Government

Employment By Race: The Employment-to-Population Ratio For Blacks vs. Whites Has Changed

In the over 50 years that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has been keeping track, the share of Black Americans who are employed has consistently been…

In the over 50 years that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has been keeping track, the share of Black Americans who are employed has consistently been lower than the share of white Americans with paid jobs. This changed briefly for the first time ever in March of 2023. That month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded a greater percentage of Black Americans employed than white Americans. What explains this reversal and what, if anything, does it say about changes in access to employment by race?

The following article by Valerie Wilson and Aaron Sojourner has been edited ([ ]) and abridged (…) by Lorimer Wilson, Managing Editor of munKNEE.com – Your KEY To Making Money! – for the sake of clarity and brevity to provide a faster and easier read.

The Facts:

- The employment to population ratio (EPOP) is a core measure of labor market and economic strength. The measure expresses the share of a population employed instead of being not employed — which includes people searching for a job as well as many who are not, such as retirees, homemakers, and college students. In contrast, the unemployment rate looks only at those who are actively seeking work for pay and measures the share of people who have not found employment. The unemployment rate completely ignores retirees, homemakers, college students, and others who are not seeking paid work. Many economists consider the EPOP to be a more consistent or less ambiguous measure of labor market health than the unemployment rate.

- Since significant changes in the population occur infrequently, a higher EPOP is likely to reflect an actual increase in the level of employment. In contrast, a decline in the unemployment rate does not always signal an improvement in employment conditions as it can occur when people who have not found employment stop seeking work, even if there is not a significant increase in the level of employment. Americans under age 16 and those who are in the military or imprisoned are excluded from calculation of both the unemployment rate and the employment population ratio. Differences in employment population ratios by race can reflect many factors, such as differences in ages, geographies, health, employer discrimination, occupational segregation, prior convictions, and many other factors.

- In March 2023, Black Americans’ employment to population ratio exceeded that of white Americans for the first time in U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics records that started in 1972. This sparked speculation about whether this signaled a meaningful shift toward greater racial equity in the labor force. Subsequent data suggest that was something of a blip in the series — monthly labor market statistics for Black Americans are notoriously volatile – rather than a new normal in racial employment trends (see chart). However, Black and white EPOPs coming close enough to even tease the possibility that a higher percentage of the Black population was employed relative to whites is noteworthy. The difference in employment to population ratios between Black and white Americans has narrowed over time. In the last ten years (2014-2023), Black EPOP has averaged 3.1 percentage points lower than white EPOP. The average difference was twice that (6.5 percentage points) in prior decades (1972-2013).

- The convergence of Black and white EPOPs is partly the result of differences in the age demographics of the two populations. Since the Black population is younger than the white population, a larger share of the working age Black population is under age 50 when people are more likely to work. A larger share of the white population is older and more likely to have stopped working. This racial difference in population age demographics tends to raise Black EPOP and lower white EPOP. If you separate out different age groups, white EPOP is higher than Black EPOP at each age level, suggesting that the narrowing of the gap may not signal as large an increase in employment equity as the shrinkage of the raw EPOP gap might suggest, according to a recent analysis. If each age-by-race group’s employment rate is kept fixed at its observed level but the age distribution of Black Americans is shifted to match whites’ age distribution, then Black Americans would have an employment to population ratio about 8 percent lower than white Americans.

- However, the dramatic jobs recovery since the pandemic recession has been especially favorable to Black workers and this has contributed to the most recent narrowing in the employment to population ratios. The difference in employment to population ratios between Black and white Americans has averaged only 1 percentage point over the most recent 12 months. An important contributing factor is that the current economic recovery has been particularly beneficial to Black men. Black men have historically had a much lower employment to population ratio than white men, averaging 10.6 percentage points lower since 1972. What’s noteworthy about the current narrowing of the Black-white EPOP gap is that faster EPOP growth for Black men relative to white men has significantly narrowed the difference among men to an average of 4.5 percentage points in the last year and a half. (The Black-white EPOP difference among women is much smaller, and Black women’s EPOP often exceeds that of white women in tight labor markets.) While these gains represent positive improvements, they must also be weighed against the issue of undercounting of the Black population and the disproportionate share of incarcerated Black men who are excluded from the BLS survey data sample of the “civilian, non-institutionalized population.”

- So what, if anything, do these observations say about racial equity and the persistence of labor market discrimination? While Black workers made notable gains and narrowed differences in employment with white workers during the pandemic recovery, there is consistent and persistent evidence that Black job seekers encounter greater difficulties in being hired than white job seekers. The unemployment rate tells us about the difficulty finding employment among those in the labor force, including the employed and those actively seeking work. The unemployment rate for Black workers tends to be twice that of white workers and this is true throughout the business cycle, at nearly every level of education, across age cohorts and for women and men. In other words, Black workers are twice as likely as white workers to be stuck in job search mode rather than earning at any point in time. Black and white Americans differ in many ways besides race. However, the gap between unemployment rates is not much explained by differences in age, education, marital status, or state of residence. Experiments show that potential employers are less likely to call back Black applicants who have the same or better credentials as white applicants (see here and here).

- In addition to differences in hiring, the burden of job loss and unemployment also falls disproportionately on Black workers. A new crop of studies that follow workers over time reveal vast inequality in workers’ labor market experiences over their careers (see here and here). About 4 in 5 workers enjoy very stable employment over decades rarely getting laid off or being trapped in unemployment. In contrast, a small group suffers very unstable employment and suffers most of the economy’s unemployment, with 6 times higher job turnover rates and 10 times more months spent unemployed. White Americans disproportionately belong to the first group and Black Americans to the second (see here).

What this Means:

Tight labor markets are important because they tend to draw in more marginally attached workers. In tight labor markets when labor supply is limited, employers have less discretion to discriminate. Ensuring that the Fed takes its responsibility to ensure full employment seriously alongside its responsibility to ensure price and financial stability will go a long way to promoting the tight labor markets that pressure employers to equalize opportunities. Innovation and additional investment in enforcing American workers’ rights to freedom from employers’ racial discrimination could help equalize opportunity. During the first two years of the Biden administration, the federal government made large, long-term commitments to invest in American transportation and energy infrastructure and in our manufacturing sector through the bipartisan infrastructure bill, the CHIPS & Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act. These investments are expected to support nearly 3 million jobs annually over the next 10 years, according to White House estimates. This boom in demand for American workers especially benefits those with less formal education who had been losing ground in the economy for decades.

recession unemployment economic recovery fed white house recession recovery unemployment

Government

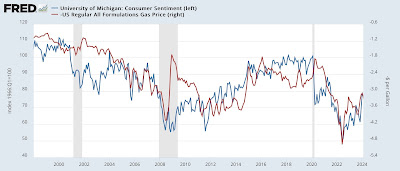

“Are you better off than you were four years ago?”

– by New Deal democratNo economic news today, so let me take a look at the supposed killer recent GOP meme that they claim is completely unanswerable:…

- by New Deal democrat

No economic news today, so let me take a look at the supposed killer recent GOP meme that they claim is completely unanswerable: “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?”

Spread & Containment

AI can help predict whether a patient will respond to specific tuberculosis treatments, paving way for personalized care

People have been battling tuberculosis for thousands of years, and drug-resistant strains are on the rise. Analyzing large datasets with AI can help humanity…

Tuberculosis is the world’s deadliest bacterial infection. It afflicted over 10 million people and took 1.3 million lives in 2022. These numbers are predicted to increase dramatically because of the spread of multidrug-resistant TB.

Why does one TB patient recover from the infection while another succumbs? And why does one drug work in one patient but not another, even if they have the same disease?

People have been battling TB for millennia. For example, researchers have found Egyptian mummies from 2400 BCE that show signs of TB. While TB infections occur worldwide, the countries with the highest number of multidrug-resistant TB cases are Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus and Russia.

Researchers predict that the ongoing war in Ukraine will result in an increase in multidrug-resistant TB cases because of health care disruptions. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic reduced access to TB diagnosis and treatment, reversing decades of progress worldwide.

Rapidly and holistically analyzing available medical data can help optimize treatments for each patient and reduce drug resistance. In our recently published research, my team and I describe a new AI tool we developed that uses worldwide patient data to guide more personalized and effective treatment of TB.

Predicting success or failure

My team and I wanted to identify what variables can predict how a patient responds to TB treatment. So we analyzed more than 200 types of clinical test results, medical imaging and drug prescriptions from over 5,000 TB patients in 10 countries. We examined demographic information such as age and gender, prior treatment history and whether patients had other conditions. Finally, we also analyzed data on various TB strains, such as what drugs the pathogen is resistant to and what genetic mutations the pathogen had.

Looking at enormous datasets like these can be overwhelming. Even most existing AI tools have had difficulty analyzing large datasets. Prior studies using AI have focused on a single data type – such as imaging or age alone – and had limited success predicting TB treatment outcomes.

We used an approach to AI that allowed us to analyze a large and diverse number of variables simultaneously and identify their relationship to TB outcomes. Our AI model was transparent, meaning we can see through its inner workings to identify the most meaningful clinical features. It was also multimodal, meaning it could interpret different types of data at the same time.

Once we trained our AI model on the dataset, we found that it could predict treatment prognosis with 83% accuracy on newer, unseen patient data and outperform existing AI models. In other words, we could feed a new patient’s information into the model and the AI would determine whether a specific type of treatment will either succeed or fail.

We observed that clinical features related to nutrition, particularly lower BMI, are associated with treatment failure. This supports the use of interventions to improve nourishment, as TB is typically more prevalent in undernourished populations.

We also found that certain drug combinations worked better in patients with certain types of drug-resistant infections but not others, leading to treatment failure. Combining drugs that are synergistic, meaning they enhance each other’s potency in the lab, could result in better outcomes. Given the complex environment in the body compared with conditions in the lab, it has so far been unclear whether synergistic relationships between drugs in the lab hold up in the clinic. Our results suggest that using AI to weed out antagonistic drugs, or drugs that inhibit or counteract each other, early in the drug discovery process can avoid treatment failures down the line.

Ending TB with the help of AI

Our findings may help researchers and clinicians meet the World Health Organization’s goal to end TB by 2035, by highlighting the relative importance of different types of clinical data. This can help prioritize public health efforts to mitigate TB.

While the performance of our AI tool is promising, it isn’t perfect in every case, and more training is needed before it can be used in the clinic. Demographic diversity can be high within a country and may even vary between hospitals. We are working to make this tool more generalizable across regions.

Our goal is to eventually tailor our AI model to identify drug regimens suitable for individuals with certain conditions. Instead of a one-size-fits-all treatment approach, we hope that studying multiple types of data can help physicians personalize treatments for each patient to provide the best outcomes.

Sriram Chandrasekaran receives funding from the US National Institutes of Health.

treatment genetic pandemic covid-19 spread russia ukraine world health organizationGovernment

QE By A Different Name Is Still QE

The Fed added Quantitative Easing (QE) to its monetary policy toolbox in 2008. At the time, the financial system was imploding. Fed Chair Ben Bernanke…

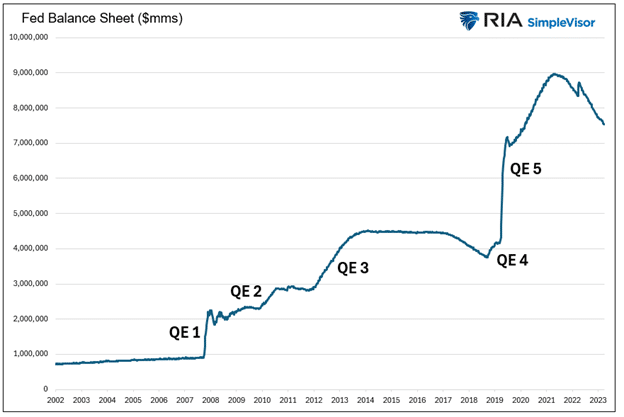

The Fed added Quantitative Easing (QE) to its monetary policy toolbox in 2008. At the time, the financial system was imploding. Fed Chair Ben Bernanke bought $1.5 trillion U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to staunch a financial disaster. The drastic action was sold to the public as a one-time, emergency operation to stabilize the banking system and economy. Since the initial round of QE, there have been four additional rounds, culminating with the mind-boggling $5 trillion operation in 2020 and 2021.

QE is no longer a tool for handling a crisis. It has morphed into a policy to ensure the government can fund itself. However, as we are learning today, QE has its faults. For example, it’s not an appropriate policy in times of high inflation like we have.

That doesn’t mean the Fed can’t provide liquidity to help the Treasury fund the government’s deficits. They just need to be more creative. To that end, rumors are floating around that a new variation of QE will help bridge potential liquidity shortfalls.

The Sad Fiscal Situation

The Federal government now pays over $1 trillion in interest expenses annually. Before they spend a dime on the military, social welfare, or the tens of thousands of other expenditures, one-third of the government’s tax revenue pays for the interest on the $34 trillion in debt, representing deficits of years and decades past.

There are many ways to address deficits and overwhelming debt, such as spending cuts or higher taxes. While logical approaches, politicians favor more debt. Let’s face it: winning an election on the promise of spending cuts and tax increases is hard. It’s even harder to keep your seat in Congress if you try to enact such changes.

More recently, the Federal Reserve has been forced to help fund today’s deficits and those of years past. We can debate the merits of such irresponsible behavior all day, but for investors, it’s much more critical to assess how the Fed and Treasury might keep the debt scheme going when QE is not an option.

Borrowing For Deficits

Before spreading rumors about a new variation of QE, let’s review the problem. The graph below shows the widening gap between federal spending and tax receipts. Literally, the gap between the two lines amounts to the cumulative Federal deficit. Instead of plotting deficit data, we prefer outstanding total federal debt as it better represents the cumulative onus of deficits.

The graph below shows the Treasury debt has grown annually for the last 57 years by about 1.5% more than the interest expense. Such may not seem like a lot, but 57 years of compounding makes a big difference.

Declining interest rates for the last 40+ years are to thank for the differential. The green line shows the effective interest rate has steadily dropped until recently. Even with the current instance of higher interest rates, the effective interest rate is only 3.00%.

Fiscal Dominance

The Fed has been increasingly pressed to help the U.S. Treasury maintain the ability to fund its debt at reasonable interest rates. In addition to presiding over lower-than-normal interest rates for the last 30 years, QE helps the cause. By removing Treasury and mortgage-backed securities from the market, the market can more easily absorb new Treasury issuance.

Fiscal dominance, as we are experiencing, occurs when monetary policy helps the Treasury fund its debts. Per The CATO Institute:

Fiscal dominance occurs when central banks use their monetary powers to support the prices of government securities and to peg interest rates at low levels to reduce the costs of servicing sovereign debt.

2019 Revisited

In 2019, before the massive pandemic-related deficits, government spending ramped up over the prior few years due to higher spending and tax cuts. In September 2019, the repo markets strained under the pressure of the growing Treasury demands. The banks had plenty of securities but no cash to lend. For more information on the incident and the importance of liquidity in maintaining financial stability, please read our article, Liquidity Problems.

When a bank, broker, or investor can’t borrow money despite being willing to post U.S. Treasury collateral, that is a clear sign that the banking system lacks liquidity. That is exactly what happened in 2019.

The Fed came to the rescue, offering QE and lowering interest rates.

Shortly later, in March 2020, government spending blossomed with the pandemic, and the Fed was quick to help. As we shared earlier, the Fed, via QE, removed over $5 trillion of assets from the financial markets. That amount was on par with the surge of government debt.

The Fed is mandated to manage policy to achieve maximum employment and stable prices. Mandated or not, recent experiences demonstrate the Fed has become the de facto lender to the Treasury, albeit indirectly.

The Fed Is In Handcuffs

While Jerome Powell and the Fed might like to help the government meet their exorbitant funding needs with lower interest rates and QE, they are shackled. Higher inflation resulting from the pandemic and fiscal and monetary policies force them to reduce their balance sheet and keep rates abnormally high.

Unfortunately, as we wrote in Liquidity Problems, the issuance of Treasury debt rapidly drains excess liquidity from the system.

While the Fed hesitates to cut rates or do QE, they may have another trick up their sleeve.

Spreading Rumors

The following is based on rumors from numerous sources about what the Fed and banking regulators may do to alleviate funding pressures and liquidity shortfalls.

Banks have regulatory limits on the amount of leverage they can employ. The amount is set by the type and riskiness of assets they hold. For instance, U.S. Treasuries can be leveraged more than a loan to small businesses. A dollar of a bank deposit may allow a bank to buy $5 of a Treasury note but only lend $3 to a riskier borrower.

The regulatory structure currently recognizes eight Global Systematically Important Banks (GSIB). They are as follows: Bank of America, The Bank of New York, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, State Street, and Wells Fargo & Company.

Rumor has it that the regulators could eliminate leverage requirements for the GSIBs. Doing so would infinitely expand their capacity to own Treasury securities. That may sound like a perfect solution, but there are two problems: the banks must be able to fund the Treasury assets and avoid losing money on them.

BTFP To The Rescue Again

A year ago, the Fed created the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) to bail out banks with underwater securities. The program allowed banks to pledge underwater Treasury assets to the Fed. In exchange, the Fed would loan them money equal to the bond’s par value, even though the bonds were trading at discounts to par.

Remember, since 2008, banks no longer have to book gains or losses on assets unless they are impaired or sold.

In a new scheme, bank regulators could eliminate the need for GSIBs to hold capital against Treasury securities while the Fed reenacts some version of BTFP. Under such a regime, the banks could buy Treasury notes and fund them via the BTFP. If the borrowing rate is less than the bond yield, they make money and, therefore, should be very willing to participate, as there is potentially no downside.

The Fed still uses its balance sheet in this scheme, but it could sell it to the public as a non-inflationary action, as it did in March 2023 when the BTFP was introduced.

Summary

The federal government’s escalating debt and interest expenses underscore the challenges posed by prolonged deficit spending. The problem has forced the Fed to help the Treasury meet its burgeoning needs. The situation becomes more evident with each passing day.

The recently closed BTFP program and rumors about leverage requirements provide insight into how the Fed might accomplish this tall task while maintaining its hawkish anti-inflationary policy stance.

The post QE By A Different Name Is Still QE appeared first on RIA.

treasury securities bonds repo markets pandemic monetary policy qe fed federal reserve government debt congress interest rates-

Spread & Containment1 week ago

Spread & Containment1 week agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex