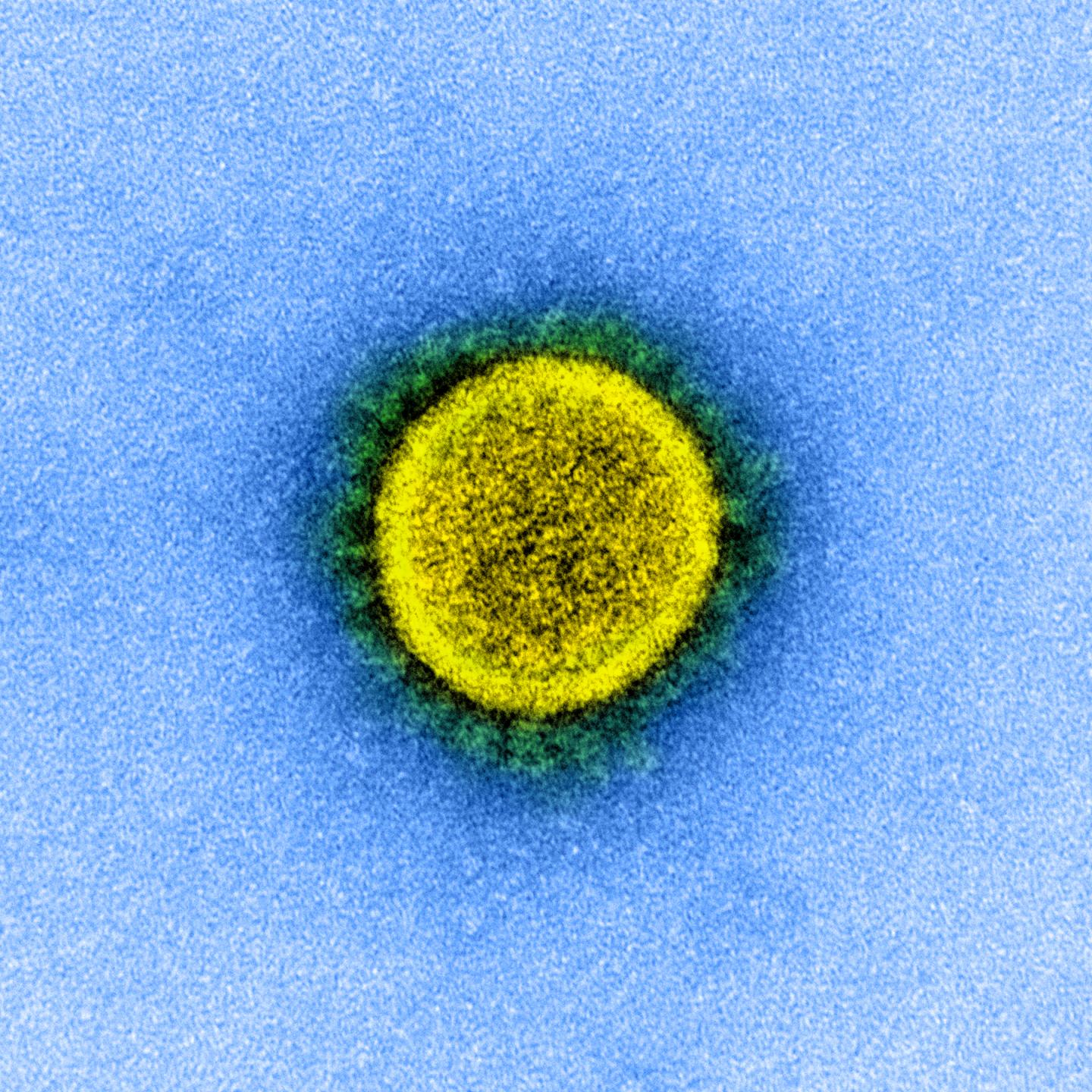

SARS-CoV-2 is an especially pernicious virus. It is both highly contagious and relatively lethal, with a mortality rate that’s still uncertain but higher than that of flu – 10 times or more higher, some data suggest. But the virus’s wiliest feature is that it can be spread by people who don’t even know they are infected. In contrast, victims of the original SARS virus in 2003 weren’t contagious until severe symptoms struck, making it easy to isolate those people and cut the chain of transmission.

In the United States, the number of confirmed coronavirus cases has surpassed two million. Case density shown in red. View full dashboard with case tally by country. Credit: Johns Hopkins University

“That people can have COVID-19 without symptoms is one of the most challenging aspects of preventing spread,” explains Eric Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. One unknowingly infected person can infect dozens of others, as shown by “superspreading” events like a choir practice in Washington state, with 32 confirmed cases, and a man who visited several South Korean nightclubs, infecting more than 100 people.

In addition, testing may spot SARS-CoV-2 only when an infected person is actively producing lots of the virus, says Tjian. That’s why three types of testing are vital, he says. People with any COVID-19 symptoms should be tested, to spot new cases as soon as possible. People who have been in contact with an infected person also should be tested, even if they have no symptoms. And finally, he says, health care providers should test people for antibodies to the virus, to identify those who may have already been infected.

How do scientists test for the new coronavirus?

SARS-CoV-2 reproduces by getting into human cells, then hijacking the cells’ machinery to make many copies of its genetic material, called RNA. Scientists have designed several testing methods to spot this distinctive viral RNA. The method used in almost all testing to date and considered the “gold standard” relies on a technique for amplifying tiny amounts of viral genes. First, a swab collects infected cells from a person’s throat, gathering bits of viral RNA. That genetic material is typically purified and then copied from RNA into complementary DNA. The DNA is then copied millions of times using a standard method known as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Finally, a fluorescent probe is added that emits a telltale glow when DNA copies of the viral RNA are present.

PCR isn’t the only viable approach. Scientists at MIT and other universities have also repurposed the gene editing technique called CRISPR to quickly detect SARS-CoV-2. CRISPR uses engineered enzymes to cut DNA at precise spots. The testing approach harnesses that ability to hunt for a specific bit of genetic code, in this case a viral RNA, using an enzyme that fluoresces when it finds the distinctive SARS-CoV-2 target. In early May, the Food and Drug Administration gave emergency authorization to the test developed by the MIT team, which is led by HHMI Investigator Feng Zhang.

Another testing technique quickly reads each RNA “letter” of the viral genome, using a process called genetic sequencing. That’s overkill for detecting the virus, but it has been particularly helpful at charting the virus’s relentless march around the globe. And some researchers are experimenting with clever DNA “nanoswitches” that can flip from one shape to another and generate a fluorescent glow when they spot a piece of viral RNA.

Scientists can also see telltale signs of infection in the blood. Once people have been infected, their immune systems respond by creating antibodies designed to neutralize the virus. Antibody tests detect that immune response in blood samples using a protein engineered to bind to SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Creating an antibody test that’s both sensitive and accurate can be tricky, however.

Though coronavirus testing in the US has struggled to reach the levels needed, “the science is not the complicated part,” says Tjian. “Like anything else in research, there is more than one solution.” Instead, the real problem has been accelerating the pace of testing.

What is the US’s track record on testing?

Even as the virus rampaged through Wuhan, China, in January 2020 and started to kill Americans in February (or perhaps even earlier), the US government failed to prepare for the spreading pandemic. There was essentially “no response” from the federal government, Tjian says. “You could not have imagined a worse leadership team to be dealing with this worldwide pandemic.”

The Trump Administration declined to use a PCR-based test developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), for example, and a test produced by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) turned out to be faulty. The lack of a coordinated national effort left states, companies, and university labs scrambling to fill the gap.

As labs and states in the US raced to boost their testing capabilities, they ran into bottlenecks and roadblocks. For example, “only a few supply houses were providing the reagents [needed for the PCR reactions] and supplies were woefully inadequate,” says Tjian. Even basic equipment, like the swabs used for collecting samples, was hard to find. “That was one thing that caught us by surprise,” recalls Tjian. “Who would have imagined that the most rate-limited piece of this whole puzzle was the swab?” It turned out that the major producer of swabs approved by the CDC was a factory in northern Italy, a region among those hardest hit by the virus.

Without sufficient testing, there was a “tragic data gap undermining the U.S. pandemic response,” writes health service researcher Eric C. Schneider in a commentary in the May 15 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. Instead of being able to test every person with symptoms and all those they had been in contact with, as countries like South Korea did, the shortage meant reserving tests for hospitalized patients and for helping prevent health care workers from transmitting COVID-19, he explains.

The lack of data on case numbers has made it challenging to model the path of the pandemic, writes Schneider, of the Commonwealth Fund, a private foundation aimed at improving the health care system. As a result, it has been difficult to anticipate where emergency medical services, hospital beds, and ventilators are most needed.

By mid-May, the testing capacity in the US had finally risen from a few thousand a day to about 300,000 a day. Still, that’s far short of what’s needed. The Harvard Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience estimates, for example, that the country will require testing at a rate of “20 million a day to fully remobilize the economy.” To safely reopen, “we need massive testing capacities don’t currently exist,” says Georgetown’s Gostin, one of the authors of the report.

How can scientists overcome testing bottlenecks?

Scientists around the world have responded to the challenges posed by the novel coronavirus. The Berkeley group, for example, dramatically boosted its testing capacity and reduced costs to near $1 per test with improvements such as skipping one step – RNA purification – and making their own reagents. “It’s not rocket science, but it took us five weeks to figure out the details because commercial companies don’t tell you what’s in their reagents,” explains Tjian. The research team has made their home-brewed test freely available to any lab that wants to replicate it.

Meanwhile, groups at Rutgers, Yale (including HHMI Investigator Akiko Iwasaki), and other centers have eliminated the need for throat swabs by showing that saliva samples work just as well. That opens the door to home testing wider, since spitting into a tube and mailing it to a lab is far easier than swabbing.

Progress is also being made in testing for antibodies. Most of the dozens of so-called serology tests initially on the market didn’t have the sensitivity and specificity to pick out only those antibodies directed at SARS-CoV-2. The challenge is that the tests require using copies of a viral protein that binds to the antibodies. One key to solving that problem, it turns out, is using mammalian cells to make the viral protein with the precise shape needed to home in on just the SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

How will testing help tame the pandemic?

The basic strategy for overcoming COVID-19 is identifying infected people, finding and testing anyone they came in contact with, and quarantining infected individuals. That’s not practical for big cities or entire countries, given the staggering numbers of needed tests, logistical challenges, and thorny privacy issues. But there are clever ways to cast a wider net without so many individual tests.

One is lumping together many samples in a pool, so that large groups of people can be monitored with only one test. Then, if the virus does show up in the pool, public health officials can test the individuals in that group to pinpoint the infections.

Perhaps even more powerful is monitoring sewage. The virus can appear in a person’s feces within three days of infection – far earlier than the onset of first symptoms. Scientists could use the standard PCR test on sewage samples to detect the virus. And by collecting samples from specific locations, such as manholes, scattered throughout a community, it would be possible to narrow down the location of any infections to a few blocks or even individual buildings, like an apartment complex or a college dorm. “You can determine the viral load and how it is changing over time with one test a day,” says Tjian. “That would be amazing.”

Tjian and many others are now figuring out how these approaches might be used to safely reopen a university or a business. Large-scale testing efforts would be labor-intensive and not inexpensive, he says, but far cheaper than locking down a whole economy – and far safer than reopening without adequate testing, as some states are now doing. And as scientists continue to increase testing capacities and create cheaper and better tests, this strategy should soon be within reach.

###

Citation

M.N. Esbin et al. “Overcoming the bottleneck to widespread testing: A rapid review of nucleic acid testing approaches for COVID-19 detection.” Published online in RNA May 1, 2020. doi: 10.1261/rna.076232.120.