Examining the uneven and hard-to-predict labor market recovery

With vaccination rates increasing and COVID-19 case rates declining, there is an urgency to get back to normal. The April 2021 employment report was a timely reminder that not everyone will experience the recovery from this crisis the same way – or…

By Lauren Bauer, Arindrajit Dube, Wendy Edelberg, Aaron Sojourner

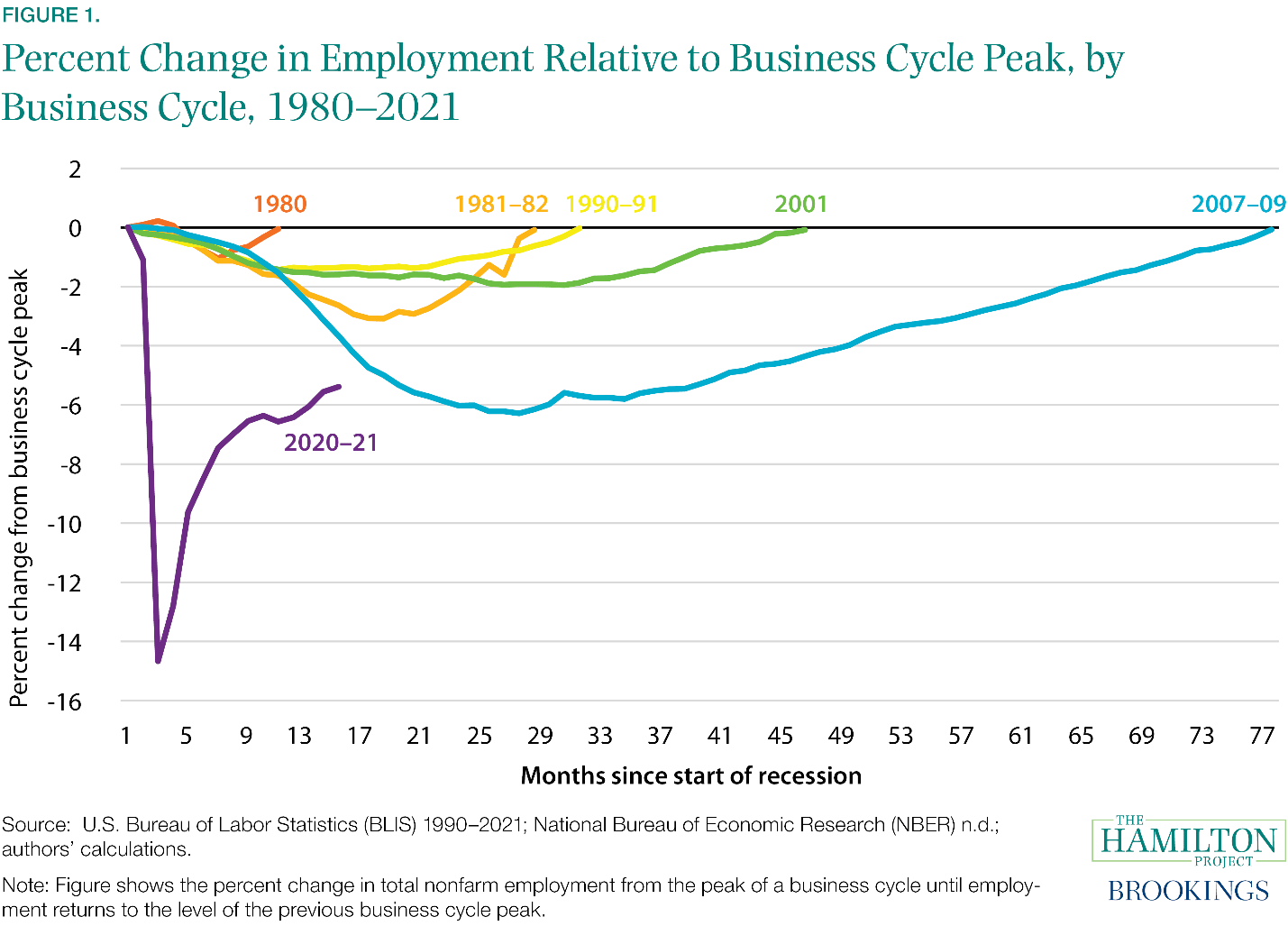

With vaccination rates increasing and COVID-19 case rates declining, there is an urgency to get back to normal. The April 2021 employment report was a timely reminder that not everyone will experience the recovery from this crisis the same way – or quickly. The post-pandemic shortfall in employment was over 10 million jobs relative to where the labor market would be in absence of the recession. Despite the relatively large average gains over February and March (653,000 jobs created), net employment gains slowed in April, surprising most observers (see figure 1). While any single monthly estimate is noisy, the last month’s news from the labor market seemed inconsistent with what we have seen in consumer spending; indeed, total vehicle sales were higher in April than in the last 16 years.

In the May 2021 employment report to be released tomorrow, which will provide information on the health of the labor market in mid-May, we expect to see continued improvement across several margins. We expect flows into employment to be strong and we will be looking at whether flows out of employment begin to taper (in line with the decline in new unemployment insurance claims). We will focus closely on rates of labor force participation to see if constraints holding back labor supply continue to ebb. Finally, we will look closely at measures of labor demand such as hours worked and overtime, as well as wages, to see what steps firms are taking to attract workers across sectors.

In this analysis, we outline factors that we think have slowed and will continue to slow net employment gains as the post-COVID economy reconstitutes itself. We note evidence of substantial churn in and out of jobs, including workers leaving what may have been temporary pandemic-related jobs: people leaving employment without moving immediately into a new position reduces net employment gains in a given month. We then describe some of the broad factors that may be holding people back from participating in the labor force, including fiscal policy. As an example of one factor having a significant effect on a narrower group, we show that caregiving responsibilities are dampening the labor supply of mothers whose youngest or oldest child is between the ages of 5 and 12 in states with a higher degree of elementary school closures.

Changing composition of work

The employment report released in early May showed a remarkable amount of churn in the labor market in April. Generally speaking, when we talk about the change in employment in any given month – for example April saw an increase of 266,000 – that number is the net of big flows in and out of employment. In April 2021, 6.6 million people went from being employed to unemployed or out of the labor force, while 6.7 million moved from unemployment or nonparticipation to employment. Those numbers sound big, but how big are they are relative to the last few months and relative to more normal times? The flow out of employment is higher than since December 2020: The average from January 2021 to March 2021 was 6.3 million. So, 300,000 more people left employment in April 2021 than on average over the preceding three months.

And, what were those outflows like pre-pandemic? In April 2019 and indeed on average over that whole year – 6.1 million people flowed out of employment. Think of the difference of 500,000 this way:

If employment had been as “sticky” in April 2021 as it was pre-pandemic, and flows into employment were as we observed them (considerably higher than pre-pandemic), the increase in employment might have been more like 800,000 – close to consensus expectations for April.

So, how do we interpret this increase in the flow out of employment? We have circumstantial evidence that it represents a transition from a pandemic labor force to a post-pandemic labor force.

New business formation was extraordinarily strong during the pandemic even as hundreds of thousands of businesses failed.

In 2019, Census reported that about 110,000 applications a month were filed among new business likely to employ people. Applications fell off notably early in the pandemic. Then, in July 2020, they spiked at over 190,000, and have averaged about 150,000 since. It stands to reason that many of these applications have reflected short-term business ventures dedicated to pandemic-related activity.

In addition, the changing composition of consumer demand suggests we are beginning to transition to a post-pandemic economy. For example, sales at grocery stores surged for months at the beginning of the pandemic but were much softer in March and April 2021. Meanwhile, restaurants saw very large increases in sales in those two months relative to 2020. The changing composition of demand will no doubt bring along with it a changing composition in the demand for workers. As some sectors try to rebound quickly and others fall back closer to pre-pandemic levels, the large swings in which sectors have vacancies may slow down job finding rates. As dynamic as the US labor market is, we should expect some bumps in the road as we transition to the post-pandemic economy.

The share of workers quitting jobs every month is quite high, suggesting the vacancies workers have been filling were not long-term matches.

The dynamism in the US labor market is evident in the percentage of workers who are quitting their jobs. From the fall through March 2021, that percentage has been back to pre-pandemic levels (2.4 percent), when the labor market was quite strong. Workers appear to be moving from job to job, trying to keep up with the changing composition of labor demand and trying to find a better, more productive match.

Factors holding back labor supply and employment gains

Participation in the labor market (those who are working plus those who are unemployed and actively seeking work) has recovered somewhat from pandemic lows but remains weak. An open question is how much stronger employment gains would be if participation were higher – or whether we would just see more people being categorized as unemployed instead of out of the labor force. Strong wage gains in some sectors and for some groups as well as a lot of anecdotal reporting suggests that certain firms are having a difficult time finding workers. Three questions emerge:

For how long might the large compositional issues described above lead to flows out of employment?

Fiscal support in the form of unemployment insurance benefits and other increases in transfers may be affecting the transition described above. Two potential channels could be at work, although we have no evidence suggesting either is currently a significant factor. First, layoffs by firms are likely facilitated by firms’ knowledge that most laid off workers will qualify for expanded unemployment insurance. Second, some workers quitting their jobs for “good cause” may also qualify for such benefits, making them more likely to quit and look for a better match. On the one hand, the availability of UI benefits means that workers will have time to find a good labor market match (and perhaps take a needed moment after a very difficult year). Indeed, the pandemic laid bare some of the worst aspects of working in certain sectors, giving workers an impetus to change industries. So, the recovery might be slower by a few months as a result but ultimately result in a more productive economy. On the other hand, the longer this transition takes and workers remain without employment, the more skills and labor force attachment deteriorate.

To the degree reduced labor force participation is holding back the recovery, how much of that is due to factors unique to coming back from a pandemic-caused recession?

Fiscal support is helping people prioritize their health over labor market income—certainly one of the goals when the support was put in place. That dampening effect on labor market participation should dissipate as we continue to vaccinate the population and beat back the pandemic.

From mid-April to mid-May 2021 the share of working age Americans (18-64 years old) who were at least two weeks past their final COVID vaccination dose more than doubled; but still only about 3 in 10 had achieved full immunization by that time (see figure 2). We find that employment as a share of the population has grown faster in states with faster improvement in working-age vaccination rates. States that lag behind on working-age vaccination rates will likely slow the recovery in the national labor market.

Other factors unique to the pandemic are having acute effects on relatively narrow groups. For example, the employment-population ratios of mothers of elementary school age children – the demographic likely bearing the brunt of school closures – fell more than that of other mothers and their employment rates continue to lag behind others through the beginning of 2021. To be sure, the portion of the labor force pre-pandemic comprised of mothers with elementary-school aged children is small enough (at only 9 percent) that these relatively large declines do not account for much of the weakness in labor force participation and employment in aggregate. Consequently, addressing child care will not come close to – on its own – making up lost ground in labor force participation. In addition, some explain this finding by examining the industries in which these mothers typically work, since their employment tends to be concentrated in industries that saw relatively large declines in employment. Nonetheless, the challenges for these parents are acutely felt and solvable.

We find that in states with relatively high levels of elementary school closures, the nearly 5 percentage point drop in the employment-population ratio for mothers with children age 5 to 12 is more than fully accounted for by having elementary school age children instead of teenagers (figures 3). We use school closure data to group states into those with population-weighted high and low closure rates. We then – looking at whether a mother’s oldest or youngest child is between the ages of 5 and 12 and school closure rates – examine the declines in the employment-to-population ratios from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021 (after adjusting for the misclassification errors that were particularly significant early in the pandemic and accounting for mother’s age, level of education, race/ethnicity, marital status, and region). We note that in high-elementary-school-closure-states, the recovery in the labor market for mothers of teens is almost complete, whereas that for mothers of teens in low-closure-states lags. In both types of states, we find that employment outcomes were statistically significantly worse for mothers having a youngest or oldest child 5 to 12 instead of the youngest being a teenager.

However, we find a larger (as shown in the figure) and more statistically significant effect (not shown) in states with more closures: if mothers of 5-12 year olds in high-closure states had instead been mothers to teens, we estimate that their employment-population ratio would have been roughly unchanged rather than falling nearly 5 percentage points.

What role has fiscal policy played and will continue to play in supporting or stalling the recovery?

Much has been written about whether the generous unemployment insurance benefits are temporarily slowing the job finding rate exclusive of any concerns about health risks, child care issues, or other factors making it challenging to work right now. Analysis by economists at the San Francisco Fed finds that the effects are modest. As mentioned above, one consequence of that effect could be a greater loss of skills and labor force attachment—along with bottlenecks in hiring. However, another effect could be better and ultimately more productive labor market matches, particularly in states where the labor market recovery has been slower. Regardless – any effects of expanded unemployment insurance benefits on labor supply will dissipate quickly as the benefits expire nationally in early September and before then in an increasing number of states. Indeed, policymakers should be on high-alert for whether the expiration of those benefits results in extraordinary financial hardship for some workers unable to find jobs.

Conclusion

There are many signs that the U.S. labor market is on the mend. For example, the average net increase in payroll employment from February to April was over 500,000. Initial unemployment insurance claims continue to decline. The number of unemployed people per job opening has fallen sharply. Teens are working in the labor market at higher rates than at any time in the past decade.

Nonetheless, policymakers must be vigilant — continuing to increase easy access to vaccines and helping to make working safe and rewarding. Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for childless adults will help to draw in labor market participants from the sidelines. School and child-care reopening will help those groups acutely affected. Still, the labor market recovery will undoubtedly be uneven. Some people and some sectors will continue to require fiscal support before we emerge from the crisis.

recession unemployment pandemic covid-19 reopening fed recovery consumer spending unemploymentSpread & Containment

Vaccine-skeptical mothers say bad health care experiences made them distrust the medical system

Vaccine skepticism, and the broader medical mistrust and far-reaching anxieties it reflects, is not just a fringe position in the 21st century.

Why would a mother reject safe, potentially lifesaving vaccines for her child?

Popular writing on vaccine skepticism often denigrates white and middle-class mothers who reject some or all recommended vaccines as hysterical, misinformed, zealous or ignorant. Mainstream media and medical providers increasingly dismiss vaccine refusal as a hallmark of American fringe ideology, far-right radicalization or anti-intellectualism.

But vaccine skepticism, and the broader medical mistrust and far-reaching anxieties it reflects, is not just a fringe position.

Pediatric vaccination rates had already fallen sharply before the COVID-19 pandemic, ushering in the return of measles, mumps and chickenpox to the U.S. in 2019. Four years after the pandemic’s onset, a growing number of Americans doubt the safety, efficacy and necessity of routine vaccines. Childhood vaccination rates have declined substantially across the U.S., which public health officials attribute to a “spillover” effect from pandemic-related vaccine skepticism and blame for the recent measles outbreak. Almost half of American mothers rated the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine as medium or high in a 2023 survey by Pew Research.

Recommended vaccines go through rigorous testing and evaluation, and the most infamous charges of vaccine-induced injury have been thoroughly debunked. How do so many mothers – primary caregivers and health care decision-makers for their families – become wary of U.S. health care and one of its most proven preventive technologies?

I’m a cultural anthropologist who studies the ways feelings and beliefs circulate in American society. To investigate what’s behind mothers’ vaccine skepticism, I interviewed vaccine-skeptical mothers about their perceptions of existing and novel vaccines. What they told me complicates sweeping and overly simplified portrayals of their misgivings by pointing to the U.S. health care system itself. The medical system’s failures and harms against women gave rise to their pervasive vaccine skepticism and generalized medical mistrust.

The seeds of women’s skepticism

I conducted this ethnographic research in Oregon from 2020 to 2021 with predominantly white mothers between the ages of 25 and 60. My findings reveal new insights about the origins of vaccine skepticism among this demographic. These women traced their distrust of vaccines, and of U.S. health care more generally, to ongoing and repeated instances of medical harm they experienced from childhood through childbirth.

As young girls in medical offices, they were touched without consent, yelled at, disbelieved or threatened. One mother, Susan, recalled her pediatrician abruptly lying her down and performing a rectal exam without her consent at the age of 12. Another mother, Luna, shared how a pediatrician once threatened to have her institutionalized when she voiced anxiety at a routine physical.

As women giving birth, they often felt managed, pressured or discounted. One mother, Meryl, told me, “I felt like I was coerced under distress into Pitocin and induction” during labor. Another mother, Hallie, shared, “I really battled with my provider” throughout the childbirth experience.

Together with the convoluted bureaucracy of for-profit health care, experiences of medical harm contributed to “one million little touch points of information,” in one mother’s phrase, that underscored the untrustworthiness and harmful effects of U.S. health care writ large.

A system that doesn’t serve them

Many mothers I interviewed rejected the premise that public health entities such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration had their children’s best interests at heart. Instead, they tied childhood vaccination and the more recent development of COVID-19 vaccines to a bloated pharmaceutical industry and for-profit health care model. As one mother explained, “The FDA is not looking out for our health. They’re looking out for their wealth.”

After ongoing negative medical encounters, the women I interviewed lost trust not only in providers but the medical system. Frustrating experiences prompted them to “do their own research” in the name of bodily autonomy. Such research often included books, articles and podcasts deeply critical of vaccines, public health care and drug companies.

These materials, which have proliferated since 2020, cast light on past vaccine trials gone awry, broader histories of medical harm and abuse, the rapid growth of the recommended vaccine schedule in the late 20th century and the massive profits reaped from drug development and for-profit health care. They confirmed and hardened women’s suspicions about U.S. health care.

The stories these women told me add nuance to existing academic research into vaccine skepticism. Most studies have considered vaccine skepticism among primarily white and middle-class parents to be an outgrowth of today’s neoliberal parenting and intensive mothering. Researchers have theorized vaccine skepticism among white and well-off mothers to be an outcome of consumer health care and its emphasis on individual choice and risk reduction. Other researchers highlight vaccine skepticism as a collective identity that can provide mothers with a sense of belonging.

Seeing medical care as a threat to health

The perceptions mothers shared are far from isolated or fringe, and they are not unreasonable. Rather, they represent a growing population of Americans who hold the pervasive belief that U.S. health care harms more than it helps.

Data suggests that the number of Americans harmed in the course of treatment remains high, with incidents of medical error in the U.S. outnumbering those in peer countries, despite more money being spent per capita on health care. One 2023 study found that diagnostic error, one kind of medical error, accounted for 371,000 deaths and 424,000 permanent disabilities among Americans every year.

Studies reveal particularly high rates of medical error in the treatment of vulnerable communities, including women, people of color, disabled, poor, LGBTQ+ and gender-nonconforming individuals and the elderly. The number of U.S. women who have died because of pregnancy-related causes has increased substantially in recent years, with maternal death rates doubling between 1999 and 2019.

The prevalence of medical harm points to the relevance of philosopher Ivan Illich’s manifesto against the “disease of medical progress.” In his 1982 book “Medical Nemesis,” he insisted that rather than being incidental, harm flows inevitably from the structure of institutionalized and for-profit health care itself. Illich wrote, “The medical establishment has become a major threat to health,” and has created its own “epidemic” of iatrogenic illness – that is, illness caused by a physician or the health care system itself.

Four decades later, medical mistrust among Americans remains alarmingly high. Only 23% of Americans express high confidence in the medical system. The United States ranks 24th out of 29 peer high-income countries for the level of public trust in medical providers.

For people like the mothers I interviewed, who have experienced real or perceived harm at the hands of medical providers; have felt belittled, dismissed or disbelieved in a doctor’s office; or spent countless hours fighting to pay for, understand or use health benefits, skepticism and distrust are rational responses to lived experience. These attitudes do not emerge solely from ignorance, conspiracy thinking, far-right extremism or hysteria, but rather the historical and ongoing harms endemic to the U.S. health care system itself.

Johanna Richlin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

disease control extremism pandemic covid-19 vaccine treatment testing fda deathsGovernment

Is the National Guard a solution to school violence?

School board members in one Massachusetts district have called for the National Guard to address student misbehavior. Does their request have merit? A…

Every now and then, an elected official will suggest bringing in the National Guard to deal with violence that seems out of control.

A city council member in Washington suggested doing so in 2023 to combat the city’s rising violence. So did a Pennsylvania representative concerned about violence in Philadelphia in 2022.

In February 2024, officials in Massachusetts requested the National Guard be deployed to a more unexpected location – to a high school.

Brockton High School has been struggling with student fights, drug use and disrespect toward staff. One school staffer said she was trampled by a crowd rushing to see a fight. Many teachers call in sick to work each day, leaving the school understaffed.

As a researcher who studies school discipline, I know Brockton’s situation is part of a national trend of principals and teachers who have been struggling to deal with perceived increases in student misbehavior since the pandemic.

A review of how the National Guard has been deployed to schools in the past shows the guard can provide service to schools in cases of exceptional need. Yet, doing so does not always end well.

How have schools used the National Guard before?

In 1957, the National Guard blocked nine Black students’ attempts to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. While the governor claimed this was for safety, the National Guard effectively delayed desegregation of the school – as did the mobs of white individuals outside. Ironically, weeks later, the National Guard and the U.S. Army would enforce integration and the safety of the “Little Rock Nine” on orders from President Dwight Eisenhower.

One of the most tragic cases of the National Guard in an educational setting came in 1970 at Kent State University. The National Guard was brought to campus to respond to protests over American involvement in the Vietnam War. The guardsmen fatally shot four students.

In 2012, then-Sen. Barbara Boxer, a Democrat from California, proposed funding to use the National Guard to provide school security in the wake of the Sandy Hook school shooting. The bill was not passed.

More recently, the National Guard filled teacher shortages in New Mexico’s K-12 schools during the quarantines and sickness of the pandemic. While the idea did not catch on nationally, teachers and school personnel in New Mexico generally reported positive experiences.

Can the National Guard address school discipline?

The National Guard’s mission includes responding to domestic emergencies. Members of the guard are part-time service members who maintain civilian lives. Some are students themselves in colleges and universities. Does this mission and training position the National Guard to respond to incidents of student misbehavior and school violence?

On the one hand, New Mexico’s pandemic experience shows the National Guard could be a stopgap to staffing shortages in unusual circumstances. Similarly, the guards’ eventual role in ensuring student safety during school desegregation in Arkansas demonstrates their potential to address exceptional cases in schools, such as racially motivated mob violence. And, of course, many schools have had military personnel teaching and mentoring through Junior ROTC programs for years.

Those seeking to bring the National Guard to Brockton High School have made similar arguments. They note that staffing shortages have contributed to behavior problems.

One school board member stated: “I know that the first thought that comes to mind when you hear ‘National Guard’ is uniform and arms, and that’s not the case. They’re people like us. They’re educated. They’re trained, and we just need their assistance right now. … We need more staff to support our staff and help the students learn (and) have a safe environment.”

Yet, there are reasons to question whether calls for the National Guard are the best way to address school misconduct and behavior. First, the National Guard is a temporary measure that does little to address the underlying causes of student misbehavior and school violence.

Research has shown that students benefit from effective teaching, meaningful and sustained relationships with school personnel and positive school environments. Such educative and supportive environments have been linked to safer schools. National Guard members are not trained as educators or counselors and, as a temporary measure, would not remain in the school to establish durable relationships with students.

What is more, a military presence – particularly if uniformed or armed – may make students feel less welcome at school or escalate situations.

Schools have already seen an increase in militarization. For example, school police departments have gone so far as to acquire grenade launchers and mine-resistant armored vehicles.

Research has found that school police make students more likely to be suspended and to be arrested. Similarly, while a National Guard presence may address misbehavior temporarily, their presence could similarly result in students experiencing punitive or exclusionary responses to behavior.

Students deserve a solution other than the guard

School violence and disruptions are serious problems that can harm students. Unfortunately, schools and educators have increasingly viewed student misbehavior as a problem to be dealt with through suspensions and police involvement.

A number of people – from the NAACP to the local mayor and other members of the school board – have criticized Brockton’s request for the National Guard. Governor Maura Healey has said she will not deploy the guard to the school.

However, the case of Brockton High School points to real needs. Educators there, like in other schools nationally, are facing a tough situation and perceive a lack of support and resources.

Many schools need more teachers and staff. Students need access to mentors and counselors. With these resources, schools can better ensure educators are able to do their jobs without military intervention.

F. Chris Curran has received funding from the US Department of Justice, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the American Civil Liberties Union for work on school safety and discipline.

army governor pandemic mexicoGovernment

Chinese migration to US is nothing new – but the reasons for recent surge at Southern border are

A gloomier economic outlook in China and tightening state control have combined with the influence of social media in encouraging migration.

The brief closure of the Darien Gap – a perilous 66-mile jungle journey linking South American and Central America – in February 2024 temporarily halted one of the Western Hemisphere’s busiest migration routes. It also highlighted its importance to a small but growing group of people that depend on that pass to make it to the U.S.: Chinese migrants.

While a record 2.5 million migrants were detained at the United States’ southwestern land border in 2023, only about 37,000 were from China.

I’m a scholar of migration and China. What I find most remarkable in these figures is the speed with which the number of Chinese migrants is growing. Nearly 10 times as many Chinese migrants crossed the southern border in 2023 as in 2022. In December 2023 alone, U.S. Border Patrol officials reported encounters with about 6,000 Chinese migrants, in contrast to the 900 they reported a year earlier in December 2022.

The dramatic uptick is the result of a confluence of factors that range from a slowing Chinese economy and tightening political control by President Xi Jinping to the easy access to online information on Chinese social media about how to make the trip.

Middle-class migrants

Journalists reporting from the border have generalized that Chinese migrants come largely from the self-employed middle class. They are not rich enough to use education or work opportunities as a means of entry, but they can afford to fly across the world.

According to a report from Reuters, in many cases those attempting to make the crossing are small-business owners who saw irreparable damage to their primary or sole source of income due to China’s “zero COVID” policies. The migrants are women, men and, in some cases, children accompanying parents from all over China.

Chinese nationals have long made the journey to the United States seeking economic opportunity or political freedom. Based on recent media interviews with migrants coming by way of South America and the U.S.’s southern border, the increase in numbers seems driven by two factors.

First, the most common path for immigration for Chinese nationals is through a student visa or H1-B visa for skilled workers. But travel restrictions during the early months of the pandemic temporarily stalled migration from China. Immigrant visas are out of reach for many Chinese nationals without family or vocation-based preferences, and tourist visas require a personal interview with a U.S. consulate to gauge the likelihood of the traveler returning to China.

Social media tutorials

Second, with the legal routes for immigration difficult to follow, social media accounts have outlined alternatives for Chinese who feel an urgent need to emigrate. Accounts on Douyin, the TikTok clone available in mainland China, document locations open for visa-free travel by Chinese passport holders. On TikTok itself, migrants could find information on where to cross the border, as well as information about transportation and smugglers, commonly known as “snakeheads,” who are experienced with bringing migrants on the journey north.

With virtual private networks, immigrants can also gather information from U.S. apps such as X, YouTube, Facebook and other sites that are otherwise blocked by Chinese censors.

Inspired by social media posts that both offer practical guides and celebrate the journey, thousands of Chinese migrants have been flying to Ecuador, which allows visa-free travel for Chinese citizens, and then making their way over land to the U.S.-Mexican border.

This journey involves trekking through the Darien Gap, which despite its notoriety as a dangerous crossing has become an increasingly common route for migrants from Venezuela, Colombia and all over the world.

In addition to information about crossing the Darien Gap, these social media posts highlight the best places to cross the border. This has led to a large share of Chinese asylum seekers following the same path to Mexico’s Baja California to cross the border near San Diego.

Chinese migration to US is nothing new

The rapid increase in numbers and the ease of accessing information via social media on their smartphones are new innovations. But there is a longer history of Chinese migration to the U.S. over the southern border – and at the hands of smugglers.

From 1882 to 1943, the United States banned all immigration by male Chinese laborers and most Chinese women. A combination of economic competition and racist concerns about Chinese culture and assimilability ensured that the Chinese would be the first ethnic group to enter the United States illegally.

With legal options for arrival eliminated, some Chinese migrants took advantage of the relative ease of movement between the U.S. and Mexico during those years. While some migrants adopted Mexican names and spoke enough Spanish to pass as migrant workers, others used borrowed identities or paperwork from Chinese people with a right of entry, like U.S.-born citizens. Similarly to what we are seeing today, it was middle- and working-class Chinese who more frequently turned to illegal means. Those with money and education were able to circumvent the law by arriving as students or members of the merchant class, both exceptions to the exclusion law.

Though these Chinese exclusion laws officially ended in 1943, restrictions on migration from Asia continued until Congress revised U.S. immigration law in the Hart-Celler Act in 1965. New priorities for immigrant visas that stressed vocational skills as well as family reunification, alongside then Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s policies of “reform and opening,” helped many Chinese migrants make their way legally to the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s.

Even after the restrictive immigration laws ended, Chinese migrants without the education or family connections often needed for U.S. visas continued to take dangerous routes with the help of “snakeheads.”

One notorious incident occurred in 1993, when a ship called the Golden Venture ran aground near New York, resulting in the drowning deaths of 10 Chinese migrants and the arrest and conviction of the snakeheads attempting to smuggle hundreds of Chinese migrants into the United States.

Existing tensions

Though there is plenty of precedent for Chinese migrants arriving without documentation, Chinese asylum seekers have better odds of success than many of the other migrants making the dangerous journey north.

An estimated 55% of Chinese asylum seekers are successful in making their claims, often citing political oppression and lack of religious freedom in China as motivations. By contrast, only 29% of Venezuelans seeking asylum in the U.S. have their claim granted, and the number is even lower for Colombians, at 19%.

The new halt on the migratory highway from the south has affected thousands of new migrants seeking refuge in the U.S. But the mix of push factors from their home country and encouragement on social media means that Chinese migrants will continue to seek routes to America.

And with both migration and the perceived threat from China likely to be features of the upcoming U.S. election, there is a risk that increased Chinese migration could become politicized, leaning further into existing tensions between Washington and Beijing.

Meredith Oyen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

congress pandemic deaths south america mexico china-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex