Uncategorized

A memorial in Yiddish, Italian and English tells the stories of Triangle Shirtwaist fire victims − testament not only to tragedy but to immigrant women’s fight to remake labor laws

On Oct. 11, 2023, a new memorial was unveiled at the site of the 1911 fire. A cadre of young Jewish women helped push for change in the wake of the tr…

The 10-story Brown Building, site of one of the deadliest workplace disasters in United States history, stands one block east of Washington Square Park in New York City. Despite three bronze plaques noting its significance, it has long been easy to pass by without further thought.

On March 25, 1911, however, thousands of New Yorkers gathered outside what was then known as the Asch Building, home of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Drawn by a brief but raging inferno, they bore horrified witness to dozens of factory workers with no way to escape gathering on the ninth-floor window sills, desperately jumping, and smashing onto the sidewalks far below.

Horse-drawn fire crews responded within minutes to reports of the fire, which broke out on a Saturday afternoon at closing time, and it took only a half-hour to douse the flames. But the fire had had its way.

One hundred and forty-six people lost their lives. Most of those who died worked on the ninth floor, where safety measures consisted of little more than pails of water, despite the potential fire bomb around them: overflowing bins of discarded cloth and lint, combined with tissue-paper patterns hung across the ceiling. Locked doors, an inadequate fire escape and other fire code violations meant many workers could find no way out except the windows.

Firemen were left to stack the lifeless bodies on the sidewalk. The vast majority were girls or young women: meagerly paid laborers, and most of them Jewish or Italian immigrants.

On Oct. 11, 2023, the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition dedicated a striking memorial at the site of this tragedy. The initial installation features a stainless steel ribbon extending in two parallel strands along the ground floor, displaying victims’ names and survivors’ testimony, written in their native languages: English, Yiddish and Italian. Over the next few months, another gently twisting ribbon traveling from the window sill of the ninth floor to the ground level and back up again will be added.

The memorial offers a bold and graceful reminder not only of the fire but of its imprint on the world we inhabit today.

When I asked the students in my history class at the University of Michigan if they had heard of the Triangle fire, I was shocked to see almost all raise their hands. Many were familiar with how the disaster inspired the growth of labor activism and worker protections. Few of them, however, had thought about the central role of American Jewish women, the focus of my research.

Tense 2 years

Only two years before the fire, a walkout over working conditions at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory had sparked a series of labor actions that culminated in the Uprising of the 20,000, the largest American women’s strike ever.

That disciplined activism was led by a small cadre of young Jewish immigrant working-class women. Years earlier, they had essentially created a branch of their own – Local 25 – within the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Their example led to a surge of strikes nationwide and forced the labor movement to finally take the needs of unskilled workers and women workers seriously.

The Triangle bosses and other owners hired thugs to assault strike leaders and picketers. The police likewise felt free to beat the picketers, which only abated when upper-class partners in the Women’s Trade Union League joined the picket lines – raising fear among the police that they might be striking society matrons.

The Triangle Factory was among the 339 shops that “settled” with the union in February 1910, with concessions that included higher wages, a 52-hour week, four paid holidays per year and a promise to no longer discriminate against union members.

The strikers’ call for better safety standards, however, had been ignored by the male union representatives and owners who had worked out the settlement.

Moral force

Local 25 grew from a few hundred to 10,000 members over the course of the 1909-10 strike. That organizing prowess would be seen again in the wave of protest and indignation that followed the 1911 fire.

The unions’ strength could be seen in the funeral march that accompanied the fire’s seven unidentified victims to a municipal burying ground, as a crowd of 400,000 assembled to march or watch the procession.

The power of the activists’ moral indignation emerged in full force at a memorial meeting held a few days later. Workers grew restive as wealthy philanthropists, city officials and liberal reformers promised investigatory commissions – which they feared would mean little real change.

Rose Schneiderman, one of the working-class immigrant labor activists who had helped organize the 1909 strike, was also on the platform. Reformer Frances Perkins, who would soon become a close ally, noted Schneiderman trembling over the loss of comrades, friends and co-workers.

Schneiderman took the podium, excoriating the industry’s brutality and focusing on the unrealized power of the workers themselves. “I would be a traitor to those poor burned bodies,” she declared, “if I were to come here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public – and we have found you wanting.”

“I know from experience it is up to the working class to save themselves,” Schneiderman told the audience.

Birth of the New Deal

Yet the working class ended up needing allies like Perkins, who was instrumental in establishing a citizens’ Committee on Safety, and then a legislative Factory Investigating Commission as well.

On the day of the fire, Perkins had been enjoying tea at a friend’s house on Washington Square and rushed toward the commotion across the park, arriving on the scene to see bodies falling from the sky. That scene and Schneiderman’s speech left an indelible impression on her – as they did on many New Yorkers.

For several reasons, including public outcry about the fire, this was the moment when New York City’s political machine began to shift its focus and address workers’ needs. Schneiderman and other activists worked with Perkins on investigations that led to the overhaul of New York’s safety and labor laws, such as a 54-hour maximum work week.

The young women whose pain had galvanized public response continued their union work, traveling around the country to help organize many of the strikes their activism inspired. Some also made an impact at the governmental level. Schneiderman became a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and influenced her views on workers’ needs, as well as those of her husband, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Perkins became President Roosevelt’s secretary of labor in 1933 and was the first woman to serve in a U.S. cabinet position. She brought the New York reforms born in the wake of the fire into the New Deal, the slew of social programs the Roosevelt administration introduced to help Americans struggling through the Great Depression.

Schneiderman, too, had a role: the only woman to serve on the New Deal’s Labor Advisory Board. As Perkins later recalled, the day of the Triangle fire was “the day the New Deal was born.”

For 112 years, the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory have called out silently from the sidewalks and window frames of the Brown Building, which is now part of New York University’s campus. The new memorial calls on the passersby to stop, note and honor that one horrific half-hour, etched indelibly into the story of the city and the nation.

Karla Goldman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

depressionUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

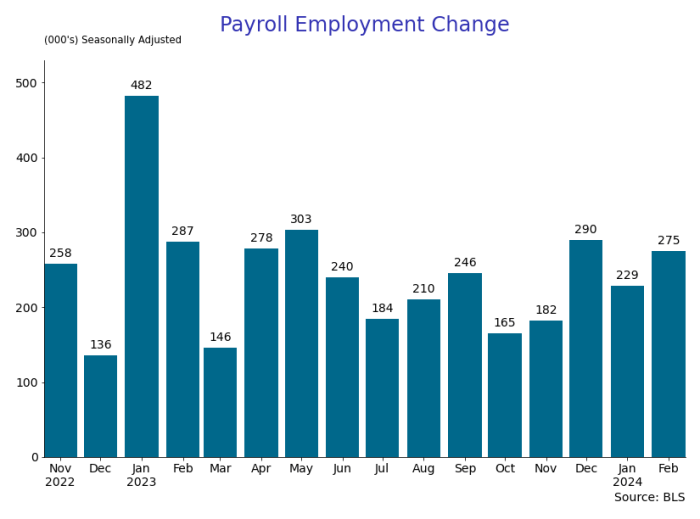

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

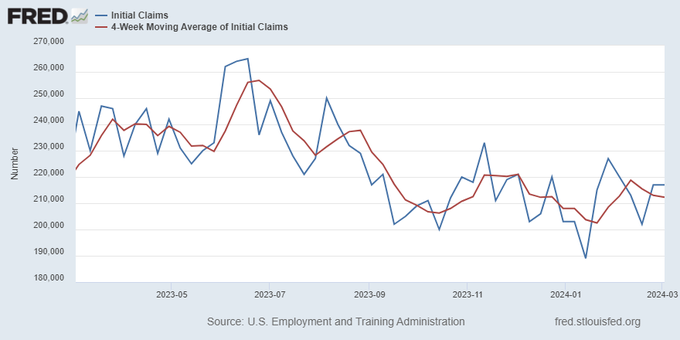

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

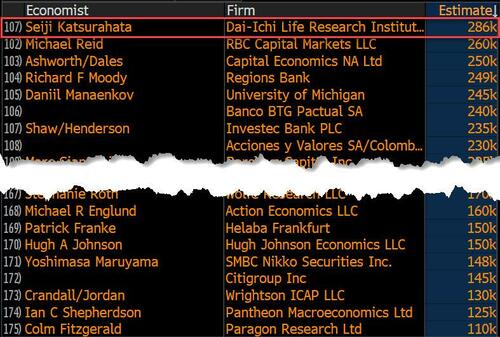

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges