Government

Racial wealth gaps are yet another thing the US and UK have in common

The legacy of racism in both the United States and the United Kingdom has impacted the ability of Blacks and other ethnic groups to accumulate wealth.

It’s an old saying that Britain and America are two countries separated by a common language.

But they are united by racial wealth gaps that formed at a similar time for related reasons. Black Britons of the “Windrush generation,” arriving in Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973, and Black Americas from the Great Migration of the 1940s-1970s encountered similar disadvantages that were reproduced in the last 50 years.

Today, examining household assets, Black Britons of Caribbean backgrounds have 20 pence on the £1 compared to white Britons. Black Britons of African background – more recently arrived in Britain – have just 10 pence on the £1 compared to white Britons.

In the U.S., Black Americans have assets about 15 to 20 cents on the $1 compared to whites.

This is in large part the result of policymakers in both countries putting up roadblocks to Black advancement at the time they instituted policies to grow the middle class.

In my view as a historian of slavery, capitalism and African American inequality, it’s not just the long shadow of enslavement, which Britain abolished in its western colonies in 1833 and the U.S. ended in 1865 with passage of the 13th Amendment.

When Black members of the British Commonwealth moved to Britain starting in 1948 and African Americans moved from the South to the North and West, they encountered new obstacles.

The long struggle for equal job opportunities has had a lasting effect on the ability to accrue wealth and pass it on to subsequent generations.

The British illusion of opportunity

The moment Black opportunity in Britain opened up was June 22, 1948, when the British ship Empire Windrush docked on the River Thames, disembarking 802 passengers of Caribbean background in England.

They led the first sustained Black migration, the Windrush generation, mostly Black and Asian, arriving in Britain between 1948 and 1973.

U.K. employers wanted their labor amid a post-World War II shortage.

About a third of Windrush passengers were veterans of the British forces who served in World War II and recruited by employers for skilled jobs.

Caribbean women, for instance, became vital to the new U.K. National Health Service as nurses, cooks and cleaners, many caring for patients by night and families by day.

But, as British journalist Afua Hirsch argues, they faced persistent discrimination in housing and jobs. Employers wanted them as laborers, not neighbors, and they faced hostility from those determined to “Keep England White.”

When a Bristol bus company refused to employ Black conductors and drivers, Black workers counter-organized, staging a successful Bristol bus boycott against employment discrimination.

Such action led to the 1964 Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, which helped catalyze the 1965 U.K. Race Relations Act banning public discrimination and made promoting hatred based on “colour, race, or ethnic or national origins” a crime.

Meanwhile, civil rights leaders such as Olive Morris fought for economic inclusion through organizations like the Black Workers Movement. These efforts helped include Black workers in unionized industry and led to wage gains.

The American allure of opportunity

While the Windrush generation took shape, African Americans too were moving north and west in search of opportunity. Journalist Isabel Wilkerson contends that “the Great Migration had more in common with the vast movements of refugees from famine, war, and genocide in other parts of the world.”

In the three decades following the Great Depression, the American wage structure became more equal than at any time before or since, a process economic historians term “The Great Compression.” Between 1940 and 1960, the distance between earners in the top 10% and bottom 90% narrowed by a third.

But policies giving white Americans a boost up the ladder tended to hamstring African Americans.

Social Security initially excluded most Black workers. Union wages rose, but African Americans were underrepresented in union jobs.

Home loan guarantees went to white families and specifically excluded Black-occupied properties in many U.S. cities.

Redlining was the practice of denying loan guarantees to properties occupied by Black and other minority residents. It became a self-fulfilling prophesy of disinvestment and declining values.

Meanwhile, post-WWII programs to improve social mobility, like the 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, or GI Bill, largely benefited white veterans by expanding the middle class with job, college and home loan assistance.

Historian Matthew F. Delmont argues that “by funneling resources to white veterans and denying loans to Black veterans, the GI Bill intensified the racial wealth gap and shared the terrain of opportunity in America for decades after the war.”

In the 1960s, legal barriers gave way to what African American Studies scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor calls “predatory inclusion” in home ownership, finance and education.

By the time Black Americans began to narrow a persistent wealth gap, the economy was paying diminishing returns to workers.

The wealth-to-earnings ratio rose in the U.S. and U.K. after 1973, and Black Americans who had recently climbed one or two rungs on the ladder started to move backward relative to whites.

Britain’s failed promise

By the 1970s, multicultural Britain had taken shape. As British sociologist Paul Gilroy argues, Black Britain, including people of African and South Asian descent, had become a complex of class and cultures as diverse as England’s imperial geography that once included colonies in Asia, Africa and the Americas.

But diversity didn’t mean inclusion. Just as Black working-class Britons were making gains in unionized industry, that rung of the ladder cracked.

Starting in the late 1970s, factories closed or moved offshore, and ways into the middle class narrowed as the U.K. and U.S. pursued a strategy of more privatization and less government spending on social services.

Union strength declined across sectors, and worker wages stagnated. Many Black Britons were trapped in segregated neighborhoods and didn’t reap gains from rising home values. Today, 2 in 3 white British families own homes compared to 2 in 5 Black British families of Caribbean background and 1 in 5 Black British families of African background.

By the 2000s, those who lacked capital or technological skills in Britain had a hard time climbing up the economic ladder. Income inequality soared between 1979 and the early 2000s, reaching levels not seen since before WWII.

America’s reinvention of inequality

Meanwhile in the United States, legal barriers fell while the economy changed in ways that disadvantaged Black workers in new ways. In 1979 the average Black worker earned 82 cents on the dollar compared to white counterparts. By 2000, the earnings gap widened to 77 cents on the dollar.

The Great Recession of 2008 destroyed half of Black wealth, and in 2015 an estimated 1.5 million Black American men were missing from the economy, having died early, been incarcerated or shut out of the employment market – 8.2% of working-age African American men compared with 1.6% of white men in the same age range.

Despite wealth gains since 2016, Black wealth was more vulnerable and harder to accumulate.

The earnings gap remains wide today.

Black women workers in the U.S. earn 79 cents on the dollar compared to white women, and Black men earn 87% of white men’s wages.

Discrimination across the Atlantic

In the U.K., just before the pandemic, Black Britons of African and Caribbean background earned 85% and 87% of the wages of white Britons, respectively.

According to a study by two leading U.K. inequality think tanks, British women of color endure “intersecting structural barriers and discrimination faced at every point of the career pipeline, from school to university to employment.”

U.K. wealth is largely white, resulting from the “history of economic relations between Britain and the rest of the world, especially Africa, the Caribbean and Asia,” according to the Runnymede Trust, an inequality think tank.

Over the last 80 years, the underbelly of Britain and America is that both countries reinvented racial economic disadvantages.

Instead of making their economies fundamentally fair, racial exclusions gave way to inclusion that came with surcharges on opportunity while failing to rectify past wrongs.

Calvin Schermerhorn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

recession depression pandemic pence recession africa ukGovernment

Survey Shows Declining Concerns Among Americans About COVID-19

Survey Shows Declining Concerns Among Americans About COVID-19

A new survey reveals that only 20% of Americans view covid-19 as "a major threat"…

A new survey reveals that only 20% of Americans view covid-19 as "a major threat" to the health of the US population - a sharp decline from a high of 67% in July 2020.

What's more, the Pew Research Center survey conducted from Feb. 7 to Feb. 11 showed that just 10% of Americans are concerned that they will catch the disease and require hospitalization.

"This data represents a low ebb of public concern about the virus that reached its height in the summer and fall of 2020, when as many as two-thirds of Americans viewed COVID-19 as a major threat to public health," reads the report, which was published March 7.

According to the survey, half of the participants understand the significance of researchers and healthcare providers in understanding and treating long COVID - however 27% of participants consider this issue less important, while 22% of Americans are unaware of long COVID.

What's more, while Democrats were far more worried than Republicans in the past, that gap has narrowed significantly.

"In the pandemic’s first year, Democrats were routinely about 40 points more likely than Republicans to view the coronavirus as a major threat to the health of the U.S. population. This gap has waned as overall levels of concern have fallen," reads the report.

More via the Epoch Times;

The survey found that three in ten Democrats under 50 have received an updated COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 66 percent of Democrats ages 65 and older.

Moreover, 66 percent of Democrats ages 65 and older have received the updated COVID-19 vaccine, while only 24 percent of Republicans ages 65 and older have done so.

“This 42-point partisan gap is much wider now than at other points since the start of the outbreak. For instance, in August 2021, 93 percent of older Democrats and 78 percent of older Republicans said they had received all the shots needed to be fully vaccinated (a 15-point gap),” it noted.

COVID-19 No Longer an Emergency

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently issued its updated recommendations for the virus, which no longer require people to stay home for five days after testing positive for COVID-19.

The updated guidance recommends that people who contracted a respiratory virus stay home, and they can resume normal activities when their symptoms improve overall and their fever subsides for 24 hours without medication.

“We still must use the commonsense solutions we know work to protect ourselves and others from serious illness from respiratory viruses, this includes vaccination, treatment, and staying home when we get sick,” CDC director Dr. Mandy Cohen said in a statement.

The CDC said that while the virus remains a threat, it is now less likely to cause severe illness because of widespread immunity and improved tools to prevent and treat the disease.

“Importantly, states and countries that have already adjusted recommended isolation times have not seen increased hospitalizations or deaths related to COVID-19,” it stated.

The federal government suspended its free at-home COVID-19 test program on March 8, according to a website set up by the government, following a decrease in COVID-19-related hospitalizations.

According to the CDC, hospitalization rates for COVID-19 and influenza diseases remain “elevated” but are decreasing in some parts of the United States.

International

Rand Paul Teases Senate GOP Leader Run – Musk Says “I Would Support”

Rand Paul Teases Senate GOP Leader Run – Musk Says "I Would Support"

Republican Kentucky Senator Rand Paul on Friday hinted that he may jump…

Republican Kentucky Senator Rand Paul on Friday hinted that he may jump into the race to become the next Senate GOP leader, and Elon Musk was quick to support the idea. Republicans must find a successor for periodically malfunctioning Mitch McConnell, who recently announced he'll step down in November, though intending to keep his Senate seat until his term ends in January 2027, when he'd be within weeks of turning 86.

So far, the announced field consists of two quintessential establishment types: John Cornyn of Texas and John Thune of South Dakota. While John Barrasso's name had been thrown around as one of "The Three Johns" considered top contenders, the Wyoming senator on Tuesday said he'll instead seek the number two slot as party whip.

Paul used X to tease his potential bid for the position which -- if the GOP takes back the upper chamber in November -- could graduate from Minority Leader to Majority Leader. He started by telling his 5.1 million followers he'd had lots of people asking him about his interest in running...

Thousands of people have been asking if I'd run for Senate leadership...

— Rand Paul (@RandPaul) March 8, 2024

...then followed up with a poll in which he predictably annihilated Cornyn and Thune, taking a 96% share as of Friday night, with the other two below 2% each.

????????️VOTE NOW ????️ ???? Who would you like to be the next Senate leader?

— Rand Paul (@RandPaul) March 8, 2024

Elon Musk was quick to back the idea of Paul as GOP leader, while daring Cornyn and Thune to follow Paul's lead by throwing their names out for consideration by the Twitter-verse X-verse.

I would support Rand Paul and suspect that other candidates will not actually run polls out of concern for the results, but let’s see if they will!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 8, 2024

Paul has been a stalwart opponent of security-state mass surveillance, foreign interventionism -- to include shoveling billions of dollars into the proxy war in Ukraine -- and out-of-control spending in general. He demonstrated the latter passion on the Senate floor this week as he ridiculed the latest kick-the-can spending package:

This bill is an insult to the American people. The earmarks are all the wasteful spending that you could ever hope to see, and it should be defeated. Read more: https://t.co/Jt8K5iucA4 pic.twitter.com/I5okd4QgDg

— Senator Rand Paul (@SenRandPaul) March 8, 2024

In February, Paul used Senate rules to force his colleagues into a grueling Super Bowl weekend of votes, as he worked to derail a $95 billion foreign aid bill. "I think we should stay here as long as it takes,” said Paul. “If it takes a week or a month, I’ll force them to stay here to discuss why they think the border of Ukraine is more important than the US border.”

Don't expect a Majority Leader Paul to ditch the filibuster -- he's been a hardy user of the legislative delay tactic. In 2013, he spoke for 13 hours to fight the nomination of John Brennan as CIA director. In 2015, he orated for 10-and-a-half-hours to oppose extension of the Patriot Act.

Among the general public, Paul is probably best known as Capitol Hill's chief tormentor of Dr. Anthony Fauci, who was director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease during the Covid-19 pandemic. Paul says the evidence indicates the virus emerged from China's Wuhan Institute of Virology. He's accused Fauci and other members of the US government public health apparatus of evading questions about their funding of the Chinese lab's "gain of function" research, which takes natural viruses and morphs them into something more dangerous. Paul has pointedly said that Fauci committed perjury in congressional hearings and that he belongs in jail "without question."

Musk is neither the only nor the first noteworthy figure to back Paul for party leader. Just hours after McConnell announced his upcoming step-down from leadership, independent 2024 presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Jr voiced his support:

Mitch McConnell, who has served in the Senate for almost 40 years, announced he'll step down this November.

— Robert F. Kennedy Jr (@RobertKennedyJr) February 28, 2024

Part of public service is about knowing when to usher in a new generation. It’s time to promote leaders in Washington, DC who won’t kowtow to the military contractors or…

In a testament to the extent to which the establishment recoils at the libertarian-minded Paul, mainstream media outlets -- which have been quick to report on other developments in the majority leader race -- pretended not to notice that Paul had signaled his interest in the job. More than 24 hours after Paul's test-the-waters tweet-fest began, not a single major outlet had brought it to the attention of their audience.

That may be his strongest endorsement yet.

Government

The Great Replacement Loophole: Illegal Immigrants Score 5-Year Work Benefit While “Waiting” For Deporation, Asylum

The Great Replacement Loophole: Illegal Immigrants Score 5-Year Work Benefit While "Waiting" For Deporation, Asylum

Over the past several…

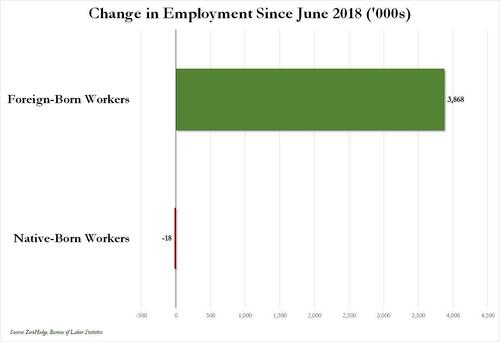

Over the past several months we've pointed out that there has been zero job creation for native-born workers since the summer of 2018...

... and that since Joe Biden was sworn into office, most of the post-pandemic job gains the administration continuously brags about have gone foreign-born (read immigrants, mostly illegal ones) workers.

And while the left might find this data almost as verboten as FBI crime statistics - as it directly supports the so-called "great replacement theory" we're not supposed to discuss - it also coincides with record numbers of illegal crossings into the United States under Biden.

In short, the Biden administration opened the floodgates, 10 million illegal immigrants poured into the country, and most of the post-pandemic "jobs recovery" went to foreign-born workers, of which illegal immigrants represent the largest chunk.

'But Tyler, illegal immigrants can't possibly work in the United States whilst awaiting their asylum hearings,' one might hear from the peanut gallery. On the contrary: ever since Biden reversed a key aspect of Trump's labor policies, all illegal immigrants - even those awaiting deportation proceedings - have been given carte blanche to work while awaiting said proceedings for up to five years...

... something which even Elon Musk was shocked to learn.

Wow, learn something new every day https://t.co/8MDtEEZGam

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 10, 2024

Which leads us to another question: recall that the primary concern for the Biden admin for much of 2022 and 2023 was soaring prices, i.e., relentless inflation in general, and rising wages in particular, which in turn prompted even Goldman to admit two years ago that the diabolical wage-price spiral had been unleashed in the US (diabolical, because nothing absent a major economic shock, read recession or depression, can short-circuit it once it is in place).

Well, there is one other thing that can break the wage-price spiral loop: a flood of ultra-cheap illegal immigrant workers. But don't take our word for it: here is Fed Chair Jerome Powell himself during his February 60 Minutes interview:

PELLEY: Why was immigration important?

POWELL: Because, you know, immigrants come in, and they tend to work at a rate that is at or above that for non-immigrants. Immigrants who come to the country tend to be in the workforce at a slightly higher level than native Americans do. But that's largely because of the age difference. They tend to skew younger.

PELLEY: Why is immigration so important to the economy?

POWELL: Well, first of all, immigration policy is not the Fed's job. The immigration policy of the United States is really important and really much under discussion right now, and that's none of our business. We don't set immigration policy. We don't comment on it.

I will say, over time, though, the U.S. economy has benefited from immigration. And, frankly, just in the last, year a big part of the story of the labor market coming back into better balance is immigration returning to levels that were more typical of the pre-pandemic era.

PELLEY: The country needed the workers.

POWELL: It did. And so, that's what's been happening.

Translation: Immigrants work hard, and Americans are lazy. But much more importantly, since illegal immigrants will work for any pay, and since Biden's Department of Homeland Security, via its Citizenship and Immigration Services Agency, has made it so illegal immigrants can work in the US perfectly legally for up to 5 years (if not more), one can argue that the flood of illegals through the southern border has been the primary reason why inflation - or rather mostly wage inflation, that all too critical component of the wage-price spiral - has moderated in in the past year, when the US labor market suddenly found itself flooded with millions of perfectly eligible workers, who just also happen to be illegal immigrants and thus have zero wage bargaining options.

None of this is to suggest that the relentless flood of immigrants into the US is not also driven by voting and census concerns - something Elon Musk has been pounding the table on in recent weeks, and has gone so far to call it "the biggest corruption of American democracy in the 21st century", but in retrospect, one can also argue that the only modest success the Biden admin has had in the past year - namely bringing inflation down from a torrid 9% annual rate to "only" 3% - has also been due to the millions of illegals he's imported into the country.

We would be remiss if we didn't also note that this so often carries catastrophic short-term consequences for the social fabric of the country (the Laken Riley fiasco being only the latest example), not to mention the far more dire long-term consequences for the future of the US - chief among them the trillions of dollars in debt the US will need to incur to pay for all those new illegal immigrants Democrat voters and low-paid workers. This is on top of the labor revolution that will kick in once AI leads to mass layoffs among high-paying, white-collar jobs, after which all those newly laid off native-born workers hoping to trade down to lower paying (if available) jobs will discover that hardened criminals from Honduras or Guatemala have already taken them, all thanks to Joe Biden.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex