Government

It’s the First Not Last Place To Start

The term “geopolitics” has a specific meaning, though in the context of assessing markets and their equally ubiquitous though purposefully non-specific “jitters”, it’s basically a catch-all, too. Should the stock market, in particular, take…

The term “geopolitics” has a specific meaning, though in the context of assessing markets and their equally ubiquitous though purposefully non-specific “jitters”, it’s basically a catch-all, too. Should the stock market, in particular, take a bad step, reflexive commentary is quick to call up geopolitics.

Such was absolutely the case late in January 2018 into the following month of February. Stocks were down. Kim Jung Un was firing missiles. Crazy-man Trump in all the Western media. These things were purportedly raising the global temperature to the point that it was in danger of becoming a flashpoint. Therefore, it sounded plausible (I guess) even stocks would pause their (latest) epic rise if to reassess these dangers.

There was even some absurd fuss about the imminent launch of World War III.

And if not geopolitics, of course, there’s always the Fed. If you didn’t think there was much to Korean weapons tests, and there wasn’t, then it must have been Janet Yellen’s hawkish successor Jay Powell to worry about once February 2018 began. After all, across all the news was this idea that good news was bad news; the better the US economy was doing, the more hawkish Powell would evolve in his first months and year in office.

One of my favorites:

“Economic news from the US has been stronger than anticipated,” said David Kuo, chief executive of financial services advisory Motley Fool. “So, perversely, the market correction has been caused by positive economic news”.

Markets worldwide suffer most when the most fundamental parts of them are doing their utmost best? Only if you think the Federal Reserve is the source of all life and energy.

The problem with these views is that they begin from an unchallenged assumption (taken from the other one that the Federal Reserve is the source of all life and energy).

We are taught from the start to believe that the economy is either in recession or booming. And if not the former, it can only be the latter. So, should markets tinge with uncertainty outside of any declared trough to the business cycle, our list of approved causation is inappropriately too limited (this assumption had actually been the mainstream view throughout the first half of 2008).

Must be “geopolitics”, then. Which one? Doesn’t matter. Pick one. There’s always something bad and the possibility for worse going on in the world.

Start with the unearned certainty on growth and inflation pressures, account for only temporary factors as necessary, leaving hunky dory sunshine never more than a news cycle away. The underlying suggestion is that the baseline is robust if not too much; thus, resolve today’s issue-of-the-day and we go right back to sunshine as if nothing happened.

See? Nothing to really worry about.

As it would turn out, neither the Fed’s rate hikes nor North Korea’s tempestuousness had anything to do with 2018 going the wrong way even though what did go wrong did end up with 2019 as a total economic, not geopolitical, mess. The underlying guess of a booming economy, globally synchronized growth, that is what was actually being questioned (flat curves especially) right from January 2018.

With very good reason, though more Japan than Korea.

This is not to downplay the high stakes and seriousness of various problems across the globe, including right now January 2022 in Ukraine and Communist arms surrounding Taiwan.

How about a growth scare that more and more seems, perhaps, not a scare? It’s the one possibility we’re never meant to ponder even for a moment.

Tracking PMI data on that account, the last half of last year had left a very clear downside trend that with the initial sentiment data for 2022 indicates at best its continuation or maybe an acceleration further downward to it.

Last week, I highlighted the Federal Reserve’s New York branch and its Empire Manufacturing survey which, frankly, collapsed in January. Dropping by more than thirty points in its headline index along with the same level for new orders, though just one month for one survey I thought it worth mentioning anyway.

The conventional explanation has been – while markets supposedly get more jittery from geopolitics – the pandemic, specifically omicron. It’s a plausible explanation, after all, New York being at the epicenter of the new variant’s seasonal uptick.

Very close to New York, however, the Fed’s Philadelphia branch rebounded in January from its own plunge during December. In this other one, the overall manufacturing estimate tumbled almost 25 pts last month, with the index for new orders giving up nearly 35. This month, the topline number recovered but only eight pts while new orders increased by barely more than four.

We’ve had our eyes on new orders specifically for matters unrelated to massed armies or even government pandemic overreactions. The vast and vastly obscured inventory cycle, however, and the potential for, again, a material slowdown keeps showing up in the data – and not just that for sentiment, nor for just the US.

Earlier today, IHS Markit marked down its own manufacturing numbers for the whole US economy. At a flash January reading of 55.0, that’s down from 57.8 in December, noticeably distant from July’s 63.8, and very clearly having gone decidedly in the wrong direction ever since.

On the services side of its ledger, Markit released some shocking data in the form of a major decline for the non-manufacturing PMI. This one crashed from 57.0 in December down to just barely 50 (50.8) the flash for January. That’s nearly four points less than the previous cycle low, September 2021, which, of course, had been immediately blamed entirely on delta.

Governments in the US were clearly provoked substantially more, and in substantially more places, by delta than have been due to omicron. So, while we might consider the latter as having had some negative impact maybe concentrated in a short timeframe like December or January figures, it sure doesn’t explain the overall trend and where things seem to be headed regardless of these transitory interruptions.

Lower highs, lower lows.

Furthermore, new orders. What IHS Markit had to say about them (both services and manufacturing) in its January data was one part spin, a bigger part uh oh:

New orders for goods and services continued to rise strongly, albeit registering the weakest rise since December 2020. The upturn in new orders was supported by the service sector, as manufacturers stated that new sales growth was often held back by weaker demand from clients amid price rises and efforts to work through inventories. [emphasis added]

A strong rise in orders that’s also the worst in thirteen months, technically true, sure, meaningless nonetheless though standard stuff which begins with the binary assumption I stated from the outset (if it isn’t recession, must be great). More important was that last bit: “efforts to work through inventories.”

That this is something new in the commentary is itself a substantial shift.

In other words, we know in bonds almost for certain what’s been keeping a lid on growth and inflation expectations for long-term yields going back almost a year now, even as the Fed’s rate hikes are incorporated into them, and it hasn’t been geopolitics nor particular strains of pandemic interruptions.

There’s been two of those over the preceding year and the growth scare just won’t go away; it sticks around in a way that neither “geopolitics” or coronavirus strains has nor is really meant to.

We’re never supposed to question the boom when that’s usually the first place to start.

Government

Survey Shows Declining Concerns Among Americans About COVID-19

Survey Shows Declining Concerns Among Americans About COVID-19

A new survey reveals that only 20% of Americans view covid-19 as "a major threat"…

A new survey reveals that only 20% of Americans view covid-19 as "a major threat" to the health of the US population - a sharp decline from a high of 67% in July 2020.

What's more, the Pew Research Center survey conducted from Feb. 7 to Feb. 11 showed that just 10% of Americans are concerned that they will catch the disease and require hospitalization.

"This data represents a low ebb of public concern about the virus that reached its height in the summer and fall of 2020, when as many as two-thirds of Americans viewed COVID-19 as a major threat to public health," reads the report, which was published March 7.

According to the survey, half of the participants understand the significance of researchers and healthcare providers in understanding and treating long COVID - however 27% of participants consider this issue less important, while 22% of Americans are unaware of long COVID.

What's more, while Democrats were far more worried than Republicans in the past, that gap has narrowed significantly.

"In the pandemic’s first year, Democrats were routinely about 40 points more likely than Republicans to view the coronavirus as a major threat to the health of the U.S. population. This gap has waned as overall levels of concern have fallen," reads the report.

More via the Epoch Times;

The survey found that three in ten Democrats under 50 have received an updated COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 66 percent of Democrats ages 65 and older.

Moreover, 66 percent of Democrats ages 65 and older have received the updated COVID-19 vaccine, while only 24 percent of Republicans ages 65 and older have done so.

“This 42-point partisan gap is much wider now than at other points since the start of the outbreak. For instance, in August 2021, 93 percent of older Democrats and 78 percent of older Republicans said they had received all the shots needed to be fully vaccinated (a 15-point gap),” it noted.

COVID-19 No Longer an Emergency

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently issued its updated recommendations for the virus, which no longer require people to stay home for five days after testing positive for COVID-19.

The updated guidance recommends that people who contracted a respiratory virus stay home, and they can resume normal activities when their symptoms improve overall and their fever subsides for 24 hours without medication.

“We still must use the commonsense solutions we know work to protect ourselves and others from serious illness from respiratory viruses, this includes vaccination, treatment, and staying home when we get sick,” CDC director Dr. Mandy Cohen said in a statement.

The CDC said that while the virus remains a threat, it is now less likely to cause severe illness because of widespread immunity and improved tools to prevent and treat the disease.

“Importantly, states and countries that have already adjusted recommended isolation times have not seen increased hospitalizations or deaths related to COVID-19,” it stated.

The federal government suspended its free at-home COVID-19 test program on March 8, according to a website set up by the government, following a decrease in COVID-19-related hospitalizations.

According to the CDC, hospitalization rates for COVID-19 and influenza diseases remain “elevated” but are decreasing in some parts of the United States.

Government

Rand Paul Teases Senate GOP Leader Run – Musk Says “I Would Support”

Rand Paul Teases Senate GOP Leader Run – Musk Says "I Would Support"

Republican Kentucky Senator Rand Paul on Friday hinted that he may jump…

Republican Kentucky Senator Rand Paul on Friday hinted that he may jump into the race to become the next Senate GOP leader, and Elon Musk was quick to support the idea. Republicans must find a successor for periodically malfunctioning Mitch McConnell, who recently announced he'll step down in November, though intending to keep his Senate seat until his term ends in January 2027, when he'd be within weeks of turning 86.

So far, the announced field consists of two quintessential establishment types: John Cornyn of Texas and John Thune of South Dakota. While John Barrasso's name had been thrown around as one of "The Three Johns" considered top contenders, the Wyoming senator on Tuesday said he'll instead seek the number two slot as party whip.

Paul used X to tease his potential bid for the position which -- if the GOP takes back the upper chamber in November -- could graduate from Minority Leader to Majority Leader. He started by telling his 5.1 million followers he'd had lots of people asking him about his interest in running...

Thousands of people have been asking if I'd run for Senate leadership...

— Rand Paul (@RandPaul) March 8, 2024

...then followed up with a poll in which he predictably annihilated Cornyn and Thune, taking a 96% share as of Friday night, with the other two below 2% each.

????????️VOTE NOW ????️ ???? Who would you like to be the next Senate leader?

— Rand Paul (@RandPaul) March 8, 2024

Elon Musk was quick to back the idea of Paul as GOP leader, while daring Cornyn and Thune to follow Paul's lead by throwing their names out for consideration by the Twitter-verse X-verse.

I would support Rand Paul and suspect that other candidates will not actually run polls out of concern for the results, but let’s see if they will!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 8, 2024

Paul has been a stalwart opponent of security-state mass surveillance, foreign interventionism -- to include shoveling billions of dollars into the proxy war in Ukraine -- and out-of-control spending in general. He demonstrated the latter passion on the Senate floor this week as he ridiculed the latest kick-the-can spending package:

This bill is an insult to the American people. The earmarks are all the wasteful spending that you could ever hope to see, and it should be defeated. Read more: https://t.co/Jt8K5iucA4 pic.twitter.com/I5okd4QgDg

— Senator Rand Paul (@SenRandPaul) March 8, 2024

In February, Paul used Senate rules to force his colleagues into a grueling Super Bowl weekend of votes, as he worked to derail a $95 billion foreign aid bill. "I think we should stay here as long as it takes,” said Paul. “If it takes a week or a month, I’ll force them to stay here to discuss why they think the border of Ukraine is more important than the US border.”

Don't expect a Majority Leader Paul to ditch the filibuster -- he's been a hardy user of the legislative delay tactic. In 2013, he spoke for 13 hours to fight the nomination of John Brennan as CIA director. In 2015, he orated for 10-and-a-half-hours to oppose extension of the Patriot Act.

Among the general public, Paul is probably best known as Capitol Hill's chief tormentor of Dr. Anthony Fauci, who was director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease during the Covid-19 pandemic. Paul says the evidence indicates the virus emerged from China's Wuhan Institute of Virology. He's accused Fauci and other members of the US government public health apparatus of evading questions about their funding of the Chinese lab's "gain of function" research, which takes natural viruses and morphs them into something more dangerous. Paul has pointedly said that Fauci committed perjury in congressional hearings and that he belongs in jail "without question."

Musk is neither the only nor the first noteworthy figure to back Paul for party leader. Just hours after McConnell announced his upcoming step-down from leadership, independent 2024 presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Jr voiced his support:

Mitch McConnell, who has served in the Senate for almost 40 years, announced he'll step down this November.

— Robert F. Kennedy Jr (@RobertKennedyJr) February 28, 2024

Part of public service is about knowing when to usher in a new generation. It’s time to promote leaders in Washington, DC who won’t kowtow to the military contractors or…

In a testament to the extent to which the establishment recoils at the libertarian-minded Paul, mainstream media outlets -- which have been quick to report on other developments in the majority leader race -- pretended not to notice that Paul had signaled his interest in the job. More than 24 hours after Paul's test-the-waters tweet-fest began, not a single major outlet had brought it to the attention of their audience.

That may be his strongest endorsement yet.

Government

The Great Replacement Loophole: Illegal Immigrants Score 5-Year Work Benefit While “Waiting” For Deporation, Asylum

The Great Replacement Loophole: Illegal Immigrants Score 5-Year Work Benefit While "Waiting" For Deporation, Asylum

Over the past several…

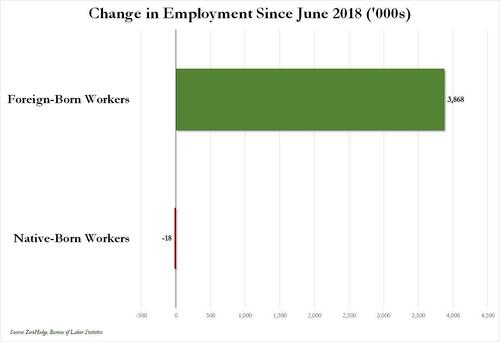

Over the past several months we've pointed out that there has been zero job creation for native-born workers since the summer of 2018...

... and that since Joe Biden was sworn into office, most of the post-pandemic job gains the administration continuously brags about have gone foreign-born (read immigrants, mostly illegal ones) workers.

And while the left might find this data almost as verboten as FBI crime statistics - as it directly supports the so-called "great replacement theory" we're not supposed to discuss - it also coincides with record numbers of illegal crossings into the United States under Biden.

In short, the Biden administration opened the floodgates, 10 million illegal immigrants poured into the country, and most of the post-pandemic "jobs recovery" went to foreign-born workers, of which illegal immigrants represent the largest chunk.

'But Tyler, illegal immigrants can't possibly work in the United States whilst awaiting their asylum hearings,' one might hear from the peanut gallery. On the contrary: ever since Biden reversed a key aspect of Trump's labor policies, all illegal immigrants - even those awaiting deportation proceedings - have been given carte blanche to work while awaiting said proceedings for up to five years...

... something which even Elon Musk was shocked to learn.

Wow, learn something new every day https://t.co/8MDtEEZGam

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 10, 2024

Which leads us to another question: recall that the primary concern for the Biden admin for much of 2022 and 2023 was soaring prices, i.e., relentless inflation in general, and rising wages in particular, which in turn prompted even Goldman to admit two years ago that the diabolical wage-price spiral had been unleashed in the US (diabolical, because nothing absent a major economic shock, read recession or depression, can short-circuit it once it is in place).

Well, there is one other thing that can break the wage-price spiral loop: a flood of ultra-cheap illegal immigrant workers. But don't take our word for it: here is Fed Chair Jerome Powell himself during his February 60 Minutes interview:

PELLEY: Why was immigration important?

POWELL: Because, you know, immigrants come in, and they tend to work at a rate that is at or above that for non-immigrants. Immigrants who come to the country tend to be in the workforce at a slightly higher level than native Americans do. But that's largely because of the age difference. They tend to skew younger.

PELLEY: Why is immigration so important to the economy?

POWELL: Well, first of all, immigration policy is not the Fed's job. The immigration policy of the United States is really important and really much under discussion right now, and that's none of our business. We don't set immigration policy. We don't comment on it.

I will say, over time, though, the U.S. economy has benefited from immigration. And, frankly, just in the last, year a big part of the story of the labor market coming back into better balance is immigration returning to levels that were more typical of the pre-pandemic era.

PELLEY: The country needed the workers.

POWELL: It did. And so, that's what's been happening.

Translation: Immigrants work hard, and Americans are lazy. But much more importantly, since illegal immigrants will work for any pay, and since Biden's Department of Homeland Security, via its Citizenship and Immigration Services Agency, has made it so illegal immigrants can work in the US perfectly legally for up to 5 years (if not more), one can argue that the flood of illegals through the southern border has been the primary reason why inflation - or rather mostly wage inflation, that all too critical component of the wage-price spiral - has moderated in in the past year, when the US labor market suddenly found itself flooded with millions of perfectly eligible workers, who just also happen to be illegal immigrants and thus have zero wage bargaining options.

None of this is to suggest that the relentless flood of immigrants into the US is not also driven by voting and census concerns - something Elon Musk has been pounding the table on in recent weeks, and has gone so far to call it "the biggest corruption of American democracy in the 21st century", but in retrospect, one can also argue that the only modest success the Biden admin has had in the past year - namely bringing inflation down from a torrid 9% annual rate to "only" 3% - has also been due to the millions of illegals he's imported into the country.

We would be remiss if we didn't also note that this so often carries catastrophic short-term consequences for the social fabric of the country (the Laken Riley fiasco being only the latest example), not to mention the far more dire long-term consequences for the future of the US - chief among them the trillions of dollars in debt the US will need to incur to pay for all those new illegal immigrants Democrat voters and low-paid workers. This is on top of the labor revolution that will kick in once AI leads to mass layoffs among high-paying, white-collar jobs, after which all those newly laid off native-born workers hoping to trade down to lower paying (if available) jobs will discover that hardened criminals from Honduras or Guatemala have already taken them, all thanks to Joe Biden.

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex