International

Crying Wolf on (Hyper)Inflation?

[This article is part of the Understanding Money Mechanics series, by Robert P. Murphy. The series will be published as a book in 2021.]

In chapter 10 we explained the connection between monetary inflation and price inflation, and warned that there…

[This article is part of the Understanding Money Mechanics series, by Robert P. Murphy. The series will be published as a book in 2021.]

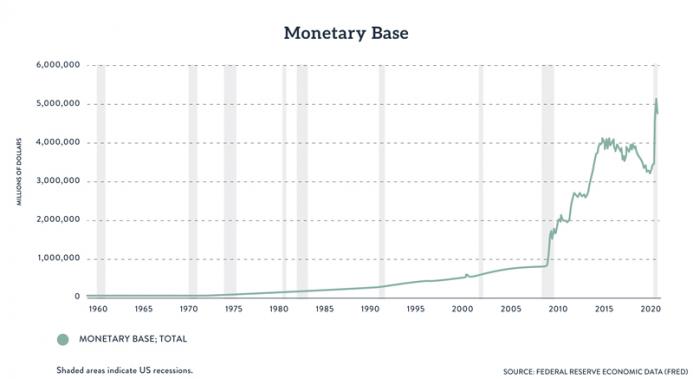

In chapter 10 we explained the connection between monetary inflation and price inflation, and warned that there is no simple one-to-one relationship. This fact has been very relevant in the wake of the various rounds of quantitative easing (QE) that the Federal Reserve implemented after the financial crisis of 2008. The following chart shows the huge increase in the monetary base since 2008:

In the early years of QE, many economists—including the present author1—warned that the Fed’s unprecedented monetary inflation would cause a significant increase in consumer prices. Some pundits went so far as to warn of actual hyperinflation, reminding Americans of the terrible experiences of Weimar Germany and modern Zimbabwe. Yet years passed by without the “inflation time bomb” exploding. This led the proponents of the Fed’s policies to mock the warnings as crying wolf. In this chapter, we’ll assess several popular explanations for why the Fed’s monetary inflation since 2008 hasn’t generated a comparable increase in price inflation. Because this book is intended to be educational rather than polemical, we will merely mention some of the pros and cons for each possibility, rather than arguing which are correct and which should be rejected.“The government’s CPI measure vastly understates price inflation.”

The benefit of this type of explanation is that it focuses proper cynicism on data produced by government agencies, which are not renowned for their unwavering devotion to truth.

However, the problem with this explanation is that many critics of QE were warning of significant price inflation that could not have been hidden through statistical tricks. Americans were able to fill up their vehicles in 2010 (say) and for most drivers the price was $3 or less per gallon of gasoline. If some of the more serious warnings of price inflation had proved correct, this would not have been possible.

Keep in mind that the official government measures showed twelve-month CPI (Consumer Price Index) inflation hit a whopping 14.6 percent in March 1980. Had the government told Americans at that time that inflation were under 2 percent, it would have been an obvious lie. So although the conventional measures may be significantly understating the rising cost of living since 2008, the mismatch between the extreme warnings and reality can’t be explained entirely by reference to data fudging.

“Inflation won’t be a problem while we still suffer from an output gap / idle resources.”

According to both Keynesians and proponents of MMT (modern monetary theory), increased government spending—even if financed by monetary inflation—won’t generate large increases in consumer prices so long as the economy is operating below its capacity. In more technical terms, they argue that so long as real GDP is below potential GDP, increases in nominal spending serve to boost real output rather than prices. The intuitive idea is that the unemployed and other idle resources will absorb new spending first, before tightening labor and resource markets cause wages and other prices to begin rising.

On the plus side, the Keynesians and MMT camp were correct when they said the various rounds of QE since 2008 would not cause extreme price inflation, let alone hyperinflation. Since some of their opponents did predict such a result, the Keynesians and MMTers can understandably claim vindication.

However, there are numerous problems with this explanation. For one thing, the Keynesians didn’t merely predict a lack of significant price inflation; many of them predicted price deflation. For example, Paul Krugman in a blog post in early 2010 posted a graph of collapsing CPI inflation, warned that the disinflation could soon turn to outright deflation, and ended with, “Japan, here we come.”2 (Japan had experienced sustained reductions in CPI.)

Five months later, Krugman admitted that the standard Keynesian tool of the Phillips curve—which models a tradeoff, at least in the short run, between unemployment and (price) inflation—hadn’t worked so well in the aftermath of the financial crisis. As Krugman acknowledged in a post entitled, “The Mysteries of Deflation (Wonkish),” coming into the Great Recession, “the inflation-adjusted Phillips curve predict[ed] not just deflation, but accelerating deflation in the face of a really prolonged economic slump” (italics in original).3 And since that hadn’t happened, the Keynesians too had to tinker with their model in light of reality. To generalize, in 2009 the conservative economists had predicted accelerating inflation, while the progressive economists had predicted accelerating deflation.

Another serious problem with the no-inflation-until-full-employment doctrine is that it was disproved in the so-called stagflation of the 1970s. The Keynesian mindset of the postwar era had originally led policymakers to believe that they had to choose between either high unemployment or high inflation in consumer prices. It should not have been possible for the economy to suffer through both evils at the same time.

And yet, once Richard Nixon killed the last vestiges of the gold standard in 1971 (which we explained in chapter 3), the remainder of the decade saw unusually high levels of both. For example, in May 1975 the unemployment rate was 9 percent while the twelve-month change in CPI was 9.3 percent. In light of the US experience of the 1970s, simple rules such as “the economy can’t overheat while there are still idle resources” can’t be the full story.

“Yes, the money supply increased dramatically after mid-2008, but the demand to hold it increased as well.”

On the plus side, this explanation is necessarily correct; every fact about prices can be handled in a supply-and-demand framework. The “price” of money refers to its purchasing power; how many units of goods and services can a unit of money fetch on the market? If we hold the demand for money constant and vastly increase its supply (through rounds of QE, for example), then the “price of money” falls, meaning the currency becomes weaker, meaning that the prices of goods and services quoted in that money go up. This is of course just another way of describing price inflation.

However, in practice other things might not remain equal; the demand for money might increase too, especially during a financial crisis. Remember that the “demand to hold money” isn’t the same thing as a desire for more wealth. If someone has (say) $100,000 in liquid wealth, it will generally be diversified among several assets, including stocks, bonds, precious metals, life insurance, cryptocurrencies, and some in actual money (whether literal cash on hand or money on deposit in a checking account). During times of great uncertainty, the advantages of holding actual money become more important to many people, and so they adjust their portfolios to hold a greater share of their wealth in the form of money. This is what it means to say the “demand to hold money” increases.

After the fact, because we didn’t observe an unusual drop in the purchasing power of the US dollar from 2008 onward, we can confidently say that the demand to hold US dollars increased to offset the increase in US dollars orchestrated by the Federal Reserve. This is necessarily true.

However, the downside of this explanation is that we can only be sure to apply it correctly in hindsight. If we want to assess what will happen to the path of price inflation in the future, we need to forecast changes on both the supply and demand sides, and of course we might be wrong about our forecasts. This becomes especially problematic if changes in the supply of money directly cause an increase in the demand to hold it, a possibility we discuss in the next section.

“Of course QE wasn’t inflationary. Since the economy was stuck in a liquidity trap, the Fed’s bond purchases were just an asset swap.”

As we explain in chapters 7 and 15, Keynesian economists argued that once the Fed had slashed nominal interest rates to zero in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the US economy was in a “liquidity trap,” where conventional monetary policy no longer had traction. At this point, so the story went, the Fed had to switch to so-called quantitative easing, where the emphasis was on the size of the central bank’s asset purchases (rather than its target for the relevant interest rate). In the Keynesian view, the relative impotence of monetary policy during a liquidity trap was the justification for government budget deficits (i.e., fiscal policy) as a means of boosting aggregate demand.

One offshoot of this typical Keynesian framework was the argument that the Fed’s purchase of Treasury securities looked like a mere asset swap. (It should be noted that Chicago school economist and Nobel laureate Eugene Fama also made this argument, not just Keynesians.4) It was true that the Fed’s bond purchases “created money out of thin air” and injected it into the economy, as the critics warned. But in so doing, the Fed took government debt securities out of the economy as well. And to the extent that US Treasury securities earning (close to) 0 percent are similar to bank reserves parked at the Fed (which also earned close to 0 percent), the inflationary impact of the QE programs was significantly muted. A $10 billion purchase injected $10 billion of base money into the financial sector, but it simultaneously removed $10 billion of “near money.”

The benefit of this explanation is that it is an important caveat to a naïve supply-and-demand analysis; it would be foolish to focus merely on increases in the supply of money if the very process that created the money also boosted the demand for cash (by removing “near money” substitutes dollar for dollar).

The downside of this analysis is that it ignores the influence central bank policy has on asset prices. For an exaggerated example, suppose the Federal Reserve announced a new plan of buying any model year 2010 Ford pickup truck for $100,000. This announcement would immediately cause the “market price” of such trucks to jump to $100,000. At the moment of sale, the Fed would be engaged in a mere asset swap; it would provide $100,000 in new bank reserves in exchange for a truck valued at $100,000. Yet, clearly, our hypothetical truck-buying program would distort the used vehicle market and would financially benefit the lucky owners of 2010 Ford trucks. In the same way, even though at the moment of purchasing Treasury bonds the Fed is engaging in an asset swap, the “market” price of those Treasury bonds might be propped up by the Fed’s purchase itself.

“The Fed’s new policy of paying interest on reserves arrested the usual money multiplier.”

As we explained in chapter 7, in October 2008 the Fed implemented a new policy of paying interest on bank reserves parked at the Fed. From an individual commercial bank’s perspective, the interest payment offered an incentive to refrain from making new loans to customers. Because of the massive QE purchases, plenty of newly created bank reserves flooded the system. Yet even though commercial banks had the legal ability to pyramid trillions of dollars of newly created loans on top of the Fed’s injections, they largely remained on the sidelines. The following chart of “excess” bank reserves illustrates this unprecedented development:

As the chart indicates, prior to the financial crisis it was typical for the banking system as a whole to be (nearly) “fully loaned up,” meaning that excess reserves were close to $0. In other words, the normal state of affairs—prior to 2008—was for banks to make loans to their own customers until the point at which all of their reserves were “required reserves,” meaning that they legally couldn’t lend more money and still satisfy their reserves requirements.Yet after 2008, as the Fed injected new reserves into the system through its three rounds of QE, the commercial banks did not lend out (several multiples of) these new reserves, as a standard textbook treatment would suggest. As the chart shows, at the (local) peak in mid-2014, excess reserves were just shy of $2.7 trillion. Could the policy of paying interest on reserves, begun in October 2008, explain this pattern?

The introduction of interest payments was indeed an important innovation in Fed policy, giving the central bank a means of divorcing its open market operations from interest rate targets. (For example, when the Fed began raising its policy interest rate in late 2015, its balance sheet remained constant for about two years thereafter. The Fed steadily raised rates during this period by hiking the interest rate paid on reserves, not by selling off Fed assets.) When trying to understand commercial bank loan activity from late 2008 onward, the Fed’s new policy is definitely an important consideration.

However, when answering the question, “Why didn’t the Fed’s QE programs cause significant consumer price inflation?” the new policy of interest on reserves seems inadequate to bear the full weight of the explanation. After bouncing around (but never rising above 1.15 percent) in the first few months after its introduction, the interest rate paid on excess reserves settled at 0.25 percent by mid-December 2008. It stayed at that near-zero level for a full seven years, being raised to 0.50 percent in mid-December 2015.

It seems unlikely that a mere twenty-five basis points can explain why nearly $2.7 trillion in excess reserves piled up in the banking system rather than being funneled into new loans. Presumably, even without the extra inducement of a guaranteed 0.25 percent, commercial banks would have kept most of their new reserves safely parked at the Fed from 2008 through 2015.

“The new money stayed bottled up in the banks; it never got out into the hands of the public.”

Whether tied to the Fed’s policy of paying interest on reserves, a common explanation for the lack of significant consumer price inflation is that the newly injected money never got into the hands of the general public.

The benefit of this insight is that it correctly takes note of the huge increase in excess reserves (shown in the chart above). Yet it fails to account for the fact that M1, which includes currency held by the public as well as checking account balances, did begin a rapid increase in the wake of the financial crisis:NOTE: the above chart was created before the Fed in February 2021 changed its M1 money stock series retroactively back to May 2020. (For details see the discussion in chapter 8.) In particular, the spike shown in the spring of 2020 existed even with the original definition of M1; it shows an actual increase in money held by the public, and is not an artifact of the Fed’s 2021 statistical revision.

As the chart shows, the M1 money stock was virtually flat from early 2005 through early 2008. Yet it began steadily rising from late 2008 onward (and of course spiked dramatically during the coronavirus panic in 2020). We can’t explain the lack of high CPI inflation by claiming there was no new money held by the public, because this simply isn’t true.

“The new money went into the stock market, real estate, and commodities, not into retail goods.”

The benefit of this type of explanation is that it underscores the arbitrariness of the conventional public discussions about money and prices. Why should the particular metric of the Consumer Price Index, as tabulated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics with its controversial techniques of “hedonic” adjustments, be the default measure of “inflation”? Indeed, academic economists have long argued that on a theoretical level, rising asset prices can be indicative of “easy money” just as surely as rising consumer prices.5 For an obvious example, rising home prices are relevant to “the cost of shelter” along with real estate rental prices, even though only the latter are currently included in the CPI.

The danger in this type of explanation is that it often misconstrues what actually happens when new money is injected into the economy. In reality, it is not the case that some money is “in” the stock market, while other portions of the money stock are “in” consumer goods. At any given time, all units of physical currency are held in cash balances, located in people’s wallets (or home safes), or inside of commercial bank vaults. If someone buys one hundred shares of a stock at $10 per share, it’s not that money “goes into the stock market.” Rather, what typically happens is that $1,000 is debited from the checking account of the buyer, while an equal amount is credited to the checking account of the seller. If the buyer and seller are clients of different banks, their transaction might cause some reserves to transfer from one bank to the other, but nobody looking at the money after the fact would be able to tell that it “had gone into the stock market.”

“Those warning of significant price inflation will eventually be proven right.”

During the housing bubble years in the early and mid-2000s, a growing number of alarmists warned that home prices were rising to absurd levels and that Americans should prepare for a giant crash in real estate and stocks. While the bubble was still inflating, the conventional wisdom dismissed these warnings as baseless fearmongering. It was only after the crash that most people recognized that the doomsayers had been correct.

Likewise, it is possible that the US dollar will crash against other currencies, interest rates on US Treasurys will spike, and official CPI inflation will rise well above the Fed’s target of 2 percent. If this happens, those early critics of the Fed’s QE policies could plausibly claim, “We were right about the impact, just not about the timing.”

On the downside, the problem with this explanation is that most of those warning of significant price inflation led their audiences to believe that it would be hitting within a few years at the latest. If they had coupled their initial warnings with the caveat “CPI inflation won’t be a problem for a decade but then it will get out of hand,” the reaction to their analyses would have been different.

- 1. Specifically, the present author lost public wagers to (free market) economists David R. Henderson and Bryan Caplan on whether twelve-month CPI increases would exceed 10 percent by January 2013 and January 2016, respectively. For a discussion from various economists on why their price inflation predictions turned out right or wrong, see Brian Doherty, Peter Schiff, David R. Henderson, Scott Sumner, and Robert Murphy, “Whatever Happened to Inflation?,” Reason, December 2014, https://reason.com/2014/11/30/whatever-happened-to-inflation/.

- 2. Paul Krugman, “Core Logic,” Paul Krugman blogs, New York Times, Feb. 26, 2010, https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/02/26/core-logic/.

- 3. Paul Krugman, “The Mysteries of Deflation (Wonkish),” Paul Krugman blogs, New York Times, July 26, 2010, https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/26/mysteries-of-deflation-wonkish/.

- 4. The entire debate lies outside the scope of the present book, but readers should be aware that some prominent Keynesians—in particular Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong—changed sides on this issue. See Scott Sumner, “Brad Delong, Sounding Unusually Market Monetarist, Calls a Nobel Prize-Winning Believer in Liquidity Traps a ‘Dumbass,’” Money Illusion (blog), October 30, 2013, https://www.themoneyillusion.com/brad-delong-sounding-unusually-market-monetarist-calls-a-nobel-prize-winning-believer-in-liquidity-traps-a-dumbass/.

- 5. The classic paper is Armen Alchian and Benjamin Klein, “On a Correct Measure of Inflation,” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 5, no. 1 (February 1973): 173–91. For a nontechnical summary, see Robert P. Murphy, “Fed Policy and Asset Prices,” Mises Daily, Oct. 26, 2011, https://mises.org/library/fed-policy-and-asset-prices.

International

United Airlines adds new flights to faraway destinations

The airline said that it has been working hard to "find hidden gem destinations."

Since countries started opening up after the pandemic in 2021 and 2022, airlines have been seeing demand soar not just for major global cities and popular routes but also for farther-away destinations.

Numerous reports, including a recent TripAdvisor survey of trending destinations, showed that there has been a rise in U.S. traveler interest in Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea and Vietnam as well as growing tourism traction in off-the-beaten-path European countries such as Slovenia, Estonia and Montenegro.

Related: 'No more flying for you': Travel agency sounds alarm over risk of 'carbon passports'

As a result, airlines have been looking at their networks to include more faraway destinations as well as smaller cities that are growing increasingly popular with tourists and may not be served by their competitors.

Shutterstock

United brings back more routes, says it is committed to 'finding hidden gems'

This week, United Airlines (UAL) announced that it will be launching a new route from Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) to Morocco's Marrakesh. While it is only the country's fourth-largest city, Marrakesh is a particularly popular place for tourists to seek out the sights and experiences that many associate with the country — colorful souks, gardens with ornate architecture and mosques from the Moorish period.

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

"We have consistently been ahead of the curve in finding hidden gem destinations for our customers to explore and remain committed to providing the most unique slate of travel options for their adventures abroad," United's SVP of Global Network Planning Patrick Quayle, said in a press statement.

The new route will launch on Oct. 24 and take place three times a week on a Boeing 767-300ER (BA) plane that is equipped with 46 Polaris business class and 22 Premium Plus seats. The plane choice was a way to reach a luxury customer customer looking to start their holiday in Marrakesh in the plane.

Along with the new Morocco route, United is also launching a flight between Houston (IAH) and Colombia's Medellín on Oct. 27 as well as a route between Tokyo and Cebu in the Philippines on July 31 — the latter is known as a "fifth freedom" flight in which the airline flies to the larger hub from the mainland U.S. and then goes on to smaller Asian city popular with tourists after some travelers get off (and others get on) in Tokyo.

United's network expansion includes new 'fifth freedom' flight

In the fall of 2023, United became the first U.S. airline to fly to the Philippines with a new Manila-San Francisco flight. It has expanded its service to Asia from different U.S. cities earlier last year. Cebu has been on its radar amid growing tourist interest in the region known for marine parks, rainforests and Spanish-style architecture.

With the summer coming up, United also announced that it plans to run its current flights to Hong Kong, Seoul, and Portugal's Porto more frequently at different points of the week and reach four weekly flights between Los Angeles and Shanghai by August 29.

"This is your normal, exciting network planning team back in action," Quayle told travel website The Points Guy of the airline's plans for the new routes.

stocks pandemic south korea japan hong kong europeanInternational

Walmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

The retail superstore is adding a new feature to its Walmart+ plan — and customers will be happy.

It's just been a few days since Target (TGT) launched its new Target Circle 360 paid membership plan.

The plan offers free and fast shipping on many products to customers, initially for $49 a year and then $99 after the initial promotional signup period. It promises to be a success, since many Target customers are loyal to the brand and will go out of their way to shop at one instead of at its two larger peers, Walmart and Amazon.

Related: Walmart makes a major price cut that will delight customers

And stop us if this sounds familiar: Target will rely on its more than 2,000 stores to act as fulfillment hubs.

This model is a proven winner; Walmart also uses its more than 4,600 stores as fulfillment and shipping locations to get orders to customers as soon as possible.

Sometimes, this means shipping goods from the nearest warehouse. But if a desired product is in-store and closer to a customer, it reduces miles on the road and delivery time. It's a kind of logistical magic that makes any efficiency lover's (or retail nerd's) heart go pitter patter.

Walmart rolls out answer to Target's new membership tier

Walmart has certainly had more time than Target to develop and work out the kinks in Walmart+. It first launched the paid membership in 2020 during the height of the pandemic, when many shoppers sheltered at home but still required many staples they might ordinarily pick up at a Walmart, like cleaning supplies, personal-care products, pantry goods and, of course, toilet paper.

It also undercut Amazon (AMZN) Prime, which costs customers $139 a year for free and fast shipping (plus several other benefits including access to its streaming service, Amazon Prime Video).

Walmart+ costs $98 a year, which also gets you free and speedy delivery, plus access to a Paramount+ streaming subscription, fuel savings, and more.

If that's not enough to tempt you, however, Walmart+ just added a new benefit to its membership program, ostensibly to compete directly with something Target now has: ultrafast delivery.

Target Circle 360 particularly attracts customers with free same-day delivery for select orders over $35 and as little as one-hour delivery on select items. Target executes this through its Shipt subsidiary.

We've seen this lightning-fast delivery speed only in snippets from Amazon, the king of delivery efficiency. Who better to take on Target, though, than Walmart, which is using a similar store-as-fulfillment-center model?

"Walmart is stepping up to save our customers even more time with our latest delivery offering: Express On-Demand Early Morning Delivery," Walmart said in a statement, just a day after Target Circle 360 launched. "Starting at 6 a.m., earlier than ever before, customers can enjoy the convenience of On-Demand delivery."

Walmart (WMT) clearly sees consumers' desire for near-instant delivery, which obviously saves time and trips to the store. Rather than waiting a day for your order to show up, it might be on your doorstep when you wake up.

Consumers also tend to spend more money when they shop online, and they remain stickier as paying annual members. So, to a growing number of retail giants, almost instant gratification like this seems like something worth striving for.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic mexicoInternational

President Biden Delivers The “Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President”

President Biden Delivers The "Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President"

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through…

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through the State of The Union, President Biden can go back to his crypt now.

Whatever 'they' gave Biden, every American man, woman, and the other should be allowed to take it - though it seems the cocktail brings out 'dark Brandon'?

Tl;dw: Biden's Speech tonight ...

-

Fund Ukraine.

-

Trump is threat to democracy and America itself.

-

Abortion is good.

-

American Economy is stronger than ever.

-

Inflation wasn't Biden's fault.

-

Illegals are Americans too.

-

Republicans are responsible for the border crisis.

-

Trump is bad.

-

Biden stands with trans-children.

-

J6 was the worst insurrection since the Civil War.

(h/t @TCDMS99)

Tucker Carlson's response sums it all up perfectly:

"that was possibly the darkest, most un-American speech given by an American president. It wasn't a speech, it was a rant..."

Carlson continued: "The true measure of a nation's greatness lies within its capacity to control borders, yet Bid refuses to do it."

"In a fair election, Joe Biden cannot win"

And concluded:

“There was not a meaningful word for the entire duration about the things that actually matter to people who live here.”

Victor Davis Hanson added some excellent color, but this was probably the best line on Biden:

"he doesn't care... he lives in an alternative reality."

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 8, 2024

* * *

Watch SOTU Live here...

* * *

Mises' Connor O'Keeffe, warns: "Be on the Lookout for These Lies in Biden's State of the Union Address."

On Thursday evening, President Joe Biden is set to give his third State of the Union address. The political press has been buzzing with speculation over what the president will say. That speculation, however, is focused more on how Biden will perform, and which issues he will prioritize. Much of the speech is expected to be familiar.

The story Biden will tell about what he has done as president and where the country finds itself as a result will be the same dishonest story he's been telling since at least the summer.

He'll cite government statistics to say the economy is growing, unemployment is low, and inflation is down.

Something that has been frustrating Biden, his team, and his allies in the media is that the American people do not feel as economically well off as the official data says they are. Despite what the White House and establishment-friendly journalists say, the problem lies with the data, not the American people's ability to perceive their own well-being.

As I wrote back in January, the reason for the discrepancy is the lack of distinction made between private economic activity and government spending in the most frequently cited economic indicators. There is an important difference between the two:

-

Government, unlike any other entity in the economy, can simply take money and resources from others to spend on things and hire people. Whether or not the spending brings people value is irrelevant

-

It's the private sector that's responsible for producing goods and services that actually meet people's needs and wants. So, the private components of the economy have the most significant effect on people's economic well-being.

Recently, government spending and hiring has accounted for a larger than normal share of both economic activity and employment. This means the government is propping up these traditional measures, making the economy appear better than it actually is. Also, many of the jobs Biden and his allies take credit for creating will quickly go away once it becomes clear that consumers don't actually want whatever the government encouraged these companies to produce.

On top of all that, the administration is dealing with the consequences of their chosen inflation rhetoric.

Since its peak in the summer of 2022, the president's team has talked about inflation "coming back down," which can easily give the impression that it's prices that will eventually come back down.

But that's not what that phrase means. It would be more honest to say that price increases are slowing down.

Americans are finally waking up to the fact that the cost of living will not return to prepandemic levels, and they're not happy about it.

The president has made some clumsy attempts at damage control, such as a Super Bowl Sunday video attacking food companies for "shrinkflation"—selling smaller portions at the same price instead of simply raising prices.

In his speech Thursday, Biden is expected to play up his desire to crack down on the "corporate greed" he's blaming for high prices.

In the name of "bringing down costs for Americans," the administration wants to implement targeted price ceilings - something anyone who has taken even a single economics class could tell you does more harm than good. Biden would never place the blame for the dramatic price increases we've experienced during his term where it actually belongs—on all the government spending that he and President Donald Trump oversaw during the pandemic, funded by the creation of $6 trillion out of thin air - because that kind of spending is precisely what he hopes to kick back up in a second term.

If reelected, the president wants to "revive" parts of his so-called Build Back Better agenda, which he tried and failed to pass in his first year. That would bring a significant expansion of domestic spending. And Biden remains committed to the idea that Americans must be forced to continue funding the war in Ukraine. That's another topic Biden is expected to highlight in the State of the Union, likely accompanied by the lie that Ukraine spending is good for the American economy. It isn't.

It's not possible to predict all the ways President Biden will exaggerate, mislead, and outright lie in his speech on Thursday. But we can be sure of two things. The "state of the Union" is not as strong as Biden will say it is. And his policy ambitions risk making it much worse.

* * *

The American people will be tuning in on their smartphones, laptops, and televisions on Thursday evening to see if 'sloppy joe' 81-year-old President Joe Biden can coherently put together more than two sentences (even with a teleprompter) as he gives his third State of the Union in front of a divided Congress.

President Biden will speak on various topics to convince voters why he shouldn't be sent to a retirement home.

The state of our union under President Biden: three years of decline. pic.twitter.com/Da1KOIb3eR

— Speaker Mike Johnson (@SpeakerJohnson) March 7, 2024

According to CNN sources, here are some of the topics Biden will discuss tonight:

Economic issues: Biden and his team have been drafting a speech heavy on economic populism, aides said, with calls for higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy – an attempt to draw a sharp contrast with Republicans and their likely presidential nominee, Donald Trump.

Health care expenses: Biden will also push for lowering health care costs and discuss his efforts to go after drug manufacturers to lower the cost of prescription medications — all issues his advisers believe can help buoy what have been sagging economic approval ratings.

Israel's war with Hamas: Also looming large over Biden's primetime address is the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, which has consumed much of the president's time and attention over the past few months. The president's top national security advisers have been working around the clock to try to finalize a ceasefire-hostages release deal by Ramadan, the Muslim holy month that begins next week.

An argument for reelection: Aides view Thursday's speech as a critical opportunity for the president to tout his accomplishments in office and lay out his plans for another four years in the nation's top job. Even though viewership has declined over the years, the yearly speech reliably draws tens of millions of households.

Sources provided more color on Biden's SOTU address:

The speech is expected to be heavy on economic populism. The president will talk about raising taxes on corporations and the wealthy. He'll highlight efforts to cut costs for the American people, including pushing Congress to help make prescription drugs more affordable.

Biden will talk about the need to preserve democracy and freedom, a cornerstone of his re-election bid. That includes protecting and bolstering reproductive rights, an issue Democrats believe will energize voters in November. Biden is also expected to promote his unity agenda, a key feature of each of his addresses to Congress while in office.

Biden is also expected to give remarks on border security while the invasion of illegals has become one of the most heated topics among American voters. A majority of voters are frustrated with radical progressives in the White House facilitating the illegal migrant invasion.

It is probable that the president will attribute the failure of the Senate border bill to the Republicans, a claim many voters view as unfounded. This is because the White House has the option to issue an executive order to restore border security, yet opts not to do so

Maybe this is why?

Most Americans are still unaware that the census counts ALL people, including illegal immigrants, for deciding how many House seats each state gets!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 7, 2024

This results in Dem states getting roughly 20 more House seats, which is another strong incentive for them not to deport illegals.

While Biden addresses the nation, the Biden administration will be armed with a social media team to pump propaganda to at least 100 million Americans.

"The White House hosted about 70 creators, digital publishers, and influencers across three separate events" on Wednesday and Thursday, a White House official told CNN.

Not a very capable social media team...

The State of Confusion https://t.co/C31mHc5ABJ

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) March 7, 2024

The administration's move to ramp up social media operations comes as users on X are mostly free from government censorship with Elon Musk at the helm. This infuriates Democrats, who can no longer censor their political enemies on X.

Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers tell Axios that the president's SOTU performance will be critical as he tries to dispel voter concerns about his elderly age. The address reached as many as 27 million people in 2023.

"We are all nervous," said one House Democrat, citing concerns about the president's "ability to speak without blowing things."

The SOTU address comes as Biden's polling data is in the dumps.

BetOnline has created several money-making opportunities for gamblers tonight, such as betting on what word Biden mentions the most.

As well as...

We will update you when Tucker Carlson's live feed of SOTU is published.

Fuck it. We’ll do it live! Thursday night, March 7, our live response to Joe Biden’s State of the Union speech. pic.twitter.com/V0UwOrgKvz

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 6, 2024

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 hours ago

International3 hours agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex