International

“This Is Astounding”: China Is Snapping Up Most Of The World’s “Missing” Barrels Of Oil

"This Is Astounding": China Is Snapping Up Most Of The World’s "Missing" Barrels Of Oil

Tyler Durden

Tue, 12/08/2020 – 21:45

In almost every oil cycle, the market is confronted with the problem of "missing barrels", or the gap betwe

In almost every oil cycle, the market is confronted with the problem of "missing barrels", or the gap between the change in inventory implied by global supply-demand balances on the one hand and the observed change in inventory levels by commercial and government entities (adjusted for floating storage and oil in transit) on the other hand.

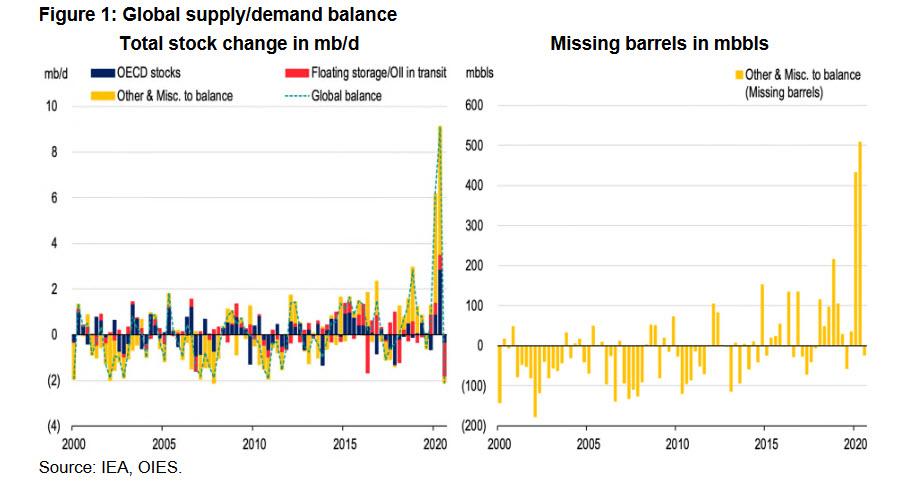

As the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies writes in a report published today, based on IEA global oil balances, the surplus during the first three quarters of 2020 averaged around 4.4 mb/d, with the surplus in the first half of 2020 reaching a record level of 7.6 mb/d due to the severity of the demand shock and the break-up of the OPEC+ agreement in March. This implies an inventory increase in H1 2020 of 1,390 million barrels (mbbls), before declining by 194.2 mbbls in Q3.

According to the IEA, out of the total stockbuild in the first half of the year, total OECD stocks accounted for 344.3 mbbls or 25% of the total increase, floating storage and oil in transit accounted for 105.3 mbbls or 8% of the total increase and the remaining 940.4 mbbls or 68% of the total increase to balance is essentially unaccounted for including changes in non-reported stocks in OECD and non-OECD areas that the IEA labels as "Other & Miscellaneous to balance" (as shown in Figure 1).

The volume of missing barrels in H1 2020, the OIES writes, "is the largest ever recorded gap between observed and implied stocks since at least 1990, being three times larger than previous historical downcycles such as in H1 1998 and more recently the H2 2018 downturn and nearly 10 times larger than the imbalance of H2 2008 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis."

The "missing barrels" problem can arise due to a number of factors. The most obvious reason is that models could be generating "artificial barrels" by underestimating demand and overestimating supply. The severity of the oil crisis in 2020 due to the global coronavirus pandemic led to the break of some key relationships (for instance between economic growth and oil demand) and models had to be calibrated to account for the severity of the shock (for instance, including indicators of the severity of restrictions across countries).

Another factor is the coverage and quality of data on stocks. The reason for this is that very little publicly reported, accurate information exists for oil stocks outside of the United States. And yet the US oil stocks many not be an accurate reflection of the world situation. This observation increasingly holds as demand growth has shifted from OECD to non-OECD, especially given the key role that China is playing in global crude demand. In this latest cycle, China’s position as a key equilibrating mechanism was further highlighted as it absorbed surplus barrels from all over the world as it took advantage of relatively cheap crude to fill its large and growing storage capacity.

To put this in perspective, OIES utilized crude inventory and fleet metrics data from Kpler and attempted to identify some of the missing barrels implied from IEA balances. As Figure 2 shows, even accounting for additional floating storage and oil in transit (+250.4 mbbls), as well as OECD and non-OECD crude stock changes excluding China (+85.2 mbbls), all of which are not previously reported by IEA, we are still missing 597.8 mbbls or 64% of the total missing barrels in H1 2020. This issue becomes more complex in Q3 2020 for which the IEA balances imply a 194.2 mbbls deficit of which 171.3 mbbls are accounted for and 22.9 mbbls are missing. Kpler data, however, show a much larger draw of floating storage, suggesting one (or a combination) of three possibilities: the actual deficit is much larger than estimated by the IEA (by about 150 mbbls); there was a large build in non-OECD stocks, or the implied market surplus in H1 2020 was overestimated and carried over. Indeed, a large build in unaccountable stocks in Q2 2020 followed by a draw in Q3 2020 suggests that barrels were stored and drawn in places where they currently cannot be tracked.

The China Conundrum

The issue of "missing barrels" has long plagued Chinese data, but much like in the rest of the world, has become more pressing and perplexing in 2020. Net crude imports in the year-to-October averaged 11.09 mb/d, rising from 2019 levels by over 1 mb/d and maintaining their 2019 growth rates. According to the OIES report, "this is astounding given that economic activity has been considerably weaker and runs have averaged 13.3 mb/d in the first ten months of 2020, growing by an impressive 0.47 mb/d, but still lower than the 0.82 mb/d increment seen over the same period last year."

Put simply: the data suggest China has overbought crude to put in storage.

But the key question is, how much has gone into storage and perhaps more critically, how much is likely to come back out?

In response to this rhetorical question, the Oxford Institute authors notes that assessing how much crude has gone into storage has become both an art and a science, given the limited official data. When looking at implied stockbuilds (i.e deducting crude used for refinery runs from the sum of domestic production and net imports), in the year-to-October, China has stored on average 1.6 mb/d, or a staggering 488 mbbls of crude.

While it has been clear that large volumes of crude oil have headed to China, judging by port congestion at Chinese shores, differentials and benchmarks, such volumes seem overstated as they would have likely led to tank tops earlier this year. According to OIES estimates, China had close to 1,100 mbbls of crude storage capacity at the end of 2019 (that's over 1.1 billion and far, far more than Cushing and the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve). Assuming a roughly 60% utilization rate, crude stocks would have reached 650-680 mbbls. A build of an additional 500 mbbls, even when taking into account 250 mb of new tank space added over the year, would have overwhelmed China’s storage capacity leading to a slowdown in crude arrivals already earlier this year.

And even though imports into China are slowing somewhat and storage utilization rates are likely at over 75% currently, there are signs of a recovery in crude buying for early 2021. It is therefore useful to look more closely at implied stockbuilds.

First, many crude balances for China do not account for crude losses during the refining process or burnt at the field, which between 2000 and 2017, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, have averaged 0.30 mb/d8. In the five years prior to 2017, losses in refining increased to average 0.35 mb/d, so when deducting these losses, the implied stockbuild for the year-to-date falls to an average 1.3 mb/d, or just over 375 mbbls. While this is still a monumental build, it is more plausible.

At the same time, Chinese demand could also be underestimated. China’s independent refiners have been infamous for tax evasion and especially between 2016 and 2018 were estimated to have underreported refining throughputs by 0.3-0.8 mb/d10. So historically, Chinese crude demand has been understated. The shift to new tax reporting practices in early 2018 have limited the independents’ ability to under report runs, although a number of them subsequently turned to misrepresenting their product output. In late 2020, following an announcement by Shandong officials that they will be levying a windfall tax this year, which is based on product output, the independents may be resorting to some under reporting again, although any such volumes are likely small, given that China’s demand is recovering slowly and product tanks are also estimated to be two-thirds full. Some combination, therefore, of underestimated demand and crude in storage suggests that China could well be responsible for as much as half of the missing barrels and that these are indeed "real."

The next question is then, how likely are these barrels to be drawn down, and will they weigh on Chinese imports?

Roughly a third of these volumes could have gone into bonded tanks. When looking at China’s crude imports, there is a discrepancy between waterborne flows as assessed by Kpler and arrivals reported by customs data, with assessed arrivals higher than customs data by 0.47 mb/d for the year-to-October (Figure 3). In previous years, the difference in assessed volumes and customs data were smaller, mostly due to discrepancies between the timings of arrival and discharge, alongside some crude going into bonded tanks.

This year, the discrepancy is more substantial and points to a large accumulation of crude in bonded tanks, which are not consistently counted as imports. Not only has the INE increased its storage capacity this year, with its tanks holding 34 mb of crude at the end of October according to the exchange but sanctioned barrels may have also gone into bonded tanks. For example, in the year-to-October, Kpler estimates point to 0.15 mb/d of Iranian crude going to China (compared to 75,000 b/d recorded by customs) as well as 0.21 mb/d of Venezuelan crude flowing to the country (although customs have reported no Venezuelan crude going into China). Theoretically, then, at the end of October, China had accumulated as much as 85 mb of Iranian and Venezuelan crude in bonded storage tanks over the course of the year, although some of these will have likely been drawn down by refiners, and if they have not been yet, they will be.

But that still leaves over 200 mbbls of crude in storage, of which only a fraction is likely to return to the market. This is because these volumes have gone into both commercial and strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) tanks that are used as buffer, both for refiners’ forward cover and strategic reserves. China has a small number of designated SPR tanks of close to 400 mbbls, that are likely 300 mbbls full, with Argus estimating 32 mbbls of fills this year alone (see Figure 4). At the same time, the government has been leasing out commercial tank space for its SPR programme, as the construction of dedicated SPR sites has been slow. But even with close to 150 mbbls of commercial tanks that are widely assumed to be leased out to the SPR, the SPR program only meets around 40 days of import cover (as 90 days at current import volumes would imply over 1,000 mbbls).

In addition, China’s refiners are mandated to hold 15 days of forward cover, which, for a system of close to 19 mb/d of nameplate capacity, means almost 300 mbbls of forward cover. Indeed, part of the increase in import licences awarded to non-state refiners this year was intended for them to build up their crude stocks while prices remain at relatively low levels.

In sum, when taking into account the crude requirements of storage tanks at the various ports and other commercial sites as well as pipeline fills, the crude requirement for China’s oil system is massive. As a result, most of the crude flowing into China this year has helped meet these needs. All in all, we estimate China now holds close to 1,000 mbbls in storage, which is roughly 90 days of its import needs, with capacity by year end reaching 1,300-1,400 mbbls. The good news for markets is that only a small part of these barrels will be drawn down, but the bad news is that China’s future stockpiling needs are now shrinking.

This is not to say that China’s crude imports will fall: with over 1 mb/d of new refining capacity starting up over the next two years, refiners will continue sourcing crude as refining throughputs continue to rise and as new plants require operating stocks. Moreover, additional infrastcuture including tanks and pipelines will need filling. But over the next two years, incremental demand for strategic stocks will slow, and crude imports will become more closely aligned with refiners’ needs.

Conclusion

The large accumulation of barrels in China suggests that "artificial" or "imaginary" barrels, as a result of imprecise measurement of global oil supply-demand balances, are not the only explanation to the missing barrels question. Indeed, even though China’s crude balances are riddled with inconsistencies, it is clear that the country has amassed large volumes of crude this year — potentially close to 400 mbbls — which have contributed both to the country’s strategic reserves and commercial forward cover. At the same time, Chinese demand may well be underestimated given refiners’ tax avoidance practices. So, as global supply and demand numbers get adjusted with the arrival of new information — which likely includes other Asian countries for which both demand and storage estimates are imperfect — the volume of missing barrels will shrink further, if indeed half have ended up in Chinese storage tanks and are unlikely to be released back into the market. In addition, some of the missing barrels are a result of unobservable barrels in important consuming centers and perhaps also stocks held at the distribution level and by final end consumers.

As the Oxford researchers conclude, "the complexities of global crude balances, despite the important contribution made by new technologies, highlight the ongoing challenges facing OPEC+ in estimating how long it will take to rebalance the market. In addition to the uncertainties surrounding the demand outlook in these unprecedented times, assessing the extent and nature of buffers in the system has become more complicated."

The question is whether going forward, OPEC+ can afford to ignore non-OECD stocks? And if these stocks are being stored for strategic purposes and the bulk of these stocks will not be released back into the market, does targeting non-OECD stocks really matter for oil policy purposes? Should we exclude years of elevated stocks from the averages or have these become main features of the new cycles and the adjustment process? As we enter 2021 in an environment of extremely depressed oil demand, these questions will become more pressing.

International

Rand Paul Teases Senate GOP Leader Run – Musk Says “I Would Support”

Rand Paul Teases Senate GOP Leader Run – Musk Says "I Would Support"

Republican Kentucky Senator Rand Paul on Friday hinted that he may jump…

Republican Kentucky Senator Rand Paul on Friday hinted that he may jump into the race to become the next Senate GOP leader, and Elon Musk was quick to support the idea. Republicans must find a successor for periodically malfunctioning Mitch McConnell, who recently announced he'll step down in November, though intending to keep his Senate seat until his term ends in January 2027, when he'd be within weeks of turning 86.

So far, the announced field consists of two quintessential establishment types: John Cornyn of Texas and John Thune of South Dakota. While John Barrasso's name had been thrown around as one of "The Three Johns" considered top contenders, the Wyoming senator on Tuesday said he'll instead seek the number two slot as party whip.

Paul used X to tease his potential bid for the position which -- if the GOP takes back the upper chamber in November -- could graduate from Minority Leader to Majority Leader. He started by telling his 5.1 million followers he'd had lots of people asking him about his interest in running...

Thousands of people have been asking if I'd run for Senate leadership...

— Rand Paul (@RandPaul) March 8, 2024

...then followed up with a poll in which he predictably annihilated Cornyn and Thune, taking a 96% share as of Friday night, with the other two below 2% each.

????????️VOTE NOW ????️ ???? Who would you like to be the next Senate leader?

— Rand Paul (@RandPaul) March 8, 2024

Elon Musk was quick to back the idea of Paul as GOP leader, while daring Cornyn and Thune to follow Paul's lead by throwing their names out for consideration by the Twitter-verse X-verse.

I would support Rand Paul and suspect that other candidates will not actually run polls out of concern for the results, but let’s see if they will!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 8, 2024

Paul has been a stalwart opponent of security-state mass surveillance, foreign interventionism -- to include shoveling billions of dollars into the proxy war in Ukraine -- and out-of-control spending in general. He demonstrated the latter passion on the Senate floor this week as he ridiculed the latest kick-the-can spending package:

This bill is an insult to the American people. The earmarks are all the wasteful spending that you could ever hope to see, and it should be defeated. Read more: https://t.co/Jt8K5iucA4 pic.twitter.com/I5okd4QgDg

— Senator Rand Paul (@SenRandPaul) March 8, 2024

In February, Paul used Senate rules to force his colleagues into a grueling Super Bowl weekend of votes, as he worked to derail a $95 billion foreign aid bill. "I think we should stay here as long as it takes,” said Paul. “If it takes a week or a month, I’ll force them to stay here to discuss why they think the border of Ukraine is more important than the US border.”

Don't expect a Majority Leader Paul to ditch the filibuster -- he's been a hardy user of the legislative delay tactic. In 2013, he spoke for 13 hours to fight the nomination of John Brennan as CIA director. In 2015, he orated for 10-and-a-half-hours to oppose extension of the Patriot Act.

Among the general public, Paul is probably best known as Capitol Hill's chief tormentor of Dr. Anthony Fauci, who was director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease during the Covid-19 pandemic. Paul says the evidence indicates the virus emerged from China's Wuhan Institute of Virology. He's accused Fauci and other members of the US government public health apparatus of evading questions about their funding of the Chinese lab's "gain of function" research, which takes natural viruses and morphs them into something more dangerous. Paul has pointedly said that Fauci committed perjury in congressional hearings and that he belongs in jail "without question."

Musk is neither the only nor the first noteworthy figure to back Paul for party leader. Just hours after McConnell announced his upcoming step-down from leadership, independent 2024 presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Jr voiced his support:

Mitch McConnell, who has served in the Senate for almost 40 years, announced he'll step down this November.

— Robert F. Kennedy Jr (@RobertKennedyJr) February 28, 2024

Part of public service is about knowing when to usher in a new generation. It’s time to promote leaders in Washington, DC who won’t kowtow to the military contractors or…

In a testament to the extent to which the establishment recoils at the libertarian-minded Paul, mainstream media outlets -- which have been quick to report on other developments in the majority leader race -- pretended not to notice that Paul had signaled his interest in the job. More than 24 hours after Paul's test-the-waters tweet-fest began, not a single major outlet had brought it to the attention of their audience.

That may be his strongest endorsement yet.

Spread & Containment

‘I couldn’t stand the pain’: the Turkish holiday resort that’s become an emergency dental centre for Britons who can’t get treated at home

The crisis in NHS dentistry is driving increasing numbers abroad for treatment. Here are some of their stories.

It’s a hot summer day in the Turkish city of Antalya, a Mediterranean resort with golden beaches, deep blue sea and vibrant nightlife. The pool area of the all-inclusive resort is crammed with British people on sun loungers – but they aren’t here for a holiday. This hotel is linked to a dental clinic that organises treatment packages, and most of these guests are here to see a dentist.

From Norwich, two women talk about gums and injections. A man from Wales holds a tissue close to his mouth and spits blood – he has just had two molars extracted.

The dental clinic organises everything for these dental “tourists” throughout their treatment, which typically lasts from three to 15 days. The stories I hear of what has caused them to travel to Turkey are strikingly similar: all have struggled to secure dental treatment at home on the NHS.

“The hotel is nice and some days I go to the beach,” says Susan*, a hairdresser in her mid-30s from Norwich. “But really, we aren’t tourists like in a proper holiday. We come here because we have no choice. I couldn’t stand the pain.”

This is Susan’s second visit to Antalya. She explains that her ordeal started two years earlier:

I went to an NHS dentist who told me I had gum disease … She did some cleaning to my teeth and gums but it got worse. When I ate, my teeth were moving … the gums were bleeding and it was very painful. I called to say I was in pain but the clinic was not accepting NHS patients any more.

The only option the dentist offered Susan was to register as a private patient:

I asked how much. They said £50 for x-rays and then if the gum disease got worse, £300 or so for extraction. Four of them were moving – imagine: £1,200 for losing your teeth! Without teeth I’d lose my clients, but I didn’t have the money. I’m a single mum. I called my mum and cried.

Susan’s mother told her about a friend of hers who had been to Turkey for treatment, then together they found a suitable clinic:

The prices are so much cheaper! Tooth extraction, x-rays, consultations – it all comes included. The flight and hotel for seven days cost the same as losing four teeth in Norwich … I had my lower teeth removed here six months ago, now I’ve got implants … £2,800 for everything – hotel, transfer, treatments. I only paid the flights separately.

In the UK, roughly half the adult population suffers from periodontitis – inflammation of the gums caused by plaque bacteria that can lead to irreversible loss of gums, teeth, and bone. Regular reviews by a dentist or hygienist are required to manage this condition. But nine out of ten dental practices cannot offer NHS appointments to new adult patients, while eight in ten are not accepting new child patients.

Some UK dentists argue that Britons who travel abroad for treatment do so mainly for cosmetic procedures. They warn that dental tourism is dangerous, and that if their treatment goes wrong, dentists in the UK will be unable to help because they don’t want to be responsible for further damage. Susan shrugs this off:

Dentists in England say: ‘If you go to Turkey, we won’t touch you [afterwards].’ But I don’t worry because there are no appointments at home anyway. They couldn’t help in the first place, and this is why we are in Turkey.

‘How can we pay all this money?’

As a social anthropologist, I travelled to Turkey a number of times in 2023 to investigate the crisis of NHS dentistry, and the journeys abroad that UK patients are increasingly making as a result. I have relatives in Istanbul and have been researching migration and trading patterns in Turkey’s largest city since 2016.

In August 2023, I visited the resort in Antalya, nearly 400 miles south of Istanbul. As well as Susan, I met a group from a village in Wales who said there was no provision of NHS dentistry back home. They had organised a two-week trip to Turkey: the 12-strong group included a middle-aged couple with two sons in their early 20s, and two couples who were pensioners. By going together, Anya tells me, they could support each other through their different treatments:

I’ve had many cavities since I was little … Before, you could see a dentist regularly – you didn’t even think about it. If you had pain or wanted a regular visit, you phoned and you went … That was in the 1990s, when I went to the dentist maybe every year.

Anya says that once she had children, her family and work commitments meant she had no time to go to the dentist. Then, years later, she started having serious toothache:

Every time I chewed something, it hurt. I ate soups and soft food, and I also lost weight … Even drinking was painful – tea: pain, cold water: pain. I was taking paracetamol all the time! I went to the dentist to fix all this, but there were no appointments.

Anya was told she would have to wait months, or find a dentist elsewhere:

A private clinic gave me a list of things I needed done. Oh my God, almost £6,000. My husband went too – same story. How can we pay all this money? So we decided to come to Turkey. Some people we know had been here, and others in the village wanted to come too. We’ve brought our sons too – they also need to be checked and fixed. Our whole family could be fixed for less than £6,000.

By the time they travelled, Anya’s dental problems had turned into a dental emergency. She says she could not live with the pain anymore, and was relying on paracetamol.

In 2023, about 6 million adults in the UK experienced protracted pain (lasting more than two weeks) caused by toothache. Unintentional paracetamol overdose due to dental pain is a significant cause of admissions to acute medical units. If left untreated, tooth infections can spread to other parts of the body and cause life-threatening complications – and on rare occasions, death.

In February 2024, police were called to manage hundreds of people queuing outside a newly opened dental clinic in Bristol, all hoping to be registered or seen by an NHS dentist. One in ten Britons have admitted to performing “DIY dentistry”, of which 20% did so because they could not find a timely appointment. This includes people pulling out their teeth with pliers and using superglue to repair their teeth.

In the 1990s, dentistry was almost entirely provided through NHS services, with only around 500 solely private dentists registered. Today, NHS dentist numbers in England are at their lowest level in a decade, with 23,577 dentists registered to perform NHS work in 2022-23, down 695 on the previous year. Furthermore, the precise division of NHS and private work that each dentist provides is not measured.

The COVID pandemic created longer waiting lists for NHS treatment in an already stretched public service. In Bridlington, Yorkshire, people are now reportedly having to wait eight-to-nine years to get an NHS dental appointment with the only remaining NHS dentist in the town.

In his book Patients of the State (2012), Argentine sociologist Javier Auyero describes the “indignities of waiting”. It is the poor who are mostly forced to wait, he writes. Queues for state benefits and public services constitute a tangible form of power over the marginalised. There is an ethnic dimension to this story, too. Data suggests that in the UK, patients less likely to be effective in booking an NHS dental appointment are non-white ethnic groups and Gypsy or Irish travellers, and that it is particularly challenging for refugees and asylum-seekers to access dental care.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

In 2022, I experienced my own dental emergency. An infected tooth was causing me debilitating pain, and needed root canal treatment. I was advised this would cost £71 on the NHS, plus £307 for a follow-up crown – but that I would have to wait months for an appointment. The pain became excruciating – I could not sleep, let alone wait for months. In the same clinic, privately, I was quoted £1,300 for the treatment (more than half my monthly income at the time), or £295 for a tooth extraction.

I did not want to lose my tooth because of lack of money. So I bought a flight to Istanbul immediately for the price of the extraction in the UK, and my tooth was treated with root canal therapy by a private dentist there for £80. Including the costs of travelling, the total was a third of what I was quoted to be treated privately in the UK. Two years on, my treated tooth hasn’t given me any more problems.

A better quality of life

Not everyone is in Antalya for emergency procedures. The pensioners from Wales had contacted numerous clinics they found on the internet, comparing prices, treatments and hotel packages at least a year in advance, in a carefully planned trip to get dental implants – artificial replacements for tooth roots that help support dentures, crowns and bridges.

In Turkey, all the dentists I speak to (most of whom cater mainly for foreigners, including UK nationals) consider implants not a cosmetic or luxurious treatment, but a development in dentistry that gives patients who are able to have the procedure a much better quality of life. This procedure is not available on the NHS for most of the UK population, and the patients I meet in Turkey could not afford implants in private clinics back home.

Paul is in Antalya to replace his dentures, which have become uncomfortable and irritating to his gums, with implants. He says he couldn’t find an appointment to see an NHS dentist. His wife Sonia went through a similar procedure the year before and is very satisfied with the results, telling me: “Why have dentures that you need to put in a glass overnight, in the old style? If you can have implants, I say, you’re better off having them.”

Most of the dental tourists I meet in Antalya are white British: this city, known as the Turkish Riviera, has developed an entire economy catering to English-speaking tourists. In 2023, more than 1.3 million people visited the city from the UK, up almost 15% on the previous year.

Read more: NHS dentistry is in crisis – are overseas dentists the answer?

In contrast, the Britons I meet in Istanbul are predominantly from a non-white ethnic background. Omar, a pensioner of Pakistani origin in his early 70s, has come here after waiting “half a year” for an NHS appointment to fix the dental bridge that is causing him pain. Omar’s son had been previously for a hair transplant, and was offered a free dental checkup by the same clinic, so he suggested it to his father. Having worked as a driver for a manufacturing company for two decades in Birmingham, Omar says he feels disappointed to have contributed to the British economy for so long, only to be “let down” by the NHS:

At home, I must wait and wait and wait to get a bridge – and then I had many problems with it. I couldn’t eat because the bridge was uncomfortable and I was in pain, but there were no appointments on the NHS. I asked a private dentist and they recommended implants, but they are far too expensive [in the UK]. I started losing weight, which is not a bad thing at the beginning, but then I was worrying because I couldn’t chew and eat well and was losing more weight … Here in Istanbul, I got dental implants – US$500 each, problem solved! In England, each implant is maybe £2,000 or £3,000.

In the waiting area of another clinic in Istanbul, I meet Mariam, a British woman of Iraqi background in her late 40s, who is making her second visit to the dentist here. Initially, she needed root canal therapy after experiencing severe pain for weeks. Having been quoted £1,200 in a private clinic in outer London, Mariam decided to fly to Istanbul instead, where she was quoted £150 by a dentist she knew through her large family. Even considering the cost of the flight, Mariam says the decision was obvious:

Dentists in England are so expensive and NHS appointments so difficult to find. It’s awful there, isn’t it? Dentists there blamed me for my rotten teeth. They say it’s my fault: I don’t clean or I ate sugar, or this or that. I grew up in a village in Iraq and didn’t go to the dentist – we were very poor. Then we left because of war, so we didn’t go to a dentist … When I arrived in London more than 20 years ago, I didn’t speak English, so I still didn’t go to the dentist … I think when you move from one place to another, you don’t go to the dentist unless you are in real, real pain.

In Istanbul, Mariam has opted not only for the urgent root canal treatment but also a longer and more complex treatment suggested by her consultant, who she says is a renowned doctor from Syria. This will include several extractions and implants of back and front teeth, and when I ask what she thinks of achieving a “Hollywood smile”, Mariam says:

Who doesn’t want a nice smile? I didn’t come here to be a model. I came because I was in pain, but I know this doctor is the best for implants, and my front teeth were rotten anyway.

Dentists in the UK warn about the risks of “overtreatment” abroad, but Mariam appears confident that this is her opportunity to solve all her oral health problems. Two of her sisters have already been through a similar treatment, so they all trust this doctor.

The UK’s ‘dental deserts’

To get a fuller understanding of the NHS dental crisis, I’ve also conducted 20 interviews in the UK with people who have travelled or were considering travelling abroad for dental treatment.

Joan, a 50-year-old woman from Exeter, tells me she considered going to Turkey and could have afforded it, but that her back and knee problems meant she could not brave the trip. She has lost all her lower front teeth due to gum disease and, when I meet her, has been waiting 13 months for an NHS dental appointment. Joan tells me she is living in “shame”, unable to smile.

In the UK, areas with extremely limited provision of NHS dental services – known as as “dental deserts” – include densely populated urban areas such as Portsmouth and Greater Manchester, as well as many rural and coastal areas.

In Felixstowe, the last dentist taking NHS patients went private in 2023, despite the efforts of the activist group Toothless in Suffolk to secure better access to NHS dentists in the area. It’s a similar story in Ripon, Yorkshire, and in Dumfries & Galloway, Scotland, where nearly 25,000 patients have been de-registered from NHS dentists since 2021.

Data shows that 2 million adults must travel at least 40 miles within the UK to access dental care. Branding travel for dental care as “tourism” carries the risk of disguising the elements of duress under which patients move to restore their oral health – nationally and internationally. It also hides the immobility of those who cannot undertake such journeys.

The 90-year-old woman in Dumfries & Galloway who now faces travelling for hours by bus to see an NHS dentist can hardly be considered “tourism” – nor the Ukrainian war refugees who travelled back from West Sussex and Norwich to Ukraine, rather than face the long wait to see an NHS dentist.

Many people I have spoken to cannot afford the cost of transport to attend dental appointments two hours away – or they have care responsibilities that make it impossible. Instead, they are forced to wait in pain, in the hope of one day securing an appointment closer to home.

‘Your crisis is our business’

The indignities of waiting in the UK are having a big impact on the lives of some local and foreign dentists in Turkey. Some neighbourhoods are rapidly changing as dental and other health clinics, usually in luxurious multi-storey glass buildings, mushroom. In the office of one large Istanbul medical complex with sections for hair transplants and dentistry (plus one linked to a hospital for more extensive cosmetic surgery), its Turkish owner and main investor tells me:

Your crisis is our business, but this is a bazaar. There are good clinics and bad clinics, and unfortunately sometimes foreign patients do not know which one to choose. But for us, the business is very good.

This clinic only caters to foreign patients. The owner, an architect by profession who also developed medical clinics in Brazil, describes how COVID had a major impact on his business:

When in Europe you had COVID lockdowns, Turkey allowed foreigners to come. Many people came for ‘medical tourism’ – we had many patients for cosmetic surgery and hair transplants. And that was when the dental business started, because our patients couldn’t see a dentist in Germany or England. Then more and more patients started to come for dental treatments, especially from the UK and Ireland. For them, it’s very, very cheap here.

The reasons include the value of the Turkish lira relative to the British pound, the low cost of labour, the increasing competition among Turkish clinics, and the sheer motivation of dentists here. While most dentists catering to foreign patients are from Turkey, others have arrived seeking refuge from war and violence in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran and beyond. They work diligently to rebuild their lives, careers and lost wealth.

Regardless of their origin, all dentists in Turkey must be registered and certified. Hamed, a Syrian dentist and co-owner of a new clinic in Istanbul catering to European and North American patients, tells me:

I know that you say ‘Syrian’ and people think ‘migrant’, ‘refugee’, and maybe think ‘how can this dentist be good?’ – but Syria, before the war, had very good doctors and dentists. Many of us came to Turkey and now I have a Turkish passport. I had to pass the exams to practise dentistry here – I study hard. The exams are in Turkish and they are difficult, so you cannot say that Syrian doctors are stupid.

Hamed talks excitedly about the latest technology that is coming to his profession: “There are always new materials and techniques, and we cannot stop learning.” He is about to travel to Paris to an international conference:

I can say my techniques are very advanced … I bet I put more implants and do more bone grafting and surgeries every week than any dentist you know in England. A good dentist is about practice and hand skills and experience. I work hard, very hard, because more and more patients are arriving to my clinic, because in England they don’t find dentists.

While there is no official data about the number of people travelling from the UK to Turkey for dental treatment, investors and dentists I speak to consider that numbers are rocketing. From all over the world, Turkey received 1.2 million visitors for “medical tourism” in 2022, an increase of 308% on the previous year. Of these, about 250,000 patients went for dentistry. One of the most renowned dental clinics in Istanbul had only 15 British patients in 2019, but that number increased to 2,200 in 2023 and is expected to reach 5,500 in 2024.

Like all forms of medical care, dental treatments carry risks. Most clinics in Turkey offer a ten-year guarantee for treatments and a printed clinical history of procedures carried out, so patients can show this to their local dentists and continue their regular annual care in the UK. Dental treatments, checkups and maintaining a good oral health is a life-time process, not a one-off event.

Many UK patients, however, are caught between a rock and a hard place – criticised for going abroad, yet unable to get affordable dental care in the UK before and after their return. The British Dental Association has called for more action to inform these patients about the risks of getting treated overseas – and has warned UK dentists about the legal implications of treating these patients on their return. But this does not address the difficulties faced by British patients who are being forced to go abroad in search of affordable, often urgent dental care.

A global emergency

The World Health Organization states that the explosion of oral disease around the world is a result of the “negligent attitude” that governments, policymakers and insurance companies have towards including oral healthcare under the umbrella of universal healthcare. It as if the health of our teeth and mouth is optional; somehow less important than treatment to the rest of our body. Yet complications from untreated tooth decay can lead to hospitalisation.

The main causes of oral health diseases are untreated tooth decay, severe gum disease, toothlessness, and cancers of the lip and oral cavity. Cases grew during the pandemic, when little or no attention was paid to oral health. Meanwhile, the global cosmetic dentistry market is predicted to continue growing at an annual rate of 13% for the rest of this decade, confirming the strong relationship between socioeconomic status and access to oral healthcare.

In the UK since 2018, there have been more than 218,000 admissions to hospital for rotting teeth, of which more than 100,000 were children. Some 40% of children in the UK have not seen a dentist in the past 12 months. The role of dentists in prevention of tooth decay and its complications, and in the early detection of mouth cancer, is vital. While there is a 90% survival rate for mouth cancer if spotted early, the lack of access to dental appointments is causing cases to go undetected.

The reasons for the crisis in NHS dentistry are complex, but include: the real-term cuts in funding to NHS dentistry; the challenges of recruitment and retention of dentists in rural and coastal areas; pay inequalities facing dental nurses, most of them women, who are being badly hit by the cost of living crisis; and, in England, the 2006 Dental Contract that does not remunerate dentists in a way that encourages them to continue seeing NHS patients.

The UK is suffering a mass exodus of the public dentistry workforce, with workers leaving the profession entirely or shifting to the private sector, where payments and life-work balance are better, bureaucracy is reduced, and prospects for career development look much better. A survey of general dental practitioners found that around half have reduced their NHS work since the pandemic – with 43% saying they were likely to go fully private, and 42% considering a career change or taking early retirement.

Reversing the UK’s dental crisis requires more commitment to substantial reform and funding than the “recovery plan” announced by Victoria Atkins, the secretary of state for health and social care, on February 7.

The stories I have gathered show that people travelling abroad for dental treatment don’t see themselves as “tourists” or vanity-driven consumers of the “Hollywood smile”. Rather, they have been forced by the crisis in NHS dentistry to seek out a service 1,500 miles away in Turkey that should be a basic, affordable right for all, on their own doorstep.

*Names in this article have been changed to protect the anonymity of the interviewees.

For you: more from our Insights series:

GP crisis: how did things go so wrong, and what needs to change?

Insomnia: how chronic sleep problems can lead to a spiralling decline in mental health

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Diana Ibanez Tirado receives funding from the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex.

pound pandemic treatment therapy spread recovery iran brazil european europe uk germany ukraine world health organizationInternational

Beloved mall retailer files Chapter 7 bankruptcy, will liquidate

The struggling chain has given up the fight and will close hundreds of stores around the world.

It has been a brutal period for several popular retailers. The fallout from the covid pandemic and a challenging economic environment have pushed numerous chains into bankruptcy with Tuesday Morning, Christmas Tree Shops, and Bed Bath & Beyond all moving from Chapter 11 to Chapter 7 bankruptcy liquidation.

In all three of those cases, the companies faced clear financial pressures that led to inventory problems and vendors demanding faster, or even upfront payment. That creates a sort of inevitability.

Related: Beloved retailer finds life after bankruptcy, new famous owner

When a retailer faces financial pressure it sets off a cycle where vendors become wary of selling them items. That leads to barren shelves and no ability for the chain to sell its way out of its financial problems.

Once that happens bankruptcy generally becomes the only option. Sometimes that means a Chapter 11 filing which gives the company a chance to negotiate with its creditors. In some cases, deals can be worked out where vendors extend longer terms or even forgive some debts, and banks offer an extension of loan terms.

In other cases, new funding can be secured which assuages vendor concerns or the company might be taken over by its vendors. Sometimes, as was the case with David's Bridal, a new owner steps in, adds new money, and makes deals with creditors in order to give the company a new lease on life.

It's rare that a retailer moves directly into Chapter 7 bankruptcy and decides to liquidate without trying to find a new source of funding.

Image source: Getty Images

The Body Shop has bad news for customers

The Body Shop has been in a very public fight for survival. Fears began when the company closed half of its locations in the United Kingdom. That was followed by a bankruptcy-style filing in Canada and an abrupt closure of its U.S. stores on March 4.

"The Canadian subsidiary of the global beauty and cosmetics brand announced it has started restructuring proceedings by filing a Notice of Intention (NOI) to Make a Proposal pursuant to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (Canada). In the same release, the company said that, as of March 1, 2024, The Body Shop US Limited has ceased operations," Chain Store Age reported.

A message on the company's U.S. website shared a simple message that does not appear to be the entire story.

"We're currently undergoing planned maintenance, but don't worry we're due to be back online soon."

That same message is still on the company's website, but a new filing makes it clear that the site is not down for maintenance, it's down for good.

The Body Shop files for Chapter 7 bankruptcy

While the future appeared bleak for The Body Shop, fans of the brand held out hope that a savior would step in. That's not going to be the case.

The Body Shop filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in the United States.

"The US arm of the ethical cosmetics group has ceased trading at its 50 outlets. On Saturday (March 9), it filed for Chapter 7 insolvency, under which assets are sold off to clear debts, putting about 400 jobs at risk including those in a distribution center that still holds millions of dollars worth of stock," The Guardian reported.

After its closure in the United States, the survival of the brand remains very much in doubt. About half of the chain's stores in the United Kingdom remain open along with its Australian stores.

The future of those stores remains very much in doubt and the chain has shared that it needs new funding in order for them to continue operating.

The Body Shop did not respond to a request for comment from TheStreet.

bankruptcy pandemic canada-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex