International

How To Adjust to Changing Market Conditions

In the last ten or so years, the US stock market has been unrepentant in always ripping higher when we think the bear market is just around the corner….

In the last ten or so years, the US stock market has been unrepentant in always ripping higher when we think the bear market is just around the corner.

Even a massive pandemic in which policymakers responded to with global lockdowns couldn’t keep stocks down for more than a month or so.

One of the primary factors that distinguish this bull market from those previous are the “Fed put,” the idea that the Federal Reserve will swiftly step in and save the day anytime the stock market significantly declines. This concept is not a fantasy in traders’ minds, as the actions of the Federal Reserve support this line of thinking.

Another is persistently low interest rates throughout the entire bull market cycle, which pushes investors into a “nowhere to hide” situation, where they’re forced to go further out on the risk curve and buy equities and other risk assets.

If the bank is paying 5% interest, it’s a lot easier to just do that rather than take significant risk for the allure of 8% annual returns from stocks.

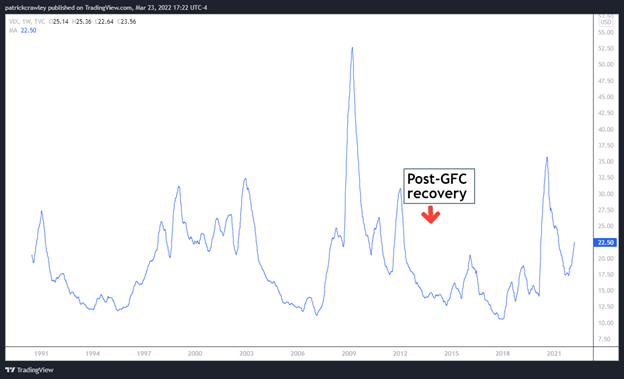

25-week moving average of VIX

As a result, any trader that cut their teeth trading stocks in this era doesn’t know what a true bear market is like. Maybe they’ve experienced momentary panic like during the flash crash or March 2020, but never prolonged bearish price action that makes traders lose all hope and look for new work.

And even those traders that went through the aftermath of Black Friday, the dotcom burst, and the Great Financial Crisis may have forgotten what it’s like because they’ve been printing money being long stocks for so many years.

For this reason, it’s crucial to learn how to respond and prepare for these conditions before they occur, or else you’re not only going to be unprepared to make trading decisions in what is a novel set of market conditions for you, but you’re going to be spending time during that market regime studying how to trade it, rather than having a leg up prior to the event.

That’s not to say reading some articles and books is sufficient preparation for a bear market, of course not. The only true teacher in such conditions is experience, lots of experience. However, if we compare this to learning how to day trade, it’s still essential to understand intellectually the concepts of risk management, technical analysis and trading strategy, even though the understanding on its own isn’t adequate.

Here in March 2022, we’re at another point where there’s elevated potential of a sustained bear market. We’re not making a market call here, instead, we’re simply being realistic that today’s market conditions present a higher likelihood than prior to finally end the bull market in stocks.

In fashion with the potentially changing times, we’re going over some not only to identify, but adapt to changing market conditions.

Where We’re At Today: Commodities Are Key

For one, lockdowns created massive supply chain constraints.

Early on, many production facilities shutdown and workers were out of work and forced to collect unemployment benefits, which received huge stimulus boosts, often offering similar wages to their jobs.

As such, when production began to ramp back up, workers were disincentivized from returning, creating labor shortages, which further exacerbated goods shortages. Furthermore, the threat of rolling lockdowns loomed on these facilities.

On the raw commodities front, one of the most pressing shortages was that of oil. The initial downward price shocks that occurred hand-in-hand with the stock market crash of March 2020 forced many energy companies to clamp down as none of their operations were profitable with such low oil prices.

Combined with structural underinvestment in oil as a result of overbuilding of non-economic projects during the shale boom, and due to constraints from both institutional finance and government, effectively locked the energy industry out of a large pool of capital, so the US energy industry was underbuilt prior to the 2020 oil crisis.

Now with the increased tensions between the US and Russia, there’s significant talks of halting all imports of Russian energy in both the US and Europe, which of course would lead to higher domestic energy prices in the short-to-intermediate-term, as ramping up US energy production is a process that takes years, not weeks.

Raw commodities like oil, copper, lumber, wheat, cattle and so on are key inputs to nearly every good in our economy. The price of wheat going up means Wonder Bread, flour, and most packaged snacks cost more.

Bloomberg Commodity Index – Weekly Chart since late 2019

However, the most consequential commodity here is oil. Oil is an input cost in nearly everything at all stages along the supply chain. During production, the machines need to be run, the goods need to be transported, the grocery store needs to be heated or cooled. The price of oil trickles down to everything, which is why crude oil prices and inflation move together historically.

Coupled with this commodity supply crisis is the fact that the Federal Reserve has kept rates artificially low for such a long time – as real rates are zero right now. In order to quell inflation, the Fed is being forced to hike rates and offload their balance sheet into a shaky economic situation.

For these reasons, many smart macro strategists are preparing for a potential sustained bear market in US equities. But on the other side of the coin, many have pointed out that stocks tend to perform quite well in periods of very high inflation. Like we said, this isn’t a market call, but a brief on what people are thinking. If they’re right, we can at least be prepared.

Identifying the Market Regime and Know If It’s Changing

What is a Market Regime?

Within a bull market, many different market regimes come to dominate, fade away, and return. Just as over the last several decades, US stocks are marked by a boom-bust cycle, that too exists in fractal form within each bull and bear market.

Each bull market has its own set of periods where highly volatile bearish conditions persist, or when euphoric bullishness is sky-high and tons of blow-off tops are sprouting up across the stock market.

Two Sigma, the massive quant trading firm, defined market regimes like this:

“Financial markets have the tendency to change their behavior over time, which can create regimes or periods of fairly persistent market conditions…Modeling various market regimes…can enable macroeconomically aware investment decision-making and better management of tail risks” – Two Sigma

Two Sigma

These persisting market conditions within a larger macro framework are known as market regimes, and identifying the current market regime and trading in-tune with it is paramount to success.

One simple way to do this would be to simply break things down into simple categories:

- Uptrend

- Range-bound

- Downtrend

This is simple, but effective. Another way to do this would be to get a bit more specific, as Chris Dover from Macro-Ops does in his framework:

- Bull Quiet: long-bias

- Bull Volatile: blow-off top territory, generally avoid

- Neutral: mean reversion bias

- Bear Quiet: short-bias

- Bear Volatile:

I like the inclusion of volatility when categorizing market regimes, as it indicates uncertainty on the part of the market. When the market is just steadily trending up or down, it’s a completely different environment than when you sprinkle some volatility in. During times of a high VIX, traders indiscriminately dump the previous regime’s darlings and aggressively buy what they think the next play is. You can broadly call regimes with volatility or the lack thereof as risk-on (low vol), and risk-off (high vol).

Other traders would use macroeconomic analysis involving interest rates, inflation, what the Federal Reserve is saying, etc., however that’s not our style, we mostly stick to price action here, although all lenses which allow you to see that the dominant conditions of a market change are valid.

Market Regimes Lend to Different Trading Setups

Certain trading setups are ideal in each market regime. For example, a trend pullback or bull flag setup works excellently within a Bull Quiet regime, which features a healthy market which is mostly trading within trading bands like Bollinger Bands or Keltner Channels, and makes a stair step pattern of upswings and muted downswings.

Bull volatile regimes tend to lend well to breakout trading, which aims to capitalize on the break of a trading range for large wins and small losses.

Neutral market regimes tend to feature a range-bound, indecisive market which lends itself well to mean reversion trading.

Using Your Own Trading Data To Identify Regimes

Sure, you can use a number of technical and economic indicators to identify the current market regime, but those are ultimately just backwards looking calculations. A much better source of information is your own trading results.

To do this, however, you need to be recording your trades and categorizing them according to setup. Tools like TraderVue, EdgeWonk, and FundSeeder analytics are great for this purpose.

How are your pullback trades performing lately? If their performance is steadily declining when the norm is for them to perform well, you might be shifting away from the current market regime into a new one. If you really want to get fancy, you can overlay the equity curve of your setup against the broad market you trade. If you trade mostly energy stocks, you can compare the equity curve to something like $XOP or $XLE.

The most valuable data is from your own trading, not from a backtest or theoretical data from an academic study. That stuff is useful, but it pales in comparison to actual data the market gave you based on your own trading.

Using Range to Your Advantage

A telltale sign of a shifting market regime is range expansion. As the market gets wind of the changing tide, traders rush to reposition themselves to profit from the new paradigm. This creates volatility, as many traders are trading with constraints on them; in other words, their mandate might force them to trade even though right now wouldn’t be the optimal time to trade.

Markets move in cycles of range expansion and range contraction under normal conditions, however, so an expansion of range in itself isn’t significant. It has to be range expansion that breaks the intermediate-term cycle.

Most portfolio managers use the S&P 500 Volatility Index (VIX) to identify this. The problem here is that the VIX doesn’t paint a clear picture. It’s an index used as a reference price for so many securities and is used for hedging so much that it can distort today’s reality. Instead, it’s better to keep things simple and use a tool like Average True Range which tells you flat out how range is changing based on price action.

For example, here is a chart of SPY with a 14-day Average True Range line on the bottom:

When volatility is elevating, it might be indicating that there’s a regime shift afoot. We often see the crackles in the floor before the earthquake starts.

Adapting: Shorting Is Different

The stock market puts far more constraints on short sellers than contract-based markets like options or futures. This is because of the market structure of the stock market: you have to borrow shares to sell them short, while to short in the futures market, a new contract is simply created between you and your counterparty. There’s no disparity, neither party has an inherent advantage as longs do in the stock market.

For the uninitiated, here is roughly how the mechanics of short selling stocks works in the US market:

- You make a request to your broker to borrow 100 shares of $XYZ to sell short

- Your broker checks its inventory (its customers long holdings)

- If your broker has the shares in its inventory, it simply lends them to you for a commensurate interest rate

- If your broker does not have the shares available, it calls other securities lending desks and secures a borrow. That desk lends your broker the shares for a price, and your broker essentially flips that borrow to you for an elevated interest rate; arbitrage.

- Once the shares are in your custody, you can sell the stock short, with the promise to return the shares back to your broker at a later date.

- Your P&L is the difference between when you sold the stock short initially, and how much you bought it back for.

Many times, there’s not even a borrow available for you to short the stock, at least at your brokerage firm. This is because your broker has to have the shares in its custody to lend them to you, you’re actually taking out a loan to borrow stock and paying interest when you short sell a stock.

Beyond that, the best stocks to short (the obvious zeroes) often have very high interest rates if you can even secure a borrow. This partly explains why some obviously bad companies can have an elevated price for an unbelievable amount of time: it costs too much to short them. And the borrow rates are baked into the option pricing too, so buying puts isn’t a way around this (no free lunch).

With this in mind, there’s an adverse selection at play when shorting stocks, especially as a retail trader (retail has inferior access to borrows). The stocks that you can short (can locate shares to short) are less likely to be the best short candidates simply because there’s not high demand to short them, and hence, the market doesn’t agree with your thesis.

This is one of the first issues that long-only traders tackle when they correctly identify a bear market and try to start shorting stocks using the same setups they do to buy them. But the primary problem comes down to how stocks move.

One of the most fitting and true quotes is that “stocks take the stairs on the way up, and the elevator on the way down.” A stock can steadily go from $20 to $50 over the course of two years, only for it to crash back to $20 in two days. Only on the rarest occasions does this happen on the way up.

So, in other words, you must adapt your bearish trading setups on the way down, especially when things are volatile.

Constraints to Short Selling:

- Paying borrow interest rates

- Potentially paying locate fees

- Your shares could be called due at any time

- You could be forced out of your position if a party controls a large percentage of the float

Adapting: Know When To Get Aggressive

As traders we love to obsess over risk management; being very clinical in adjusting and hedging our positions as market dynamics change so we never get too exposed to any one factor. However, sometimes you can get so wrapped up in sticking to your system that you miss a goldmine sitting right under your nose.

One of my favorite interviews on the excellent podcast Chat With Traders is with Peter To, a former prop trader. Whenever I go back and listen, I always really appreciate when Peter talks about his “trading nihilism,” in which he’s concluded there’s no completely correct way to trade:

“In my old prop firm, the best day they ever had, by far, was buying the flash crash in 2012. And they put the firm in jeopardy. Their attitude was ‘it was someone else’s money,’ and they were like ‘screw it, the market’s wrong,’ we’re just gonna do it and make it a bunch of money and that ended up being their best day.

What can you say to that from a judgment on their risk management, is that right or wrong? DId they get lucky, was it skill? There’s no right answer. That’s the difference between gambling and poker. In gambling you have this mathematical framework that says ‘this decision is wrong, making this bet is right, and so on.’ You don’t have that in trading. You can get lost in wondering if this once in a lifetime trade that will never repeat itself for you, whether you played it the right way or not. It’s not a blackjack hand that you can simulate a bunch of times.”

Now, it’s never a good idea to put your account or firm at risk. But that’s not what Peter meant.

He was calling out the trading book culture of never deviating at all from your system and bringing in your own common sense for fear of making irrational decisions. Quick thought experiment: you have two potential trades, one is a flash crash-like event and the other is your average everyday breakout or flag setup. Are you really going to allocate the same risk to both trades?

Adapting: Look at Leadership

The start of the Russia and Ukraine war marked a significant regime shift in the US markets. It was immediately clear that things were changing when formerly dormant stocks in agriculture, coal, oil & gas, etc. became market leaders while the Wall Street growth darlings like Peloton and PayPal were getting pummeled.

An easy distinction you can make is look at what moves on the volatile days. There are two basic categories that stocks fall into: cyclical and defensive. Cyclical stocks do very well during a bull market and their outperformance is indicative of a ‘risk-on’ market regime. These are stocks from the following sectors:

- Technology

- Consumer discretionary

- Financials

- Healthcare

- Real estate

On the other hand you have defensive stocks. They’re the economic essentials. They don’t make crazy gains during a bull market but they go down far less when things get tough. Their outperformance indicates a risk-off environment. They’re in these sectors:

- Consumer staples

- Industrials

- Basic materials

- Utilities

These are broad distinctions and oftentimes they’re misleading, however. Once you get familiar with most larger-cap names, it’ll become pretty obvious what’s going on. When the defense contractors are going up and Peloton is going down, it’s clearly a risk-off price reaction.

You should be constantly assessing the market leaders, in terms of relative strength, and see where the money is flowing. There’s a number of ways to do this. First, is to simply use a relative strength percentile measure, which is available from many services like Investor’s Business Daily and StockCharts.

Another way is to look at the flows of funds. Flow of funds data often doesn’t show up on the chart, it shows a different picture of supply and demand. ETF flows are great for this, as the data is freely available from ETF.com. But what I really like is looking at the net selling or buying done at the market close through market-on-close imbalances.

Market Chameleon is one service that I know of that collects and organizes the data. It shows you a cumulative 20-day average of how much money is flowing in or out of a sector during the closing auction.

Bottom Line

What was surprising about the March 2020 crash was how many retail and smaller traders absolutely killed the trade compared to their institutional counterparts who fared much worse on the aggregate. I’ve met so many traders that had dry powder and put it all to work near the lows.

It’s clear that the idea of “buy when there’s blood in the streets” has gone fully mainstream at this point, which explains the super fast V-shaped recovery we saw in the market’s last crash.

But a key thing to keep in mind is that the next crash is never exactly like the last. You can’t just take out the March 2020 playbook and start blindly buying whatever the hot industry of the crash is.

That ultimately might be the answer, but especially in times of crazy volatility, you need to give yourself the time to consider second and third-order consequences of the crash, because that’s what the guys who killed the work-from-home trade got right. Rather than focusing on speculative vaccine stocks, they were buying Amazon and Zoom.

The post How To Adjust to Changing Market Conditions appeared first on Warrior Trading.

unemployment pandemic stimulus sp 500 equities stocks fed federal reserve real estate etf vaccine recovery interest rates unemployment stimulus commodities oil europe russia ukraineInternational

The next pandemic? It’s already here for Earth’s wildlife

Bird flu is decimating species already threatened by climate change and habitat loss.

I am a conservation biologist who studies emerging infectious diseases. When people ask me what I think the next pandemic will be I often say that we are in the midst of one – it’s just afflicting a great many species more than ours.

I am referring to the highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza H5N1 (HPAI H5N1), otherwise known as bird flu, which has killed millions of birds and unknown numbers of mammals, particularly during the past three years.

This is the strain that emerged in domestic geese in China in 1997 and quickly jumped to humans in south-east Asia with a mortality rate of around 40-50%. My research group encountered the virus when it killed a mammal, an endangered Owston’s palm civet, in a captive breeding programme in Cuc Phuong National Park Vietnam in 2005.

How these animals caught bird flu was never confirmed. Their diet is mainly earthworms, so they had not been infected by eating diseased poultry like many captive tigers in the region.

This discovery prompted us to collate all confirmed reports of fatal infection with bird flu to assess just how broad a threat to wildlife this virus might pose.

This is how a newly discovered virus in Chinese poultry came to threaten so much of the world’s biodiversity.

The first signs

Until December 2005, most confirmed infections had been found in a few zoos and rescue centres in Thailand and Cambodia. Our analysis in 2006 showed that nearly half (48%) of all the different groups of birds (known to taxonomists as “orders”) contained a species in which a fatal infection of bird flu had been reported. These 13 orders comprised 84% of all bird species.

We reasoned 20 years ago that the strains of H5N1 circulating were probably highly pathogenic to all bird orders. We also showed that the list of confirmed infected species included those that were globally threatened and that important habitats, such as Vietnam’s Mekong delta, lay close to reported poultry outbreaks.

Mammals known to be susceptible to bird flu during the early 2000s included primates, rodents, pigs and rabbits. Large carnivores such as Bengal tigers and clouded leopards were reported to have been killed, as well as domestic cats.

Our 2006 paper showed the ease with which this virus crossed species barriers and suggested it might one day produce a pandemic-scale threat to global biodiversity.

Unfortunately, our warnings were correct.

A roving sickness

Two decades on, bird flu is killing species from the high Arctic to mainland Antarctica.

In the past couple of years, bird flu has spread rapidly across Europe and infiltrated North and South America, killing millions of poultry and a variety of bird and mammal species. A recent paper found that 26 countries have reported at least 48 mammal species that have died from the virus since 2020, when the latest increase in reported infections started.

Not even the ocean is safe. Since 2020, 13 species of aquatic mammal have succumbed, including American sea lions, porpoises and dolphins, often dying in their thousands in South America. A wide range of scavenging and predatory mammals that live on land are now also confirmed to be susceptible, including mountain lions, lynx, brown, black and polar bears.

The UK alone has lost over 75% of its great skuas and seen a 25% decline in northern gannets. Recent declines in sandwich terns (35%) and common terns (42%) were also largely driven by the virus.

Scientists haven’t managed to completely sequence the virus in all affected species. Research and continuous surveillance could tell us how adaptable it ultimately becomes, and whether it can jump to even more species. We know it can already infect humans – one or more genetic mutations may make it more infectious.

At the crossroads

Between January 1 2003 and December 21 2023, 882 cases of human infection with the H5N1 virus were reported from 23 countries, of which 461 (52%) were fatal.

Of these fatal cases, more than half were in Vietnam, China, Cambodia and Laos. Poultry-to-human infections were first recorded in Cambodia in December 2003. Intermittent cases were reported until 2014, followed by a gap until 2023, yielding 41 deaths from 64 cases. The subtype of H5N1 virus responsible has been detected in poultry in Cambodia since 2014. In the early 2000s, the H5N1 virus circulating had a high human mortality rate, so it is worrying that we are now starting to see people dying after contact with poultry again.

It’s not just H5 subtypes of bird flu that concern humans. The H10N1 virus was originally isolated from wild birds in South Korea, but has also been reported in samples from China and Mongolia.

Recent research found that these particular virus subtypes may be able to jump to humans after they were found to be pathogenic in laboratory mice and ferrets. The first person who was confirmed to be infected with H10N5 died in China on January 27 2024, but this patient was also suffering from seasonal flu (H3N2). They had been exposed to live poultry which also tested positive for H10N5.

Species already threatened with extinction are among those which have died due to bird flu in the past three years. The first deaths from the virus in mainland Antarctica have just been confirmed in skuas, highlighting a looming threat to penguin colonies whose eggs and chicks skuas prey on. Humboldt penguins have already been killed by the virus in Chile.

How can we stem this tsunami of H5N1 and other avian influenzas? Completely overhaul poultry production on a global scale. Make farms self-sufficient in rearing eggs and chicks instead of exporting them internationally. The trend towards megafarms containing over a million birds must be stopped in its tracks.

To prevent the worst outcomes for this virus, we must revisit its primary source: the incubator of intensive poultry farms.

Diana Bell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

genetic pandemic mortality spread deaths south korea south america europe uk chinaInternational

This is the biggest money mistake you’re making during travel

A retail expert talks of some common money mistakes travelers make on their trips.

Travel is expensive. Despite the explosion of travel demand in the two years since the world opened up from the pandemic, survey after survey shows that financial reasons are the biggest factor keeping some from taking their desired trips.

Airfare, accommodation as well as food and entertainment during the trip have all outpaced inflation over the last four years.

Related: This is why we're still spending an insane amount of money on travel

But while there are multiple tricks and “travel hacks” for finding cheaper plane tickets and accommodation, the biggest financial mistake that leads to blown travel budgets is much smaller and more insidious.

This is what you should (and shouldn’t) spend your money on while abroad

“When it comes to traveling, it's hard to resist buying items so you can have a piece of that memory at home,” Kristen Gall, a retail expert who heads the financial planning section at points-back platform Rakuten, told Travel + Leisure in an interview. “However, it's important to remember that you don't need every souvenir that catches your eye.”

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

According to Gall, souvenirs not only have a tendency to add up in price but also weight which can in turn require one to pay for extra weight or even another suitcase at the airport — over the last two months, airlines like Delta (DAL) , American Airlines (AAL) and JetBlue Airways (JBLU) have all followed each other in increasing baggage prices to in some cases as much as $60 for a first bag and $100 for a second one.

While such extras may not seem like a lot compared to the thousands one might have spent on the hotel and ticket, they all have what is sometimes known as a “coffee” or “takeout effect” in which small expenses can lead one to overspend by a large amount.

‘Save up for one special thing rather than a bunch of trinkets…’

“When traveling abroad, I recommend only purchasing items that you can't get back at home, or that are small enough to not impact your luggage weight,” Gall said. “If you’re set on bringing home a souvenir, save up for one special thing, rather than wasting your money on a bunch of trinkets you may not think twice about once you return home.”

Along with the immediate costs, there is also the risk of purchasing things that go to waste when returning home from an international vacation. Alcohol is subject to airlines’ liquid rules while certain types of foods, particularly meat and other animal products, can be confiscated by customs.

While one incident of losing an expensive bottle of liquor or cheese brought back from a country like France will often make travelers forever careful, those who travel internationally less frequently will often be unaware of specific rules and be forced to part with something they spent money on at the airport.

“It's important to keep in mind that you're going to have to travel back with everything you purchased,” Gall continued. “[…] Be careful when buying food or wine, as it may not make it through customs. Foods like chocolate are typically fine, but items like meat and produce are likely prohibited to come back into the country.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic franceInternational

As the pandemic turns four, here’s what we need to do for a healthier future

On the fourth anniversary of the pandemic, a public health researcher offers four principles for a healthier future.

Anniversaries are usually festive occasions, marked by celebration and joy. But there’ll be no popping of corks for this one.

March 11 2024 marks four years since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

Although no longer officially a public health emergency of international concern, the pandemic is still with us, and the virus is still causing serious harm.

Here are three priorities – three Cs – for a healthier future.

Clear guidance

Over the past four years, one of the biggest challenges people faced when trying to follow COVID rules was understanding them.

From a behavioural science perspective, one of the major themes of the last four years has been whether guidance was clear enough or whether people were receiving too many different and confusing messages – something colleagues and I called “alert fatigue”.

With colleagues, I conducted an evidence review of communication during COVID and found that the lack of clarity, as well as a lack of trust in those setting rules, were key barriers to adherence to measures like social distancing.

In future, whether it’s another COVID wave, or another virus or public health emergency, clear communication by trustworthy messengers is going to be key.

Combat complacency

As Maria van Kerkove, COVID technical lead for WHO, puts it there is no acceptable level of death from COVID. COVID complacency is setting in as we have moved out of the emergency phase of the pandemic. But is still much work to be done.

First, we still need to understand this virus better. Four years is not a long time to understand the longer-term effects of COVID. For example, evidence on how the virus affects the brain and cognitive functioning is in its infancy.

The extent, severity and possible treatment of long COVID is another priority that must not be forgotten – not least because it is still causing a lot of long-term sickness and absence.

Culture change

During the pandemic’s first few years, there was a question over how many of our new habits, from elbow bumping (remember that?) to remote working, were here to stay.

Turns out old habits die hard – and in most cases that’s not a bad thing – after all handshaking and hugging can be good for our health.

But there is some pandemic behaviour we could have kept, under certain conditions. I’m pretty sure most people don’t wear masks when they have respiratory symptoms, even though some health authorities, such as the NHS, recommend it.

Masks could still be thought of like umbrellas: we keep one handy for when we need it, for example, when visiting vulnerable people, especially during times when there’s a spike in COVID.

If masks hadn’t been so politicised as a symbol of conformity and oppression so early in the pandemic, then we might arguably have seen people in more countries adopting the behaviour in parts of east Asia, where people continue to wear masks or face coverings when they are sick to avoid spreading it to others.

Although the pandemic led to the growth of remote or hybrid working, presenteeism – going to work when sick – is still a major issue.

Encouraging parents to send children to school when they are unwell is unlikely to help public health, or attendance for that matter. For instance, although one child might recover quickly from a given virus, other children who might catch it from them might be ill for days.

Similarly, a culture of presenteeism that pressures workers to come in when ill is likely to backfire later on, helping infectious disease spread in workplaces.

At the most fundamental level, we need to do more to create a culture of equality. Some groups, especially the most economically deprived, fared much worse than others during the pandemic. Health inequalities have widened as a result. With ongoing pandemic impacts, for example, long COVID rates, also disproportionately affecting those from disadvantaged groups, health inequalities are likely to persist without significant action to address them.

Vaccine inequity is still a problem globally. At a national level, in some wealthier countries like the UK, those from more deprived backgrounds are going to be less able to afford private vaccines.

We may be out of the emergency phase of COVID, but the pandemic is not yet over. As we reflect on the past four years, working to provide clearer public health communication, avoiding COVID complacency and reducing health inequalities are all things that can help prepare for any future waves or, indeed, pandemics.

Simon Nicholas Williams has received funding from Senedd Cymru, Public Health Wales and the Wales Covid Evidence Centre for research on COVID-19, and has consulted for the World Health Organization. However, this article reflects the views of the author only, in his academic capacity at Swansea University, and no funding or organizational bodies were involved in the writing or content of this article.

vaccine treatment pandemic covid-19 spread social distancing uk world health organization-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex