State policy solutions for good home health care jobs—nearly half held by Black women in the South—should address the legacy of racism, sexism, and xenophobia in the workforce

Home health care workers are part of the “care economy” that makes all other work These workers include nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides;…

Introduction

Home health care workers are part of the “care economy” that makes all other work possible.

These workers include nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides; personal and home care aides; and nursing assistants working in private households. They provide services and support for older adults, people with chronic illnesses, and people with disabilities allowing them to stay in their homes and communities, rather than nursing homes or other institutions. And the COVID-19 public health emergency further highlighted the importance of this workforce, who provide long-term care at a time when congregate settings are limited in their ability to support physical distancing or quarantining.

So why don’t we value these workers?

The underappreciation of care jobs historically and today reflects the prevailing legacy of racism, sexism, and xenophobia. Black women are vastly overrepresented among home health care workers, especially in the Southern United States, where these workers are paid the least. (Louisiana, West Virginia, Texas, Mississippi, and Oklahoma).

There is a disproportionate representation of Black, Latinx, and immigrant women in the Southern home health care workforce and there is an eye-opening history of how Black women in the South became the single largest group of workers in these jobs.

Home health care workers, who make up a substantial share of the larger domestic worker job classification, have long been coming together for fair wages and working conditions. The current policy climate in the South needs an overhaul and there are opportunities for state policymakers to support good jobs for home health care workers.

Demographic Profile of Home Health Care Workers

Home health care work is both highly racialized and gendered, especially in the South. As shown in Figures A and B, Black and Latinx women are overrepresented in the home health care workforce compared to the overall labor force. While Black women make up 11% of all workers in the South, they account for a remarkable 43% of home health care workers, nearly four times their share in the labor force. Similarly, Latinx women account for an estimated 7% of the Southern labor force, yet they make up more than twice that share among home health care workers at 17%. White women in the South are proportionately represented in the home health care work force relative to their share in the overall Southern labor force.

Similar patterns exist when we look at citizenship status. Here, the term U.S.-born women refers to women who were born in the U.S. or were U.S. citizens at birth, and naturalized citizen women are women who are currently U.S. citizens but were not citizens at birth. We use the term “immigrant women” to refer to both naturalized U.S. citizens and non-citizen women, i.e., women who were not U.S. citizens at time of birth. Due to small sample size concerns, we combine Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) women and women of other races, and do not report statistics for the Midwest.

As shown in Figure C, in the South, immigrant women make up about 6% of the Southern workforce, but they account for approximately 18% of home health care workers – nearly three times their share of the overall workforce. Across the country, immigrant women are overrepresented among home health care workers, although their smaller share of the overall population in the South means they make up a much smaller share of the home healthcare workforce there.

The demographic makeup of this workforce is a crucial factor in the devaluation of the work they do. We can see this across a range of occupations—when workers are primarily women and Black and Brown people, wages tend to be lower.

Current vs. Better Wages for Southern Home Health Care Workers

In a previous report, we laid out arguments and mechanisms for increasing home health care workers’ wages at the state level. We estimated better wages that we compared with the current wages for home health workers. Figure D and Table 1 (in the appendix) contain the relevant data for states in the South plus the District of Columbia. As detailed in our report, the five states with the lowest estimated current wages for home health care workers are all in the South (namely, Louisiana, West Virginia, Texas, Mississippi, and Oklahoma). In these states, home health care workers typically make less than $12 an hour, compared to the national average of about $13.50.

Further, even after we adjust for regional differences in cost of living, Southern states still tend to have the largest gaps between current care worker wage rates and rates that would better value care work. At the national level, the average home health care wage is about $8.70 less than our proposed wage benchmark. As shown in Figure D and appendix Table 1, only 3 states in the South have gaps smaller than this national average (Arkansas, Mississippi, and West Virginia).

Why Home Health Care Workers Experience Low Wages: The Ongoing Influence of Racism and Sexism

The current demographic makeup of the home health care workforce in the South is not accidental, and neither is the low pay, lack of benefits, or lack of worker protections. These are noted in the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow. The work that home health care workers do has historically been unpaid work that women provided in the home or, especially in Southern states, enslaved Black women provided. Later, free Black and Latinx women performed this work. Because of who did the work, it was seen as unskilled work and therefore devalued. Black women remained tied to these roles through Jim Crow practices that largely limited all other economic opportunities. For example, in 1940 over three-quarters of Black women were employed as either domestic workers in private homes or as agricultural laborers.

The particularly poor quality of these jobs was maintained by the federal government, which excluded these workers from major federal labor legislation as a concession to Southern White lawmakers. These laws include the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935, which was intended to ensure that workers could form unions and use collective bargaining to get fair working conditions, and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which set the minimum wage workers could be paid and established requirements for overtime compensation. These laws were intended to empower workers, protect them from the exploitative behavior of employers, and ensure they have a reasonable standard of living. Federal lawmakers, however, excluded domestic workers and agricultural workers from these protections. The long history of tying Black, Latinx, and immigrant women to these jobs has reinforced harmful racial narratives, one of many ways the racial hierarchy that is so central to Southern social, cultural, and economic systems is maintained.

Domestic Workers Unite to Organize

Despite the devaluation of their work and their exclusion from important worker protections, domestic workers, including home health care workers, have historically fought and continue to fight to improve the quality of their jobs. In 1881, laundry workers in Atlanta, primarily Black women, formed the Washing Society, a trade organization which successful secured higher wages after 3,000 workers agreed to strike. Also, in Atlanta in the 1960s, Dorothy Bolden founded the National Domestic Workers Union of America, organizing 10,000 domestic workers to win increases in pay and workplace protections. Today, many unions and national and local grassroots organizations continue to organize with home health care workers and other domestic workers around the country and in the South. By organizing, domestic workers are building political power and working with policymakers to enact policies for family-sustaining wages and benefits and long-term careers in the industry.

How State Policymakers in the South Can Support Home Health Care Workers

There are many tools available to policymakers to increase pay and benefits for home health care workers. While much more is needed, there is movement in Southern states and around the country to invest in long-term care services and strengthen the home health care workforce. These tools include federal relief and recovery dollars provided during the COVID-19 public health emergency, state legislation, and partnerships with state agencies.

Federal Relief and Recovery Dollars Allocated to States

Southern states utilized previous federal relief and recovery dollars from the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act to increase wages and provide paid leave for home health care workers, primarily through temporary benefits and wage increases or one-time bonuses to support recruitment and retention.

Subsequently, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allocated $12.7 billion for states to strengthen and expand access to home and community based services (HCBS). Home and community-based services (HCBS) enable people, particularly older adults and people with disabilities eligible for Medicaid, to receive long-term care in their own homes and communities.

States can utilize a temporary 10% increase in their federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) to expand eligibility and increase access to HCBS while also strengthening the home health care workforce by increasing the pay and benefits of direct care workers.

States using these funds are required to invest in HCBS without supplanting existing state funds for Medicaid HCBS, imposing stricter eligibility standards, reducing the scope and duration of services, or reducing the provider payment rates that could further erode workers’ wages.

Many states in the South—including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia—committed to using federal funds to invest in HCBS. Several of these states are likely to increase wages for home health care workers, as noted in their state spending plans. States may increase direct care worker wages by increasing HCBS provider rates, while also requiring that the majority of these funds are used to increase workers’ wages or by setting a wage floor. Without proper support and implementation for requiring increase in wages, workers may never see the benefits of these efforts, as in North Carolina.

The need for states to leverage these resources, which after a recent extension may now be used through March 31, 2025, is particularly large as efforts to make this funding permanent through the passage of the Build Back Better Act have stalled.

State Legislation

Ultimately, in the absence of federal interventions, permanent state policy solutions are needed to provide stability for workers providing care and people receiving these critical services. State policymakers have many tools available to them to increase pay and benefits and to support a voice on the job for home health care workers. Virginia offers a particularly good example. Previously enacted legislation to gradually increase Virginia’s minimum wage to $15 by 2026 guarantees minimum wage protections for domestic workers for the first time—in many states, domestic workers are exempt from minimum wage protections. Virginia now also guarantees paid leave to home health care workers in the state, who will now accrue one hour of paid leave for every 30 hours of work. In 2021, Virginia also became the first state in the South to pass a Domestic Worker’s Bill of Rights, joining nine other states and two other cities around the country.

Home Care Authorities

Models from elsewhere in the country offer additional strategies for improving job quality for home health care workers. For example, some domestic workers have been able to establish a local or state government entity as their employer for the purposes of collective bargaining, allowing them to negotiate collectively for better wages and working conditions. In California, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) built a coalition including home health care workers, the disability rights community, and advocates for the elderly and advocated for the creation of home care authorities at the county level, with whom home health care workers can collectively bargain. This model has been replicated in other states (Connecticut, Oregon, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Washington) with state-level authorities. Home care workers in these states have earnings higher than home care workers nationally and they have been able to negotiate other benefits, including healthcare and retirement benefits.

Conclusion

More action by state policymakers is needed to support home health care workers and address systemic inequities experienced by this predominantly Black, Latinx, and immigrant workforce. This is especially the case in the South where Black women workers are overrepresented, making up nearly half of the workforce while receiving the lowest wages relative to home care workers in other parts of the country. This is part of a long history of economic exclusion based on race and gender and why care workers continue to organize for fair wages, benefits, and workplace protections. State policymakers should utilize recent federal relief and recovery dollars, partner with state agencies, and develop legislative vehicles for longer-term policy solutions to improve financing for long-term care services, while also ensuring that care jobs are good jobs.

Uncategorized

Key shipping company files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy

The Illinois-based general freight trucking company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy to reorganize.

The U.S. trucking industry has had a difficult beginning of the year for 2024 with several logistics companies filing for bankruptcy to seek either a Chapter 7 liquidation or Chapter 11 reorganization.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a lot of supply chain issues for logistics companies and also created a shortage of truck drivers as many left the business for other occupations. Shipping companies, in the meantime, have had extreme difficulty recruiting new drivers for thousands of unfilled jobs.

Related: Tesla rival’s filing reveals Chapter 11 bankruptcy is possible

Freight forwarder company Boateng Logistics joined a growing list of shipping companies that permanently shuttered their businesses as the firm on Feb. 22 filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy with plans to liquidate.

The Carlsbad, Calif., logistics company filed its petition in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of California listing assets up to $50,000 and and $1 million to $10 million in liabilities. Court papers said it owed millions of dollars in liabilities to trucking, logistics and factoring companies. The company filed bankruptcy before any creditors could take legal action.

Lawsuits force companies to liquidate in bankruptcy

Lawsuits, however, can force companies to file bankruptcy, which was the case for J.J. & Sons Logistics of Clint, Texas, which on Jan. 22 filed for Chapter 7 liquidation in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Texas. The company filed bankruptcy four days before the scheduled start of a trial for a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of a former company truck driver who had died from drowning in 2016.

California-based logistics company Wise Choice Trans Corp. shut down operations and filed for Chapter 7 liquidation on Jan. 4 in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of California, listing $1 million to $10 million in assets and liabilities.

The Hayward, Calif., third-party logistics company, founded in 2009, provided final mile, less-than-truckload and full truckload services, as well as warehouse and fulfillment services in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Chapter 7 filing also implemented an automatic stay against all legal proceedings, as the company listed its involvement in four legal actions that were ongoing or concluded. Court papers reportedly did not list amounts for damages.

In some cases, debtors don't have to take a drastic action, such as a liquidation, and can instead file a Chapter 11 reorganization.

Shutterstock

Nationwide Cargo seeks to reorganize its business

Nationwide Cargo Inc., a general freight trucking company that also hauls fresh produce and meat, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Illinois with plans to reorganize its business.

The East Dundee, Ill., shipping company listed $1 million to $10 million in assets and $10 million to $50 million in liabilities in its petition and said funds will not be available to pay unsecured creditors. The company operates with 183 trucks and 171 drivers, FreightWaves reported.

Nationwide Cargo's three largest secured creditors in the petition were Equify Financial LLC (owed about $3.5 million,) Commercial Credit Group (owed about $1.8 million) and Continental Bank NA (owed about $676,000.)

The shipping company reported gross revenue of about $34 million in 2022 and about $40 million in 2023. From Jan. 1 until its petition date, the company generated $9.3 million in gross revenue.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

bankruptcy pandemic covid-19 stocksUncategorized

Key shipping company files Chapter 11 bankruptcy

The Illinois-based general freight trucking company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy to reorganize.

The U.S. trucking industry has had a difficult beginning of the year for 2024 with several logistics companies filing for bankruptcy to seek either a Chapter 7 liquidation or Chapter 11 reorganization.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a lot of supply chain issues for logistics companies and also created a shortage of truck drivers as many left the business for other occupations. Shipping companies, in the meantime, have had extreme difficulty recruiting new drivers for thousands of unfilled jobs.

Related: Tesla rival’s filing reveals Chapter 11 bankruptcy is possible

Freight forwarder company Boateng Logistics joined a growing list of shipping companies that permanently shuttered their businesses as the firm on Feb. 22 filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy with plans to liquidate.

The Carlsbad, Calif., logistics company filed its petition in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of California listing assets up to $50,000 and and $1 million to $10 million in liabilities. Court papers said it owed millions of dollars in liabilities to trucking, logistics and factoring companies. The company filed bankruptcy before any creditors could take legal action.

Lawsuits force companies to liquidate in bankruptcy

Lawsuits, however, can force companies to file bankruptcy, which was the case for J.J. & Sons Logistics of Clint, Texas, which on Jan. 22 filed for Chapter 7 liquidation in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Texas. The company filed bankruptcy four days before the scheduled start of a trial for a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of a former company truck driver who had died from drowning in 2016.

California-based logistics company Wise Choice Trans Corp. shut down operations and filed for Chapter 7 liquidation on Jan. 4 in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of California, listing $1 million to $10 million in assets and liabilities.

The Hayward, Calif., third-party logistics company, founded in 2009, provided final mile, less-than-truckload and full truckload services, as well as warehouse and fulfillment services in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Chapter 7 filing also implemented an automatic stay against all legal proceedings, as the company listed its involvement in four legal actions that were ongoing or concluded. Court papers reportedly did not list amounts for damages.

In some cases, debtors don't have to take a drastic action, such as a liquidation, and can instead file a Chapter 11 reorganization.

Shutterstock

Nationwide Cargo seeks to reorganize its business

Nationwide Cargo Inc., a general freight trucking company that also hauls fresh produce and meat, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Illinois with plans to reorganize its business.

The East Dundee, Ill., shipping company listed $1 million to $10 million in assets and $10 million to $50 million in liabilities in its petition and said funds will not be available to pay unsecured creditors. The company operates with 183 trucks and 171 drivers, FreightWaves reported.

Nationwide Cargo's three largest secured creditors in the petition were Equify Financial LLC (owed about $3.5 million,) Commercial Credit Group (owed about $1.8 million) and Continental Bank NA (owed about $676,000.)

The shipping company reported gross revenue of about $34 million in 2022 and about $40 million in 2023. From Jan. 1 until its petition date, the company generated $9.3 million in gross revenue.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

bankruptcy pandemic covid-19 stocksUncategorized

Tight inventory and frustrated buyers challenge agents in Virginia

With inventory a little more than half of what it was pre-pandemic, agents are struggling to find homes for clients in Virginia.

No matter where you are in the state, real estate agents in Virginia are facing low inventory conditions that are creating frustrating scenarios for their buyers.

“I think people are getting used to the interest rates where they are now, but there is just a huge lack of inventory,” said Chelsea Newcomb, a RE/MAX Realty Specialists agent based in Charlottesville. “I have buyers that are looking, but to find a house that you love enough to pay a high price for — and to be at over a 6.5% interest rate — it’s just a little bit harder to find something.”

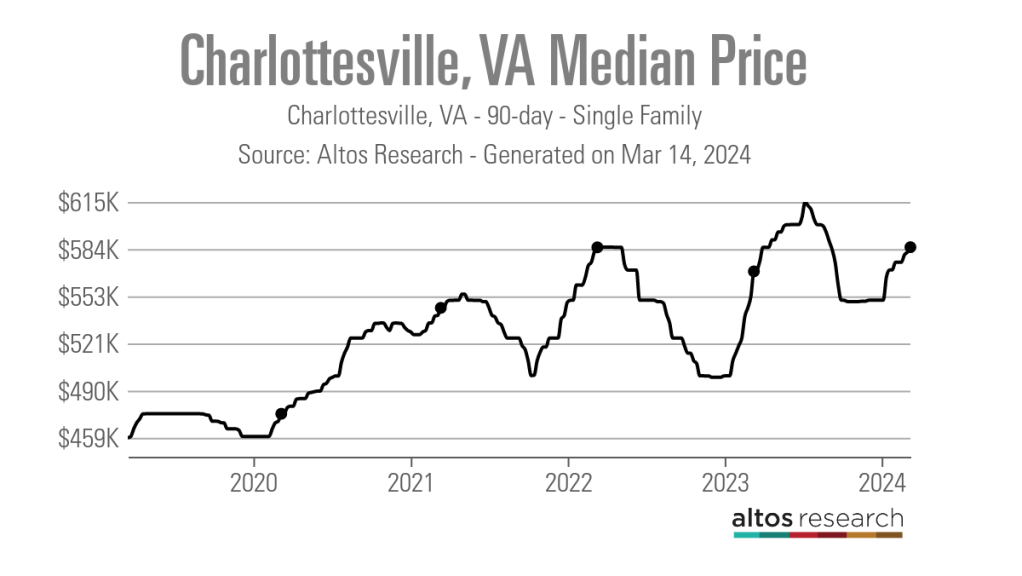

Newcomb said that interest rates and higher prices, which have risen by more than $100,000 since March 2020, according to data from Altos Research, have caused her clients to be pickier when selecting a home.

“When rates and prices were lower, people were more willing to compromise,” Newcomb said.

Out in Wise, Virginia, near the westernmost tip of the state, RE/MAX Cavaliers agent Brett Tiller and his clients are also struggling to find suitable properties.

“The thing that really stands out, especially compared to two years ago, is the lack of quality listings,” Tiller said. “The slightly more upscale single-family listings for move-up buyers with children looking for their forever home just aren’t coming on the market right now, and demand is still very high.”

Statewide, Virginia had a 90-day average of 8,068 active single-family listings as of March 8, 2024, down from 14,471 single-family listings in early March 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Altos Research. That represents a decrease of 44%.

In Newcomb’s base metro area of Charlottesville, there were an average of only 277 active single-family listings during the same recent 90-day period, compared to 892 at the onset of the pandemic. In Wise County, there were only 56 listings.

Due to the demand from move-up buyers in Tiller’s area, the average days on market for homes with a median price of roughly $190,000 was just 17 days as of early March 2024.

“For the right home, which is rare to find right now, we are still seeing multiple offers,” Tiller said. “The demand is the same right now as it was during the heart of the pandemic.”

According to Tiller, the tight inventory has caused homebuyers to spend up to six months searching for their new property, roughly double the time it took prior to the pandemic.

For Matt Salway in the Virginia Beach metro area, the tight inventory conditions are creating a rather hot market.

“Depending on where you are in the area, your listing could have 15 offers in two days,” the agent for Iron Valley Real Estate Hampton Roads | Virginia Beach said. “It has been crazy competition for most of Virginia Beach, and Norfolk is pretty hot too, especially for anything under $400,000.”

According to Altos Research, the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News housing market had a seven-day average Market Action Index score of 52.44 as of March 14, making it the seventh hottest housing market in the country. Altos considers any Market Action Index score above 30 to be indicative of a seller’s market.

Further up the coastline on the vacation destination of Chincoteague Island, Long & Foster agent Meghan O. Clarkson is also seeing a decent amount of competition despite higher prices and interest rates.

“People are taking their time to actually come see things now instead of buying site unseen, and occasionally we see some seller concessions, but the traffic and the demand is still there; you might just work a little longer with people because we don’t have anything for sale,” Clarkson said.

“I’m busy and constantly have appointments, but the underlying frenzy from the height of the pandemic has gone away, but I think it is because we have just gotten used to it.”

While much of the demand that Clarkson’s market faces is for vacation homes and from retirees looking for a scenic spot to retire, a large portion of the demand in Salway’s market comes from military personnel and civilians working under government contracts.

“We have over a dozen military bases here, plus a bunch of shipyards, so the closer you get to all of those bases, the easier it is to sell a home and the faster the sale happens,” Salway said.

Due to this, Salway said that existing-home inventory typically does not come on the market unless an employment contract ends or the owner is reassigned to a different base, which is currently contributing to the tight inventory situation in his market.

Things are a bit different for Tiller and Newcomb, who are seeing a decent number of buyers from other, more expensive parts of the state.

“One of the crazy things about Louisa and Goochland, which are kind of like suburbs on the western side of Richmond, is that they are growing like crazy,” Newcomb said. “A lot of people are coming in from Northern Virginia because they can work remotely now.”

With a Market Action Index score of 50, it is easy to see why people are leaving the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria market for the Charlottesville market, which has an index score of 41.

In addition, the 90-day average median list price in Charlottesville is $585,000 compared to $729,900 in the D.C. area, which Newcomb said is also luring many Virginia homebuyers to move further south.

“They are very accustomed to higher prices, so they are super impressed with the prices we offer here in the central Virginia area,” Newcomb said.

For local buyers, Newcomb said this means they are frequently being outbid or outpriced.

“A couple who is local to the area and has been here their whole life, they are just now starting to get their mind wrapped around the fact that you can’t get a house for $200,000 anymore,” Newcomb said.

As the year heads closer to spring, triggering the start of the prime homebuying season, agents in Virginia feel optimistic about the market.

“We are seeing seasonal trends like we did up through 2019,” Clarkson said. “The market kind of soft launched around President’s Day and it is still building, but I expect it to pick right back up and be in full swing by Easter like it always used to.”

But while they are confident in demand, questions still remain about whether there will be enough inventory to support even more homebuyers entering the market.

“I have a lot of buyers starting to come off the sidelines, but in my office, I also have a lot of people who are going to list their house in the next two to three weeks now that the weather is starting to break,” Newcomb said. “I think we are going to have a good spring and summer.”

real estate housing market pandemic covid-19 interest rates-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International7 days ago

International7 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International7 days ago

International7 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges