TikTok and Instagram are full of misleading information about birth control — and wellness influencers are helping drive these narratives

Social media has transformed how we connect and communicate online — affecting even how we get health information.

There’s been an increase in content posted on TikTok and Instagram recently discussing the alleged dangers of birth control. Content creators have shared concerns about the pill’s side-effects ranging from weight gain to low libido and fluctuating moods. Other claims are misleading because they exaggerate the risks associated with contraception, cancer and infertility.

Many of these posts and videos are created by wellness influencers who foster the impression of authenticity by sharing their personal lives with their followers. This presents them as trustworthy, despite lacking medical qualifications, making it difficult for people to discern what to believe and who to trust.

The wellness movement first emerged in the US in the 1970s as an alternative to the standard medical treatment model. Rather than framing health as the absence of disease, pioneers of the wellness movement conceived of wellness as a lifestyle driven towards the pursuit of optimal health and vitality.

The movement was inspired by High Level Wellness, a book published in 1961 by statistician and medical doctor Halbert L. Dunn. Dunn believed wellness involved a holistic approach to health, encompassing the mind, body and spirit to maximise a person’s potential.

The ethos and alternative lifestyle practices associated with the wellness movement resonated with the hippy movement. It also coalesced with other countercultural movements – such as the civil rights movement and the women’s movement.

The women’s movement championed a woman’s right to bodily autonomy, critiquing what they perceived to be a patriarchal medical system in post-war America. Activists fought for a woman’s right to be involved in decisions about her health and the treatments she received.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our 20s and 30s. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

If you get your financial advice on social media, watch out for misinformation

Is it ethical to watch AI pornography?

Women’s rights activists also fought for reproductive rights, including the right of unmarried women to legally be prescribed contraceptives.

But today’s online backlash to birth control occurs in a context where women’s reproductive rights have been curtailed. If natural contraceptive methods result in an unwanted pregnancy, some women no longer have the right to choose. This raises questions about how the pill has been re-framed from a source of liberation to harmful by some female wellness influencers.

The role of social media

Social media has changed how we connect and communicate online. It’s also lowered the barrier to achieving fame, enabling content creators to establish personal brands and large followings by sharing their experiences and lifestyle advice.

Unlike the doctor-patient relationship, which is characterised by professional distance, influencers establish trust and intimacy by fostering the impression of accessibility with their followers. This typically involves providing backstage access to their personal lives and being vulnerable with their audience by sharing personal failures and triumphs.

There’s a tendency to trust those we perceive to be like us. This is why many women may consult friends and relatives for health information. People trust influencers because they appear accessible, authentic and autonomous – independent from the media and the political and commercial interests associated with traditional experts and authority figures.

The inclination to look beyond institutional expertise for health information is not new. Scientific knowledge has always been constructed through a combination of expert and non-expert voices. What has changed is that science communication is happening online, with social media enabling people to create and broadcast content publicly on these sites – regardless of whether they’re an expert or not. In some cases, disinformation is being collectively created and shared online.

Where the wellness movement was once primarily associated with liberal ideologies, many journalists and researchers have recently observed an intersection between wellness discussions and far-right politics. This shift was accentuated by the pandemic, when wellness became a gateway to misinformation and conspiracy theories.

Despite this convergence, the backlash against contraception cannot be reduced solely to politics. While some conservative influencers encourage natural contraceptive methods (such as timing sex to menstrual cycles) instead of synthetic hormonal contraception, many influencers have more generic concerns about the financial and political incentives of corporations and pharmaceuticals companies that have persisted for decades.

These concerns often manifest in critiques of experts and elites, who they see as compromised by money and power.

Instead, wellness influencers commonly prioritise what my colleague and I previously termed “native expertise” – knowledge derived from intuition and experience rather than professionals. This often manifests in the promotion of lifestyles depicted as natural, ancestral or primal. The experts and doctors these influencers trust tend to be those rejected by the establishment.

Many wellness influencers today share similar concerns as the women’s movement in the 1970s about male doctors telling women what to do with their bodies. They want to be heard, believed and gain control over their body. But one of the striking differences between the women’s movement and the female entrepreneurs championing women’s health online, is that the advice influencers share is often monetised. Most influencers appear to be less interested in political change and more interested in promoting a specific lifestyle, product or service.

Why this matters

In the late 20th century, the wellness movement gave way to the wellness industry. Wellness became a commodity.

Social media has further commodified wellness, with influencers using wellness to create lucrative personal brands. The financial gains that can be made from sowing distrust and establishing oneself as a credible alternative make women’s wellness a confusing space for consumers to navigate.

Influencers typically share opinions rather than facts, making their content difficult to regulate as they often user disclaimers to legally protect themselves. Rather than diminish their authority, these anecdotes are central to it – with influencers trading on their apparent ordinariness.

Read more: The online wellness industry: why it's so difficult to regulate

Those critical of contraception could be motivated by a variety of different factors and experiences and it would be a mistake to reduce all criticisms to misinformation. But who we trust influences what we believe. If the backlash to contraception highlights anything, it’s that misinformation is more about trust, identity and relationships than information.

Stephanie Alice Baker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

treatment pandemic

International

World’s Biggest M&A Deal Is Terrible For Bonds

World’s Biggest M&A Deal Is Terrible For Bonds

Four years ago, we wrote an article, mocking the unspeakable reality that it appeared "The…

Four years ago, we wrote an article, mocking the unspeakable reality that it appeared "The Fed and The Treasury had now merged"...

Last week, that reality dawned on one of Wall Street's best and brightest as BofA Chief Investment Strategist Michael Hartnett headlined his latest note with a 'zeitgeist' quote that sounded awfully familiar:

"Biggest piece of M&A in past 12 months was the merger of Treasury & Fed.”

And this morning, Bloomberg macro strategist Simon White takes up the story below, noting that monetary and fiscal policy in the US is becoming more intertwined as the Federal Reserve and the Treasury - implicitly or otherwise - increasingly coordinate their actions.

That’s a structural negative for US Treasuries, and signals an end to the long underperformance of commodities and other real assets.

Reflecting on the quote above Michael Hartnett of BofA - describing the greater coordination of fiscal and monetary policy in the US and the winnowing away of the Fed’s independence from the Treasury - White agrees that, viewed as an M&A deal, it’s certainly massive, given the Fed’s $7 trillion balance sheet and the government’s $34 trillion of debt.

More importantly, it’s hazardous for Treasuries as it tilts the risks for persistently higher inflation firmly to the upside, even though the market continues to be under-appreciative of the ever-more malign landscape. Positioning in USTs has fallen this year, but it is still likely to be net long, while outright shorts remain near survey lows, corroborated by the muted short interest in Treasury ETFs such as the TLT.

At the same time as entrenched inflation is bad for fixed income, it’s also very positive for real assets such as commodities. They have relentlessly underperformed financial assets - stocks and bonds - over the last four decades.

Governments are inherently inflationary. Wealth is very unevenly distributed, with many dollars held in only a few hands. But every person has exactly one vote. Thus there is an incentive for governments to take wealth from the rich — where it is mainly saved — and redistribute it to the less well-off, where it is more likely to be spent.

The sort of spending governments engage in in the run-up to elections is likely to be discretionary and debt-funded — which government wants to raise taxes ahead of a vote? Mandatory spending, such as entitlement programs and defense, is likely to see its biggest boost when the economy is in a slump. Increases in discretionary spending, on the other hand, more often than not happen when the economy is growing, and therefore are more likely to fan inflation.

Discretionary spending in the US had already started to grow before the pandemic, and its five-year growth rate has leveled off at an elevated level and not yet fallen. As the chart below shows, longer-term rises in discretionary spending precede structural rises in inflation. Today’s spending is the largest ever seen in the US outside of war or recession.

How is government spending stoking inflation in this cycle? Mainly through supporting corporate profits. Deeper fiscal deficits lead to higher profits and profit margins (see chart below), as net spending in one sector must lead to net saving in the others, with the corporate sector the main beneficiary as government deficits support spending in the household sector.

This is a marked change from the 1970s when wages directly drove prices higher. With much less trade-union membership and weakened union power, that’s less of a risk today.

But profits are lining up to be the main vector of persistent and elevated inflation in this cycle. The unique conditions of the pandemic allowed firms to raise profit margins almost as fast as they ever have done. A profit-price-wage spiral is a greater likelihood, and could already be underway.

The risk is that an increase in margins leads to higher prices and then to higher wages. Margins are increased again, but to a greater level than before, to maintain profits in real terms as prices have risen since the last increase.

Economy-wide margins are off their recent highs, but are still significantly elevated compared to their pre-pandemic levels. Labor costs in the decades running up until 2020 made up the bulk of corporate prices, accounting for over half of them on average. But that relationship has inverted since the pandemic, with profits now making up 45% of selling prices, versus under 30% for the cost of labor. Profits now drive prices.

Elevated government deficits can keep the carousel going by supporting spending. The CBO projects discretionary outlay’s five-year growth rate should fall back toward 10% in the next few years from over 35% now. But that’s smoking hopium. The expectations electorates have from their governments markedly rose in the pandemic, with the sovereign expected to underwrite an ever widening basket of risks. The “fiscal put” is becoming embedded and the longer spending keeps rising to pay for it, the harder it will be to reverse.

Government borrowing to fund discretionary spending is a highly inflationary mix on its own, but the addition of a compliant central bank fans the flames further. Notionally the Fed is still independent, but in actuality its maneuverability is increasingly circumscribed for three reasons:

-

the large amount of Treasuries outstanding and the rising interest payable on them;

-

the ungainly size of the Treasury’s account at the Fed;

-

and the increasing proportion of short-term bills, i.e. short-term liabilities that are very money-like.

History is replete with examples of large government deficits monetized by central banks preceding high or hyper-inflation, from China in the late 1940s, to Greece in the early 40s and to Zimbabwe early in this century. That’s not to say we should expect the US to see price growth hit such stupefying levels, but to underscore that spendthrift governments and subservient central banks is a terrible combination for price stability.

Treasuries are unlikely to thrive in this environment.

Nothing moves in a straight line, but the net path for yields is likely to be higher in the coming months and years. Embedded inflation is also likely to drive increasing demand for real assets such as property and commodities, ending their decades of underperformance.

Inflation is one of the most regressive of taxes, as well as being one of the hardest to lower. Almost everyone loses when it is elevated. Even though M&A deals are meant to be value creating, this one is likely to be precisely the opposite.

Spread & Containment

US PMIs Scream Stagflation As Manufacturing ‘Contracts’, Prices Rise, Heaviest Job Cuts Since GFC

US PMIs Scream Stagflation As Manufacturing ‘Contracts’, Prices Rise, Heaviest Job Cuts Since GFC

After a mixed bag from preliminary April…

After a mixed bag from preliminary April European PMIs (Services strong-er, Manufacturing weaker-er, surging prices)...

“Accelerated increases in input costs, likely driven not only by higher oil prices but also, more concerningly, by higher wages, are a cause for scrutiny Concurrently service-sector companies have raised their prices at a faster rate than in March, fueling expectations that services inflation will persist. ”

and after March US PMIs exposed the end of the disinflation narrative...

"Most notable was an especially steep rise in prices charged for consumer goods, which rose at a pace not seen for 16 months, underscoring the likely bumpy path in bringing inflation down to the Fed's 2% target. ”

...S&P Global's preliminary US f°r April just dropped and they were ugly with both Manufacturing and Services disappointingly dropping further as the former dropped back into contraction:

-

• Flash US Services Business Activity Index at 50.9 (Exp: 52.0; March: 51.7) - 5-month low.

-

• Flash US Manufacturing PMI at 49.9 (Exp 52.0; March: 51.9) - 4-month low.

Source: Bloomberg

Commenting on the data, Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence said:

“The US economic upturn lost momentum at the start of the second quarter, with the flash PMI survey respondents reporting below-trend business activity growth in April. Further pace may be lost in the coming months, as April saw inflows of new business fall for the first time in six months and firms’ future output expectations slipped to a five-month low amid heightened concern about the outlook.

“The more challenging business environment prompted companies to cut payroll numbers at a rate not seen since the global financial crisis if the early pandemic lockdown months are excluded.

After March showed accelerating prices, flash April data confirmed the trend

“Notably, the drivers of inflation have changed.

"Manufacturing has now registered the steeper rate of price increases in three of the past four months, with factory cost pressures intensifying in April amid higher raw material and fuel prices, contrasting with the wagerelated services-led price pressures seen throughout much of 2023.”

So slower growth and much faster inflation - that does not sound like a recipe for rate-cuts... in fact quite the opposite.

Uncategorized

New Home Sales Increase to 693,000 Annual Rate in March

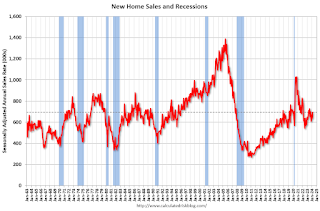

The Census Bureau reports New Home Sales in March were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 693 thousand.

The previous three months were revised down combined.

Sales of new single‐family houses in March 2024 were at a seasonally adjusted an…

The previous three months were revised down combined.

Sales of new single‐family houses in March 2024 were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 693,000, according to estimates released jointly today by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is 8.8 percent above the revised February rate of 637,000 and is 8.3 percent above the March 2023 estimate of 640,000.Click on graph for larger image.

emphasis added

The first graph shows New Home Sales vs. recessions since 1963. The dashed line is the current sales rate.

New home sales were close to pre-pandemic levels.

The second graph shows New Home Months of Supply.

The months of supply decreased in March to 8.3 months from 8.8 months in February.

The months of supply decreased in March to 8.3 months from 8.8 months in February. The all-time record high was 12.2 months of supply in January 2009. The all-time record low was 3.3 months in August 2020.

This is well above the top of the normal range (about 4 to 6 months of supply is normal).

"The seasonally‐adjusted estimate of new houses for sale at the end of March was 477,000. This represents a supply of 8.3 months at the current sales rate."Sales were above expectations of 670 thousand SAAR, however, sales for the three previous months were revised down, combined. I'll have more later today. home sales pandemic

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoParexel CEO to retire; CAR-T maker AffyImmune promotes business leader to chief executive

-

Spread & Containment2 weeks ago

Spread & Containment2 weeks agoClimate-Con & The Media-Censorship Complex – Part 1

-

International1 week ago

International1 week agoWHO Official Admits Vaccine Passports May Have Been A Scam

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoJ&J’s AI head jumps to Recursion; Doug Williams resigns as Sana’s R&D chief

-

Spread & Containment2 weeks ago

Spread & Containment2 weeks agoFDA Finally Takes Down Ivermectin Posts After Settlement

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoVaccinated People Show Long COVID-Like Symptoms With Detectable Spike Proteins: Preprint Study

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCan language models read the genome? This one decoded mRNA to make better vaccines.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoWhat’s So Great About The Great Reset, Great Taking, Great Replacement, Great Deflation, & Next Great Depression?