International

The Fed’s interest rate hikes 2022–2023: Timeline & discussion

Through its rate hikes in 2022 & 2023, the Fed aimed to contain inflationary forces and maintain “maximum” levels of employment — all while steering…

Kevin LeVick/TheStreet

The Covid-19 pandemic changed the world as we know it — more than 9.6 million people died, and countless more became ill: according to the CDC, 77% of Americans have been infected at least once.

At the outset of the pandemic, people were stuck under stay-at-home restrictions, which caused businesses to shutter and snarled supply chains. GDP plummeted, the stock market crashed, and millions of people lost their jobs.

Through legislation like the CARES Act, the U.S. government granted forgivable loans to small businesses and sent stimulus checks to individuals and families struggling to make ends meet. In such a difficult time, the last thing the U.S. Federal Reserve wanted to do was make it harder for Americans to find work. That’s why the Fed waited so long to start hiking interest rates.

What are Fed rate hikes?

It’s important to note that the Fed does much more for the economy than simply adjust the dial on interest rates. It regulates the country’s banks, ensures the stability of its financial markets, and sets policies that maintain its dual mandate of promoting stable prices and maximum employment for the American people.

Unemployment levels skyrocketed during the Covid-19 pandemic, peaking at 14.7% in April 2020, and they wouldn’t return to pre-pandemic levels until March 2022. Therefore, the Fed’s first goal was to foster a favorable environment for job creation. It actually cut interest rates to zero in March 2020 and held them steady for two years.

Low interest rates make it easier for businesses to expand, homebuyers to obtain mortgages, and banks to lend to each other, all of which spur economic growth — and thus create more jobs.

For example, after the Financial Crisis of 2007–2008 and the subsequent Great Recession, the longest economic downturn since the Great Depression, the Federal Reserve, led by then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, slashed interest rates to nearly 0% for 6 years. Because businesses could access more credit, many hired more workers. As a result, the job market strengthened, ushering in one of the longest bull markets the United States has ever known.

Related: Looking back at the banking crisis of 2023

According to the Fed, the economy reaches “maximum” employment levels when everyone who wants a job has one — without generating inflationary pressures. But when inflation starts to creep in, the Fed must take the appropriate steps to tame these pressures, and one of the first ways it does so is by hiking interest rates.

How does the Fed decide when and how much to increase interest rates?

When the Fed meets every six weeks at its Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings, it looks at a wide range of economic indicators to determine whether to maintain, raise, or lower interest the Fed Funds rate, which is the interest rate range at which banks lend to one another and the prevailing interest rate that informs all others.

One of the reports it watches closely is the Employment Situation Report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This contains a survey of 60,000 U.S. households conducted by the U.S. Census that determines the country’s unemployment rate. The Fed also keeps an eye on the percentage of the population actively looking for work (the Labor Force Participation Rate), the number of people who have left their jobs (Labor Turnover Survey), and the number of job openings (JOLTS), to name a few.

But during the Covid-19 pandemic, in August 2020, Fed Chair Jerome Powell made an important change to the Fed’s overall strategy, calling maximum employment “a broad-based and inclusive goal.” He went on to say:

“Our policy decision will be informed by our assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level rather than by deviations from its maximum level… This change may appear subtle, but it reflects our view that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation.”

—Fed Chair Jerome Powell

Basically, that meant that the Fed wouldn’t be hiking interest rates just because unemployment levels were falling.

The Fed waited until March 2022 to raise interest rates because it wanted workers in low- and moderate-income communities to feel the benefits of a strong job market, something that became apparent during its “Fed Listens” tour, a series of events involving a diverse group of Americans, from union members to small business owners, retirees, and more.

“One of the clear messages we heard was that the strong labor market that prevailed before the pandemic was generating employment opportunities for many Americans who in the past had not found jobs readily available. A clear takeaway from these events was the importance of achieving and sustaining a strong job market, particularly for people from low- and moderate-income communities,” the Fed stated.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) reported that Covid-19-related employment changes were “inequitably patterned by race, gender, and education,” as Black, Latinx, and non-white women without a high school degree faced the highest percentage of job losses. For example, Black, Latinx, and other non-white men without a high school degree were 90% less likely to switch to remote work than similar demographics with a high school degree, and the NIH added that none of the men it interviewed between May 2020 and May 2021 were able to make that transition.

The White House also found that Black Americans’ unemployment levels peaked at 16.8% during the Covid-19 pandemic, which was substantially higher than the national average of 14.7%. And since 2020, the report discovered that Black men and women had particularly benefited from the exceptionally tight labor market, seeing wages rise 7.8% compared with just 6.3% overall, as they transitioned into higher-paying jobs and industries.

The Fed’s goal of inclusivity wasn’t solely centered on racial demographics. Powell also noted that the Fed monitored unemployment rates and participation rates for different age groups as well as genders. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, unemployment levels for women, for instance, peaked at 15.5% in April 2020, which was 0.8% higher than the national average. In testimony to Congress in February 2021, Powell noted that many women had left the workforce to care for their families during the pandemic — and added that improved access to child care might help them return to their jobs.

How do rate hikes curb inflation?

At the Fed’s January 2022 FOMC press conference, Powell stated that the Fed believed that “maximum” employment levels had been achieved. And while the Fed kept interest rates at near-zero levels, he predicted a rate hike in the near future, eyeing “a backdrop of elevated inflation.”

Inflation, which is defined as a period of rising prices, can spell disaster for an economy because businesses raise prices and workers expect more money, but people don’t actually have more money to compensate, which results in lower demand, souring confidence, and often, recession.

By 2021, the goods and services people needed to live their everyday lives had suddenly become more expensive. Powell attributed this to the supply and demand imbalances created by the pandemic and labeled it a “transitory” phenomenon at his July 28 press conference. At the January 2022 Fed meeting, he added that the Fed expected inflation would decline over the year.

But it didn’t.

Between March 2020 and January 2022, the average annual inflation rate was 6.34% according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which resulted in an 11% increase in prices as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The CPI rose to 9.1% in June 2022 alone, and food and energy prices soared — Russia’s invasion of Ukraine only exacerbated the problem. The Fed needed to take drastic measures to get the economy back on track.

Powell took a page from the book of another Fed Chair, Paul Volcker, who back in the 1970s had defeated the inflation monster. Inflation was even worse then than it was in the post-pandemic era, hitting 11% by 1979 and accelerating by 1% each month.

Volcker combated inflation by raising interest rates to staggering levels.

In just 2 years, Volcker hiked interest rates from 11.2% to an astounding 20%, effectively putting a temporary stranglehold on the economy. (That’s because when interest rates are high, banks are less willing to lend, businesses may cut their workforce, and the economy contracts.)

But in the end, Volcker’s tough-love tactics proved successful. By December 1982, the CPI was flat, and by 1986, it would hit the Fed’s 2% target.

How many times did the Fed increase rates? When is the next Fed rate hike?

The Fed hiked interest rates a total of 11 times between March 2022 and January 2024. This made the cost of borrowing more expensive, and the housing market slowed. The stock market also clocked in a lousy 2022, with the S&P 500 losing 19.4%.

But in 2023, the results the Fed was hoping for finally came to light as headline inflation fell by 3.1%. GDP continued to grow — by 3.3% in the fourth quarter alone, which was well above the 1.5% consensus estimates. And despite higher rates, consumer spending remained strong. Many believe the Fed achieved its hoped-for “soft landing,” which happens when it tightens interest rates but avoids a recession.

The Fed’s last rate hike, a 25-basis point increase, was on July 27, 2023.

As of January 2024, the Fed funds rate stands at 5.4%, its highest level since 2002.

Analysts predict the Fed will hold interest rates steady through its next few meetings and could begin cutting them as early as May 2024. (Access the Fed’s meeting schedule.)

A timeline of the Fed's interest rate hikes 2022–2023

- March 3, 2020: Citing “evolving risks to economic activity” from the coronavirus outbreak, the Fed held an emergency meeting, cutting interest rates by 0.5% to 1.0–1.25%

- March 11, 2020: The World Health Organization (WHO) declares Covid-19 a global pandemic

- March 15, 2020: In another emergency meeting, the Fed slashes rates to zero (a range of 0–0.25%) and launches a $700 billion quantitative easing program

- March 16, 2020: The Dow falls 12.9%, triggering a stock market crash. It would go on to lose a total of 37% before ending the year with a 7.3% gain

- April 2020: U.S. unemployment reaches an average of 14.7%, its highest level since 1948, although job losses for women and minorities are even higher

- August 28, 2020: At an economic symposium in Jackson Hole, the Fed announces a new strategy that calls maximum employment “a broad-based and inclusive goal”

- July 28, 2021: The Fed holds rates steady at near-zero levels, labelling rising inflation a “transitory” phenomenon

- January 26, 2022: Powell states that “labor market conditions are consistent with maximum employment” and predicts future interest rate hikes

- February 24, 2022: Russia invades Ukraine

- March 16, 2022: The Fed makes its first interest rate increase since 2018, raising rates by 0.25% to a level of 0.25–0.50%

- May 5, 2022: The Fed increases interest rates 0.50% to 0.75–1.00% and states that it anticipates ongoing increases to be “appropriate”

- June 2022: Inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), peaks at 9.1%

- June 16, 2022: The Fed raises rates 0.75% to 1.50–1.75%

- July 28, 2022: The Fed hikes rates another 0.75% to 2.25–2.50%

- September 22, 2022: The Fed delivers another 0.75% rate increase, bringing rates to 3.00–3.25%

- November 3, 2022: It increases rates by 0.75% to 3.75–4.00%, adding that it is “prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge”

- December 15, 2022: This time, the Fed raises rates by 0.5% to 4.25–4.50%

- February 2, 2023: It adds another 0.25% increase to 4.50–4.75%

- March 23, 2023: The Fed increases interest rates by an additional 0.25% to 4.75–5.0% and launches the Bank Term Funding Program, which will aid distressed banks suffering from interest-rate risk

- May 4, 2023: The Fed hikes another 0.25% to 5.00–5.25%

- July 27, 2023: The Fed delivers its final 0.25% increase of 2023, bringing rates to 5.25–5.50%

Government

The Grinch Who Stole Freedom

The Grinch Who Stole Freedom

Authored by Jeffrey A. Tucker via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

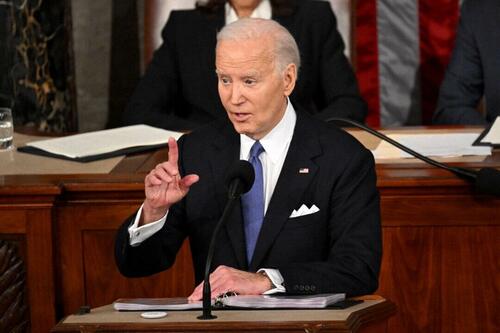

Before President Joe Biden’s State of the…

Authored by Jeffrey A. Tucker via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Before President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address, the pundit class was predicting that he would deliver a message of unity and calm, if only to attract undecided voters to his side.

He did the opposite. The speech revealed a loud, cranky, angry, bitter side of the man that people don’t usually see. It seemed like the real Joe Biden I remember from the old days, full of venom, sarcasm, disdain, threats, and extreme partisanship.

The base might have loved it except that he made reference to an “illegal” alien, which is apparently a trigger word for the left. He failed their purity test.

The speech was stunning in its bile and bitterness. It’s beyond belief that he began with a pitch for more funds for the Ukraine war, which has killed 10,000 civilians and some 200,000 troops on both sides. It’s a bloody mess that could have been resolved early on but for U.S. tax funding of the conflict.

Despite the push from the higher ends of conservative commentary, average Republicans have turned hard against this war. The United States is in a fiscal crisis and every manner of domestic crisis, and the U.S. president opens his speech with a pitch to protect the border in Ukraine? It was completely bizarre, and lent some weight to the darkest conspiracies about why the Biden administration cares so much about this issue.

From there, he pivoted to wildly overblown rhetoric about the most hysterically exaggerated event of our times: the legendary Jan. 6 protests on Capitol Hill. Arrests for daring to protest the government on that day are growing.

The media and the Biden administration continue to describe it as the worst crisis since the War of the Roses, or something. It’s all a wild stretch, but it set the tone of the whole speech, complete with unrelenting attacks on former President Donald Trump. He would use the speech not to unite or make a pitch that he is president of the entire country but rather intensify his fundamental attack on everything America is supposed to be.

Hard to isolate the most alarming part, but one aspect really stood out to me. He glared directly at the Supreme Court Justices sitting there and threatened them with political power. He said that they were awful for getting rid of nationwide abortion rights and returning the issue to the states where it belongs, very obviously. But President Biden whipped up his base to exact some kind of retribution against the court.

Looking this up, we have a few historical examples of presidents criticizing the court but none to their faces in a State of the Union address. This comes two weeks after President Biden directly bragged about defying the Supreme Court over the issue of student loan forgiveness. The court said he could not do this on his own, but President Biden did it anyway.

Here we have an issue of civic decorum that you cannot legislate or legally codify. Essentially, under the U.S. system, the president has to agree to defer to the highest court in its rulings even if he doesn’t like them. President Biden is now aggressively defying the court and adding direct threats on top of that. In other words, this president is plunging us straight into lawlessness and dictatorship.

In the background here, you must understand, is the most important free speech case in U.S. history. The Supreme Court on March 18 will hear arguments over an injunction against President Biden’s administrative agencies as issued by the Fifth Circuit. The injunction would forbid government agencies from imposing themselves on media and social media companies to curate content and censor contrary opinions, either directly or indirectly through so-called “switchboarding.”

A ruling for the plaintiffs in the case would force the dismantling of a growing and massive industry that has come to be called the censorship-industrial complex. It involves dozens or even more than 100 government agencies, including quasi-intelligence agencies such as the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which was set up only in 2018 but managed information flow, labor force designations, and absentee voting during the COVID-19 response.

A good ruling here will protect free speech or at least intend to. But, of course, the Biden administration could directly defy it. That seems to be where this administration is headed. It’s extremely dangerous.

A ruling for the defense and against the injunction would be a catastrophe. It would invite every government agency to exercise direct control over all media and social media in the country, effectively abolishing the First Amendment.

Close watchers of the court have no clear idea of how this will turn out. But watching President Biden glare at court members at the address, one does wonder. Did they sense the threats he was making against them? Will they stand up for the independence of the judicial branch?

Maybe his intimidation tactics will end up backfiring. After all, does the Supreme Court really think it is wise to license this administration with the power to control all information flows in the United States?

The deeper issue here is a pressing battle that is roiling American life today. It concerns the future and power of the administrative state versus the elected one. The Constitution contains no reference to a fourth branch of government, but that is what has been allowed to form and entrench itself, in complete violation of the Founders’ intentions. Only the Supreme Court can stop it, if they are brave enough to take it on.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, and surely you have, President Biden is nothing but a marionette of deep-state interests. He is there to pretend to be the people’s representative, but everything that he does is about entrenching the fourth branch of government, the permanent bureaucracy that goes on its merry way without any real civilian oversight.

We know this for a fact by virtue of one of his first acts as president, to repeal an executive order by President Trump that would have reclassified some (or many) federal employees as directly under the control of the elected president rather than have independent power. The elites in Washington absolutely panicked about President Trump’s executive order. They plotted to make sure that he didn’t get a second term, and quickly scratched that brilliant act by President Trump from the historical record.

This epic battle is the subtext behind nearly everything taking place in Washington today.

Aside from the vicious moment of directly attacking the Supreme Court, President Biden set himself up as some kind of economic central planner, promising to abolish hidden fees and bags of chips that weren’t full enough, as if he has the power to do this, which he does not. He was up there just muttering gibberish. If he is serious, he believes that the U.S. president has the power to dictate the prices of every candy bar and hotel room in the United States—an absolutely terrifying exercise of power that compares only to Stalin and Mao. And yet there he was promising to do just that.

Aside from demonizing the opposition, wildly exaggerating about Jan. 6, whipping up war frenzy, swearing to end climate change, which will make the “green energy” industry rich, threatening more taxes on business enterprise, promising to cure cancer (again!), and parading as the master of candy bar prices, what else did he do? Well, he took credit for the supposedly growing economy even as a vast number of Americans are deeply suffering from his awful policies.

It’s hard to imagine that this speech could be considered a success. The optics alone made him look like the Grinch who stole freedom, except the Grinch was far more articulate and clever. He’s a mean one, Mr. Biden.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

International

Chinese migration to US is nothing new – but the reasons for recent surge at Southern border are

A gloomier economic outlook in China and tightening state control have combined with the influence of social media in encouraging migration.

The brief closure of the Darien Gap – a perilous 66-mile jungle journey linking South American and Central America – in February 2024 temporarily halted one of the Western Hemisphere’s busiest migration routes. It also highlighted its importance to a small but growing group of people that depend on that pass to make it to the U.S.: Chinese migrants.

While a record 2.5 million migrants were detained at the United States’ southwestern land border in 2023, only about 37,000 were from China.

I’m a scholar of migration and China. What I find most remarkable in these figures is the speed with which the number of Chinese migrants is growing. Nearly 10 times as many Chinese migrants crossed the southern border in 2023 as in 2022. In December 2023 alone, U.S. Border Patrol officials reported encounters with about 6,000 Chinese migrants, in contrast to the 900 they reported a year earlier in December 2022.

The dramatic uptick is the result of a confluence of factors that range from a slowing Chinese economy and tightening political control by President Xi Jinping to the easy access to online information on Chinese social media about how to make the trip.

Middle-class migrants

Journalists reporting from the border have generalized that Chinese migrants come largely from the self-employed middle class. They are not rich enough to use education or work opportunities as a means of entry, but they can afford to fly across the world.

According to a report from Reuters, in many cases those attempting to make the crossing are small-business owners who saw irreparable damage to their primary or sole source of income due to China’s “zero COVID” policies. The migrants are women, men and, in some cases, children accompanying parents from all over China.

Chinese nationals have long made the journey to the United States seeking economic opportunity or political freedom. Based on recent media interviews with migrants coming by way of South America and the U.S.’s southern border, the increase in numbers seems driven by two factors.

First, the most common path for immigration for Chinese nationals is through a student visa or H1-B visa for skilled workers. But travel restrictions during the early months of the pandemic temporarily stalled migration from China. Immigrant visas are out of reach for many Chinese nationals without family or vocation-based preferences, and tourist visas require a personal interview with a U.S. consulate to gauge the likelihood of the traveler returning to China.

Social media tutorials

Second, with the legal routes for immigration difficult to follow, social media accounts have outlined alternatives for Chinese who feel an urgent need to emigrate. Accounts on Douyin, the TikTok clone available in mainland China, document locations open for visa-free travel by Chinese passport holders. On TikTok itself, migrants could find information on where to cross the border, as well as information about transportation and smugglers, commonly known as “snakeheads,” who are experienced with bringing migrants on the journey north.

With virtual private networks, immigrants can also gather information from U.S. apps such as X, YouTube, Facebook and other sites that are otherwise blocked by Chinese censors.

Inspired by social media posts that both offer practical guides and celebrate the journey, thousands of Chinese migrants have been flying to Ecuador, which allows visa-free travel for Chinese citizens, and then making their way over land to the U.S.-Mexican border.

This journey involves trekking through the Darien Gap, which despite its notoriety as a dangerous crossing has become an increasingly common route for migrants from Venezuela, Colombia and all over the world.

In addition to information about crossing the Darien Gap, these social media posts highlight the best places to cross the border. This has led to a large share of Chinese asylum seekers following the same path to Mexico’s Baja California to cross the border near San Diego.

Chinese migration to US is nothing new

The rapid increase in numbers and the ease of accessing information via social media on their smartphones are new innovations. But there is a longer history of Chinese migration to the U.S. over the southern border – and at the hands of smugglers.

From 1882 to 1943, the United States banned all immigration by male Chinese laborers and most Chinese women. A combination of economic competition and racist concerns about Chinese culture and assimilability ensured that the Chinese would be the first ethnic group to enter the United States illegally.

With legal options for arrival eliminated, some Chinese migrants took advantage of the relative ease of movement between the U.S. and Mexico during those years. While some migrants adopted Mexican names and spoke enough Spanish to pass as migrant workers, others used borrowed identities or paperwork from Chinese people with a right of entry, like U.S.-born citizens. Similarly to what we are seeing today, it was middle- and working-class Chinese who more frequently turned to illegal means. Those with money and education were able to circumvent the law by arriving as students or members of the merchant class, both exceptions to the exclusion law.

Though these Chinese exclusion laws officially ended in 1943, restrictions on migration from Asia continued until Congress revised U.S. immigration law in the Hart-Celler Act in 1965. New priorities for immigrant visas that stressed vocational skills as well as family reunification, alongside then Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s policies of “reform and opening,” helped many Chinese migrants make their way legally to the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s.

Even after the restrictive immigration laws ended, Chinese migrants without the education or family connections often needed for U.S. visas continued to take dangerous routes with the help of “snakeheads.”

One notorious incident occurred in 1993, when a ship called the Golden Venture ran aground near New York, resulting in the drowning deaths of 10 Chinese migrants and the arrest and conviction of the snakeheads attempting to smuggle hundreds of Chinese migrants into the United States.

Existing tensions

Though there is plenty of precedent for Chinese migrants arriving without documentation, Chinese asylum seekers have better odds of success than many of the other migrants making the dangerous journey north.

An estimated 55% of Chinese asylum seekers are successful in making their claims, often citing political oppression and lack of religious freedom in China as motivations. By contrast, only 29% of Venezuelans seeking asylum in the U.S. have their claim granted, and the number is even lower for Colombians, at 19%.

The new halt on the migratory highway from the south has affected thousands of new migrants seeking refuge in the U.S. But the mix of push factors from their home country and encouragement on social media means that Chinese migrants will continue to seek routes to America.

And with both migration and the perceived threat from China likely to be features of the upcoming U.S. election, there is a risk that increased Chinese migration could become politicized, leaning further into existing tensions between Washington and Beijing.

Meredith Oyen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

congress pandemic deaths south america mexico chinaGovernment

Is the National Guard a solution to school violence?

School board members in one Massachusetts district have called for the National Guard to address student misbehavior. Does their request have merit? A…

Every now and then, an elected official will suggest bringing in the National Guard to deal with violence that seems out of control.

A city council member in Washington suggested doing so in 2023 to combat the city’s rising violence. So did a Pennsylvania representative concerned about violence in Philadelphia in 2022.

In February 2024, officials in Massachusetts requested the National Guard be deployed to a more unexpected location – to a high school.

Brockton High School has been struggling with student fights, drug use and disrespect toward staff. One school staffer said she was trampled by a crowd rushing to see a fight. Many teachers call in sick to work each day, leaving the school understaffed.

As a researcher who studies school discipline, I know Brockton’s situation is part of a national trend of principals and teachers who have been struggling to deal with perceived increases in student misbehavior since the pandemic.

A review of how the National Guard has been deployed to schools in the past shows the guard can provide service to schools in cases of exceptional need. Yet, doing so does not always end well.

How have schools used the National Guard before?

In 1957, the National Guard blocked nine Black students’ attempts to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. While the governor claimed this was for safety, the National Guard effectively delayed desegregation of the school – as did the mobs of white individuals outside. Ironically, weeks later, the National Guard and the U.S. Army would enforce integration and the safety of the “Little Rock Nine” on orders from President Dwight Eisenhower.

One of the most tragic cases of the National Guard in an educational setting came in 1970 at Kent State University. The National Guard was brought to campus to respond to protests over American involvement in the Vietnam War. The guardsmen fatally shot four students.

In 2012, then-Sen. Barbara Boxer, a Democrat from California, proposed funding to use the National Guard to provide school security in the wake of the Sandy Hook school shooting. The bill was not passed.

More recently, the National Guard filled teacher shortages in New Mexico’s K-12 schools during the quarantines and sickness of the pandemic. While the idea did not catch on nationally, teachers and school personnel in New Mexico generally reported positive experiences.

Can the National Guard address school discipline?

The National Guard’s mission includes responding to domestic emergencies. Members of the guard are part-time service members who maintain civilian lives. Some are students themselves in colleges and universities. Does this mission and training position the National Guard to respond to incidents of student misbehavior and school violence?

On the one hand, New Mexico’s pandemic experience shows the National Guard could be a stopgap to staffing shortages in unusual circumstances. Similarly, the guards’ eventual role in ensuring student safety during school desegregation in Arkansas demonstrates their potential to address exceptional cases in schools, such as racially motivated mob violence. And, of course, many schools have had military personnel teaching and mentoring through Junior ROTC programs for years.

Those seeking to bring the National Guard to Brockton High School have made similar arguments. They note that staffing shortages have contributed to behavior problems.

One school board member stated: “I know that the first thought that comes to mind when you hear ‘National Guard’ is uniform and arms, and that’s not the case. They’re people like us. They’re educated. They’re trained, and we just need their assistance right now. … We need more staff to support our staff and help the students learn (and) have a safe environment.”

Yet, there are reasons to question whether calls for the National Guard are the best way to address school misconduct and behavior. First, the National Guard is a temporary measure that does little to address the underlying causes of student misbehavior and school violence.

Research has shown that students benefit from effective teaching, meaningful and sustained relationships with school personnel and positive school environments. Such educative and supportive environments have been linked to safer schools. National Guard members are not trained as educators or counselors and, as a temporary measure, would not remain in the school to establish durable relationships with students.

What is more, a military presence – particularly if uniformed or armed – may make students feel less welcome at school or escalate situations.

Schools have already seen an increase in militarization. For example, school police departments have gone so far as to acquire grenade launchers and mine-resistant armored vehicles.

Research has found that school police make students more likely to be suspended and to be arrested. Similarly, while a National Guard presence may address misbehavior temporarily, their presence could similarly result in students experiencing punitive or exclusionary responses to behavior.

Students deserve a solution other than the guard

School violence and disruptions are serious problems that can harm students. Unfortunately, schools and educators have increasingly viewed student misbehavior as a problem to be dealt with through suspensions and police involvement.

A number of people – from the NAACP to the local mayor and other members of the school board – have criticized Brockton’s request for the National Guard. Governor Maura Healey has said she will not deploy the guard to the school.

However, the case of Brockton High School points to real needs. Educators there, like in other schools nationally, are facing a tough situation and perceive a lack of support and resources.

Many schools need more teachers and staff. Students need access to mentors and counselors. With these resources, schools can better ensure educators are able to do their jobs without military intervention.

F. Chris Curran has received funding from the US Department of Justice, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the American Civil Liberties Union for work on school safety and discipline.

army governor pandemic mexico-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex