Uncategorized

S&P Global Mobility Special Report: US Automotive Market Share Wars will Resume in 2023

S&P Global Mobility Special Report: US Automotive Market Share Wars will Resume in 2023

PR Newswire

SOUTHFIELD, Mich., Feb. 2, 2023

Recovering inventories are increasing dealer stock, while interest rate hikes and economic headwinds will dampen…

S&P Global Mobility Special Report: US Automotive Market Share Wars will Resume in 2023

PR Newswire

SOUTHFIELD, Mich., Feb. 2, 2023

Recovering inventories are increasing dealer stock, while interest rate hikes and economic headwinds will dampen demand – forcing OEMs and dealers to make deals once again. The question is: Who will blink first?

SOUTHFIELD, Mich., Feb. 2, 2023 /PRNewswire/ -- After nearly two years of inflated new- and used-car prices – with car dealers asking consumers to pay thousands of dollars over MSRP – the US industry is primed for a reset to previous competitive norms.

A combination of industry factors and macroeconomic conditions could trigger a potentially bloody battle for market share this year, according to an analysis by S&P Global Mobility. Automakers and dealers that have grown accustomed to huge profits on vehicles sold as soon as they leave the factory will see a return to traditional conditions of accumulating showroom inventories and the need for incentives to move the metal.

This could mean a big win for consumers still in the market for a new or used vehicle, and who are not intimidated by sharply increased lending rates or other economic headwinds. Already there are signs of increased new-car inventories and declining used-car prices – though not yet to pre-COVID levels.

"Things will heat up this year when the first tranche of COVID-sold vehicles starts returning to market," predicts Dave Mondragon, vice president of product development for S&P Global Mobility. "These vehicles are all underwater. They were sold at record-high prices with no discounts, and there will be little to no equity to roll into a new vehicle."

It's not so much the volume of vehicles coming back – new-vehicle sales cratered in 2020 when production lines slowed due to supply chain snarls. But the practice by many dealerships of using vehicle shortages to sell at inflated prices means nearly every vehicle coming back has massive negative equity – with the customer owing thousands of dollars more than the vehicle is worth at trade-in. "That's when discounting starts up again," Mondragon says.

Inventory Rebounding

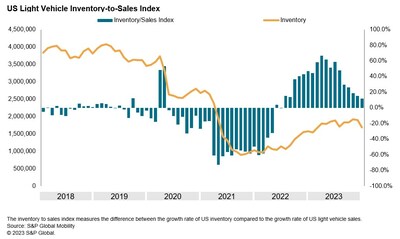

With supply chain snarls easing, an S&P Global Mobility analysis of inventory data shows a 91% increase in advertised new-vehicle dealer stock at the end of December 2022 compared to February, a sharp 43% uptick compared to August 2022, and a 21% jump compared to October.

"Though we're not back to historical norms, inventory pressures are starting to ease," said Matt Trommer, S&P Global Mobility associate director of innovation product management for in-market reporting.

"The only real difference was domestic and European brands seeing improved inventories earlier in 2022, and Asian brands ramping up to a greater extent in the second half of '22 after actually going down in the February-to-August period," Trommer said. "In a few cases, we're seeing inventories coming up quite a bit. Jeep, GMC and Mazda are now showing a broad availability of vehicles. Other brands such as Honda, Kia and Subaru, however, are showing more limited availability."

"We're in the formative stages of inventory rebuilding following six months of year-over-year increases that ended 35 months of year-over-declines in July 2022," said Joe Langley, associate director of research and analysis for S&P Global Mobility's North American Light Vehicle Forecasting & Analysis team. "Stellantis is the closest to having normalized inventory. They are going to have to ask themselves, 'What do we do next?'"

In December, Ford, Chevrolet, Ram, and Jeep had about 300,000 units of leftover 2022 models advertised as available for sale. Those four brands accounted for 71% of 2022 advertised inventory listed by mainstream brand dealers - and 66% of all dealer-advertised inventory when including luxury marques. Among luxury brands, Mercedes-Benz and Lincoln still showed the most remaining 2022 vehicles in dealer advertised inventory, according to the S&P Global Mobility analysis.

That said, not every brand will be in the same circumstances. After the initial semiconductor crunch, GM, Ford, and Stellantis better managed their supply chains and are closer to being back to traditional production levels; the Japanese brands are still struggling with supply-chain issues. While less impacted, Hyundai and Kia are also dealing with structural issues of not having enough factory capacity to meet growing demand.

"We're seeing the US3 being the closest to normalized inventory and they will have to start asking themselves hard questions relating to production planning, product mix and pricing along with incentives activity," Langley said. "The surprise of 2023 will be vehicle availability. It will still be well below industry norms, but inventory for the spring selling season will be up 50-70% from 2022 levels."

Another element that could factor into increased consumer power in the new-car arena: A softening in inflated used-car values.

When COVID shut down new-car manufacturing, demand (and prices) for used cars soared starting in early 2021. Data from CARFAX, part of S&P Global Mobility, shows that – pre-COVID – average weekly dealer listing prices for used cars had held steady, slightly above $19,000. The first quarter of 2021 saw a rapid price shock that resulted in peak pricing of $29,025 in Q1 2022. But last fall, used-car prices started retreating. By mid-December, CARFAX data showed a retreat to $27,239. And while prices are nowhere near pre-COVID levels, there is no evidence that inflated prices will hold.

One potential easing of a price crash: A momentary drop-off in off-lease cars coming back during the three-year anniversary of the COVID shutdown, when sales cratered for several months in 2020. A shortfall in the certified-pre-owned segment might resume demand pressure on the new-car side and temporarily hold prices steady.

External Forces

There are usually multiple causes of swings in market behavior, and it appears US light vehicle sales have a perfect storm of culminating events that will come to a head starting in spring 2023: In addition to rebounding vehicle inventories, a sharp rise in U.S. lending rates, inflation leading to lower disposable income among households, and nervy macroeconomic headwinds are worrying US consumers.

Already there are storm clouds on the horizon in terms of demand destruction. The daily new-car selling rate metric remained remarkably steady in the second half of 2022, even while some pockets of inventory accumulated. While stubbornly sticky low levels of inventory dampened year-end clearance incentives, any backward movement in the daily selling metric to begin 2023 could be signal of a retrenching auto consumer.

Households are eyeing the uncertain economy as a reason to hold back on new purchases. If workers do not receive 2023 pay raises commensurate with 2022's sudden inflationary spike, and large-scale layoffs continue, that will prompt conservatism in household capital expenditures.

"Ongoing supply chain challenges and recessionary fears will result in a cautious build-back for the market," said Chris Hopson, manager of North American light vehicle sales forecasting for S&P Global Mobility. "US consumers are hunkering down, and recovery towards pre-pandemic vehicle demand levels feels like a hard sell. Inventory and incentive activity will be key barometers to gauge potential demand destruction."

From a forecasting perspective, S&P Global Mobility recently downgraded the US demand settings for 2023 due to darkening economic clouds. The immediate release of pent-up demand of the past two years that many OEMs anticipated would absorb increasing production is now wavering, and may be eliminated altogether if consumers retrench their spending habits. This will prompt downward pressure on vehicle pricing.

Who Blinks First?

Where will the discounts first appear? Likely in full-size trucks. GM, Ford and Stellantis need full-size truck volumes and profits to support investment in their electrified futures. GM is the only one of the three that has incremental capacity to produce more full-size pickups – whether they're ICE or BEV. Ford is capacity-constrained until Blue Oval City comes online in the second half of 2025, and Stellantis has their own limitations in the short-term.

"This essentially puts GM in the driver's seat if they want to increase incentives to drive additional volume. If they do this, Ford and Stellantis will be forced to follow," Langley said. "There is still room for these manufacturers to increase incentives on their pickups and still be ahead on the revenue side if they experience comparable sales improvements from those higher incentives."

After all, pre-COVID incentives on big pickups were running $6,000 per unit in January 2020, and the Detroit automakers were still profitable. But recently, demand for pickups has waned as more buyers move to SUVs.

Despite full-size pickups' important contributions to each brand's business case and factory output, the share of half-ton retail sales has been declining for more than two years, according to S&P Global Mobility data. The segment's retail share in Q3 2022 was 7.8% – lower than in any other quarter dating back to Q3 2012.

Another area of potential incentive skirmish? Likely in a high-volume segment with plenty of players, such as mainstream compact SUVs. In addition, a competitive luxury market with additional pressure from Tesla could see a higher-end brand with resurgent inventories use the opportunity to grab share. Meanwhile, Tesla's recent price cuts across its lineup could prompt a price war in the BEV space.

At least one luxury automaker has stated it is openly looking at conquesting its rivals, and is already injecting money into the market to capture share. They see it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and are thinking that investing earlier in incentives – either cash on the hood, or subsidized lending rates – will result in the best chance to grab share. Meanwhile, another luxury brand with already strong days' supply is cranking up subsidized lease deals.

The next automaker's sales chief willing to cede market share without a fight will be the first one. Performance bonuses, career trajectories, and factory output requirements hinge on it. Furthermore, failing to spend to retain market share has downstream costs: The cost of losing loyal customers, multiplied by the cost of thousands of conquests needed to replace them, must also be considered. Also, automakers' and suppliers' factories need to run at high percentages of capacity to be profitable. Lofty talk of inventory control sounds great, until just-built vehicles start stacking up in factory-overflow lots.

Remember: Average transaction prices in December were $49,500, so for every 20,000 vehicles built, OEMs can generate nearly $1 billion in revenue – a tempting carrot for OEMs when revenue goals are under pressure.

As a result, spring and summer of 2023 could force automakers into aggressively pursuing customers with incentives while attempting to maintain the healthy profit margins they have seen for the past two years.

The upshot will be a chaotic accordion effect in monthly sales results, as fluctuating inventories run head-on into unsettled consumer confidence and numerous industry and macroeconomic conditions. Automakers and dealers will be hard pressed to find a consistently successful sales strategy that allows them to maintain or increase share during such uncertain times.

About S&P Global Mobility (www.spglobal.com/mobility)

At S&P Global Mobility, we provide invaluable insights derived from unmatched automotive data, enabling our customers to anticipate change and make decisions with conviction. Our expertise helps them to optimize their businesses, reach the right consumers, and shape the future of mobility. We open the door to automotive innovation, revealing the buying patterns of today and helping customers plan for the emerging technologies of tomorrow.

S&P Global Mobility is a division of S&P Global (NYSE: SPGI). S&P Global is the world's foremost provider of credit ratings, benchmarks, analytics and workflow solutions in the global capital, commodity and automotive markets. With every one of our offerings, we help many of the world's leading organizations navigate the economic landscape so they can plan for tomorrow, today. For more information, visit www.spglobal.com/mobility.

Editor's Note: This report is from S&P Global Mobility, and not S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Media Contact:

Michelle Culver

S&P Global Mobility

248.728.7496 or 248.342.6211

Michelle.culver@spglobal.com

View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/sp-global-mobility-special-report-us-automotive-market-share-wars-will-resume-in-2023-301737123.html

SOURCE S&P Global Mobility

Uncategorized

Key shipping company files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy

The Illinois-based general freight trucking company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy to reorganize.

The U.S. trucking industry has had a difficult beginning of the year for 2024 with several logistics companies filing for bankruptcy to seek either a Chapter 7 liquidation or Chapter 11 reorganization.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a lot of supply chain issues for logistics companies and also created a shortage of truck drivers as many left the business for other occupations. Shipping companies, in the meantime, have had extreme difficulty recruiting new drivers for thousands of unfilled jobs.

Related: Tesla rival’s filing reveals Chapter 11 bankruptcy is possible

Freight forwarder company Boateng Logistics joined a growing list of shipping companies that permanently shuttered their businesses as the firm on Feb. 22 filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy with plans to liquidate.

The Carlsbad, Calif., logistics company filed its petition in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of California listing assets up to $50,000 and and $1 million to $10 million in liabilities. Court papers said it owed millions of dollars in liabilities to trucking, logistics and factoring companies. The company filed bankruptcy before any creditors could take legal action.

Lawsuits force companies to liquidate in bankruptcy

Lawsuits, however, can force companies to file bankruptcy, which was the case for J.J. & Sons Logistics of Clint, Texas, which on Jan. 22 filed for Chapter 7 liquidation in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Texas. The company filed bankruptcy four days before the scheduled start of a trial for a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of a former company truck driver who had died from drowning in 2016.

California-based logistics company Wise Choice Trans Corp. shut down operations and filed for Chapter 7 liquidation on Jan. 4 in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of California, listing $1 million to $10 million in assets and liabilities.

The Hayward, Calif., third-party logistics company, founded in 2009, provided final mile, less-than-truckload and full truckload services, as well as warehouse and fulfillment services in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Chapter 7 filing also implemented an automatic stay against all legal proceedings, as the company listed its involvement in four legal actions that were ongoing or concluded. Court papers reportedly did not list amounts for damages.

In some cases, debtors don't have to take a drastic action, such as a liquidation, and can instead file a Chapter 11 reorganization.

Shutterstock

Nationwide Cargo seeks to reorganize its business

Nationwide Cargo Inc., a general freight trucking company that also hauls fresh produce and meat, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Illinois with plans to reorganize its business.

The East Dundee, Ill., shipping company listed $1 million to $10 million in assets and $10 million to $50 million in liabilities in its petition and said funds will not be available to pay unsecured creditors. The company operates with 183 trucks and 171 drivers, FreightWaves reported.

Nationwide Cargo's three largest secured creditors in the petition were Equify Financial LLC (owed about $3.5 million,) Commercial Credit Group (owed about $1.8 million) and Continental Bank NA (owed about $676,000.)

The shipping company reported gross revenue of about $34 million in 2022 and about $40 million in 2023. From Jan. 1 until its petition date, the company generated $9.3 million in gross revenue.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

bankruptcy pandemic covid-19 stocksUncategorized

Key shipping company files Chapter 11 bankruptcy

The Illinois-based general freight trucking company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy to reorganize.

The U.S. trucking industry has had a difficult beginning of the year for 2024 with several logistics companies filing for bankruptcy to seek either a Chapter 7 liquidation or Chapter 11 reorganization.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a lot of supply chain issues for logistics companies and also created a shortage of truck drivers as many left the business for other occupations. Shipping companies, in the meantime, have had extreme difficulty recruiting new drivers for thousands of unfilled jobs.

Related: Tesla rival’s filing reveals Chapter 11 bankruptcy is possible

Freight forwarder company Boateng Logistics joined a growing list of shipping companies that permanently shuttered their businesses as the firm on Feb. 22 filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy with plans to liquidate.

The Carlsbad, Calif., logistics company filed its petition in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of California listing assets up to $50,000 and and $1 million to $10 million in liabilities. Court papers said it owed millions of dollars in liabilities to trucking, logistics and factoring companies. The company filed bankruptcy before any creditors could take legal action.

Lawsuits force companies to liquidate in bankruptcy

Lawsuits, however, can force companies to file bankruptcy, which was the case for J.J. & Sons Logistics of Clint, Texas, which on Jan. 22 filed for Chapter 7 liquidation in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Texas. The company filed bankruptcy four days before the scheduled start of a trial for a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of a former company truck driver who had died from drowning in 2016.

California-based logistics company Wise Choice Trans Corp. shut down operations and filed for Chapter 7 liquidation on Jan. 4 in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of California, listing $1 million to $10 million in assets and liabilities.

The Hayward, Calif., third-party logistics company, founded in 2009, provided final mile, less-than-truckload and full truckload services, as well as warehouse and fulfillment services in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Chapter 7 filing also implemented an automatic stay against all legal proceedings, as the company listed its involvement in four legal actions that were ongoing or concluded. Court papers reportedly did not list amounts for damages.

In some cases, debtors don't have to take a drastic action, such as a liquidation, and can instead file a Chapter 11 reorganization.

Shutterstock

Nationwide Cargo seeks to reorganize its business

Nationwide Cargo Inc., a general freight trucking company that also hauls fresh produce and meat, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Illinois with plans to reorganize its business.

The East Dundee, Ill., shipping company listed $1 million to $10 million in assets and $10 million to $50 million in liabilities in its petition and said funds will not be available to pay unsecured creditors. The company operates with 183 trucks and 171 drivers, FreightWaves reported.

Nationwide Cargo's three largest secured creditors in the petition were Equify Financial LLC (owed about $3.5 million,) Commercial Credit Group (owed about $1.8 million) and Continental Bank NA (owed about $676,000.)

The shipping company reported gross revenue of about $34 million in 2022 and about $40 million in 2023. From Jan. 1 until its petition date, the company generated $9.3 million in gross revenue.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

bankruptcy pandemic covid-19 stocksUncategorized

Tight inventory and frustrated buyers challenge agents in Virginia

With inventory a little more than half of what it was pre-pandemic, agents are struggling to find homes for clients in Virginia.

No matter where you are in the state, real estate agents in Virginia are facing low inventory conditions that are creating frustrating scenarios for their buyers.

“I think people are getting used to the interest rates where they are now, but there is just a huge lack of inventory,” said Chelsea Newcomb, a RE/MAX Realty Specialists agent based in Charlottesville. “I have buyers that are looking, but to find a house that you love enough to pay a high price for — and to be at over a 6.5% interest rate — it’s just a little bit harder to find something.”

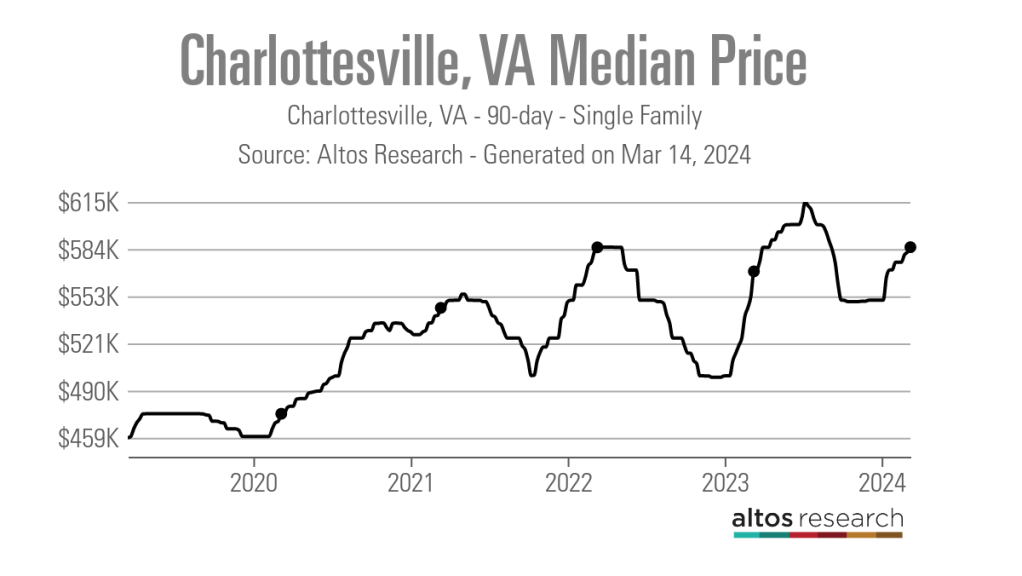

Newcomb said that interest rates and higher prices, which have risen by more than $100,000 since March 2020, according to data from Altos Research, have caused her clients to be pickier when selecting a home.

“When rates and prices were lower, people were more willing to compromise,” Newcomb said.

Out in Wise, Virginia, near the westernmost tip of the state, RE/MAX Cavaliers agent Brett Tiller and his clients are also struggling to find suitable properties.

“The thing that really stands out, especially compared to two years ago, is the lack of quality listings,” Tiller said. “The slightly more upscale single-family listings for move-up buyers with children looking for their forever home just aren’t coming on the market right now, and demand is still very high.”

Statewide, Virginia had a 90-day average of 8,068 active single-family listings as of March 8, 2024, down from 14,471 single-family listings in early March 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Altos Research. That represents a decrease of 44%.

In Newcomb’s base metro area of Charlottesville, there were an average of only 277 active single-family listings during the same recent 90-day period, compared to 892 at the onset of the pandemic. In Wise County, there were only 56 listings.

Due to the demand from move-up buyers in Tiller’s area, the average days on market for homes with a median price of roughly $190,000 was just 17 days as of early March 2024.

“For the right home, which is rare to find right now, we are still seeing multiple offers,” Tiller said. “The demand is the same right now as it was during the heart of the pandemic.”

According to Tiller, the tight inventory has caused homebuyers to spend up to six months searching for their new property, roughly double the time it took prior to the pandemic.

For Matt Salway in the Virginia Beach metro area, the tight inventory conditions are creating a rather hot market.

“Depending on where you are in the area, your listing could have 15 offers in two days,” the agent for Iron Valley Real Estate Hampton Roads | Virginia Beach said. “It has been crazy competition for most of Virginia Beach, and Norfolk is pretty hot too, especially for anything under $400,000.”

According to Altos Research, the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News housing market had a seven-day average Market Action Index score of 52.44 as of March 14, making it the seventh hottest housing market in the country. Altos considers any Market Action Index score above 30 to be indicative of a seller’s market.

Further up the coastline on the vacation destination of Chincoteague Island, Long & Foster agent Meghan O. Clarkson is also seeing a decent amount of competition despite higher prices and interest rates.

“People are taking their time to actually come see things now instead of buying site unseen, and occasionally we see some seller concessions, but the traffic and the demand is still there; you might just work a little longer with people because we don’t have anything for sale,” Clarkson said.

“I’m busy and constantly have appointments, but the underlying frenzy from the height of the pandemic has gone away, but I think it is because we have just gotten used to it.”

While much of the demand that Clarkson’s market faces is for vacation homes and from retirees looking for a scenic spot to retire, a large portion of the demand in Salway’s market comes from military personnel and civilians working under government contracts.

“We have over a dozen military bases here, plus a bunch of shipyards, so the closer you get to all of those bases, the easier it is to sell a home and the faster the sale happens,” Salway said.

Due to this, Salway said that existing-home inventory typically does not come on the market unless an employment contract ends or the owner is reassigned to a different base, which is currently contributing to the tight inventory situation in his market.

Things are a bit different for Tiller and Newcomb, who are seeing a decent number of buyers from other, more expensive parts of the state.

“One of the crazy things about Louisa and Goochland, which are kind of like suburbs on the western side of Richmond, is that they are growing like crazy,” Newcomb said. “A lot of people are coming in from Northern Virginia because they can work remotely now.”

With a Market Action Index score of 50, it is easy to see why people are leaving the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria market for the Charlottesville market, which has an index score of 41.

In addition, the 90-day average median list price in Charlottesville is $585,000 compared to $729,900 in the D.C. area, which Newcomb said is also luring many Virginia homebuyers to move further south.

“They are very accustomed to higher prices, so they are super impressed with the prices we offer here in the central Virginia area,” Newcomb said.

For local buyers, Newcomb said this means they are frequently being outbid or outpriced.

“A couple who is local to the area and has been here their whole life, they are just now starting to get their mind wrapped around the fact that you can’t get a house for $200,000 anymore,” Newcomb said.

As the year heads closer to spring, triggering the start of the prime homebuying season, agents in Virginia feel optimistic about the market.

“We are seeing seasonal trends like we did up through 2019,” Clarkson said. “The market kind of soft launched around President’s Day and it is still building, but I expect it to pick right back up and be in full swing by Easter like it always used to.”

But while they are confident in demand, questions still remain about whether there will be enough inventory to support even more homebuyers entering the market.

“I have a lot of buyers starting to come off the sidelines, but in my office, I also have a lot of people who are going to list their house in the next two to three weeks now that the weather is starting to break,” Newcomb said. “I think we are going to have a good spring and summer.”

real estate housing market pandemic covid-19 interest rates-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International7 days ago

International7 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International7 days ago

International7 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges