Uncategorized

Seven ways to fix the broken NHS ambulance services

So far, attempts to fix the emergency services crisis have largely involved short-term solutions without looking at the root causes.

As the NHS marks its 75th year, the urgent and emergency care services it provides have never been in a bigger crisis. Against the backdrop of 10.6 million 999 calls answered in 2022-22, which is 2.6 million more than in 2020-21, media reports have consistently highlighted severe ambulance delays. Patients’ safety is being compromised. Some people have died as a result.

Among ambulance staff, morale is at an all-time low. Sickness and absence rates are the highest – and show the highest rate of increase – of all NHS organisations.

Earlier attempts to remedy this situation have largely involved money being thrown at the service, as a short-term, “sticking plaster” approach, that fails to address the key issues. I have been studying ambulance services for more than 15 years. My research identifies seven problems the emergency services are facing – and how to fix them.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the launch of the NHS, we’ve commissioned a series of articles addressing the biggest challenges the service now faces. We want to understand not only what needs to change, but the knock-on effects on other parts of this extraordinarily complex health system.

1. Expand the workforce

Ambulance jobs have been shown to be highly demanding and come with significant performance pressures. There is also a notable lack of career and development opportunities. Paramedics speak of low job satisfaction and poor mental health, related to insufficient pay, stressful working conditions and intense workloads.

Given the record numbers leaving for less stressful and better paid jobs elsewhere, it is clear that the NHS needs a long-term solution.

In January 2023, the government announced its NHS Recovery Plan. This plan is predicated on having more staff, yet does not adequately address how to improve recruitment and retaining.

2. Support existing staff

The continuing and unhealthy focus on performance targets is resulting in negative outcomes for both patient care and workforce morale. The pandemic has only worsened already high rates of mental health issues, including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Providing mental health support and counselling services will improve staff wellbeing. This in turn will make it easier to maintain adequate staffing and safe levels of service delivery.

In addition, staff also need training to deal with rising numbers of mental health related calls. The recent announcement that the Metropolitan Police will stop responding to most mental health calls in London, by the end of August, will only put more pressure on the emergency services.

An integrated approach between ambulance services and other agencies is required to prevent harm to both staff and patients.

3. Improve ambulance services commissioning

Ambulance services were introduced relatively late to the NHS family in 1974 prior to which they were part of local government function. As a result, they have remained on the periphery of decision-making, while not being immune to the constant churning and change within the NHS.

Ambulance commissioning – the process by which local emergency healthcare needs are assessed and planned for – is a highly complex system. Multiple NHS organisations and local councils across England have to work together to create a model for delivering ambulance provision across the country through the nation’s ten ambulance trusts.

This often means that one ambulance trust might be delivering services across multiple areas, catering to different health needs with different delivery options. The lack of consistency in the commissioning framework has been criticised by the National Audit Office (the public spending watchdog) as well as by the government’s Public Accounts Committee.

The Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, the key representative body for the services, has warned that this risks duplictaion and fragmentation of services and called for more efficient decision-making, a call which healthcare scholars have echoed.

4. Provide continuity of care

In 2022-2023, one in four ambulances is experiencing delays of more than 30 minutes, which is twice as long as the standard for handover time from ambulance to hospital. These delays are having a disastrous impact.

Several causes have been identified, including insufficient hospital beds and slow patient flow meaning more people getting stuck in the system and not moving through efficiently.

Further, the 999/111 system has been found to be highly risk averse, meaning more ambulances are sent out than should be. Patients, meanwhile, struggle to access the care they need in the community, which also results in more heading to A&E or calling 999.

The NHS needs better protocols, better collaboration and better information sharing, between healthcare providers, to ensure a more seamless continuity of care. Crucially, this would reduce the number of patients going to hospital when they don’t actually need to.

5. Update the 999 call system

According to the most recent data, average response times for Category 1 (life threatening) calls, in England, is 8.17 minutes and for Category 2 (urgent but not life threatening), 32.24 minutes. Against the standards of seven minutes and 18 minutes, respectively, these averages represent significant delays.

Ambulance services are working to an outdated operating model which no longer reflects the reality on the ground: older population groups with complex health needs as well as the rising numbers of mental health issues.

Paramedics have also changed. They have acquired greater clinical skills. They also having better treatment options at their disposal, which the current 999 system fails to properly use.

The government’s own briefings make clear that it knows this. To better understand what patients actually need, the NHS needs greater clarity on published data and to exlore alternatives. Having nurses, for example, manage low-priority ambulance calls has been shown to reduce the need for ambulances.

6. Make better use of resources and tech

Unwarranted variations in ambulance service delivery, fleet procurement and treatment protocols is leading to increasing, but avoidable, inefficiency.

The NHS needs systems that ensure better allocation of ambulance resources and to minimise waste. Using data and analytics would help to identify areas with high demand, strategically position ambulances and implement more dynamic deployment strategies.

Further, ambulance staff lose vital knowledge about patients once they are handed over to hospitals because ambulance data is not routinely linked with other NHS organisations. Research shows that improving data sharing would help to improve care.

More broadly, upgrading the service’s technology and innovation capacity – from medical equipment on ambulances and electronic patient records to telemedicine capabilities is key. This will help improve communication, coordination and patient care.

7. Allocate adequate funding

Ambulance services have struggled with historical levels of under-funding. The latest demand and capacity review forecasts an annual funding gap of £237.5 million.

Pressures of meeting the increasing 999 demand have been again highlighted by parliament and experts, including in my own research.

While the additional funds promised in the NHS Recovery Plan will help the service in the short term, COVID-19 has made clear the need for constant appraisal to ensure that ambulance services are adequately resourced.

To fix the emergency services will require imagination, conviction and decisiveness on the part of our political leaders. History suggests a royal commission – like those appointed to advise on how to reform the House of Lords and the criminal justice system – could provide a way forward. Everyone, from the NHS and ambulance trusts to paramedics, policy makers, academics and the public, needs to work together to create a modern emergency service that is fit for purpose.

Paresh Wankhade is a Trustee at the Fire Service Research and Training Trust (FSRTT).

treatment pandemic covid-19 recoveryUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

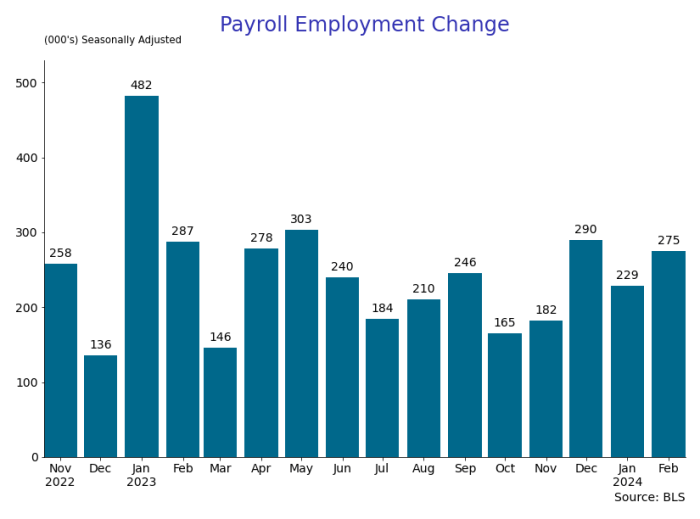

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

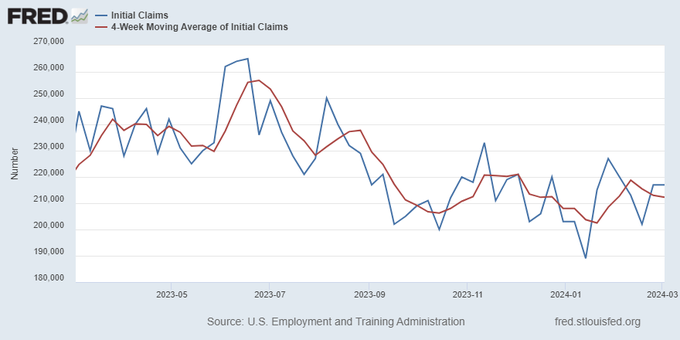

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

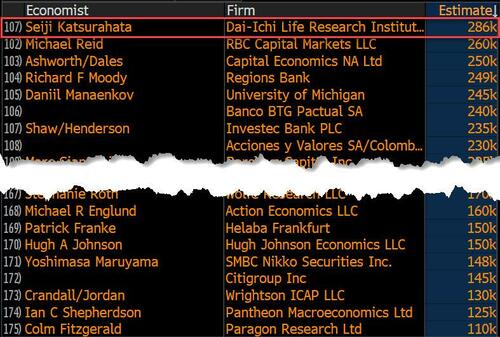

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex