Uncategorized

The Power of Proximity: How Working beside Colleagues Affects Training and Productivity

Firms remain divided about the value of the office for “office” workers. Some firms think that their employees are more productive when working from…

Firms remain divided about the value of the office for “office” workers. Some firms think that their employees are more productive when working from home. Others believe that the office is a key place for investing in workers’ skills. In this post, which is based on a recent working paper, we examine whether both sides could be right: Could working in the office facilitate investments in workers’ skills for tomorrow that diminish productivity today?

We examine the impact of proximity to coworkers on workers’ productivity and mentorship in the context of software engineers at a Fortune 500 firm. The firm shared data with us on the number of programs engineers write and the text of the feedback they receive on their computer code. As is industry standard, software engineers review one another’s code online prior to deployment. This peer review process not only aids in identifying bugs but also helps teach engineers how to write better code in the future. Thus, this feedback gives us a concrete measure of mentorship.

At the firm, engineers varied in their proximity to one another even before COVID-19. The firm has two buildings on its main engineering campus, several blocks apart. Prior to COVID-19, some teams were assigned desks all in one building, while others spanned the buildings. Desk positions alter team dynamics. When the offices were open, engineers on one-building teams held daily stand-up meetings in person. For engineers on multi-building teams, these meetings usually occurred online. As a result, these teams operated more like remote teams even when the offices were open. To identify the causal effects of proximity, we compare the differences between one- and multi-building teams when the offices were open and the differential changes when the offices were closed.

Effects of Proximity on Mentorship

We find that proximity increases mentorship. While offices were open, engineers on one-building teams received 22 percent more comments on their code than did engineers on multi-building teams, as shown in the left side of the chart below. Once the offices closed and everyone worked remotely, the gap largely disappeared, as seen in the right side of the chart. This feedback reflects mentorship: sitting near teammates primarily affects feedback received by junior engineers and given by engineers who have been at the firm longer.

Engineers Working Together Received More Feedback Than Those on Multi-Building Teams

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from a Fortune 500 firm covering the period from August 2019 to December 2020.

Notes: The chart shows the online feedback received by engineers on one-building teams and multi-building teams around the COVID-19 office closures (dashed vertical line). Figures reflect raw averages.

Engineers sitting near teammates receive more feedback partly because they ask more follow-up questions. These additional questions and clarifications highlight how face-to-face interaction complements—rather than substitutes for—online communication. Indeed, our analysis of online feedback likely delivers a lower bound on proximity’s total effect on mentorship insofar as physically sitting together also facilitates face-to-face conversation.

We find that having even one distant teammate dampens mentorship between teammates sitting together. These externalities can explain about a third of proximity’s impact. Furthermore, pre-pandemic, when a new teammate was assigned a desk in another building—flipping a one-building team to a multi-building team—feedback among same-building teammates (who predated the new hire) declined, as shown by the red line in the chart below. By contrast, new hires in the same building had no such impact, as shown by the blue line. Accommodating distant teammates by, for example, moving in-person meetings online, has substantial negative effects on even proximate teammates.

Assigning New Hire to Different Building Decreased Feedback among Workers Who Sat Together

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from a Fortune 500 firm covering the period from August 2019 to December 2020.

Notes: The chart shows the impact of a new hire that converts the team from a one-building team to a multi-building team versus a new hire that does not change the distribution of the team, focusing on the pre-existing relationships between teammates in the same building.

Effects of Proximity on Output, Pay, and Quits

We find, however, that mentorship isn’t free: instead, proximity to coworkers decreases output. Engineers on one-building teams wrote fewer programs than those on multi-building teams while the offices were open, and this differential narrowed once the offices closed. Our estimate suggests that proximity reduces programs written per month by 23 percent. The effects on output are present for both junior and senior engineers but are particularly pronounced for senior engineers, who provide most of the mentoring.

Proximity also affects workers’ career outcomes. Junior workers on one-building teams—who are more focused on building their skills and thus produce less output—were 5 percentage points less likely to receive a pay raise. However, once the offices shut down and mentorship equalized across teams, formerly one-building engineers benefited from the mentorship that they received: they were 7 percentage points more likely to receive a pay raise.

Quits also reflect the impact of proximity. Before COVID-19, quits were relatively rare at this firm. However, with the rise of remote work, quits increased as it became easier to switch to higher-paying Silicon Valley tech firms without relocating from this firm’s East Coast city. Notably, workers who had been trained on one-building teams saw a 1.2 percentage point greater increase in quits, about twice that of engineers trained on multi-building teams. Engineers on one-building teams were more likely to move to roles at firms that offer higher salaries (according to Glassdoor). These results are consistent with the greater training on one-building teams giving engineers the skills they need to secure higher-paying jobs elsewhere. As with pay raises, the effects are larger for women. We do not see the same impacts on firings; while the impacts are not statistically significant, they suggest that workers on one-building teams are less likely to be fired once the offices close.

Who Works in the Office?

Finally, we examine who works at the office versus who works from home. Pre-pandemic, workers’ locations were consistent with the firm placing a high priority on training. Those most involved in mentorship were most likely to be office-based: this was true both for the junior workers receiving the most mentorship and for the senior workers and managers giving the most mentorship. This aligns with national trends in 2022-23, where young workers and older workers are the most likely to have returned to the office, even among those who do not have children. Moreover, when proximity was impossible during the pandemic, the firm moved away from hiring very junior engineers toward hiring workers with more training. While this change could be influenced by many factors, it is consistent with the idea that when the firm faces challenges in facilitating proximity, it decides to “buy” talent instead of “build” it.

Together, these results suggest that there may be a “now versus later” tradeoff when considering the location of work. Working from home may yield short-term gains in output, but this productivity may come at the cost of workers’ long-run skill development. It will be important to analyze whether hybrid work can offer the best of both worlds or whether a tradeoff will remain between short-run output and long-run development.

Natalia Emanuel is a research economist in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Emma Harrington is an assistant professor at the University of Virginia.

Amanda Pallais is a professor of economics at Harvard University.

How to cite this post:

Natalia Emanuel, Emma Harrington, and Amanda Pallais, “The Power of Proximity: How Working beside Colleagues Affects Training and Productivity,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 18, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/01/the-power-of-proximity-how-working-beside-colleagues-affects-training-and-productivity/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Uncategorized

NY Fed Finds Medium, Long-Term Inflation Expectations Jump Amid Surge In Stock Market Optimism

NY Fed Finds Medium, Long-Term Inflation Expectations Jump Amid Surge In Stock Market Optimism

One month after the inflation outlook tracked…

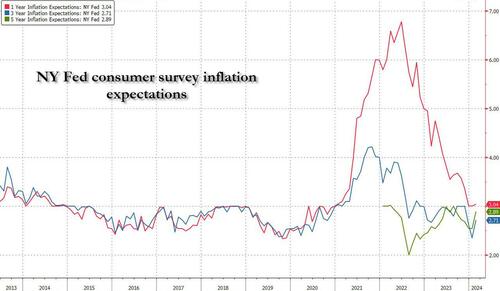

One month after the inflation outlook tracked by the NY Fed Consumer Survey extended their late 2023 slide, with 3Y inflation expectations in January sliding to a record low 2.4% (from 2.6% in December), even as 1 and 5Y inflation forecasts remained flat, moments ago the NY Fed reported that in February there was a sharp rebound in longer-term inflation expectations, rising to 2.7% from 2.4% at the three-year ahead horizon, and jumping to 2.9% from 2.5% at the five-year ahead horizon, while the 1Y inflation outlook was flat for the 3rd month in a row, stuck at 3.0%.

The increases in both the three-year ahead and five-year ahead measures were most pronounced for respondents with at most high school degrees (in other words, the "really smart folks" are expecting deflation soon). The survey’s measure of disagreement across respondents (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile of inflation expectations) decreased at all horizons, while the median inflation uncertainty—or the uncertainty expressed regarding future inflation outcomes—declined at the one- and three-year ahead horizons and remained unchanged at the five-year ahead horizon.

Going down the survey, we find that the median year-ahead expected price changes increased by 0.1 percentage point to 4.3% for gas; decreased by 1.8 percentage points to 6.8% for the cost of medical care (its lowest reading since September 2020); decreased by 0.1 percentage point to 5.8% for the cost of a college education; and surprisingly decreased by 0.3 percentage point for rent to 6.1% (its lowest reading since December 2020), and remained flat for food at 4.9%.

We find the rent expectations surprising because it is happening just asking rents are rising across the country.

At the same time as consumers erroneously saw sharply lower rents, median home price growth expectations remained unchanged for the fifth consecutive month at 3.0%.

Turning to the labor market, the survey found that the average perceived likelihood of voluntary and involuntary job separations increased, while the perceived likelihood of finding a job (in the event of a job loss) declined. "The mean probability of leaving one’s job voluntarily in the next 12 months also increased, by 1.8 percentage points to 19.5%."

Mean unemployment expectations - or the mean probability that the U.S. unemployment rate will be higher one year from now - decreased by 1.1 percentage points to 36.1%, the lowest reading since February 2022. Additionally, the median one-year-ahead expected earnings growth was unchanged at 2.8%, remaining slightly below its 12-month trailing average of 2.9%.

Turning to household finance, we find the following:

- The median expected growth in household income remained unchanged at 3.1%. The series has been moving within a narrow range of 2.9% to 3.3% since January 2023, and remains above the February 2020 pre-pandemic level of 2.7%.

- Median household spending growth expectations increased by 0.2 percentage point to 5.2%. The increase was driven by respondents with a high school degree or less.

- Median year-ahead expected growth in government debt increased to 9.3% from 8.9%.

- The mean perceived probability that the average interest rate on saving accounts will be higher in 12 months increased by 0.6 percentage point to 26.1%, remaining below its 12-month trailing average of 30%.

- Perceptions about households’ current financial situations deteriorated somewhat with fewer respondents reporting being better off than a year ago. Year-ahead expectations also deteriorated marginally with a smaller share of respondents expecting to be better off and a slightly larger share of respondents expecting to be worse off a year from now.

- The mean perceived probability that U.S. stock prices will be higher 12 months from now increased by 1.4 percentage point to 38.9%.

- At the same time, perceptions and expectations about credit access turned less optimistic: "Perceptions of credit access compared to a year ago deteriorated with a larger share of respondents reporting tighter conditions and a smaller share reporting looser conditions compared to a year ago."

Also, a smaller percentage of consumers, 11.45% vs 12.14% in prior month, expect to not be able to make minimum debt payment over the next three months

Last, and perhaps most humorous, is the now traditional cognitive dissonance one observes with these polls, because at a time when long-term inflation expectations jumped, which clearly suggests that financial conditions will need to be tightened, the number of respondents expecting higher stock prices one year from today jumped to the highest since November 2021... which incidentally is just when the market topped out during the last cycle before suffering a painful bear market.

Uncategorized

Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more

New Zillow research suggests the spring home shopping season may see a second wave this summer if mortgage rates fall

The post Homes listed for sale in…

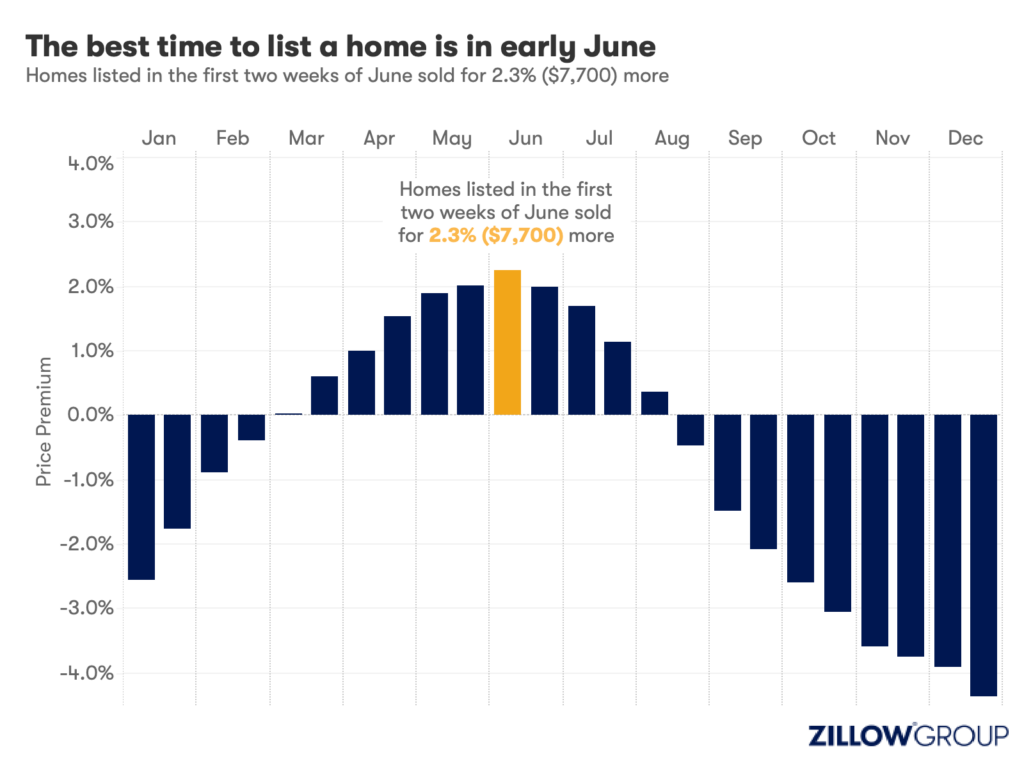

- A Zillow analysis of 2023 home sales finds homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more.

- The best time to list a home for sale is a month later than it was in 2019, likely driven by mortgage rates.

- The best time to list can be as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York and Philadelphia.

Spring home sellers looking to maximize their sale price may want to wait it out and list their home for sale in the first half of June. A new Zillow® analysis of 2023 sales found that homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more, a $7,700 boost on a typical U.S. home.

The best time to list consistently had been early May in the years leading up to the pandemic. The shift to June suggests mortgage rates are strongly influencing demand on top of the usual seasonality that brings buyers to the market in the spring. This home-shopping season is poised to follow a similar pattern as that in 2023, with the potential for a second wave if the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates midyear or later.

The 2.3% sale price premium registered last June followed the first spring in more than 15 years with mortgage rates over 6% on a 30-year fixed-rate loan. The high rates put home buyers on the back foot, and as rates continued upward through May, they were still reassessing and less likely to bid boldly. In June, however, rates pulled back a little from 6.79% to 6.67%, which likely presented an opportunity for determined buyers heading into summer. More buyers understood their market position and could afford to transact, boosting competition and sale prices.

The old logic was that sellers could earn a premium by listing in late spring, when search activity hit its peak. Now, with persistently low inventory, mortgage rate fluctuations make their own seasonality. First-time home buyers who are on the edge of qualifying for a home loan may dip in and out of the market, depending on what’s happening with rates. It is almost certain the Federal Reserve will push back any interest-rate cuts to mid-2024 at the earliest. If mortgage rates follow, that could bring another surge of buyers later this year.

Mortgage rates have been impacting affordability and sale prices since they began rising rapidly two years ago. In 2022, sellers nationwide saw the highest sale premium when they listed their home in late March, right before rates barreled past 5% and continued climbing.

Zillow’s research finds the best time to list can vary widely by metropolitan area. In 2023, it was as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York. Thirty of the top 35 largest metro areas saw for-sale listings command the highest sale prices between May and early July last year.

Zillow also found a wide range in the sale price premiums associated with homes listed during those peak periods. At the hottest time of the year in San Jose, homes sold for 5.5% more, a $88,000 boost on a typical home. Meanwhile, homes in San Antonio sold for 1.9% more during that same time period.

| Metropolitan Area | Best Time to List | Price Premium | Dollar Boost |

| United States | First half of June | 2.3% | $7,700 |

| New York, NY | First half of July | 2.4% | $15,500 |

| Los Angeles, CA | First half of May | 4.1% | $39,300 |

| Chicago, IL | First half of June | 2.8% | $8,800 |

| Dallas, TX | First half of June | 2.5% | $9,200 |

| Houston, TX | Second half of April | 2.0% | $6,200 |

| Washington, DC | Second half of June | 2.2% | $12,700 |

| Philadelphia, PA | First half of July | 2.4% | $8,200 |

| Miami, FL | First half of June | 2.3% | $12,900 |

| Atlanta, GA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $8,700 |

| Boston, MA | Second half of May | 3.5% | $23,600 |

| Phoenix, AZ | First half of June | 3.2% | $14,700 |

| San Francisco, CA | Second half of February | 4.2% | $50,300 |

| Riverside, CA | First half of May | 2.7% | $15,600 |

| Detroit, MI | First half of July | 3.3% | $7,900 |

| Seattle, WA | First half of June | 4.3% | $31,500 |

| Minneapolis, MN | Second half of May | 3.7% | $13,400 |

| San Diego, CA | Second half of April | 3.1% | $29,600 |

| Tampa, FL | Second half of June | 2.1% | $8,000 |

| Denver, CO | Second half of May | 2.9% | $16,900 |

| Baltimore, MD | First half of July | 2.2% | $8,200 |

| St. Louis, MO | First half of June | 2.9% | $7,000 |

| Orlando, FL | First half of June | 2.2% | $8,700 |

| Charlotte, NC | Second half of May | 3.0% | $11,000 |

| San Antonio, TX | First half of June | 1.9% | $5,400 |

| Portland, OR | Second half of April | 2.6% | $14,300 |

| Sacramento, CA | First half of June | 3.2% | $17,900 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $4,700 |

| Cincinnati, OH | Second half of April | 2.7% | $7,500 |

| Austin, TX | Second half of May | 2.8% | $12,600 |

| Las Vegas, NV | First half of June | 3.4% | $14,600 |

| Kansas City, MO | Second half of May | 2.5% | $7,300 |

| Columbus, OH | Second half of June | 3.3% | $10,400 |

| Indianapolis, IN | First half of July | 3.0% | $8,100 |

| Cleveland, OH | First half of July | 3.4% | $7,400 |

| San Jose, CA | First half of June | 5.5% | $88,400 |

The post Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more appeared first on Zillow Research.

federal reserve pandemic home sales mortgage rates interest ratesUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

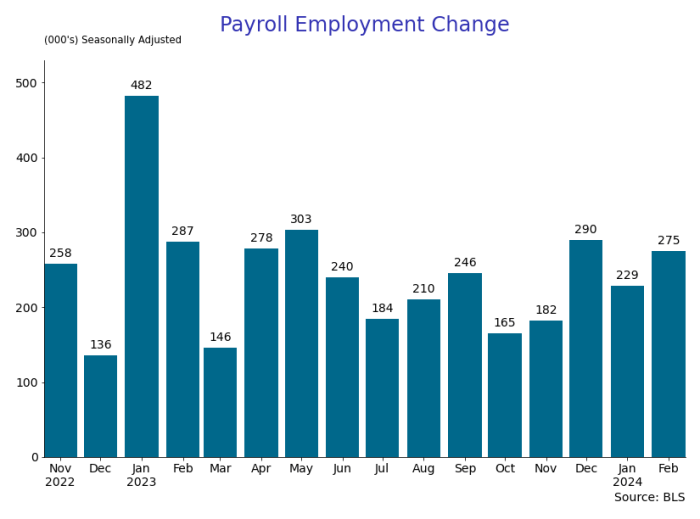

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemployment-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex