International

Capitalism, Cartels, and Unintended Consequences

Donald Trump’s plan for a wall across the American southern border is one of the most controversial policy proposals in American history. Along with…

Donald Trump’s plan for a wall across the American southern border is one of the most controversial policy proposals in American history. Along with Trump’s usual dose of falsehoods and anti-immigration fear-mongering, the opioid crisis quickly became a favorite talking point to support his flagship policy, specifically the increase in deaths from fentanyl overdoses. Trump lauded the wall as a sure fire way to halt drugs from crossing over the border, even though “U.S. statistics, analysts and ongoing testimony at the New York City trial of drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman show that most hard drugs entering the U.S. from Mexico come through land border crossings staffed by agents, not open sections of the border.”

Of course, these are poor solutions, because they ignore the overdose crisis entirely, and simply rehash war on drugs rhetoric. The suggestion these policies make is that America needs to take its drug problem even more seriously, as severe drug possession and trafficking penalties are not enough. The “tough on drugs” policy over the last 60 years has failed to deliver America free from drug addiction, and has instead tied America’s drug crisis far beyond the southern border, to homelessness, destabilization of the family unit, income inequality, institutional distrust, worsening mental health, and the criminalization of poverty. But if the war on drugs isn’t the solution, then what is?

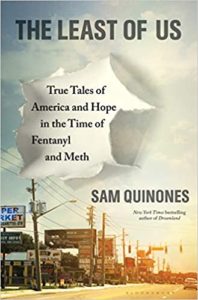

Why has the drug epidemic increased in scale even though the nation has made such progress in economic growth, education, and crime since the 1970’s? Is American capitalism to blame for the drug epidemic? Has America given up on the least of us? Sam Quinones joins EconTalk host Russ Roberts to discuss the link between drug addiction and homelessness, the economics of drug cartel monopolies, and the possible solutions to the opioid crisis.

An important theme Quinones stresses is the sheer scale of the drug crisis. He argues that this wave of the drug epidemic is distinct from the problem faced in the 1970’s with its proliferation of drugs, specifically fentanyl and meth. Further, the epidemic is affecting the entire nation, not just pockets of certain urban areas. The crisis has shifted to devastating suburban and rural areas, and has become so rampant that Quinones believes that the overdose death toll is significantly undercounted by at least 20-30%. The COVID-19 pandemic brought this problem even more into the spotlight, as homelessness, suicides, and deaths from despair skyrocketed.

One of the reasons overdose is so common is because of the rise of fentanyl. Quinones explains that fentanyl really only began to filter into American drug markets in the mid-2000’s, soon killing hundreds of thousands of people in a “big loop of a death curve.” So why is fentanyl so deadly? Mostly, unintended consequences. Roberts describes how fentanyl began as a fantastic drug for surgery, as it gets to the brain very quickly and also wears off very quickly. The rapid high of fentanyl also made it a miracle drug for cartels, and they quickly introduced it into other drugs. To Quinones, this innovation in the drug market was inevitable.

The war on drugs is also complicit in the incentivization of drug dealers. As elucidated by Benjamin Powell in an article for Econlib, the war was fought on the supply side, as it attempted to cut off the sales of drugs. However, all this did was further empower cartels through increased drug prices and monopolization, “Because the demand for drugs is not price-sensitive, each “victory” in the war on drugs enhances drug dealers’ revenue, making future decreases in supply all the harder to achieve. It is no accident that the number of annual drug-related deaths in Mexico almost quintupled from 2,300 in 2007 to 11,000 in 2010.”

Quinones and Roberts discuss this same topic in reference to the Mexican government’s crack down on methamphetamines. The Mexican government outlawed possession of the key ingredient in methamphetamine, ephedrine; however, the adaptability of methamphetamine producers allowed for virtually endless strains of the drug. Drug kingpins being killed by the Mexican government simply allowed for further consolidation of the market for the remaining cartels, causing drug prices to rise, and creating more of an incentive for cartels to increase production.

Why is America addicted? Quinones and Roberts concur that the drug epidemic is not a problem in itself, it’s more of a symptom to the true disease: people are lost. Quinones makes this point by laying the blame on American capitalism, as to him, “Corporations behave like traffickers and traffickers behave like corporations.”

To Quinones, monopolization through corporatization has created addiction through destitution. Americans put out business by large multinational corporations have almost nowhere else to turn but to sell drugs to get by financially and use drugs to cope with the loss of their life’s work. Walmart’s success is just one example of America choosing prices over people, as small businesses on main street are far more important than just jobs, as they provide a source of community and social cohesion. In Quinones’ view, monopoly is inevitable.

Roberts disagrees with the indictment of capitalism. He emphasizes two areas of social life where Americans have typically found meaning and community: family and religion. Roberts believes that the decline in religious belief and the growing presence of divorce and people choosing not to get married is the true culprit of American drug addiction.

The theme of social isolation and dissolution is a common one among EconTalk episodes, as this episode “forms something of a trilogy with recent episodes with Johann Hari on Lost Connections, and Noreena Hertz on The Lonely Century,”

Quinones ends up ardently agreeing with Roberts in this segment of the argument. Both think that the erosion of family and religious institutions has left few social institutions to care for “the least of us.” This is the reason he titled his book The Least of Us. The dissolution of community has produced apathy towards social problems, and an implicit refusal to solve them.

Roberts is intrigued by this, and defends capitalism by saying the system itself is morally neutral, and is very good at giving people what they want, so the true question to him is why do so many people seem to want a life of opioid addiction?

S what are the solutions? To Quinones, focusing on the least of us is necessary. Each individual has a role to play in curing an addicted America

And, what must our response be then? Well again, the book’s title, The Least of Us, seems to me to be the appropriate one, where we return to local–focus on our neighbors, focus on our streets, focus on our churches, synagogues, mosques, what have you. Focus on our local business, patronize our local business. Get outside, for God’s sake.

…we need to understand the power of walking down Main Street and seeing the guy who fixed your shoes, you know, a year ago, and say, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ Be a part of a community.

Quinones’ last point is one of hope. Quinones and Roberts end with agreement that incremental steps to rebuild one’s community is the best place to start.

I had some questions [below] while listening to this episode. We hope you’ll share your thoughts with us as well!

1- The relationship Quinones is discussing between addiction and homelessness is interesting. Does addiction cause homelessness, as Quinones believes, or does homelessness cause the addiction problem? How do factors such as high housing costs, disabilities, the failed war on drugs creating institutional poverty, and systemic racism affect homelessness? How would policies such as drug decriminalization and rehabilitation combined with transitional housing for the homeless impact the link between homelessness and addiction?

2- A theme throughout the episode is unintended consequences. How can unintended consequences from morally neutral things be avoided? Legality doesn’t seem to be the answer, so how can civil society and the marketplace solve its own problems? How can the destruction in creative destruction be minimized?

3- Healthcare policy has a definite role to play in this discussion. How have policies such as certificate of need laws and restrictive scope of practice laws affected the ability of drug users to receive care? How would expansions to the social safety net such as with a public option healthcare system fare in alleviating the opioid crisis?

4- Quinones states that the cartels producing the fentanyl don’t care how deadly it is because of their position up the supply chain, they’re disconnected from the harm that a customer’s death from an overdose would cause to an individual seller, and this is why fentanyl continues to kill people. Why would the individual sellers themselves continue to sell such a deadly drug with a margin of error so low?

5- The thread of discussion mentioned in the above question led to Roberts’ question of why customers would ever willingly purchase a stronger version of meth that has far worse side effects, such as paranoia and a larger chance of overdose. In his words, “Why would anyone take this stuff? It turns you into this paranoid person who can’t hold a job. Now, I understand, once you’re addicted, you’re in trouble. But, how do you move from that to that world?” How does Quinones answer this question, and to what extent do you agree with his explanation?

(0 COMMENTS) depression pandemic covid-19 economic growth link trump deaths mexicoInternational

Riley Gaines Explains How Women’s Sports Are Rigged To Promote The Trans Agenda

Riley Gaines Explains How Women’s Sports Are Rigged To Promote The Trans Agenda

Is there a light forming when it comes to the long, dark and…

Is there a light forming when it comes to the long, dark and bewildering tunnel of social justice cultism? Global events have been so frenetic that many people might not remember, but only a couple years ago Big Tech companies and numerous governments were openly aligned in favor of mass censorship. Not just to prevent the public from investigating the facts surrounding the pandemic farce, but to silence anyone questioning the validity of woke concepts like trans ideology.

From 2020-2022 was the closest the west has come in a long time to a complete erasure of freedom of speech. Even today there are still countries and Europe and places like Canada or Australia that are charging forward with draconian speech laws. The phrase "radical speech" is starting to circulate within pro-censorship circles in reference to any platform where people are allowed to talk critically. What is radical speech? Basically, it's any discussion that runs contrary to the beliefs of the political left.

Open hatred of moderate or conservative ideals is perfectly acceptable, but don't ever shine a negative light on woke activism, or you might be a terrorist.

Riley Gaines has experienced this double standard first hand. She was even assaulted and taken hostage at an event in 2023 at San Francisco State University when leftists protester tried to trap her in a room and demanded she "pay them to let her go." Campus police allegedly witnessed the incident but charges were never filed and surveillance footage from the college was never released.

It's probably the last thing a champion female swimmer ever expects, but her head-on collision with the trans movement and the institutional conspiracy to push it on the public forced her to become a counter-culture voice of reason rather than just an athlete.

For years the independent media argued that no matter how much we expose the insanity of men posing as women to compete and dominate women's sports, nothing will really change until the real female athletes speak up and fight back. Riley Gaines and those like her represent that necessary rebellion and a desperately needed return to common sense and reason.

In a recent interview on the Joe Rogan Podcast, Gaines related some interesting information on the inner workings of the NCAA and the subversive schemes surrounding trans athletes. Not only were women participants essentially strong-armed by colleges and officials into quietly going along with the program, there was also a concerted propaganda effort. Competition ceremonies were rigged as vehicles for promoting trans athletes over everyone else.

The bottom line? The competitions didn't matter. The real women and their achievements didn't matter. The only thing that mattered to officials were the photo ops; dudes pretending to be chicks posing with awards for the gushing corporate media. The agenda took precedence.

Lia Thomas, formerly known as William Thomas, was more than an activist invading female sports, he was also apparently a science project fostered and protected by the athletic establishment. It's important to understand that the political left does not care about female athletes. They do not care about women's sports. They don't care about the integrity of the environments they co-opt. Their only goal is to identify viable platforms with social impact and take control of them. Women's sports are seen as a vehicle for public indoctrination, nothing more.

The reasons why they covet women's sports are varied, but a primary motive is the desire to assert the fallacy that men and women are "the same" psychologically as well as physically. They want the deconstruction of biological sex and identity as nothing more than "social constructs" subject to personal preference. If they can destroy what it means to be a man or a woman, they can destroy the very foundations of relationships, families and even procreation.

For now it seems as though the trans agenda is hitting a wall with much of the public aware of it and less afraid to criticize it. Social media companies might be able to silence some people, but they can't silence everyone. However, there is still a significant threat as the movement continues to target children through the public education system and women's sports are not out of the woods yet.

The ultimate solution is for women athletes around the world to organize and widely refuse to participate in any competitions in which biological men are allowed. The only way to save women's sports is for women to be willing to end them, at least until institutions that put doctrine ahead of logic are made irrelevant.

Government

Congress’ failure so far to deliver on promise of tens of billions in new research spending threatens America’s long-term economic competitiveness

A deal that avoided a shutdown also slashed spending for the National Science Foundation, putting it billions below a congressional target intended to…

Federal spending on fundamental scientific research is pivotal to America’s long-term economic competitiveness and growth. But less than two years after agreeing the U.S. needed to invest tens of billions of dollars more in basic research than it had been, Congress is already seriously scaling back its plans.

A package of funding bills recently passed by Congress and signed by President Joe Biden on March 9, 2024, cuts the current fiscal year budget for the National Science Foundation, America’s premier basic science research agency, by over 8% relative to last year. That puts the NSF’s current allocation US$6.6 billion below targets Congress set in 2022.

And the president’s budget blueprint for the next fiscal year, released on March 11, doesn’t look much better. Even assuming his request for the NSF is fully funded, it would still, based on my calculations, leave the agency a total of $15 billion behind the plan Congress laid out to help the U.S. keep up with countries such as China that are rapidly increasing their science budgets.

I am a sociologist who studies how research universities contribute to the public good. I’m also the executive director of the Institute for Research on Innovation and Science, a national university consortium whose members share data that helps us understand, explain and work to amplify those benefits.

Our data shows how underfunding basic research, especially in high-priority areas, poses a real threat to the United States’ role as a leader in critical technology areas, forestalls innovation and makes it harder to recruit the skilled workers that high-tech companies need to succeed.

A promised investment

Less than two years ago, in August 2022, university researchers like me had reason to celebrate.

Congress had just passed the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act. The science part of the law promised one of the biggest federal investments in the National Science Foundation in its 74-year history.

The CHIPS act authorized US$81 billion for the agency, promised to double its budget by 2027 and directed it to “address societal, national, and geostrategic challenges for the benefit of all Americans” by investing in research.

But there was one very big snag. The money still has to be appropriated by Congress every year. Lawmakers haven’t been good at doing that recently. As lawmakers struggle to keep the lights on, fundamental research is quickly becoming a casualty of political dysfunction.

Research’s critical impact

That’s bad because fundamental research matters in more ways than you might expect.

For instance, the basic discoveries that made the COVID-19 vaccine possible stretch back to the early 1960s. Such research investments contribute to the health, wealth and well-being of society, support jobs and regional economies and are vital to the U.S. economy and national security.

Lagging research investment will hurt U.S. leadership in critical technologies such as artificial intelligence, advanced communications, clean energy and biotechnology. Less support means less new research work gets done, fewer new researchers are trained and important new discoveries are made elsewhere.

But disrupting federal research funding also directly affects people’s jobs, lives and the economy.

Businesses nationwide thrive by selling the goods and services – everything from pipettes and biological specimens to notebooks and plane tickets – that are necessary for research. Those vendors include high-tech startups, manufacturers, contractors and even Main Street businesses like your local hardware store. They employ your neighbors and friends and contribute to the economic health of your hometown and the nation.

Nearly a third of the $10 billion in federal research funds that 26 of the universities in our consortium used in 2022 directly supported U.S. employers, including:

A Detroit welding shop that sells gases many labs use in experiments funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Department of Defense and Department of Energy.

A Dallas-based construction company that is building an advanced vaccine and drug development facility paid for by the Department of Health and Human Services.

More than a dozen Utah businesses, including surveyors, engineers and construction and trucking companies, working on a Department of Energy project to develop breakthroughs in geothermal energy.

When Congress shortchanges basic research, it also damages businesses like these and people you might not usually associate with academic science and engineering. Construction and manufacturing companies earn more than $2 billion each year from federally funded research done by our consortium’s members.

Jobs and innovation

Disrupting or decreasing research funding also slows the flow of STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – talent from universities to American businesses. Highly trained people are essential to corporate innovation and to U.S. leadership in key fields, such as AI, where companies depend on hiring to secure research expertise.

In 2022, federal research grants paid wages for about 122,500 people at universities that shared data with my institute. More than half of them were students or trainees. Our data shows that they go on to many types of jobs but are particularly important for leading tech companies such as Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Intel.

That same data lets me estimate that over 300,000 people who worked at U.S. universities in 2022 were paid by federal research funds. Threats to federal research investments put academic jobs at risk. They also hurt private sector innovation because even the most successful companies need to hire people with expert research skills. Most people learn those skills by working on university research projects, and most of those projects are federally funded.

High stakes

If Congress doesn’t move to fund fundamental science research to meet CHIPS and Science Act targets – and make up for the $11.6 billion it’s already behind schedule – the long-term consequences for American competitiveness could be serious.

Over time, companies would see fewer skilled job candidates, and academic and corporate researchers would produce fewer discoveries. Fewer high-tech startups would mean slower economic growth. America would become less competitive in the age of AI. This would turn one of the fears that led lawmakers to pass the CHIPS and Science Act into a reality.

Ultimately, it’s up to lawmakers to decide whether to fulfill their promise to invest more in the research that supports jobs across the economy and in American innovation, competitiveness and economic growth. So far, that promise is looking pretty fragile.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 16, 2024.

Jason Owen-Smith receives research support from the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Wellcome Leap.

economic growth covid-19 grants congress vaccine chinaInternational

What’s Driving Industrial Development in the Southwest U.S.

The post-COVID-19 pandemic pipeline, supply imbalances, investment and construction challenges: these are just a few of the topics address by a powerhouse…

The post-COVID-19 pandemic pipeline, supply imbalances, investment and construction challenges: these are just a few of the topics address by a powerhouse panel of executives in industrial real estate this week at NAIOP’s I.CON West in Long Beach, California. Led by Dawn McCombs, principal and Denver lead industrial specialist for Avison Young, the panel tackled some of the biggest issues facing the sector in the Western U.S.

Starting with the pandemic in 2020 and continuing through 2022, McCombs said, the industrial sector experienced a huge surge in demand, resulting in historic vacancies, rent growth and record deliveries. Operating fundamentals began to normalize in 2023 and construction starts declined, certainly impacting vacancy and absorption moving forward.

“Development starts dropped by 65% year-over-year across the U.S. last year. In Q4, we were down 25% from pre-COVID norms,” began Megan Creecy-Herman, president, U.S. West Region, Prologis, noting that all of that is setting us up to see an improvement of fundamentals in the market. “U.S. vacancy ended 2023 at about 5%, which is very healthy.”

Vacancies are expected to grow in Q1 and Q2, peaking mid-year at around 7%. Creecy-Herman expects to see an increase in absorption as customers begin to have confidence in the economy, and everyone gets some certainty on what the Fed does with interest rates.

“It’s an interesting dynamic to see such a great increase in rents, which have almost doubled in some markets,” said Reon Roski, CEO, Majestic Realty Co. “It’s healthy to see a slowing down… before [rents] go back up.”

Pre-pandemic, a lot of markets were used to 4-5% vacancy, said Brooke Birtcher Gustafson, fifth-generation president of Birtcher Development. “Everyone was a little tepid about where things are headed with a mediocre outlook for 2024, but much of this is normalizing in the Southwest markets.”

McCombs asked the panel where their companies found themselves in the construction pipeline when the Fed raised rates in 2022.

In Salt Lake City, said Angela Eldredge, chief operations officer at Price Real Estate, there is a typical 12-18-month lead time on construction materials. “As rates started to rise in 2022, lots of permits had already been pulled and construction starts were beginning, so those project deliveries were in fall 2023. [The slowdown] was good for our market because it kept rates high, vacancies lower and helped normalize the market to a healthy pace.”

A supply imbalance can stress any market, and Gustafson joked that the current imbalance reminded her of a favorite quote from the movie Super Troopers: “Desperation is a stinky cologne.” “We’re all still a little crazed where this imbalance has put us, but for the patient investor and owner, there will be a rebalancing and opportunity for the good quality real estate to pass the sniff test,” she said.

At Bircher, Gustafson said that mid-pandemic, there were predictions that one billion square feet of new product would be required to meet tenant demand, e-commerce growth and safety stock. That transition opened a great opportunity for investors to run at the goal. “In California, the entitlement process is lengthy, around 24-36 months to get from the start of an acquisition to the completion of a building,” she said. Fast forward to 2023-2024, a lot of what is being delivered in 2024 is the result of that chase.

“Being an optimistic developer, there is good news. The supply imbalance helped normalize what was an unsustainable surge in rents and land values,” she said. “It allowed corporate heads of real estate to proactively evaluate growth opportunities, opened the door for contrarian investors to land bank as values drop, and provided tenants with options as there is more product. Investment goals and strategies have shifted, and that’s created opportunity for buyers.”

“Developers only know how to run and develop as much as we can,” said Roski. “There are certain times in cycles that we are forced to slow down, which is a good thing. In the last few years, Majestic has delivered 12-14 million square feet, and this year we are developing 6-8 million square feet. It’s all part of the cycle.”

Creecy-Herman noted that compared to the other asset classes and opportunities out there, including office and multifamily, industrial remains much more attractive for investment. “That was absolutely one of the things that underpinned the amount of investment we saw in a relatively short time period,” she said.

Market rent growth across Los Angeles, Inland Empire and Orange County moved up more than 100% in a 24-month period. That created opportunities for landlords to flexible as they’re filling up their buildings. “Normalizing can be uncomfortable especially after that kind of historic high, but at the same time it’s setting us up for strong years ahead,” she said.

Issues that owners and landlords are facing with not as much movement in the market is driving a change in strategy, noted Gustafson. “Comps are all over the place,” she said. “You have to dive deep into every single deal that is done to understand it and how investment strategies are changing.”

Tenants experienced a variety of challenges in the pandemic years, from supply chain to labor shortages on the negative side, to increased demand for products on the positive, McCombs noted.

“Prologis has about 6,700 customers around the world, from small to large, and the universal lesson [from the pandemic] is taking a more conservative posture on inventories,” Creecy-Herman said. “Customers are beefing up inventories, and that conservatism in the supply chain is a lesson learned that’s going to stick with us for a long time.” She noted that the company has plenty of clients who want to take more space but are waiting on more certainty from the broader economy.

“E-commerce grew by 8% last year, and we think that’s going to accelerate to 10% this year. This is still less than 25% of all retail sales, so the acceleration we’re going to see in e-commerce… is going to drive the business forward for a long time,” she said.

Roski noted that customers continually re-evaluate their warehouse locations, expanding during the pandemic and now consolidating but staying within one delivery day of vast consumer bases.

“This is a generational change,” said Creecy-Herman. “Millions of young consumers have one-day delivery as a baseline for their shopping experience. Think of what this means for our business long term to help our customers meet these expectations.”

McCombs asked the panelists what kind of leasing activity they are experiencing as a return to normalcy is expected in 2024.

“During the pandemic, shifts in the ports and supply chain created a build up along the Mexican border,” said Roski, noting border towns’ importance to increased manufacturing in Mexico. A shift of populations out of California and into Arizona, Nevada, Texas and Florida have resulted in an expansion of warehouses in those markets.

Eldridge said that Salt Lake City’s “sweet spot” is 100-200 million square feet, noting that the market is best described as a mid-box distribution hub that is close to California and Midwest markets. “Our location opens up the entire U.S. to our market, and it’s continuing to grow,” she said.

The recent supply chain and West Coast port clogs prompted significant investment in nearshoring and port improvements. “Ports are always changing,” said Roski, listing a looming strike at East Coast ports, challenges with pirates in the Suez Canal, and water issues in the Panama Canal. “Companies used to fix on one port and that’s where they’d bring in their imports, but now see they need to be [bring product] in a couple of places.”

“Laredo, [Texas,] is one of the largest ports in the U.S., and there’s no water. It’s trucks coming across the border. Companies have learned to be nimble and not focused on one area,” she said.

“All of the markets in the southwest are becoming more interconnected and interdependent than they were previously,” Creecy-Herman said. “In Southern California, there are 10 markets within 500 miles with over 25 million consumers who spend, on average, 10% more than typical U.S. consumers.” Combined with the port complex, those fundamentals aren’t changing. Creecy-Herman noted that it’s less of a California exodus than it is a complementary strategy where customers are taking space in other markets as they grow. In the last 10 years, she noted there has been significant maturation of markets such as Las Vegas and Phoenix. As they’ve become more diversified, customers want to have a presence there.

In the last decade, Gustafson said, the consumer base has shifted. Tenants continue to change strategies to adapt, such as hub-and-spoke approaches. From an investment perspective, she said that strategies change weekly in response to market dynamics that are unprecedented.

McCombs said that construction challenges and utility constraints have been compounded by increased demand for water and power.

“Those are big issues from the beginning when we’re deciding on whether to buy the dirt, and another decision during construction,” Roski said. “In some markets, we order transformers more than a year before they are needed. Otherwise, the time comes [to use them] and we can’t get them. It’s a new dynamic of how leases are structured because it’s something that’s out of our control.” She noted that it’s becoming a bigger issue with electrification of cars, trucks and real estate, and the U.S. power grid is not prepared to handle it.

Salt Lake City’s land constraints play a role in site selection, said Eldridge. “Land values of areas near water are skyrocketing.”

The panelists agreed that a favorable outlook is ahead for 2024, and today’s rebalancing will drive a healthy industry in the future as demand and rates return to normalized levels, creating opportunities for investors, developers and tenants.

This post is brought to you by JLL, the social media and conference blog sponsor of NAIOP’s I.CON West 2024. Learn more about JLL at www.us.jll.com or www.jll.ca.

fed pandemic covid-19 real estate interest rates mexico-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International5 days ago

International5 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International5 days ago

International5 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges