Uncategorized

Why You Are Feeling So Much Poorer

Why You Are Feeling So Much Poorer

Authored by Jeffrey A. Tucker via The Epoch Times,

We are living through the largest pillaging of the…

Authored by Jeffrey A. Tucker via The Epoch Times,

We are living through the largest pillaging of the American middle class in a half-century. It’s not in the headlines. This is extremely strange. In fact, this might be the first and only article you have read about it. This could be for a reason. If people knew what was happening to them, they would begin to feel very restless, even furious. Some people among the ruling class do not want that.

The Biden administration trumpets its economic achievements. It’s mind-boggling. Call it trolling. Call it gaslighting. Call it whatever you want but you know it is untrue.

Let’s look at the facts.

What do you spend money on month-to-month? It’s rent or your mortgage, food at home or out, utilities, and gas. Those are the basic categories. The Consumer Price Index includes far more than that, some items you do not purchase and some that are going up far less than others. So let’s look at government numbers on what you actually purchase; that is, the items and services that you consume that dominate part of your income. And let’s stretch that back three years.

Everything is going up and up and has been for three years. Looking at the items on which you actually spend money, we find increases between 18-plus percent to 22-plus percent. Let’s say we average it all out at 20 percent.

Now let’s look at real disposable income, which is income left over after expenses adjusted for inflation. That result is an increase of a pathetic 3 percent compared with three years ago. The stimulus payments felt great at the time but those are long gone, essentially a head fake. So your income demands are up 20 percent whereas your leftover cash is barely up at all. That’s essentially a disaster for your standard of living.

In short, you have been robbed.

The causal reasons are many but mainly trace to the 43 percent increase in the money supply in the same period, which ate the value of the dollar with a lag. On top of that, supply chains broke, industry was consolidated, commercial freedom wrecked, and labor markets were forcibly disrupted.

Now, let’s compare this to what everyone recognizes as the great inflationary disaster of the postwar period, which is 1978 to 1982. These were the times when the Fed and government pillaged the public, drained away the value of savings and capital, and forced a reorganization of family life. At the end of this period, the average American household went from living off of one income—realizing the American dream—to having two incomes in the household. That happened in 1985 when two-income households became the norm.

At the time, this was called emancipation of women but, looking back, we can see that this was clearly propaganda to cover up an economic disaster. Gender discrimination in the workplace hasn’t really been a major issue for most of the 20th century. Back in the mid-1920s, if you look at unmarried women without children after the age of 18, the employment rate in the city was generally 80 percent. These women left the workforce upon marriage to focus on children and the household whereas the men bore the obligation of providing for the whole.

That was the way we lived until the great inflation. That’s what changed everything. After that, households had to have two incomes to live well instead of one, meaning that one partner had to go to the office rather than tend to the household or otherwise pursue the good life. That the ruling class was able to fob this off as some kind of new liberty (for women) is a tribute to the power of ideologically driven lies.

How do our times compare to then? Well, in three years, we’ve seen the value of the dollar fall 20 percent in terms of what you actually spend money on while income has barely gone up at all. During the great disaster of 43 years ago, this exact same phenomenon occurred over two years rather than three like our own times. In other words, the mass thievery in our times is taking place 50 percent slower than it happened last time. But it is happening nonetheless.

Is it any better if the bus rolls over you slowly or more quickly? It happens either way. That you lose 17 percent of your income in three years or two, what does it really matter? It is only valuable to our ruling-class masters in terms of the extent to which the public complains. A population pillaged slowly—like the frog boiling slowly—is very liable to complain a bit less. Still, the reality is the same.

The great inflation fundamentally changed life in America. We were never the same, economically or culturally. And that raises the real question: what is the current round of thievery going to do to this generation? I wish I had the answers. I don’t really know but we are seeing population-wide demoralization, ill-health, lack of ambition, substance abuse, and widespread despair. However this ends, it’s not going to be good.

Can this be turned around? Yes, but it won’t be easy. It will require massive changes in public administration the likes of which we’ve never experienced. No candidate for office at any level is prepared for what is necessary to reduce the debt, contain the Fed, defang the administrative bureaucracy, reduce the tax burden, and make the American dream affordable again. We are nowhere near speaking the truth at this point.

The emergency, however, is real. A people dealing with growing and relentless improvement, from powers out of their control, can be unpredictable. At a very minimum, it means more crime, more cultural anomie, more distrust, and growing anger. Some leader needs to channel this into a positive and constructive direction else we are doomed to suffer another round that will make the great inflation of the late 1970s look like a mere foreshadowing.

Uncategorized

Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more

New Zillow research suggests the spring home shopping season may see a second wave this summer if mortgage rates fall

The post Homes listed for sale in…

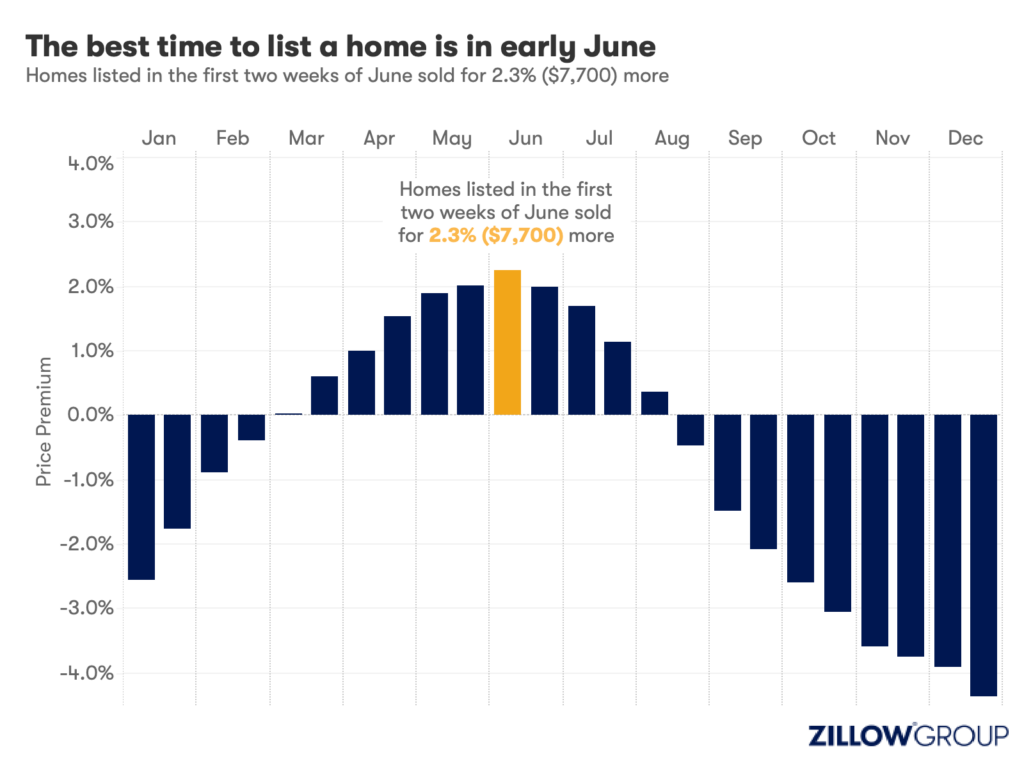

- A Zillow analysis of 2023 home sales finds homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more.

- The best time to list a home for sale is a month later than it was in 2019, likely driven by mortgage rates.

- The best time to list can be as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York and Philadelphia.

Spring home sellers looking to maximize their sale price may want to wait it out and list their home for sale in the first half of June. A new Zillow® analysis of 2023 sales found that homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more, a $7,700 boost on a typical U.S. home.

The best time to list consistently had been early May in the years leading up to the pandemic. The shift to June suggests mortgage rates are strongly influencing demand on top of the usual seasonality that brings buyers to the market in the spring. This home-shopping season is poised to follow a similar pattern as that in 2023, with the potential for a second wave if the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates midyear or later.

The 2.3% sale price premium registered last June followed the first spring in more than 15 years with mortgage rates over 6% on a 30-year fixed-rate loan. The high rates put home buyers on the back foot, and as rates continued upward through May, they were still reassessing and less likely to bid boldly. In June, however, rates pulled back a little from 6.79% to 6.67%, which likely presented an opportunity for determined buyers heading into summer. More buyers understood their market position and could afford to transact, boosting competition and sale prices.

The old logic was that sellers could earn a premium by listing in late spring, when search activity hit its peak. Now, with persistently low inventory, mortgage rate fluctuations make their own seasonality. First-time home buyers who are on the edge of qualifying for a home loan may dip in and out of the market, depending on what’s happening with rates. It is almost certain the Federal Reserve will push back any interest-rate cuts to mid-2024 at the earliest. If mortgage rates follow, that could bring another surge of buyers later this year.

Mortgage rates have been impacting affordability and sale prices since they began rising rapidly two years ago. In 2022, sellers nationwide saw the highest sale premium when they listed their home in late March, right before rates barreled past 5% and continued climbing.

Zillow’s research finds the best time to list can vary widely by metropolitan area. In 2023, it was as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York. Thirty of the top 35 largest metro areas saw for-sale listings command the highest sale prices between May and early July last year.

Zillow also found a wide range in the sale price premiums associated with homes listed during those peak periods. At the hottest time of the year in San Jose, homes sold for 5.5% more, a $88,000 boost on a typical home. Meanwhile, homes in San Antonio sold for 1.9% more during that same time period.

| Metropolitan Area | Best Time to List | Price Premium | Dollar Boost |

| United States | First half of June | 2.3% | $7,700 |

| New York, NY | First half of July | 2.4% | $15,500 |

| Los Angeles, CA | First half of May | 4.1% | $39,300 |

| Chicago, IL | First half of June | 2.8% | $8,800 |

| Dallas, TX | First half of June | 2.5% | $9,200 |

| Houston, TX | Second half of April | 2.0% | $6,200 |

| Washington, DC | Second half of June | 2.2% | $12,700 |

| Philadelphia, PA | First half of July | 2.4% | $8,200 |

| Miami, FL | First half of June | 2.3% | $12,900 |

| Atlanta, GA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $8,700 |

| Boston, MA | Second half of May | 3.5% | $23,600 |

| Phoenix, AZ | First half of June | 3.2% | $14,700 |

| San Francisco, CA | Second half of February | 4.2% | $50,300 |

| Riverside, CA | First half of May | 2.7% | $15,600 |

| Detroit, MI | First half of July | 3.3% | $7,900 |

| Seattle, WA | First half of June | 4.3% | $31,500 |

| Minneapolis, MN | Second half of May | 3.7% | $13,400 |

| San Diego, CA | Second half of April | 3.1% | $29,600 |

| Tampa, FL | Second half of June | 2.1% | $8,000 |

| Denver, CO | Second half of May | 2.9% | $16,900 |

| Baltimore, MD | First half of July | 2.2% | $8,200 |

| St. Louis, MO | First half of June | 2.9% | $7,000 |

| Orlando, FL | First half of June | 2.2% | $8,700 |

| Charlotte, NC | Second half of May | 3.0% | $11,000 |

| San Antonio, TX | First half of June | 1.9% | $5,400 |

| Portland, OR | Second half of April | 2.6% | $14,300 |

| Sacramento, CA | First half of June | 3.2% | $17,900 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $4,700 |

| Cincinnati, OH | Second half of April | 2.7% | $7,500 |

| Austin, TX | Second half of May | 2.8% | $12,600 |

| Las Vegas, NV | First half of June | 3.4% | $14,600 |

| Kansas City, MO | Second half of May | 2.5% | $7,300 |

| Columbus, OH | Second half of June | 3.3% | $10,400 |

| Indianapolis, IN | First half of July | 3.0% | $8,100 |

| Cleveland, OH | First half of July | 3.4% | $7,400 |

| San Jose, CA | First half of June | 5.5% | $88,400 |

The post Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more appeared first on Zillow Research.

federal reserve pandemic home sales mortgage rates interest ratesUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

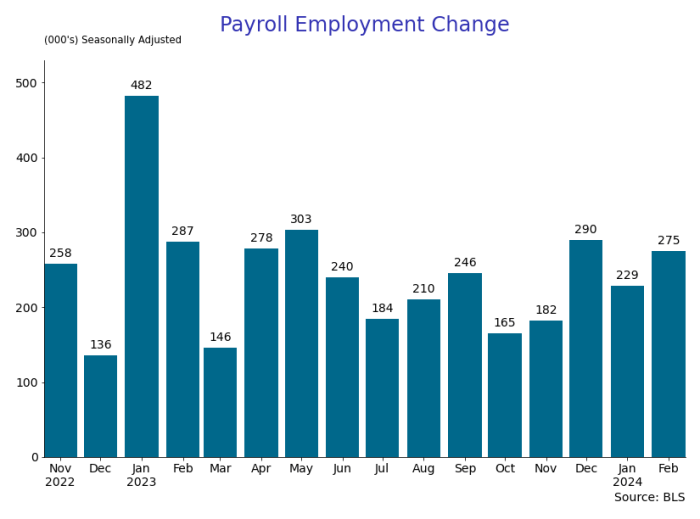

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

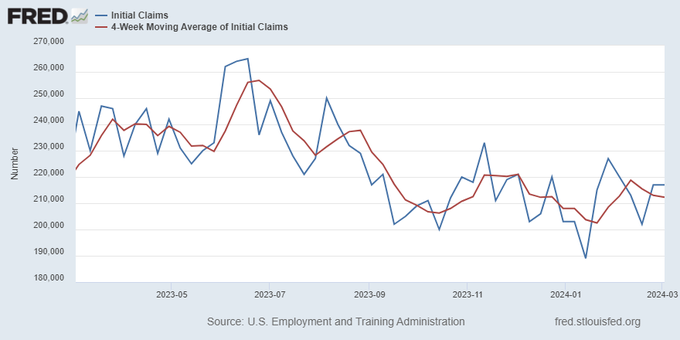

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemployment-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex