The Future For Value Investing

During his recent interview with Tobias, Andrew Wellington, Co-Founder and Managing Partner at Lyrical Asset Management discussed The Future For Value Investing. Here’s an excerpt from the interview: Q3 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more…

During his recent interview with Tobias, Andrew Wellington, Co-Founder and Managing Partner at Lyrical Asset Management discussed The Future For Value Investing. Here’s an excerpt from the interview:

Q3 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

The Future For Value Investing

Tobias: You’re a deep-value guy in the mid-cap space. It’s been a mixed bag for deep value and for value in the States in particular. The first decade of the 2000s was absolutely spectacular for value. The last decade has been quite tough. I think probably value and quality would have done quite well through to say 2018. The very beginning of 2018, and then it’s been a long grind lower since then. Do you have any view on what it would take for value to turn around or if value turned around already?

Andrew: Let me correct you on one thing. We’re not a mid-cap manager. I would describe us as a large-cap manager. I did run mid-cap at Neuberger, but our investment universe is the 1000 largest US stocks. So, I would say that is the large-cap and mid-cap universe. What will it take for a value to turn around? Right now, it looks like what it takes for value to turn around is the calendar to flip from March 18 to March 19. Right now, that looks like the bottom. You have the correct timing about value. If you looked at the value indices, it looks like they haven’t worked for 14 years, but if you look at what we think are better measures of value, like how did the lowest PE stocks perform, they outperform by quite a large margin from 09 through 17. Value is only been underperforming for about two years, 18, 19, and then a pretty nasty downturn in February, March of this year as the pandemic erupted.

Then, they bottomed on March 18. By our calculation, the lowest PE stocks in the US are up over 80% since March 18, that’s almost 30 percentage points better than the S&P 500. They’re in a big hole, so they haven’t completely dug their way out, but going up 80% in nine months is a good start. To my point earlier about the value indices, while the lowest PE stocks are up 80% and have outperformed by almost 30 percentage points, the large-cap value indices have underperformed the S&P. This isn’t new. The large-cap value indices underperformed the S&P over those nine years from 09 through 17, when the lowest PE stocks outperformed. Those indices aren’t great at capturing what value really is. It’s a shame because it’s turned a lot of allocators off of investing in value stocks, thinking it’s broken when it’s the indices that are broken, not value investing.

We did have this really tough period from 18 and 19. The tech bubble was worse for me. That’s the vantage of experience I’ve lived– this is now the third period, where values underperform that I’ve lived through. The first being the tech bubble and the second being the financial crisis, and compared to those two, this was a piece of cake. The tech bubble was more severe in terms of growth outperforming value. The financial crisis was just scary for everything. I was starting to think, what am I going to do for a living because I can’t be an investor in the stock market, that’s going away. Those are much scarier times than this.

Also, by far of this period, the worst performance was in 2018 for value. It was actually the best year for company earnings in Lyrical’s 12 year history. It was difficult to put up with the market action, but there really wasn’t much doubt that we own the right companies. Our companies were growing, they were growing faster than the S&P 500, just when their earnings went up, their multiples went down, and the stocks underperform. They weren’t facing any existential threats. It was easy to know as an analyst, you had gotten the right stocks right. It was just very trying for the business as clients grew frustrated with performance and things like that, to deal with that side of it

Tobias: Do you have any thoughts on what caused it?

Andrew: Caused the downturn?

Tobias: Just that little air pocket that value saw 2018, 2019, and a little bit of this year?

Andrew: Yeah. No idea at all. I’ve been thinking about this for 25 years, and I’m still no closer to finding why does value go through cycles? It is a mystery. It always seems to be. I think it’s a two-step process, I think. There’s the initial thing that happens, that gets value to underperform for a bit of time. That’s different every time. It could be economic fear, it could be falling in love with the internet for the first time. Something gets value to underperform enough that the second thing happens, which is the positive feedback loop of momentum. It’s a different trigger every time, which is why it’s hard to find a systematic cause, but something pushes value to the certain point where people start to give up on it. And that causes it to underperform some more, which causes more people. So, it’s a compound effect.

Something gets the ball rolling, so you got this boulder perched at the top of a hill. What gets it rolling is different than what keeps it rolling. What keeps it rolling is gravity or momentum, but what gets it rolling is just a really strong wind or just a slight little tremor, just something seems to happen. It’s not regular enough that you could actually trade around it, but if you go back and you study the performance of low value stocks, this happens about two years every 10 years. You got eight years of outperformance, in two years of underperformance. Sometimes it’s 12 and 1, sometimes it’s 7 and 2.

If you zoom out, we see this recurring pattern over the last 60 years that you get value outperformance for a while and then you get two years of retrenchment, and then it outperforms, and it’s okay because if you just held– the good years and the bad years all put together, you still end up with close to 500 basis points of outperformance over a full cycle. The down cycles tend to be more acute. The annualized returns are more negative then, but it’s just two years. And then you get very good positive returns over eight years. Eight years of compounding overwhelms those two bad years, but two years is enough to shake some people loose. That’s the challenging part of value investing. I don’t know why it goes through these cycles, but it clearly does.

Tobias: One of the things that I’ve observed, and I don’t know, it’s not necessarily quantifiable, but I think that value tends to sell off first. I think that in 2007, that was certainly true that I think value started dipping first. I think it’s longer bow, but I do think the late 1990s was value selling off.

Then there was a very big sell-off for the market and for the tech stocks, where value is doing quite well through that period, value just being long-only, you could be going up while the rest of the market was going down. I don’t know that we’ve seen the end of the cycle yet. Or maybe we have, but I thought that we’d seen– I think we’d seen a couple of years of sell-off before the market kind of woke up. I just wonder if it’s value investors being a little bit more disciplined about what they prepared to pay in the sense that they just the bid goes away for value when the market gets very frothy, so value starts retrenching.

Andrew: I think that might be right for one cycle. When you go back and look at these cycles, it’s always a different set of circumstances. It’s really hard to come up with one reason. You might be able to figure out what caused it this time. Although this time is the hardest one for me to figure out. I know value underperformed in 07 and 08, I know what to label that, that was a global financial crisis. Value underperformed in 98, 99, and I know what to label that, that was the tech bubble. I don’t know what label to put on this.

What happened in 18 that was different than 17. I still don’t know. I mean, you have the FAANGs, but this was way bigger than just the FAANGs. You take the FAANGs out of the market and you still saw it happen. I’m not really sure what was behind it this time. I don’t know what label to put on it. This one’s still a head-scratcher. Maybe it’ll be clearer in hindsight, but I doubt that too. We’re never going to know more about– we’re not going to remember 2018. It just really came out of the blue.

November, Thanksgiving 2017, we’re ahead of the market again. We get into 18, and low PE stocks underperform almost every single month of 2018. I think it was like 10 out of 12 months, they underperformed. It was just brutal. Our companies were beating earnings. Then, we had the best year. The highest percentage of the portfolio outperformed earnings expectations that year, is just one simple metric. In every other year companies in our portfolio that beat earnings, on average outperform by, something like 1000 basis points. That subset of the portfolio. Unfortunately, it’s never 100% of the portfolio. In that year, they underperformed the first time in our 12-year history.

Tobias: And so, they beat, and then underperform the market.

Andrew: Yeah, we disaggregated it. There’s a something in psychology called a feature positive effect, it’s hard to see what isn’t there. When you have a bad year, everyone wants to blame it on, “Oh, well, look at these bad stocks you own.” I say, “Yeah, but look at 2009, we had a great year, and look at all these bad stocks we own. We have bad stocks every year. We outperform most of those years.”

So, it’s not the bad stocks. What do we have compared to normal, and what we noticed was, we had a normal number of bad stocks, and they did a little worse than normal bad, but what really hurt our returns in 2018 was, we had an abnormally large number of good stocks from an earnings point of view. They did abnormally bad. It wasn’t the losers in a way that hurt us. It was the total absence of stock winners, even though they were earnings winners. I still can’t explain why that– I can tell you very precisely exactly how much that happened in the numbers behind what did happen, but the why is still a great mystery.

Tobias: In one of AQRs papers were the guys who would look at value investing, it’s not Cliff Asness, but some of his colleagues had looked at this and they just they create this system to test the relationship between fundamentals and performance. The way that they do it is they give it forward earnings a year in advance. It’s explicitly cheating to do this. Then they look at the performance, and if you get those results, you get a spectacular Sharpe and sorting out for the entire period, but there are two notable periods where it doesn’t work, and if anything, the sign is the around the other way. It was 98, 99, and it’s been 2019 and 2020 have been– the relationship is just not– it’s a negative relationship. So, the closer you’re tied to fundamentals, the worst you do.

Andrew: Yeah, I mean, that certainly is what it felt like. Wes Gray did a great paper a few years ago, I think he called it like the God Portfolio, or even God would get fired as a hedge manager, where he actually looked forward and said, “Who had the best earnings growth over the next five years? Let’s own those five years early, and even they had huge years of underperformance. The aggregate returns were insane.

He even pointed out that you couldn’t– even if you were God, you couldn’t invest in this strategy, because you’d fall out at such a high rate, you’d be bigger than the entire stock market. It was a great exercise to just so show that if you were perfect, you owned the 10 best earnings grow, even then you had bad years in that. I guess you could say quite provably the market does get it wrong from time to time.

You can find out more about Tobias’ podcast here – The Acquirers Podcast. You can also listen to the podcast on your favorite podcast platforms here:

- Apple Podcasts

- Breaker

- PodBean

- Overcast

- Youtube

- Pocket Casts

- RadioPublic

- Anchor

- Spotify

- Stitcher

- Google Podcasts

For more articles like this, check out our value investing news here.

The post The Future For Value Investing appeared first on ValueWalk.

sp 500 stocks pandemicUncategorized

Industrial Production Increased 0.1% in February

From the Fed: Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization

Industrial production edged up 0.1 percent in February after declining 0.5 percent in January. In February, the output of manufacturing rose 0.8 percent and the index for mining climbed 2.2 p…

Industrial production edged up 0.1 percent in February after declining 0.5 percent in January. In February, the output of manufacturing rose 0.8 percent and the index for mining climbed 2.2 percent. Both gains partly reflected recoveries from weather-related declines in January. The index for utilities fell 7.5 percent in February because of warmer-than-typical temperatures. At 102.3 percent of its 2017 average, total industrial production in February was 0.2 percent below its year-earlier level. Capacity utilization for the industrial sector remained at 78.3 percent in February, a rate that is 1.3 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2023) average.

emphasis added

Click on graph for larger image.

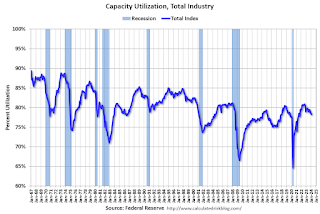

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows Capacity Utilization. This series is up from the record low set in April 2020, and above the level in February 2020 (pre-pandemic).

Capacity utilization at 78.3% is 1.3% below the average from 1972 to 2022. This was below consensus expectations.

Note: y-axis doesn't start at zero to better show the change.

The second graph shows industrial production since 1967.

The second graph shows industrial production since 1967.Industrial production increased to 102.3. This is above the pre-pandemic level.

Industrial production was above consensus expectations.

International

Fuel poverty in England is probably 2.5 times higher than government statistics show

The top 40% most energy efficient homes aren’t counted as being in fuel poverty, no matter what their bills or income are.

The cap set on how much UK energy suppliers can charge for domestic gas and electricity is set to fall by 15% from April 1 2024. Despite this, prices remain shockingly high. The average household energy bill in 2023 was £2,592 a year, dwarfing the pre-pandemic average of £1,308 in 2019.

The term “fuel poverty” refers to a household’s ability to afford the energy required to maintain adequate warmth and the use of other essential appliances. Quite how it is measured varies from country to country. In England, the government uses what is known as the low income low energy efficiency (Lilee) indicator.

Since energy costs started rising sharply in 2021, UK households’ spending powers have plummeted. It would be reasonable to assume that these increasingly hostile economic conditions have caused fuel poverty rates to rise.

However, according to the Lilee fuel poverty metric, in England there have only been modest changes in fuel poverty incidence year on year. In fact, government statistics show a slight decrease in the nationwide rate, from 13.2% in 2020 to 13.0% in 2023.

Our recent study suggests that these figures are incorrect. We estimate the rate of fuel poverty in England to be around 2.5 times higher than what the government’s statistics show, because the criteria underpinning the Lilee estimation process leaves out a large number of financially vulnerable households which, in reality, are unable to afford and maintain adequate warmth.

Energy security

In 2022, we undertook an in-depth analysis of Lilee fuel poverty in Greater London. First, we combined fuel poverty, housing and employment data to provide an estimate of vulnerable homes which are omitted from Lilee statistics.

We also surveyed 2,886 residents of Greater London about their experiences of fuel poverty during the winter of 2022. We wanted to gauge energy security, which refers to a type of self-reported fuel poverty. Both parts of the study aimed to demonstrate the potential flaws of the Lilee definition.

Introduced in 2019, the Lilee metric considers a household to be “fuel poor” if it meets two criteria. First, after accounting for energy expenses, its income must fall below the poverty line (which is 60% of median income).

Second, the property must have an energy performance certificate (EPC) rating of D–G (the lowest four ratings). The government’s apparent logic for the Lilee metric is to quicken the net-zero transition of the housing sector.

In Sustainable Warmth, the policy paper that defined the Lilee approach, the government says that EPC A–C-rated homes “will not significantly benefit from energy-efficiency measures”. Hence, the focus on fuel poverty in D–G-rated properties.

Generally speaking, EPC A–C-rated homes (those with the highest three ratings) are considered energy efficient, while D–G-rated homes are deemed inefficient. The problem with how Lilee fuel poverty is measured is that the process assumes that EPC A–C-rated homes are too “energy efficient” to be considered fuel poor: the main focus of the fuel poverty assessment is a characteristic of the property, not the occupant’s financial situation.

In other words, by this metric, anyone living in an energy-efficient home cannot be considered to be in fuel poverty, no matter their financial situation. There is an obvious flaw here.

Around 40% of homes in England have an EPC rating of A–C. According to the Lilee definition, none of these homes can or ever will be classed as fuel poor. Even though energy prices are going through the roof, a single-parent household with dependent children whose only income is universal credit (or some other form of benefits) will still not be considered to be living in fuel poverty if their home is rated A-C.

The lack of protection afforded to these households against an extremely volatile energy market is highly concerning.

In our study, we estimate that 4.4% of London’s homes are rated A-C and also financially vulnerable. That is around 171,091 households, which are currently omitted by the Lilee metric but remain highly likely to be unable to afford adequate energy.

In most other European nations, what is known as the 10% indicator is used to gauge fuel poverty. This metric, which was also used in England from the 1990s until the mid 2010s, considers a home to be fuel poor if more than 10% of income is spent on energy. Here, the main focus of the fuel poverty assessment is the occupant’s financial situation, not the property.

Were such alternative fuel poverty metrics to be employed, a significant portion of those 171,091 households in London would almost certainly qualify as fuel poor.

This is confirmed by the findings of our survey. Our data shows that 28.2% of the 2,886 people who responded were “energy insecure”. This includes being unable to afford energy, making involuntary spending trade-offs between food and energy, and falling behind on energy payments.

Worryingly, we found that the rate of energy insecurity in the survey sample is around 2.5 times higher than the official rate of fuel poverty in London (11.5%), as assessed according to the Lilee metric.

It is likely that this figure can be extrapolated for the rest of England. If anything, energy insecurity may be even higher in other regions, given that Londoners tend to have higher-than-average household income.

The UK government is wrongly omitting hundreds of thousands of English households from fuel poverty statistics. Without a more accurate measure, vulnerable households will continue to be overlooked and not get the assistance they desperately need to stay warm.

Torran Semple receives funding from Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) grant EP/S023305/1.

John Harvey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

european uk pandemicUncategorized

Southwest and United Airlines have bad news for passengers

Both airlines are facing the same problem, one that could lead to higher airfares and fewer flight options.

Airlines operate in a market that's dictated by supply and demand: If more people want to fly a specific route than there are available seats, then tickets on those flights cost more.

That makes scheduling and predicting demand a huge part of maximizing revenue for airlines. There are, however, numerous factors that go into how airlines decide which flights to put on the schedule.

Related: Major airline faces Chapter 11 bankruptcy concerns

Every airport has only a certain number of gates, flight slots and runway capacity, limiting carriers' flexibility. That's why during times of high demand — like flights to Las Vegas during Super Bowl week — do not usually translate to airlines sending more planes to and from that destination.

Airlines generally do try to add capacity every year. That's become challenging as Boeing has struggled to keep up with demand for new airplanes. If you can't add airplanes, you can't grow your business. That's caused problems for the entire industry.

Every airline retires planes each year. In general, those get replaced by newer, better models that offer more efficiency and, in most cases, better passenger amenities.

If an airline can't get the planes it had hoped to add to its fleet in a given year, it can face capacity problems. And it's a problem that both Southwest Airlines (LUV) and United Airlines have addressed in a way that's inevitable but bad for passengers.

Image source: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Southwest slows down its pilot hiring

In 2023, Southwest made a huge push to hire pilots. The airline lost thousands of pilots to retirement during the covid pandemic and it needed to replace them in order to build back to its 2019 capacity.

The airline successfully did that but will not continue that trend in 2024.

"Southwest plans to hire approximately 350 pilots this year, and no new-hire classes are scheduled after this month," Travel Weekly reported. "Last year, Southwest hired 1,916 pilots, according to pilot recruitment advisory firm Future & Active Pilot Advisors. The airline hired 1,140 pilots in 2022."

The slowdown in hiring directly relates to the airline expecting to grow capacity only in the low-single-digits percent in 2024.

"Moving into 2024, there is continued uncertainty around the timing of expected Boeing deliveries and the certification of the Max 7 aircraft. Our fleet plans remain nimble and currently differs from our contractual order book with Boeing," Southwest Airlines Chief Financial Officer Tammy Romo said during the airline's fourth-quarter-earnings call.

"We are planning for 79 aircraft deliveries this year and expect to retire roughly 45 700 and 4 800, resulting in a net expected increase of 30 aircraft this year."

That's very modest growth, which should not be enough of an increase in capacity to lower prices in any significant way.

United Airlines pauses pilot hiring

Boeing's (BA) struggles have had wide impact across the industry. United Airlines has also said it was going to pause hiring new pilots through the end of May.

United (UAL) Fight Operations Vice President Marc Champion explained the situation in a memo to the airline's staff.

"As you know, United has hundreds of new planes on order, and while we remain on path to be the fastest-growing airline in the industry, we just won't grow as fast as we thought we would in 2024 due to continued delays at Boeing," he said.

"For example, we had contractual deliveries for 80 Max 10s this year alone, but those aircraft aren't even certified yet, and it's impossible to know when they will arrive."

That's another blow to consumers hoping that multiple major carriers would grow capacity, putting pressure on fares. Until Boeing can get back on track, it's unlikely that competition between the large airlines will lead to lower fares.

In fact, it's possible that consumer demand will grow more than airline capacity which could push prices higher.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

bankruptcy pandemic stocks-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International1 week ago

International1 week agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International7 days ago

International7 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Spread & Containment2 days ago

Spread & Containment2 days agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex