Uncategorized

Death From Overfunding: An Obituary For Convoy

Death From Overfunding: An Obituary For Convoy

By Craig Fuller, CEO of FreightWaves

The death of Convoy has been one of the biggest stories…

By Craig Fuller, CEO of FreightWaves

The death of Convoy has been one of the biggest stories in both tech and freight media over the past week. While the freight market has suffered a number of major shutdowns, few were as sudden as Convoy’s.

After all, Yellow was a much bigger company, but it died a very slow death, and because it was a publicly traded company, we all got to watch its journey on life support for many years. Convoy’s story, on the other hand, offers a cautionary tale of a meteoric rise to burnout in just eight years. For most of that time, it was respected, loathed and feared by industry insiders, both wary and weary of how a war chest of capital can disrupt the economics of the industry.

For a few years, that’s exactly what happened.

Blitzscaling

In Convoy’s earliest years, it used venture capital that it raised to “buy market share.” It offered shippers that agreed to be early adopters rates that were cheaper than market — discounted significantly compared to the rates of incumbent players.

This worked; some would say too well. Convoy was able to scale quickly and garnered significant market share from some major shippers along the way.

At first, Convoy offered shippers aggressive discounts on their major lanes and then used that wedge to get access to lower-volume lanes. This allowed the company to expand its margins in secondary lanes, offsetting losses in the primary lanes.

The growth story was impressive and investors became excited about the potential of how big Convoy could become. After all, if this story could play out with more shippers, the company would eventually become a massive multibillion dollar firm — perhaps the biggest logistics firm on the planet.

Early on, the company focused on blitzscaling — a term coined by Reid Hoffman — which means to prioritize growth at all costs. After all, Hoffman was one of Convoy’s first board members and likely set the tone of its operating playbook.

In Hoffman’s view, “You must win first prize to survive in the internet era,” because in the internet age, markets are built on “winner-take-all” outcomes.

Hoffman coined the term after studying high-growth software and platform businesses, where the unit economics were incredibly favorable to the scale of the business. His own experience building LinkedIn and PayPal had informed these lessons.

In a series of quotes in “Blitzscaling: The Lightning-Fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Companies,” Hoffman characterizes his theories that many observers of the Convoy story will recognize:

“You don’t necessarily need to have solved your revenue model before deciding to blitzscale. In fact, a key element of blitzscaling is often the willingness of investors to fund growth before the revenue model is proven — after all, it’s pretty easy to fund growth after the revenue model is proven.

“To achieve massive success, you need to have a big new opportunity — one where the market size and gross margins intersect to create enormous potential value, and there isn’t a dominant market leader or oligopoly. A big new opportunity often arises because a technological innovation creates a new market or scrambles an existing one.

“Blitzscaling is a strategy and set of techniques for driving and managing extremely rapid growth that prioritize speed over efficiency in an environment of uncertainty. Put another way, it’s an accelerant that allows your company to grow at a furious pace that knocks the competition out of the water.”

Convoy’s management and board believed that cash burn wasn’t a concern. As long as it could grow and expand margins, future investors would bid up the company at even higher valuations. After all, it was going to blitzscale its way to market domination.

The company was founded and scaled in a period when venture capital was incredibly easy to attain and everyone wanted a piece of disruptive businesses that were displacing incumbent players. Articles that covered the company early on compared its mission to what Uber had done to the taxi industry and many believed that the opportunity for Convoy was even bigger.

Prospective investors, realizing that the company was subsidizing some of its growth through shipper discounts in the early part of the relationship, looked for a metric that they could get behind.

Traditionally, freight brokerage valuations are measured on a multiple of EBITDA. But for a company that was prioritizing blitzscaling, investing in its platform and network incentives, that wasn’t possible.

So the investors that bought into the story decided that gross revenues were a sufficient metric for underwriting. If the company could continue to scale up, margins would eventually increase.

After all, if it prioritized short-term profits, it was sacrificing growth and building out a platform that could displace the incumbent players.

Nothing but net

Freight brokerages have historically reported two revenue numbers: gross revenue and net revenue. Traditionally, it was the scale of net revenues that mattered; gross revenue was a vanity statistic that everyone bragged about but was largely ignored.

When venture capital firms (and the growth equity firms that followed) began investing in digital brokerages, the startups somehow were able to convince the investors that gross revenue was the appropriate metric for valuation. That was the first and key mistake; the VCs underwrote the businesses on gross revenues. The second mistake that investors made was treating Convoy like it was a tech company and not a logistics company.

Years ago, I asked an investor who worked for a very large growth equity firm that happened to be one of C.H. Robinson’s largest investors why he also invested in Convoy. He told me that as Convoy scaled with individual shippers, there were increased margins on the freight. Also, as Convoy increased volume on a particular lane, it drove down the purchased transportation cost.

My conversation with that investor was in September 2018, right after Convoy announced a $185 million capital investment at a $1.08 billion valuation. At the time, I wondered if Convoy benefited from the early phase of a softening freight market, when margins naturally expand for brokers.

From conversations over the past few years about Convoy, it was clearly understood by industry insiders that Convoy was valued far differently by venture capitalists than was the accepted norm for the industry.

The group bidding up Convoy’s valuation included some of the most iconic names in technology and Wall Street, including Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Marc Benioff, Henry Kravis, Google’s venture arm, Fidelity and T. Rowe Price.

When the company continued to raise capital at even higher valuations, it created a great deal of bewilderment about how the company could defy the valuation economics of a very traditional — some would say boring — industry. When challenged, defenders would mention Amazon’s or Tesla’s valuations in their early days. In the mind of investors, Convoy had the same breakout potential.

All of this created a high level of resentment from industry incumbents. But for the investors, Convoy offered a chance to build a business in one of the largest and most fragmented industries on the planet: the North American trucking industry.

The company ended up raising two more rounds of financing. In November 2019, it raised $400 million at a valuation of $2.75 billion, and in April 2022, it raised an additional $410 million at a valuation of $3.8 billion.

In addition to raising capital from investors, Convoy also raised debt from banks and financial firms that the company leveraged to achieve even faster growth.

The company seemed unstoppable.

So what happened?

Over the past few days, I’ve tried to reconstruct the events that led to the sudden shutdown of Convoy. I’ve spoken with insiders at the company to try to understand how the rocket ship could suddenly run out of fuel and crash back to earth.

According to insiders, in late 2021, Convoy stopped offering incentives to shippers to join its platform. The company recognized that investors were getting weary of the incentives that drove early growth and expected to see expanding margins at increased levels of scale.

For the past two years, Convoy had higher-than-market gross margins.

In 2022, the company had 17.7% gross margins and year-to-date had 18.1% gross margins. It wasn’t easy for the company to achieve these levels and it required the firm to back away from the practices that provided early growth.

In fact, Convoy walked away from shippers and blanked on many bids when they required margin sacrifice. Industry veterans will recognize that this sounds like Convoy had become a “real logistics company” with discipline in its bidding process and that would be correct.

The problem was that sacrificing load volumes also came at the cost of hypergrowth. The company assumed that the high levels of sustained margin would be more attractive to future investors, but that wouldn’t be enough. After all, part of the growth story was now gone.

Convoy had a very sophisticated data science model and compared its buy-and-sell rates against industry benchmarks. The company was consistently buying below the averages and had locked in higher rates on contracts when rates were much higher. It was marginally profitable on the major long-haul lanes, but made far greater profits on the regional and short-haul lanes, with high win rates.

According to the insiders, the company was able to achieve this because it had a strong data science and engineering team.

But that is also partially to blame for its ultimate demise.

A very large percentage of Convoy’s budget was allocated to technology engineering and data science. The amount was far greater than would be typical of a company of its size. Additionally, when capacity was super tight during COVID, Convoy went forward with a plan to lease approximately 4,000 trailers that were a part of its drop-and-hook program.

In early 2022, everything seemed to be going right for Convoy.

Although the freight market was entering a recession, few expected a significant deterioration in the freight economy. Convoy completed a capital raise and had just completed a fully built-out version of its platform, which offered fully digital brokerage.

According to internal data, the company’s platform achieved 98% automated load matching of all loads (true pricing, negotiation and matching in the open marketplace) via its mobile or web apps and 99% for local/city loads. Drivers used the Convoy app for every step of the job 96% of the time and on-time performance was 94% (within 30 minutes of appointment).

Convoy’s executive team believed the slowdown in freight would be short-lived. If the freight recession of 2019 was any guide, it would be a slowdown lasting for a quarter or two and then the market would revert back to the mean.

Plus, market volatility might be a good thing.

After all, for the past decade, each time the market was volatile, freight brokerages were able to expand market share and could optimize their margins during periods of instability.

Although the company’s very large investment in data science and engineering was high, it was instrumental in the company’s operating and product plans. Management was reluctant to take corrective actions, even though they acknowledged the high operating expenditures and fixed costs were a significant drag on the cash position. They believed that growth would present itself when things bounced back.

They also wanted to maintain margin discipline, so the company lost freight volumes from existing customers.

As the freight market continued to deteriorate throughout 2022 and into 2023, reality started to set in. Convoy conducted a series of layoffs, which reduced the operational support teams and an Atlanta brokerage office was closed.

The trailer program, which had been an early success, had become a significant cash drain by the second quarter of 2023. The daily cost of the trailers, when considering equipment, insurance and maintenance, became an anchor around Convoy’s profit/loss metrics.

Things continued to deteriorate. The freight market had not only entered one of the worst recessions in history, this freight recession was unlike any other in history.

Gross revenues dropped from $800 million in 2021 to a run-rate of $500 million in 2023. The Convoy hypergrowth story was over.

Investors, taking direction from public markets, started to sour on non-profitable businesses. Once ignored, unit economics became of utmost importance. Even though Convoy had demonstrated its model was able to achieve margins that were much higher than typical freight brokerages, it wasn’t enough.

Investors, who had previously been unaware or ignored the realities of freight markets, suddenly realized that freight markets were among the most volatile on the planet and that freight is a commodity — and thus capacity is fungible. After all, shippers could easily find alternatives to Convoy’s services with thousands of other freight brokers in the market.

The discounts and incentives that Convoy had offered in its earliest days to achieve scale didn’t guarantee shippers would stay loyal to Convoy when the market dynamics changed.

The blitzscaling model was broken.

It may have worked fine in times of a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP), but those days also were over.

Convoy was a victim of two realities: a failure to control its own destiny by relying on investors for funding and the violence and realities of the freight market, which are outside of anyone’s control.

Broken valuation models

One assumption that almost everyone in the industry had is that Convoy had achieved enough scale that it would be impossible to kill it. After all, even if Convoy’s business model failed, someone would want to acquire it for the hundreds of millions in freight across the platform.

Silicon Valley insiders used to say that Convoy had achieved “escape velocity,” or the idea that the momentum of the business was so great that market gravity wouldn’t hold the company back.

But the business had raised too much money at valuations that defied reality.

There was a huge delta between how the VCs were bidding up digital brokerage valuations and how industry incumbents (or acquirers) looked at valuations.

Venture capital firms plan to eventually sell the businesses they invest in after the company has become very valuable. In order for VC firms that invested in Convoy to get a return, the company’s net revenues would eventually need to be of sufficient scale to overcome the operating expenses of the company, thus generating EBITDA.

After all, mature freight brokerages always sell for a multiple of EBITDA.

This meant that Convoy, the highest-profile venture-backed digital brokerage, always had a difficult task: to quickly scale the business to generate enough EBITDA to match its valuation using traditional norms. Otherwise, there would be a massive valuation reset down the line.

Convoy’s overfunding ultimately killed the business

Investors had greatly exaggerated Convoy’s valuation in their models and assumed the company was unstoppable, therefore, dooming the company by eliminating the option for a soft landing (death by overvaluation).

Here is the math. At Convoy’s last round of funding, the company was valued at $3.8 billion. It was generating $800 million in gross revenue. At 17% margins, that would equate to $136 million in net revenues.

All of the operating expenses are below this line.

Mature brokers sell on EBITDA, but there have been a number of high-growth, mid-stage brokers that have been acquired for net revenues. These firms have sold in the range of two to three times net revenues, which implies that Convoy should have been valued at around $272 million-$400 million at the time of its last funding. It was valued at 10 times more than it should have been.

When the freight market collapsed, the company had raised so much equity, but it also borrowed money from banks and other financial institutions, taking on a large amount of debt, including a $150 million line of credit from JPMorgan and $100 million in venture debt from Hercules Capital — that there was little flexibility in its capital structure to find alternatives.

The deterioration of Convoy’s revenues also meant that any metric used to value the company would require a significant rerating. In other words, a growth multiple isn’t possible.

The board had little incentive to provide bridge funding in order to get the company acquired for 1/20th of the valuation — or worse — of the valuation of its last round. After all, the investors behind the company had bought into a version of the Convoy story that appeared highly unlikely.

Additionally, the debt holders, traditionally more risk-averse, had zero incentive to fight to protect the company’s equity but wanted to avoid the company running completely out of cash.

After all, bankruptcy can be expensive.

That is why lenders have debt covenants in their deal structures — to ensure that in the event of a default the company’s assets can survive long enough to allow for a liquidation and wind-down.

In technology firms, this means that the servers must stay on long enough for prospective buyers to get a chance to conduct their due diligence and manage a transition of the tech stack to a new platform.

In recent days, with Convoy out of compliance with its loan covenants, the company’s lenders called in the note, instituting the wind-down process. It was sudden and unexpected for nearly everyone associated with the company.

Insiders tell me that the executive team had worked diligently for the past few months to find a buyer but ultimately ran out of options.

Industry incumbents have resented Convoy since its founding because of its ability to secure funding at unsustainable valuations, but that proved to be what ultimately killed the company.

Convoy’s story, while tragic for investors and insiders, should prove cautionary for other founders. Raising money at valuations that are well beyond market norms is appealing, but if growth slows and you’ve burned through the capital, early investors may lose their appetite for future investment.

In fairness to Convoy, it is not the only venture-backed digital brokerage to face this reality. There will be more failures in the freight tech space over the next few quarters.

Excess capital is rocket fuel in the early stages of growth and can provide a false sense of security, as it doesn’t force founders to build companies with traditional constraints. That is what happened with Convoy. Management didn’t respond fast enough to changing market conditions when aggressive cost-cutting was necessary. They also had a false sense of security that future investors or an acquirer would provide the ultimate backstop, neither of which happened.

As Convoy’s founders learned, there is such a thing as death by overfunding.

Uncategorized

Shipping company files surprise Chapter 7 bankruptcy, liquidation

While demand for trucking has increased, so have costs and competition, which have forced a number of players to close.

The U.S. economy is built on trucks.

As a nation we have relatively limited train assets, and while in recent years planes have played an expanded role in moving goods, trucks still represent the backbone of how everything — food, gasoline, commodities, and pretty much anything else — moves around the country.

Related: Fast-food chain closes more stores after Chapter 11 bankruptcy

"Trucks moved 61.1% of the tonnage and 64.9% of the value of these shipments. The average shipment by truck was 63 miles compared to an average of 640 miles by rail," according to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics 2023 numbers.

But running a trucking company has been tricky because the largest players have economies of scale that smaller operators don't. That puts any trucking company that's not a massive player very sensitive to increases in gas prices or drops in freight rates.

And that in turn has led a number of trucking companies, including Yellow Freight, the third-largest less-than-truckload operator; J.J. & Sons Logistics, Meadow Lark, and Boateng Logistics, to close while freight brokerage Convoy shut down in October.

Aside from Convoy, none of these brands are household names. but with the demand for trucking increasing, every company that goes out of business puts more pressure on those that remain, which contributes to increased prices.

Image source: Shutterstock

Another freight company closes and plans to liquidate

Not every bankruptcy filing explains why a company has gone out of business. In the trucking industry, multiple recent Chapter 7 bankruptcies have been tied to lawsuits that pushed otherwise successful companies into insolvency.

In the case of TBL Logistics, a Virginia-based national freight company, its Feb. 29 bankruptcy filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Virginia appears to be death by too much debt.

"In its filing, TBL Logistics listed its assets and liabilities as between $1 million and $10 million. The company stated that it has up to 49 creditors and maintains that no funds will be available for unsecured creditors once it pays administrative fees," Freightwaves reported.

The company's owners, Christopher and Melinda Bradner, did not respond to the website's request for comment.

Before it closed, TBL Logistics specialized in refrigerated and oversized loads. The company described its business on its website.

"TBL Logistics is a non-asset-based third-party logistics freight broker company providing reliable and efficient transportation solutions, management, and storage for businesses of all sizes. With our extensive network of carriers and industry expertise, we streamline the shipping process, ensuring your goods reach their destination safely and on time."

The world has a truck-driver shortage

The covid pandemic forced companies to consider their supply chain in ways they never had to before. Increased demand showed the weakness in the trucking industry and drew attention to how difficult life for truck drivers can be.

That was an issue HBO's John Oliver highlighted on his "Last Week Tonight" show in October 2022. In the episode, the host suggested that the U.S. would basically start to starve if the trucking industry shut down for three days.

"Sorry, three days, every produce department in America would go from a fully stocked market to an all-you-can-eat raccoon buffet," he said. "So it’s no wonder trucking’s a huge industry, with more than 3.5 million people in America working as drivers, from port truckers who bring goods off ships to railyards and warehouses, to long-haul truckers who move them across the country, to 'last-mile' drivers, who take care of local delivery."

The show highlighted how many truck drivers face low pay, difficult working conditions and, in many cases, crushing debt.

"Hundreds of thousands of people become truck drivers every year. But hundreds of thousands also quit. Job turnover for truckers averages over 100%, and at some companies it’s as high as 300%, meaning they’re hiring three people for a single job over the course of a year. And when a field this important has a level of job satisfaction that low, it sure seems like there’s a huge problem," Oliver shared.

The truck-driver shortage is not just a U.S. problem; it's a global issue, according to IRU.org.

"IRU’s 2023 driver shortage report has found that over three million truck driver jobs are unfilled, or 7% of total positions, in 36 countries studied," the global transportation trade association reported.

"With the huge gap between young and old drivers growing, it will get much worse over the next five years without significant action."

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

bankruptcy bankruptcies pandemic stocks commoditiesUncategorized

Wendy’s has a new deal for daylight savings time haters

The Daylight Savings Time promotion slashes prices on breakfast.

Daylight Savings Time, or the practice of advancing clocks an hour in the spring to maximize natural daylight, is a controversial practice because of the way it leaves many feeling off-sync and tired on the second Sunday in March when the change is made and one has one less hour to sleep in.

Despite annual "Abolish Daylight Savings Time" think pieces and online arguments that crop up with unwavering regularity, Daylight Savings in North America begins on March 10 this year.

Related: Coca-Cola has a new soda for Diet Coke fans

Tapping into some people's very vocal dislike of Daylight Savings Time, fast-food chain Wendy's (WEN) is launching a daylight savings promotion that is jokingly designed to make losing an hour of sleep less painful and encourage fans to order breakfast anyway.

Image source: Wendy's.

Promotion wants you to compensate for lost sleep with cheaper breakfast

As it is also meant to drive traffic to the Wendy's app, the promotion allows anyone who makes a purchase of $3 or more through the platform to get a free hot coffee, cold coffee or Frosty Cream Cold Brew.

More Food + Dining:

- Taco Bell menu tries new take on an American classic

- McDonald's menu goes big, brings back fan favorites (with a catch)

- The 10 best food stocks to buy now

Available during the Wendy's breakfast hours of 6 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. (which, naturally, will feel even earlier due to Daylight Savings), the deal also allows customers to buy any of its breakfast sandwiches for $3. Items like the Sausage, Egg and Cheese Biscuit, Breakfast Baconator and Maple Bacon Chicken Croissant normally range in price between $4.50 and $7.

The choice of the latter is quite wide since, in the years following the pandemic, Wendy's has made a concerted effort to expand its breakfast menu with a range of new sandwiches with egg in them and sweet items such as the French Toast Sticks. The goal was both to stand out from competitors with a wider breakfast menu and increase traffic to its stores during early-morning hours.

Wendy's deal comes after controversy over 'dynamic pricing'

But last month, the chain known for the square shape of its burger patties ignited controversy after saying that it wanted to introduce "dynamic pricing" in which the cost of many of the items on its menu will vary depending on the time of day. In an earnings call, chief executive Kirk Tanner said that electronic billboards would allow restaurants to display various deals and promotions during slower times in the early morning and late at night.

Outcry was swift and Wendy's ended up walking back its plans with words that they were "misconstrued" as an intent to surge prices during its most popular periods.

While the company issued a statement saying that any changes were meant as "discounts and value offers" during quiet periods rather than raised prices during busy ones, the reputational damage was already done since many saw the clarification as another way to obfuscate its pricing model.

"We said these menuboards would give us more flexibility to change the display of featured items," Wendy's said in its statement. "This was misconstrued in some media reports as an intent to raise prices when demand is highest at our restaurants."

The Daylight Savings Time promotion, in turn, is also a way to demonstrate the kinds of deals Wendy's wants to promote in its stores without putting up full-sized advertising or posters for what is only relevant for a few days.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemicUncategorized

Comments on February Employment Report

The headline jobs number in the February employment report was above expectations; however, December and January payrolls were revised down by 167,000 combined. The participation rate was unchanged, the employment population ratio decreased, and the …

Prime (25 to 54 Years Old) Participation

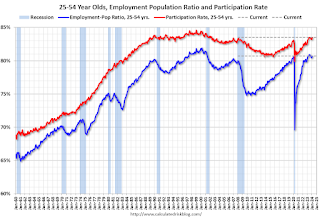

Since the overall participation rate is impacted by both cyclical (recession) and demographic (aging population, younger people staying in school) reasons, here is the employment-population ratio for the key working age group: 25 to 54 years old.

The 25 to 54 years old participation rate increased in February to 83.5% from 83.3% in January, and the 25 to 54 employment population ratio increased to 80.7% from 80.6% the previous month.

Average Hourly Wages

The graph shows the nominal year-over-year change in "Average Hourly Earnings" for all private employees from the Current Employment Statistics (CES).

The graph shows the nominal year-over-year change in "Average Hourly Earnings" for all private employees from the Current Employment Statistics (CES). Wage growth has trended down after peaking at 5.9% YoY in March 2022 and was at 4.3% YoY in February.

Part Time for Economic Reasons

From the BLS report:

From the BLS report:"The number of people employed part time for economic reasons, at 4.4 million, changed little in February. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs."The number of persons working part time for economic reasons decreased in February to 4.36 million from 4.42 million in February. This is slightly above pre-pandemic levels.

These workers are included in the alternate measure of labor underutilization (U-6) that increased to 7.3% from 7.2% in the previous month. This is down from the record high in April 2020 of 23.0% and up from the lowest level on record (seasonally adjusted) in December 2022 (6.5%). (This series started in 1994). This measure is above the 7.0% level in February 2020 (pre-pandemic).

Unemployed over 26 Weeks

This graph shows the number of workers unemployed for 27 weeks or more.

This graph shows the number of workers unemployed for 27 weeks or more. According to the BLS, there are 1.203 million workers who have been unemployed for more than 26 weeks and still want a job, down from 1.277 million the previous month.

This is close to pre-pandemic levels.

Job Streak

| Headline Jobs, Top 10 Streaks | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year Ended | Streak, Months | |

| 1 | 2019 | 100 |

| 2 | 1990 | 48 |

| 3 | 2007 | 46 |

| 4 | 1979 | 45 |

| 5 | 20241 | 38 |

| 6 tie | 1943 | 33 |

| 6 tie | 1986 | 33 |

| 6 tie | 2000 | 33 |

| 9 | 1967 | 29 |

| 10 | 1995 | 25 |

| 1Currrent Streak | ||

Summary:

The headline monthly jobs number was above consensus expectations; however, December and January payrolls were revised down by 167,000 combined. The participation rate was unchanged, the employment population ratio decreased, and the unemployment rate was increased to 3.9%. Another solid report.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 hours ago

International2 hours agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Government1 month ago

Government1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex