Uncategorized

A record-breaking recovery for Black and Hispanic workers: Prime-age employment rates have hit an all-time high alongside tremendous wage growth

U.S. labor market strength in the recovery has been extraordinary because policymakers addressed the pandemic and subsequent recession at the scale of…

U.S. labor market strength in the recovery has been extraordinary because policymakers addressed the pandemic and subsequent recession at the scale of the problem. Unemployment has been at or below 4.0% for 27 months running, the longest such stretch since the late 1960s. Low-wage workers experienced an unprecedented surge in wage growth over the last four years, as shown in our new report.

These historically robust outcomes extended to Black and Hispanic workers. In 2023, the share of Black and Hispanic people ages 25-54 with a job hit an all-time high. Further, real wage growth among Black and Hispanic workers experienced a significant turnaround from the stagnant wage growth they suffered in much of the prior four decades.

Record-breaking employment-to-population ratio

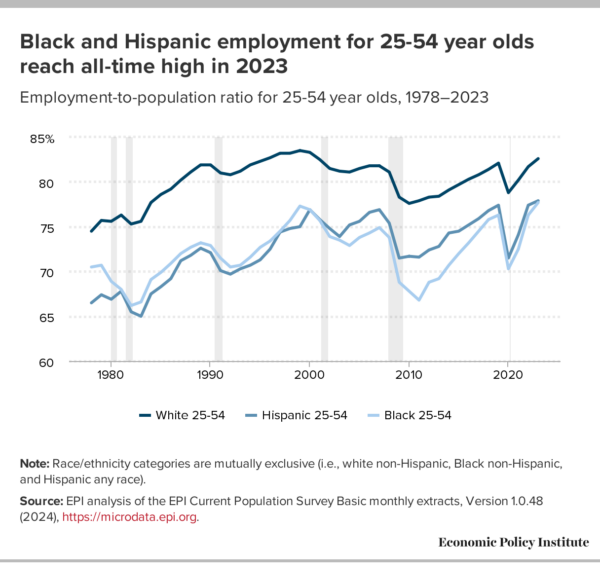

The share of the population ages 25-54 with a job—the prime-age employment-to-population ratio (PA EPOP)—rose to 80.7% in 2023, surpassing the pre-pandemic high of 80.0% in 2019 and marking the highest level since 2000. Historically marginalized workers are hit harder than other workers in recessions. In tight labor markets like today’s, historically marginalized workers experience more improved labor market outcomes and faster wage growth. In fact, Black and Hispanic workers hit all-time high employment rates in 2023: The Black PA EPOP hit 77.7% in 2023, better than its previous high in 1999 (77.3%). The Hispanic PA EPOP reached 77.9%, better than its pre-pandemic high of 77.4% in 2019.

Figure A displays Black, Hispanic, and white PA EPOPs between 1978 and 2023. Prime age is a key demographic to analyze because it is less influenced by the aging population or increases in college attendance (which may depress the employment rates of younger workers relative to earlier historical periods when college attendance was less common). On average, white workers have always experienced better labor market outcomes—specifically lower unemployment and higher EPOPs—than Black and Hispanic workers. Further, Black and Hispanic workers experience larger swings in labor market outcomes in business cycles, clearly shown in the larger dips in employment in and after the shaded recessions in the figure.

Due largely to the more robust policy response, it took only four years for Black and Hispanic workers to hit pre-pandemic employment peaks in this business cycle compared with the prolonged recovery from the Great Recession—when Black and Hispanic employment only hit pre-recession levels after 11 and 12 years, respectively.

Faster wage growth for Black and Hispanic workers over the last four years

Black and Hispanic workers have also experienced stronger wage growth during this recovery. Because of long-standing patterns of discrimination and occupational segregation, faster wage growth among Black and Hispanic workers is due in part to their disproportionate representation in the low-wage labor market relative to their shares within the overall workforce.

Figure B shows wage growth by race and ethnicity over the last four years compared with the prior 40 years. Because of the different periods of time, the growth rates here are annualized to better compare apples to apples. While there were short periods of decent wage growth for Black and Hispanic workers—particularly in the late 1990s and the years leading up to the pre-pandemic labor market peak in 2019—the overall impression of the 1979 to 2019 period is one of slower wage growth. In comparison, real wage growth—which accounts for high inflation—was particularly strong for these historically marginalized groups between 2019 and 2023. Black workers in particular experienced wage growth far above their historical norm: 1.4% annually over the last four years.

In our latest State of Working America Wages report, we show how the Black-white and Hispanic-white wage gaps remain much larger now than in 1979 even as the narrowing over the last four years has been significant. We also show how Black men experienced particularly fast growth relative to past performance, increasing 1.5% annualized over the last four years, compared with 0.0% on average over the prior 40 years.

While overall low unemployment and high EPOPs are certainly positive indicators of labor market strength right now, allowing the economy to recover and keep growing has translated into significant gains for historically marginalized Black and Hispanic workers. Policymakers need to keep pushing to keep the labor market pinned very tightly near full employment. The evidence is clear: If the Federal Reserve keeps interest rates higher than is needed to normalize inflation, the result may be an avoidable recession. Even a mild recession will do significant harm to Black and Hispanic workers’ opportunities for employment and wage growth.

recession unemployment pandemic federal reserve recession recovery interest rates unemploymentUncategorized

“Urban Doom Loop” Of Vacant Offices: How Far Will It Go?

"Urban Doom Loop" Of Vacant Offices: How Far Will It Go?

Via SchiffGold.com,

Even the mainstream is starting to acknowledge the massive problem…

Even the mainstream is starting to acknowledge the massive problem of vacant office buildings littering American cities, slowly turning them into post-Covid wastelands. While a few pundits are claiming (in somewhat Orwellian fashion) that the surge in empty commercial real estate is actually a chance for a utopian turnaround in the ashes of Covid weirdness, the potential for an “Urban Doop Loop” triggered by CRE is now being widely acknowledged as a possible trigger for a broader economic meltdown.

With a pre-existing problem amplified drastically by COVID-19 and then set in stone, the rising office vacancy rate has no real solution. The problem is slowly and steadily getting worse, becoming a “new normal” that simply can’t go on forever without further economic repercussions. And this time is distinct from other major downturns in that during previous shocks, like 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis, everyone more or less agreed that eventually, things would pick back up again. This time, it’s permanent.

Take just a few examples:

New York — There’s a new record for office vacancies in Manhattan, which have risen above 17%, and show no signs of slowing down. Vacancies have grown 70% in Manhattan since Covid (growing 20% nationally in the same period), with the Financial District hardest hit.

Pittsburgh — Currently sitting above 20% vacant, or 27% if you factor in subleases, it’s estimated that nearly half of the city’s commercial real estate could be empty within four years. If not reversed, a local crisis (at the very least) seems all but assured.

Portland — With the highest office vacancy rate in the nation — a mind-melting 30% or more — Portland officials are offering desperate pleas in the form of tax credits and other incentives to fill its deserted commercial buildings.

Los Angeles — Demand is so low for commercial real estate that, in one case, developers abandoned plans to build a shiny new 61-story office tower in place of an empty commercial building. Instead, they demolished it and installed a handful of EV charging stations.

There’s no great solution. Most cities are floating quixotic proposals to turn empty offices into apartments to “fix” the crisis, but this is often too expensive to be practical and requires navigating lots of bureaucratic red tape, like changes to zoning laws.

Recognizing how dependent their cities are on property taxes harvested from commercial real estate, getting municipal governments to change zoning laws actually might be the easiest part. Vacant office buildings equate to plummeting revenue, forcing cities to make up the loss by increasing taxes elsewhere or reducing spending.

For one, New York City’s commercial real estate accounts for 20% of the property tax and 10% of overall revenue, with the city comptroller projecting a $1.1 billion shortfall from vacant offices in 2024. In Boston, property taxes on office buildings comprise a staggering 22% of total revenue.

Even the most optimistic, desperately trying to see this crisis as an “opportunity” to start fresh, are being forced to acknowledge the challenges. But turning commercial spaces into residential ones and hoping for the best is one of the only few “Hail Mary” options cities have left to avoid a further implosion that bleeds into the banking sector and sets off a chain reaction.

Last year's failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, First Republic Bank, and Credit Suisse showed that more progress is required in a number of areas to ensure that banks aren't too big to fail. Read our blog for more about the lessons learned. https://t.co/PFtEp1X8Ri pic.twitter.com/HBzgWsVC2f

— IMF (@IMFNews) March 31, 2024

For the hopeful, such as Dana Lind of the Penn Institute for Urban Research, the buyer’s market in big cities provides a golden opportunity that was missed during the 2008 crisis. She hopes local buyers will use these empty buildings to invigorate cities by serving local needs, or that the empty offices will be bought by cities themselves and turned into vibrant community centers:

“Smart investors see what is happening in American downtowns four years out from the onset of the pandemic—the business fundamentals of cities like New York, Boston, or Houston are relatively stable and could even dramatically improve. Why not buy?”

Sure, fundamentals could improve. But will they? She goes on to say:

“As commercial properties fall into foreclosure in 2024, cities could take steps to better shape the city they want in the future by actually investing in those properties themselves.”

It all sounds lovely. Unfortunately, I’m less confident the CRE crisis can be contained this way, and that it won’t contribute to a broader meltdown.

Empty offices mean fewer people visiting the surrounding stores and restaurants. As the economic damage begins to snowball, the domino effect eventually reaches the banking sector, especially smaller and mid-size banks — and thus, the “Doom Loop” takes form. If we are to take the recent failure of regional firms like New York Community Bancorp as evidence, this vicious spiral may already be beginning.

CBS reported in January that office loan delinquencies were up a shocking four times compared to the previous year. In under two years, commercial real estate loans totaling $1.5 trillion are due to expire, portending disaster for the economy when the bill comes due and office owners can’t pay it. According to data from the St. Louis Fed, delinquency rates on commercial real estate loans have already ticked above their Covid peak:

Occupancy Rate on CRE Loans (Excluding Farmland), Booked in Domestic Offices, Q3 2019 to Q3 2023

In an industry that lives and dies by interest rates, the problem provides another powerful source of pressure on the Fed to cut rates this year, boosting the bottom line for commercial landlords and developers who are being squeezed by a high cost of borrowing and already scrambling to change the terms of their debt.

A recent Moody’s podcast offers a glimmer of hope that there are enough factors to offset the challenges of CRE delinquencies. But with the rate cuts that the market hoped for last year now expected to be much less significant, will put further stress on a CRE market that’s addicted to rock-bottom borrowing costs. If the Fed cuts rates too low, inflation will spiral out of control, but keep them too high, and other things (like CRE) will continue to bend and break.

Uncategorized

Bond Market’s Eerie Calm Belies Bigger Move On Way

Bond Market’s Eerie Calm Belies Bigger Move On Way

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

Volatility in US interest rate and…

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

Volatility in US interest rate and bond markets is poised to move much higher as it re-attaches to underlying fundamentals. That means higher rates and greater stock volatility, leaving especially high-duration sectors such as tech exposed to underperformance and potential downside.

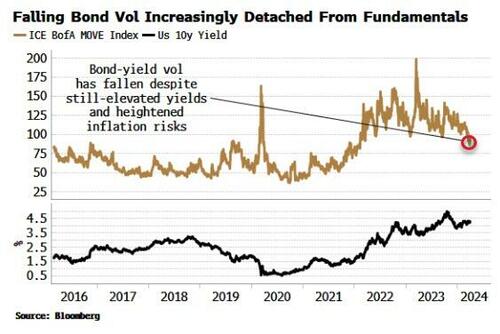

There is something of a preternatural calm to bond markets at the moment. Despite upside growth and inflation risks bubbling up, bond volatility has been in a downward trend for the past six months. It remains much lower than the highs it reached in 2022, and the spasm that was the SVB crisis in 2023.

But there are mounting signs that this won’t last, and we should soon see larger moves in yields again with an upward bias. That also means the currently-depressed VIX is poised to move higher. After a recess, volatility is coming back.

Low or falling volatility often precedes big moves. If you need an example, consider gold and silver. Their volatility fell to multi-year lows in February, ahead of both metals surging higher in recent days.

The MOVE index is the bond equivalent of the VIX. It uses a range of options on interest-rate swaps of different maturities to gauge the average level of rate volatility. As with the VIX, it was very low in the early years of the pandemic as the Federal Reserve pulled out all the stops to avert an economic calamity.

But unlike the VIX, the MOVE rose sharply as the Fed began to raise rates at a faster clip than it had done for decades, before cresting amid the turbulence of SVB’s collapse. Since then it has steadily fallen - yet this is increasingly at odds with the underlying risks.

Most focus has been on slowing inflation, but inflation volatility is telling a different story. It’s the variability in inflation as much as its level that’s a problem for bond volatility. Inflation’s volatility, after dipping, is rising strongly again. The MOVE is soon likely to correct higher to reflect rising inflation uncertainty.

The disconnect is not confined to inflation volatility. The real yield curve, which typically flattens as inflation falls, has stopped flattening, and signally failed to invert as it did in the early 1980s when Volcker unambiguously snuffed out inflation by jacking real rates considerably higher.

Yet despite today’s latent inflation risks, implied short-term rate volatility has declined rapidly back to its long-term average. The fourth generic SOFR contract (currently December 2024 expiry) is implying a daily move of only 5-6 bps in short-term rates, from more than 12 bps just last year.

That’s still much higher than the post-GFC QE era, but a more fitting comparison is the 1990s and 2000s when five bps a day was the normal daily move. Even so, with higher upside inflation risks today than back then, a five-bps implied move in short-term rates is a floor not a ceiling.

Bonds face inflation as well as upside growth risks, but markets appear to be more worried about the second than the first. Implied bond volatility might be falling, but realized volatility in nominal 10-year yields has been rising. Until early last year, volatility in real yields was also rising, but since then it has been falling.

This suggests a market expectant of upside growth risks (as leading data has been projecting, and the recent better-than-expected manufacturing ISM was a timely reminder of), but exceedingly relaxed about risks from inflation.

Yet with inflation risks rising, not falling, real-yield vol will soon rise, reinforcing nominal-yield volatility (indeed TIPS volatility and skew may be early indicators of impending stress).

That won’t be the end of it though. While the MOVE has fallen, the VIX is considerably lower on a relative basis. Going back over the last 35 years, the VIX versus MOVE ratio has only been lower 15% of the time. That will change when bond vol rises.

But what is the actual mechanism by which higher rate volatility - not necessarily higher rates - boosts stock-market volatility? In this cycle, certainly, that role is likely to be filled by equity-index correlation.

Index correlation has been driven lower by index concentration (the Magnificent Seven effect) and by falling volatility in rates markets. But correlation is now so low it can only really go in one direction, and do so abruptly. It’s the muted correlation between stocks that’s been keeping the VIX low despite the volatility of many single stocks being quite elevated.

Stock-market correlation and bond volatility typically move together, as stocks’ valuations change more as the variance in rates rises. As the chart below shows, the central trends of the MOVE index and index correlation are closely aligned, ex the monthly up-and-down noise in the latter.

Thus a rise in bond volatility would lead to a rising index correlation, which would very quickly translate into a higher VIX.

Higher equity vol would be destabilizing for the stock market. While it may not lead immediately to a broad selloff, in an environment of rising inflation risks high-duration sectors such as tech are prone to underperformance.

Fortunately, though, stock hedges are still cheap. For example, a 25 delta (~4% out-of-the-money) put option on the XLK tech sector ETF with a one-month expiry costs about 3.2% on an annualized basis. That’s about as cheap as it gets.

“Let no man claim he has got through the perils of winter till at least the 7th of May”, counseled the writer Anthony Trollope. It may be April, but the perils are not over for the bond - or equity - markets, and may in fact just be getting started.

Uncategorized

What is metabolism? A biochemist explains how different people convert energy differently − and why that matters for your health

An elite athlete’s metabolism mostly looks different from a patient with COVID-19 − but their occasional similarities can reveal important insights…

If you’ve spent any time scrolling through the health and wellness corners of social media, you’ve likely come across many products claiming to improve your metabolism. But what exactly is your metabolism?

Everything you expose your body to – from lifestyle to an airborne virus – influences your physical characteristics, such as your blood pressure and energy levels. Together, these biological characteristics are referred to as your phenotype. And the biological system that most directly influences your phenotype is your metabolism.

So if you are eating something, take medications, smoke or exercise, your metabolism is responsible for transferring that biological information throughout your body for it to adapt.

Metabolism is energy conversion

Your metabolism consists of a network of tens of thousands of molecules and proteins that convert the food you eat into the energy and building blocks your body uses to move, grow and repair itself. At the chemical level, energy metabolism begins when the three macronutrients – carbohydrates, fats and protein – are broken down atom by atom to release electrons from chemical bonds. These electrons charge components in cells called mitochondria.

Akin to how batteries work, mitochondria harness this electrical potential to create a different form of chemical energy that the rest of the cell can use.

Simply put, a primary role of metabolism is to convert chemical energy into electrical energy and back into chemical energy. How this energy is transferred throughout the body might play a central role in determining whether you’re sick or healthy.

I am a biochemist who studies the various networks of metabolism that are used as your body changes. My team and I have been able to define specific traits of metabolism, such as the presence and amount of certain metabolites – products made from breaking down macronutrients – across a wide range of conditions.

These conditions include diseases such as COVID-19, diabetes, multiple sclerosis and sickle cell anemia, to experiencing unique environments such as radiation exposure, high altitude, aging and sports performance. Each of these settings influences which parts of your metabolic network are used and how they communicate with one another.

Elite athletes define the upper limits

Given the alarming rise in obesity and its associated metabolic syndrome – about 1 in 8 people across the globe were living with obesity in 2022 – defining a healthy or impaired metabolism can help identify what’s gone wrong and how to address it.

Elite athletes offer a prime population to study metabolic function at its best, since their network of molecular and chemical reactions must be finely tuned to compete on the world stage.

Traditionally, lactate threshold has been a critical measure of athletic performance by pinpointing exercise intensity when lactate starts to rise in muscles and blood.

Contrary to common belief, lactate is not merely a waste product but an energy source as well, and it accumulates when it’s produced faster than mitochondria can use it. While a moderately active person might reach their threshold at an exercise intensity of around 2 watts per kilogram, elite cyclists can sustain an intensity up to nearly two to three times higher.

When comparing the lactate thresholds of a group of elite cyclists, we found that the cyclists with higher thresholds had markers of better mitochondrial function. One of these markers was higher production of coenzyme A, a molecule that shuttles carbon around cells and is important for breaking down carbs, amino acids and fat into chemical energy.

Higher-performing cyclists also appeared to burn more fat and burn fat longer during a multistage world tour compared with lower-performing cyclists.

Dysfunctional metabolism in diseases like COVID-19

Your metabolism also changes if you get an acute illness such as COVID-19.

In contrast to elite cyclists, COVID-19 patients have an impaired ability to burn fat that appears to persist with long COVID. The blood of these patients at rest is similar to that of an elite cyclist’s at exhaustion. Considering that exercise intolerance frequently occurs with long COVID, this suggests mitochondrial dysfunction may play a role in COVID-related fatigue.

Burning fat uses a lot of oxygen. COVID-19 damages the red blood cells that deliver oxygen to organs. Because red blood cells have a limited ability to repair themselves, they might not function as well during the remainder of their roughly 120-day life span. This may partially explain why COVID symptoms last as long as they do in some people.

Blood donors define the middle

Blood transfusions are one of the most common clinical procedures. Over 118 million pints of blood are donated by millions of people worldwide every year. Because blood donors undergo screening to ensure they are healthy enough to donate, they are typically moderately healthy, somewhere between acute illness and elite athletic performance. Blood donors, coming from every walk of life, also have a diverse range of biological traits as a study population.

My team and I looked at blood from over 13,000 blood donors to shed light on their metabolic diversity. We found specific traits that could predict how well a donor’s blood would work in patients, which also has implications for how well that blood works in the donors themselves.

We found that one of these traits is a metabolite called kynurenine, which is produced from the breakdown of the amino acid tryptophan. We found that blood from donors with higher levels of kynurenine was less likely to restore hemoglobin levels in transfusion recipients compared with donors with lower kynurenine levels.

Kynurenine levels are higher in older donors and donors with a higher BMI, and may potentially be tied to higher levels of inflammation. In support, our group also found that kynurenine increases dramatically in runners participating in the 171-kilometer (106 miles) Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. In addition, we also identified that kynurenine is a strong marker of COVID-19 severity.

The relationship between metabolites and health outcomes reinforces the important role metabolism plays in the body. Getting a better understanding of what healthy metabolism looks like can offer unique insights into how it deviates when someone gets sick and may offer new approaches to medical treatments.

In addition to his appointment at the University of Colorado, Travis Nemkov is an Affiliate Investigator of Vitalant Research Institute and a co-founder of Omix Technologies.

bonds covid-19-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoParexel CEO to retire; CAR-T maker AffyImmune promotes business leader to chief executive

-

Spread & Containment3 weeks ago

Spread & Containment3 weeks agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

International4 weeks ago

International4 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International4 weeks ago

International4 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized2 days ago

Uncategorized2 days agoVaccinated People Show Long COVID-Like Symptoms With Detectable Spike Proteins: Preprint Study

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoEvidence And Insights About Gold’s Long-Term Uptrend

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoA Global, Digital Coup d’État

-

Spread & Containment19 hours ago

Spread & Containment19 hours agoOura Ring launches genius new feature to take on Apple Watch