Marginal revolution links to a great read on contemporary macroeconomics from J.W. Mason. It's mostly wrong, I think, but very thoughtfully puts together the wrong ideas behind contemporary policy macroeconomics.

Briefly, debt doesn't matter and there are no effective supply constraints. Borrow, spend without limit is the key to prosperity.

The fact that the Biden administration not only managed to push through an increase in public spending of close to 10 percent of GDP, but did so without any promises of longer-term deficit reduction, suggests a fundamental shift.

The fact that people like Lawrence Summers have been ignored in favor of progressives like Heather Boushey and Jared Bernstein, and deficit hawks like the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget have been left screeching irrelevantly from the sidelines, isn’t just gratifying as spectacle. It suggests a big move in the center of gravity of economic policy debates.

It really does seem that on the big macroeconomic questions, our side is winning.

I have noticed the same thing. Few Republicans mention the idea that today's spending has to be paid by tomorrow's taxes, and consequently today's stimulus must be repaid by tomorrow's prosperity. His "side" won. Until the well runs dry. (I also resist the assertion that economics must have political "sides," rather than an objective truth.)

But my interest in this particular post is to think about what it says about how thinking about economic policy is shifting, and how those shifts might be projected back onto economic theory.

The post is brilliant for systematizing the emerging view of economics in the Biden Administration, in much of the Fed, and its academic allies.

The conventional view

Mason is captures refreshingly well the other "side," conventional macroeconomic wisdom that emerged after the debacle of the 1970s:

Over the past generation, macroeconomic policy discussions have been based on a kind of textbook catechism that goes something like this: Over the long run, potential GDP grows at a rate based on supply-side factors — demographics, technological growth, and whatever institutions we think influence investment and labor force participation. Over the short run, there are random events that can cause actual spending to deviate from potential, which will be reflected in a higher or lower rate of inflation. [and also temporarily higher or lower output] These fluctuations are more or less symmetrical, both in frequency and in cost. The job of the central bank is to adjust interest rates to minimize the size of these deviations.

That's an excellent description of post 1970s, Lucas, Prescott, Sargent, Friedman macroeconomics. Unlike some other commenters from the "left," one cannot accuse him of ignorance. "Catechism" is a deliberate insult, as the view came from substantial theory and evidence, but let's leave that alone.

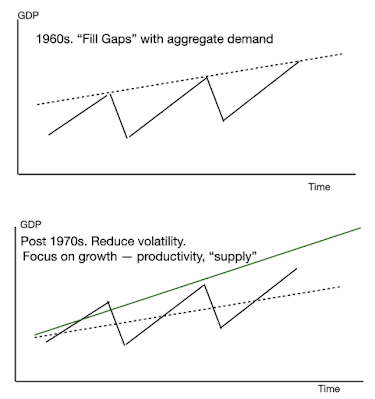

Here's a graphical version.

In the 1960s, macroeconomists thought that recessions were just "shortfalls" of "aggregate demand." The point of policy was to fill the valleys with aggregate demand, as indicated by the dashed line of the top graph. In the conventional reading, they tried it in the 1970s, and got inflation. They discovered that economies can run too hot as well. Thus, the objective shifted, as in the bottom graph. Now the job is to stabilize output, if not in the middle, at least below the top.

As one way of thinking about it, the dashed lines represent "supply." That's a bad word, as it is really the combined supply and demand of an economy working normally. How can an economy run "too hot?" Well, if your boss asked you to work 7 days a week 12 hours a day with no vacations to finish a special project, you could. But you would not want to do that forever. The economy as a whole can similarly push above what is long-run sustainable for a little while.

But at the same time, economists realized that the growth rate of "supply" is not a given, but instead heavily influenced by policy. So we should put more attention into the incentives for long-run growth, which all comes form the "supply" side -- capital, technology, productivity, efficiency.

Mason continues on the standard "catechism"

at any given moment, there’s a minimum level of unemployment consistent with price stability.

Milton Friedman, 1968. And that level is not zero. Try to push it too low, and you get inflation.

Smoothing out these fluctuations has real short run benefits, but no effects on long-term growth.

I.e. the best "demand" policy can do is the black dashed line in my lower graph.

large fiscal deficits may be very costly. Finally, while it may be necessary to stabilize overall spending in the economy, this should be done in a way that minimizes “distortions” of the pattern of economic activity and, in particular, does not reduce the incentive to work.

Correct again. To us, that pesky growth comes from incentives and lack of distortions.

The new view

But that's all over.

Policy debates — though not textbooks — have been moving away from this catechism for a while. Jason Furman’s New View of Fiscal Policy is an example I often point to; you can also see it in many statements from Powell and other Fed officials, as I’ve discussed here and here. But these are, obviously, just statements. The size and design of ARPA is a more consequential rejection of this catechism. Without being described as such, it’s a decisive recognition of half a dozen points that those of us on the left side of the macroeconomic debate have been making for years.

So, let's see the left side.

The balance of macroeconomic risks is not symmetrical. We don’t live in an economy that fluctuates around a long-term growth path, but one that periodically falls into recessions or depressions

.. demand shortfalls are much more frequent, persistent and damaging than is overheating. And to the extent the latter is a problem, it is much easier to interrupt the flow of spending than to restart it.

This is my graph of filling the valleys. It's not new economics, it's back to 1960s economics.

But that's just the beginning. The real paradigm shift, or flight of fancy depending on your "side," is on debt and supply:

3. The existence of hysteresis is one important reason that demand shortfalls are much more costly than overshooting. Overheating may have short-term costs in higher inflation, inflated asset prices and a redistribution of income toward relatively scarce factors (e.g. urban land), but it also is associated with a long-term increase in productive capacity — one that may eventually close the inflationary gap on its own.

This assertion will surprise survivors of the 1970s, when overheating manifestly did not lead to greater productive capacity, and the inflationary gap did not close on its own.

Shortfalls on the other hand lead to a reduction in potential output, and so may become self-perpetuating as potential GDP declines. Hysteresis also means that we cannot count on the economy returning to its long-term trend on its own — big falls in demand may persist indefinitely unless they are offset by some large exogenous boost to demand. Which in turn means that standard estimates of potential output understate the capacity of output to respond to higher spending.

Now here we have something genuinely new. Demand creates its own supply. (It's a shame Larry Summers is denigrated at the start, as he was early to the game on hysteresis and secular stagnation. For recent evidence against "hysteresis," see The Absence of Hysteresis in U.S. Macroeconomic Data by Luca Benati and Thomas A. Lubik.)

5. Public debt doesn’t matter. Maybe I missed it, but as far as I can tell, in the push for the Rescue Plan neither the administration nor the Congressional leadership made even a gesture toward deficit reduction, not even a pro forma comment that it might be desirable in principle or in the indefinite long run. The word “deficit” does not seem to have occurred in any official statement from the president since early February — and even then it was in the form of “it’s a mistake to worry about the deficit.”

I concur with that impression about current policy thinking, though not with its validity for this planet.

6. Work incentives don’t matter. For decades, welfare measures in the US have been carefully tailored to ensure that they did not broaden people’s choices other than wage labor.

This is lovely for its clear statement, and repudiation of 250 years of economics. The "stimulus" bill is full of additional work disincentives. Earn a dollar, lose a dollar's worth of benefits. And more are coming.

9. Weak demand is an ongoing problem, not just a short-term one.

This is 1939 "secular stagnation," Keynesian economics before growth economics came along in the 1950s. Just why weak demand is permanent remains a mystery. Prices and wages are not permanently sticky. 1940s Keynesianism thought so, but was pretty clearly not about a "long run."

If the child tax credit will cut child poverty by half, why would you want to do that for only one year? If a substantial part of the Rescue Plan should on the merits be permanent, that implies a permanently larger flow of public spending. The case needs to be made for this.

This is a good and logical point. If you take it seriously, though, it should show the illogic of the whole edifice. I found this claim that the child tax credit will cut child poverty in half illuminatingly ludicrous, not enticing. Really, that's all it takes? Why not spend $4 billlion and eliminate child poverty forever? Why not spend $8 billion and eliminate adult poverty? It hilarious that after the "war on poverty" declared in 1965, people could actually say with a straight face that the only reason "child poverty" remains in America is that we didn't pass a little tax credit.

It gets better:

What would a macroeconomics look like that assumed that the economy was normally well short of supply constraints rather than at potential on average, or was agnostic about whether there was a meaningful level of potential output at all?

My emphasis. Spend and goods will come. Don't worry about who makes it and why. Is there no constraint at all, as the MMTers seem to think? Yes, but it slips a derivative:

One idea that I find appealing is to think of supply as constraining the rate of growth of output, rather than its level... A better story, it seems to me, is that there is a ceiling on the rate that employment can grow — say 1.5 or 2 percent a year — without any special adjustment process

More broadly, thinking of supply constraints in terms of growth rates rather than levels would let us stop thinking about the supply side in terms of an abstract non monetary economy “endowed” with certain productive resources, and start thinking about it in terms of the coordination capabilities of markets. I feel sure this is the right direction to go. But a proper model needs to be worked out before it is ready for the textbooks.

It sure does need a new model! The standard textbook model starts with potential output = technology x function of capital and labor, y = Af(k,l). There is only so much the economy can produce, and once everyone who wants to work is working, the only way to improve is better technology or more efficiency, A. Mason is basically repudiating this fact. y = infinity, "there is always slack" in Stephanie Kelton's words, but dy/dt is limited by "frictions." (The first paragraph was about increasing L, but the second goes far beyond."

Labor rather than technology is at the heart of the vision -- as if we all got insanely richer than our ancestors by working more, not (as in fact) less.

The textbook model of labor markets that we still teach justifies a focus on “flexibility”, where real wages are determined by on productivity and a stronger position for labor can only lead to higher inflation or unemployment. Instead, we need a model where the relative position of labor affects real as well as nominal wages, and in which faster wage growth can be absorbed by faster productivity growth or a higher wage share as plausibly as by higher prices.

Productivity does not come from hard-won technical progress, corporate efficiency, the relentless pressure of competition. If you force companies to pay more, they will find whatever higher productivity it takes to generate the money to make that payment. Wow, millennia of misery could have been so easily avoided.

,how do we think about public debt and deficits once we abandon the idea that a constant debt-GDP ratio is a hard constraint? One possibility is that we think the deficit matters, but debt does not, just as we now think think that the rate of inflation matters but the absolute price level does not.

Mason recognizes the fact -- policy has moved here, and economics mops up to defend political choices. That's what's brilliant about this post

In short, just as a generation of mainstream macroeconomic theory was retconned into an after-the-fact argument for an inflation-targeting central bank,

This is not accurate, as calls for inflation targeting were there decades before it happened, but it's a nice metaphor

what we need now is textbooks and theories that bring out, systematize and generalize the reasoning that justifies a great expansion of public spending, unconstrained by conventional estimates of potential output, public debt or the need to preserve labor-market incentives.

My emphasis.

For the past generation, macroeconomic theory has been largely an abstracted parable of the 1970s, when high interest rates (supposedly) saved us from inflation. With luck, perhaps the next generation will learn macroeconomics as a parable of our own time, when big deficits saved us from secular stagnation and the coronavirus.

I would be very curious to hear what the alternative parable of the 1970s and 1980s is!

I was surprised to find one element of complete agreement. Mason may just be unaware how far contemporary labor economics has advanced from the policy world's fixation on the unemployment rate -- people without jobs who are looking for jobs.

1. The official unemployment rate is an unreliable guide to the true degree of labor market slack, all the time and especially in downturns. Most of the movement into and out of employment is from people who are not officially counted as unemployed. To assess labor market slack, we should also look at the employment-population ratio,

...there is not a well defined labor force, but a smooth gradient of proximity to employment. The short-term unemployed are the closest, followed by the longer-term unemployed, employed people seeking additional work, discouraged workers, workers disfavored by employers due to ethnicity, credentials, etc.

Beyond this are people whose claim on the social product is not normally exercised by paid labor – retired people, the disabled, full-time caregivers – but might come to be if labor market conditions were sufficiently favorable.

...Those who are most disadvantaged in the labor market, are the ones who benefit most from very low unemployment. The World War II experience, and the subsequent evolution of the racial wage gap, suggests that historically, sustained tight labor markets have been the most powerful force for closing the gap between black and white wages.

This is actually a good description of contemporary .. what do we call ourselves? Neoclassical? Neoliberal? Market? Incentive? ... economics. Labor economics has been focusing on the employment-population ratio for years. Ed Lazear harped on its decline. Casey Mulligan's book "redistribution recession" excoriated Obama policies precisely on labor force decline. Most labor economics focuses on employment. Labor economists largely pay little attention to the unemployment rate, calling it "job search."

There is indeed nothing like a booming, competitive labor market to help the disadvantaged. I thought this was a neoclassical point, made proudly by the Trump CEA!

But you see a gaping hole of logic.

6. Work incentives don’t matter. For decades, welfare measures in the US have been carefully tailored to ensure that they did not broaden people’s choices other than wage labor.

Well, if so much employment is on an active margin, people choosing employment or not, what other than incentives gets people to choose work? Work is not fun, especially jobs that the disadvantaged can aspire to. Since you must eat somehow, all the margins Mason mentions are exactly the margin between work and social program. So this (correct in my view) analysis of the labor market, with a large number of people on the margin of work or not, and a large number of employers who need a booming market to employ less skilled workers, flies completely in the face of "incentives don't matter." No, incentives are everything, precisely because of Mason's own well articulated view of labor force participation as the central margin.

The key problem of benefits is the disincentive posed by means testing -- earn more money, lose the benefits. A paragraph starts

8. Means testing is costly and imprecise.

and then wanders off without point. I think the point is, we should not means test at all. That sure cures the disincentives, but you had darn well better believe that debt doesn't matter!

All in all, this is a post worth reading carefully. This is indeed where we are going, and this is a nice effort to put economic logic to it. If you find the logic wanting, well, then you know more surely that it will end badly.

recession

unemployment

coronavirus

stimulus

fed

trump

testing

gdp

interest rates

unemployment

stimulus

Read More