International

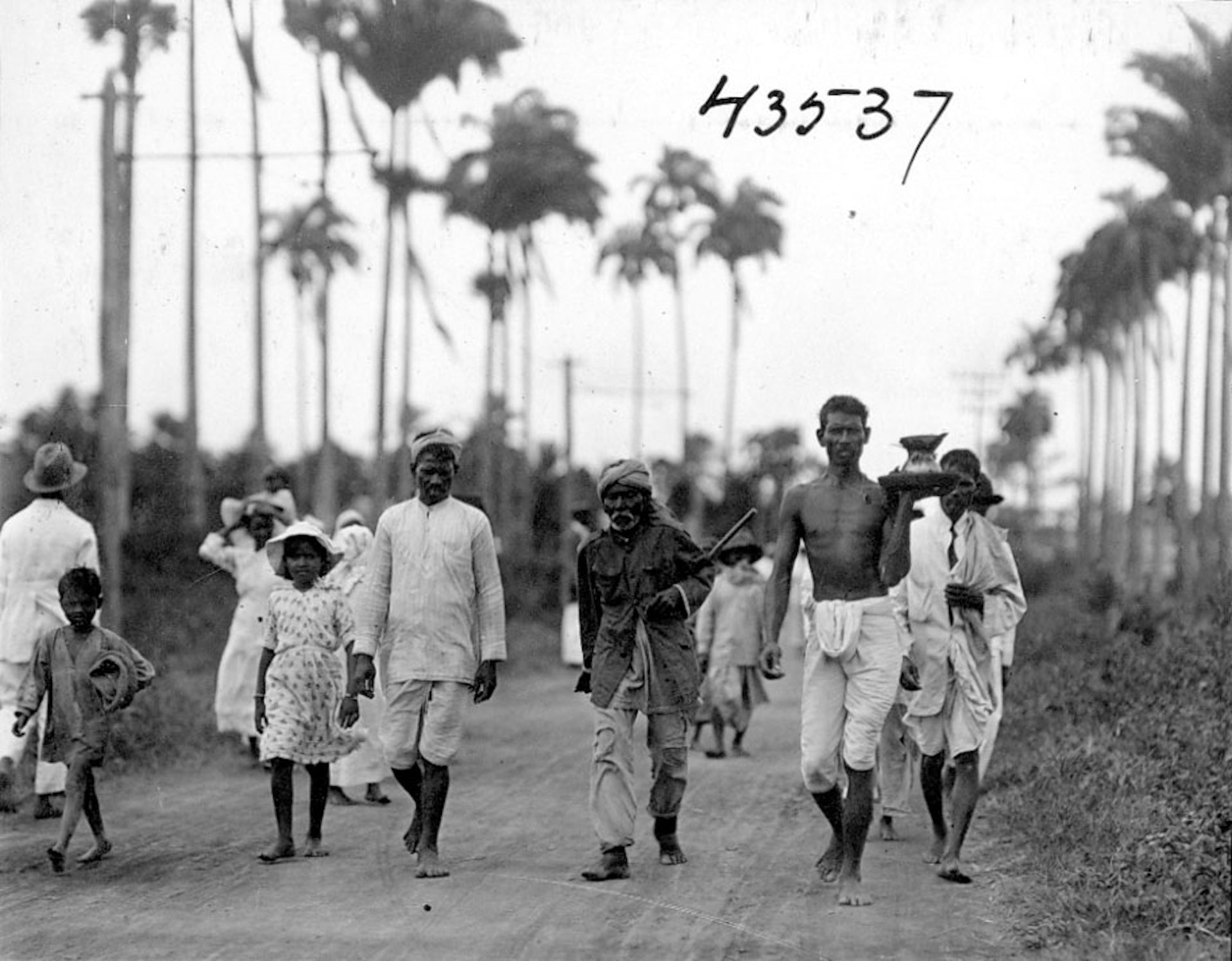

Invisible Windrush: how the stories of Indian indentured labourers from the Caribbean were forgotten

When people think about the Windrush generation, they are unlikely to imagine someone like my father, who was not black but a person of Indian-Caribbean…

My father never spoke to us about Guyana, the country of his birth, when we were growing up because he believed that his history had no value to his children. In doing this, he was unconsciously copying his grandparents, as well as others in his community, who had collectively chosen not to talk about their past.

Sadly, in our case, this familial silence was like a bullet that ricocheted down the generations. It was fired in 1886 when my 22-year-old great-grandfather was recruited from India as an indentured labourer to travel to British Guiana (the spelling changed to Guyana in 1966 after independence) on a ship called the Foyle. It went on to the vessel that carried my father to Britain from Guyana in 1961, before taking aim at my brothers and I – a group of disaffected and confused children who had no real understanding of what our cultural heritage was.

When my father, Surujpaul Kaladeen, left Guyana, aged 23, he joined half a million other people from the Caribbean who made the journey to a new life in the UK between 1948 and 1971. This group of people became known as the Windrush generation.

When people think about the Windrush generation the images they tend to associate with this period are the black and white photos taken of African-Caribbean people at Tilbury Docks or Waterloo train station.

They are unlikely to imagine someone like my father, who was not black but a person of Indian-Caribbean heritage. It took me many years to unpick my family history and to understand that we were not the only ones to experience this kind of cultural amnesia growing up.

When my son was born in 2013, I began to understand myself in the context of being an “invisible passenger in two imperial migrations”. Because, not only was the system of indenture generally unknown to the wider public, but as a consequence, the presence of Indian people in the Caribbean was also unknown. So, we were never recognised as part of the Windrush generation.

The fact that we did not look like we were part of a discernible community and that we were constantly faced with questions about our origins, was difficult for us growing up. I believe it was a contributory factor to the tragic outcomes that followed for my brothers.

The system of indenture was started in Mauritius in 1834 so that the British could cheaply replace enslaved Africans following the abolition of slavery in the British empire.

Under the British empire over two million people of Indian heritage were transported, through the indenture system, to countries on five different continents. While you will encounter British people of Indian-Mauritian, Indian-South African and Indian-Fijian heritage in the UK, the system of indenture that brought their ancestors to those countries is entirely absent from school curriculums and until recently, university syllabuses too.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

But what has also helped Britain “forget” the creation and maintenance of the system of indenture across the 19th and early 20th centuries is the community’s own attitude to its past. Many of my great-grandparent’s generation connected their poverty and their departure from India – with its associated rupture of family ties – to feelings of shame.

Caribbean heritage, but not black

In some ways, I now look at my life as an academic as one long love letter to my older brothers. I wanted to understand the role that the absence of knowing our father’s history had played in shaping us as children, before we ever really had a chance to form questions about who we were.

I have dedicated my academic career to an exploration of the history and literature of indenture and my book, The Other Windrush, edited with the academic and author David Dabydeen, is about the lives of people who grew up like me: descendants of the system of indenture whose history was unknown to the wider world.

In the early 2000s I embarked on archival research for my MA and subsequent PhD on colonial writing on indentured Indians in Guyana, which sits between Venezuela and Suriname, and is the only English-speaking country in South America. Guyana is part of the mainland Caribbean region.

I was convinced that in understanding the series of events that had led my ancestors from India to the Caribbean in the 19th century, I would in turn be able to work out what had happened to my brothers: gifted, bright, and beautiful boys who had stumbled catastrophically into adulthood.

Whether expressed through prison sentences, addiction or homelessness, their existence seemed to be a rejection of anything that resembled a normal life.

We were of Caribbean heritage, but not black. We were further of mixed heritage as our mum was white, but nobody used these labels in those days and to the world outside we were simply “pakis” – the word British racists used as a pejorative slur for anyone of South Asian heritage.

What I did not understand then, and what I have come to understand only recently, is that any comprehension of the role that indenture played in our lives was incomplete without understanding my father’s journey from the Caribbean to the UK as part of the Windrush generation.

What was indenture?

Indians were taken from India to work on colonial sugar, rubber, tea and cocoa plantations in the 19th and early 20th century. By the time indenture was abolished in 1917, the system had spread from Mauritius and the Caribbean to Fiji, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and beyond.

Considering the enormity of the system of indenture, which transported over two million men, women and children from India to parts of the British empire across the globe, it is surprising that it is so rarely acknowledged in public institutions in the UK. Indeed, the silence that surrounds it perhaps indicates how troubling its presence is in British imperial history as it disrupts the idea of the British empire as an institution that did not profit from exploitative systems of unfree labour after the abolition of slavery.

When indenture was abolished it left an overseas Indian community scattered across the world.

This article is part of our Windrush 75 series, which marks the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain. The stories in this series explore the history and impact of the hundreds of passengers who disembarked to help rebuild after the second world war.

A few facts unite the stories of those Indian communities: most never returned to India, despite their right to a free passage on completion of their indenture and a period of residence in the colony; and they spoke rarely or selectively about the past and what had led them to agree to travel so far.

Undoubtedly, many Indian indentured immigrants were duped into making the journey. It was common, for example, for recruiters to lie about the type of work and the amount of pay involved. But we also know that others made decisions to indenture based on an understanding that it could offer an escape from familial or societal pressures, famine and poverty.

In Guyana and Trinidad, the system itself sought to encourage Indian workers to remain in the country by offering a bounty or a plot of land to those that re-indentured. When considering the power of the plantation economy in individual countries and its ability to encircle workers, it is perhaps unsurprising that people made the decision to stay in their new homes, particularly in cases where they had left challenging family circumstances.

The population of the Caribbean was transformed by the system of indenture and not only from Indian labourers. Chinese indentured labourers arrived in Guyana and Trinidad in 1853 and to Jamaica in 1854. By the time the indenture system had been abolished in 1917, close to 18,000 Chinese and almost 450,000 Indians had been brought to the British Caribbean.

‘Collective amnesia’

I remember a scene in a BBC documentary about indenture, from 2002, called Coolies: How Britain Reinvented Slavery. In that scene my colleague, David Dabydeen, is standing among paper fragments and neglected records in an old post office in Guyana.

Whispering, so that no one will hear him and be offended, he speaks to the camera in his beautiful Berbice-to-Tooting-to-Cambridge drawl: “I believe that people don’t want to remember the past,” he says.

It’s a past of shame it’s not something they want to preserve in the way that in England you would preserve castles or Arthurian legend.

In this he is supported by the Guyanese historian, Clem Seecharan, who frequently refers to a type of “collective amnesia” affecting the first generation of Indian indentured immigrants to the Caribbean, who internalised both the shame of being part of a system that subjugated them and, in many cases, also carried the burden of a complicated past in India.

When I was growing up the term Windrush generation had not yet been coined and work in universities on the idea of “Indian-Caribbean” as an identity and a diaspora, had not yet begun. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why there was no vocabulary to express who we were.

David, the ‘true child of Windrush’

My oldest brother David was born in 1965 and was a true child of Windrush and when I say that I mean it in the sense that he experienced the worst of the prejudice of this period. Born when my parents were living in a rented room that they had struggled to find, he accompanied them on their journey to flat rental and eventual home ownership.

There is a photo of David standing outside our family home around 1974, he is just about smiling I think, and squinting because the sun is in his eyes. To me, he appears to be looking out at an unknown future that perhaps, because of this new house, seems a little brighter than before.

When David died in his early forties in 2008, having lived much of his adult life as a rough sleeper, my father was haunted by the decisions that he had made when we were children, believing that if he had just acted at a particular moment, David’s life could have been completely different.

He focused particularly on an occasion when David was racially attacked at school and another boy had hit him with a cricket bat. The incident had been serious enough to cause his head to bleed badly and my dad lamented that he had not immediately removed him from this school, which was famous in our area for being somewhere you survived rather than attended. Each of us have stories about David like this.

For my mum it was the night that David was stopped by the police and subjected to a humiliating strip search in a police van, despite explaining to the police that his house was 100 metres away and that if they knocked on the door, my mother would happily explain that the bike he was wheeling was not stolen: it was his.

I was a little girl at this time, perhaps only nine or ten years old, but I remember that even my mum, who famously “didn’t get” why we had a problem with racism, was angry. Like a million white women before her she had crossed the colour bar with certain misconceptions intact – the justice and the fairness of the British police was one of them.

Nobody asked us initially to identify his body because in typical David fashion he had always slept with his birth certificate on his person, in a plastic wallet, safe from the elements. My youngest brother, Eddie, who was born in 1973, refused to believe that the body in the hospital mortuary was David’s. As my father and I stood at the edges of the room, Eddie broke free and ran to his brother, touching his face as he repeated his name in disbelief.

Eddie, ‘the centre of my life growing up’

Two years ago, I cradled the scatter tube that held Eddie’s ashes in my arms as my husband drove me to the crematorium where we had left David 13 years before. Found dead in his flat in the middle of the pandemic, he had survived longer than anyone who loved him thought that he might.

In my eyes, his life since adolescence had been a long flirtation with death and each of us had made dashes across London to various hospitals where he had been taken after overdoses or as a result of being sectioned. In my mind, when I enter our childhood house and wander around the rooms looking for pieces of our story, I inevitably find Eddie, who was the centre of my life growing up.

Two years older than me, Eddie was the person in my childhood who I admired most. He was a strong, athletic boy who could draw, programme computers, skateboard like a demon and write incredible stories. I looked up to him enormously and refused to consider any of the accumulating evidence that he was lying to me regularly, right up until the point that a local drug dealer arrived on our doorstep demanding to see him.

Perhaps there is no intimacy like that of a sibling relationship. There are parts of ourselves that are known exclusively to the people who watched us when we were in formation. I am aware that in losing David and Eddie, I have also lost parts of myself; memories that are irretrievable without them.

It is of course impossible to know if my brothers’ lives would have been different if they had a better sense of our father’s history and heritage. But the void we felt as children and the way in which this absence of familial history affected them, motivated my studies.

Who was my father?

As I progressed through my PhD my father, and his siblings who had moved to Canada after his migration to the UK, shared what they knew about their parents and grandparents with me. My father, who was born in 1938, in particular remembered his maternal grandfather, who unlike his paternal grandfather had come from the south of India and with whom he spent every summer growing up. Among the stories about this grandfather that he and his older brother shared with me were those of the Kali Mai Puja, an important religious celebration for South Indians in Guyana.

I understood that much of my father’s reluctance to speak about the past was connected not only to his parents’ and grandparents’ omissions, but also the ideas he had garnered throughout his childhood that his history did not have the same value as that of his colonisers.

The superiority of everything British was an idea that had been absorbed throughout his boyhood in Guyana which remained a colony until 1966. Every aspect of his education was connected to Britain, and he spoke to me often, after he had retired, about a textbook that he remembered with great affection called the Royal Reader. It was in this book that he had encountered one of his favourite poems by Tennyson called The Brook.

In an echo of the silence of our childhood, I discovered, after my mother’s death in 2019, that he had managed to hide an early diagnosis of dementia from both her and us for over four years. In the remaining time we had left, as his illness worsened, he would share a story with me about his daily journey to Peter’s Hall primary school, the school that served the children of the sugar estate of the same name. In this tale he would recall his first teacher and the walk home from school where he would pass his uncles who were working as canecutters on the sugar estate.

He spoke often of his South Indian grandfather, Swantimala, and I remembered a story that his older brother had told me many years before, about how my father had nearly died as a toddler, but that Swantimala had come to the house and asked his daughter, my grandmother, for permission to take care of him during his illness. He returned with him only once he had recovered.

To me this story represented everything that we had lacked growing up in London: the wonder of an extended family and the security of being born into a community of others like you.

I imagined this handsome, dark-skinned, grey-haired man striding off down the road with my dad in his arms and his daughter, looking on, safe in the knowledge that he could make everything right.

I hoped that if my father, who died earlier this year, lost other memories, some trace of this sensation he would have had as a toddler could remain. That he was the beloved grandson of a man who loved his daughter, and a daughter who in turn trusted her father. A child who was in that moment safe in the land of his birth – peaceful and unaware of all that he would one day leave behind.

Any sound is better than silence

I was in the middle of my doctorate when David died in 2008. For over a year I was unable to write or do any research. In the face of his death the recovery of our history seemed a pointless practice that would change nothing for him. I revisited these emotions in 2021 when Eddie died in the build-up to the launch of The Other Windrush.

In the same documentary that features David Dabydeen’s search for his great-grandfather’s indenture records in Guyana, the late Indian-Fijian historian Brij Lal speaks of the dedication of his entire adult life, to the study of indenture. He says he is “haunted” by the “ghosts of the past”. He adds: “It’s very emotional because I am not talking about a group of people in the abstract, I’m talking about people from whom I’m descended.”

I am unable to give these memories of Swantimala and the comforting roots they provide to my brothers. It is of course too late for that.

But in those moments where it has felt nothing can counter the pain of their loss, that this work does not matter, I am reminded that the research itself is an act of resistance and that in advocating for the history of the “ghosts of the past”, any sound I can make is better than silence.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

María del Pilar Kaladeen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

spread pandemic recovery africa india south america canada ukInternational

The millions of people not looking for work in the UK may be prioritising education, health and freedom

Economic inactivity is not always the worst option.

Around one in five British people of working age (16-64) are now outside the labour market. Neither in work nor looking for work, they are officially labelled as “economically inactive”.

Some of those 9.2 million people are in education, with many students not active in the labour market because they are studying full-time. Others are older workers who have chosen to take early retirement.

But that still leaves a large number who are not part of the labour market because they are unable to work. And one key driver of economic inactivity in recent years has been illness.

This increase in economic inactivity – which has grown since before the pandemic – is not just harming the economy, but also indicative of a deeper health crisis.

For those suffering ill health, there are real constraints on access to work. People with health-limiting conditions cannot just slot into jobs that are available. They need help to address the illnesses they have, and to re-engage with work through organisations offering supportive and healthy work environments.

And for other groups, such as stay-at-home parents, businesses need to offer flexible work arrangements and subsidised childcare to support the transition from economic inactivity into work.

The government has a role to play too. Most obviously, it could increase investment in the NHS. Rising levels of poor health are linked to years of under-investment in the health sector and economic inactivity will not be tackled without more funding.

Carrots and sticks

For the time being though, the UK government appears to prefer an approach which mixes carrots and sticks. In the March 2024 budget, for example, the chancellor cut national insurance by 2p as a way of “making work pay”.

But it is unclear whether small tax changes like this will have any effect on attracting the economically inactive back into work.

Jeremy Hunt also extended free childcare. But again, questions remain over whether this is sufficient to remove barriers to work for those with parental responsibilities. The high cost and lack of availability of childcare remain key weaknesses in the UK economy.

The benefit system meanwhile has been designed to push people into work. Benefits in the UK remain relatively ungenerous and hard to access compared with other rich countries. But labour shortages won’t be solved by simply forcing the economically inactive into work, because not all of them are ready or able to comply.

It is also worth noting that work itself may be a cause of bad health. The notion of “bad work” – work that does not pay enough and is unrewarding in other ways – can lead to economic inactivity.

There is also evidence that as work has become more intensive over recent decades, for some people, work itself has become a health risk.

The pandemic showed us how certain groups of workers (including so-called “essential workers”) suffered more ill health due to their greater exposure to COVID. But there are broader trends towards lower quality work that predate the pandemic, and these trends suggest improving job quality is an important step towards tackling the underlying causes of economic inactivity.

Freedom

Another big section of the economically active population who cannot be ignored are those who have retired early and deliberately left the labour market behind. These are people who want and value – and crucially, can afford – a life without work.

Here, the effects of the pandemic can be seen again. During those years of lockdowns, furlough and remote working, many of us reassessed our relationship with our jobs. Changed attitudes towards work among some (mostly older) workers can explain why they are no longer in the labour market and why they may be unresponsive to job offers of any kind.

And maybe it is from this viewpoint that we should ultimately be looking at economic inactivity – that it is actually a sign of progress. That it represents a move towards freedom from the drudgery of work and the ability of some people to live as they wish.

There are utopian visions of the future, for example, which suggest that individual and collective freedom could be dramatically increased by paying people a universal basic income.

In the meantime, for plenty of working age people, economic inactivity is a direct result of ill health and sickness. So it may be that the levels of economic inactivity right now merely show how far we are from being a society which actually supports its citizens’ wellbeing.

David Spencer has received funding from the ESRC.

uk pandemicInternational

Illegal Immigrants Leave US Hospitals With Billions In Unpaid Bills

Illegal Immigrants Leave US Hospitals With Billions In Unpaid Bills

By Autumn Spredemann of The Epoch Times

Tens of thousands of illegal…

By Autumn Spredemann of The Epoch Times

Tens of thousands of illegal immigrants are flooding into U.S. hospitals for treatment and leaving billions in uncompensated health care costs in their wake.

The House Committee on Homeland Security recently released a report illustrating that from the estimated $451 billion in annual costs stemming from the U.S. border crisis, a significant portion is going to health care for illegal immigrants.

With the majority of the illegal immigrant population lacking any kind of medical insurance, hospitals and government welfare programs such as Medicaid are feeling the weight of these unanticipated costs.

Apprehensions of illegal immigrants at the U.S. border have jumped 48 percent since the record in fiscal year 2021 and nearly tripled since fiscal year 2019, according to Customs and Border Protection data.

Last year broke a new record high for illegal border crossings, surpassing more than 3.2 million apprehensions.

And with that sea of humanity comes the need for health care and, in most cases, the inability to pay for it.

In January, CEO of Denver Health Donna Lynne told reporters that 8,000 illegal immigrants made roughly 20,000 visits to the city’s health system in 2023.

The total bill for uncompensated care costs last year to the system totaled $140 million, said Dane Roper, public information officer for Denver Health. More than $10 million of it was attributed to “care for new immigrants,” he told The Epoch Times.

Though the amount of debt assigned to illegal immigrants is a fraction of the total, uncompensated care costs in the Denver Health system have risen dramatically over the past few years.

The total uncompensated costs in 2020 came to $60 million, Mr. Roper said. In 2022, the number doubled, hitting $120 million.

He also said their city hospitals are treating issues such as “respiratory illnesses, GI [gastro-intenstinal] illnesses, dental disease, and some common chronic illnesses such as asthma and diabetes.”

“The perspective we’ve been trying to emphasize all along is that providing healthcare services for an influx of new immigrants who are unable to pay for their care is adding additional strain to an already significant uncompensated care burden,” Mr. Roper said.

He added this is why a local, state, and federal response to the needs of the new illegal immigrant population is “so important.”

Colorado is far from the only state struggling with a trail of unpaid hospital bills.

Dr. Robert Trenschel, CEO of the Yuma Regional Medical Center situated on the Arizona–Mexico border, said on average, illegal immigrants cost up to three times more in human resources to resolve their cases and provide a safe discharge.

“Some [illegal] migrants come with minor ailments, but many of them come in with significant disease,” Dr. Trenschel said during a congressional hearing last year.

“We’ve had migrant patients on dialysis, cardiac catheterization, and in need of heart surgery. Many are very sick.”

He said many illegal immigrants who enter the country and need medical assistance end up staying in the ICU ward for 60 days or more.

A large portion of the patients are pregnant women who’ve had little to no prenatal treatment. This has resulted in an increase in babies being born that require neonatal care for 30 days or longer.

Dr. Trenschel told The Epoch Times last year that illegal immigrants were overrunning healthcare services in his town, leaving the hospital with $26 million in unpaid medical bills in just 12 months.

ER Duty to Care

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act of 1986 requires that public hospitals participating in Medicare “must medically screen all persons seeking emergency care … regardless of payment method or insurance status.”

The numbers are difficult to gauge as the policy position of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is that it “will not require hospital staff to ask patients directly about their citizenship or immigration status.”

In southern California, again close to the border with Mexico, some hospitals are struggling with an influx of illegal immigrants.

American patients are enduring longer wait times for doctor appointments due to a nursing shortage in the state, two health care professionals told The Epoch Times in January.

A health care worker at a hospital in Southern California, who asked not to be named for fear of losing her job, told The Epoch Times that “the entire health care system is just being bombarded” by a steady stream of illegal immigrants.

“Our healthcare system is so overwhelmed, and then add on top of that tuberculosis, COVID-19, and other diseases from all over the world,” she said.

A newly-enacted law in California provides free healthcare for all illegal immigrants residing in the state. The law could cost taxpayers between $3 billion and $6 billion per year, according to recent estimates by state and federal lawmakers.

In New York, where the illegal immigration crisis has manifested most notably beyond the southern border, city and state officials have long been accommodating of illegal immigrants’ healthcare costs.

Since June 2014, when then-mayor Bill de Blasio set up The Task Force on Immigrant Health Care Access, New York City has worked to expand avenues for illegal immigrants to get free health care.

“New York City has a moral duty to ensure that all its residents have meaningful access to needed health care, regardless of their immigration status or ability to pay,” Mr. de Blasio stated in a 2015 report.

The report notes that in 2013, nearly 64 percent of illegal immigrants were uninsured. Since then, tens of thousands of illegal immigrants have settled in the city.

“The uninsured rate for undocumented immigrants is more than three times that of other noncitizens in New York City (20 percent) and more than six times greater than the uninsured rate for the rest of the city (10 percent),” the report states.

The report states that because healthcare providers don’t ask patients about documentation status, the task force lacks “data specific to undocumented patients.”

Some health care providers say a big part of the issue is that without a clear path to insurance or payment for non-emergency services, illegal immigrants are going to the hospital due to a lack of options.

“It’s insane, and it has been for years at this point,” Dana, a Texas emergency room nurse who asked to have her full name omitted, told The Epoch Times.

Working for a major hospital system in the greater Houston area, Dana has seen “a zillion” migrants pass through under her watch with “no end in sight.” She said many who are illegal immigrants arrive with treatable illnesses that require simple antibiotics. “Not a lot of GPs [general practitioners] will see you if you can’t pay and don’t have insurance.”

She said the “undocumented crowd” tends to arrive with a lot of the same conditions. Many find their way to Houston not long after crossing the southern border. Some of the common health issues Dana encounters include dehydration, unhealed fractures, respiratory illnesses, stomach ailments, and pregnancy-related concerns.

“This isn’t a new problem, it’s just worse now,” Dana said.

Medicaid Factor

One of the main government healthcare resources illegal immigrants use is Medicaid.

All those who don’t qualify for regular Medicaid are eligible for Emergency Medicaid, regardless of immigration status. By doing this, the program helps pay for the cost of uncompensated care bills at qualifying hospitals.

However, some loopholes allow access to the regular Medicaid benefits. “Qualified noncitizens” who haven’t been granted legal status within five years still qualify if they’re listed as a refugee, an asylum seeker, or a Cuban or Haitian national.

Yet the lion’s share of Medicaid usage by illegal immigrants still comes through state-level benefits and emergency medical treatment.

A Congressional report highlighted data from the CMS, which showed total Medicaid costs for “emergency services for undocumented aliens” in fiscal year 2021 surpassed $7 billion, and totaled more than $5 billion in fiscal 2022.

Both years represent a significant spike from the $3 billion in fiscal 2020.

An employee working with Medicaid who asked to be referred to only as Jennifer out of concern for her job, told The Epoch Times that at a state level, it’s easy for an illegal immigrant to access the program benefits.

Jennifer said that when exceptions are sent from states to CMS for approval, “denial is actually super rare. It’s usually always approved.”

She also said it comes as no surprise that many of the states with the highest amount of Medicaid spending are sanctuary states, which tend to have policies and laws that shield illegal immigrants from federal immigration authorities.

Moreover, Jennifer said there are ways for states to get around CMS guidelines. “It’s not easy, but it can and has been done.”

The first generation of illegal immigrants who arrive to the United States tend to be healthy enough to pass any pre-screenings, but Jennifer has observed that the subsequent generations tend to be sicker and require more access to care. If a family is illegally present, they tend to use Emergency Medicaid or nothing at all.

The Epoch Times asked Medicaid Services to provide the most recent data for the total uncompensated care that hospitals have reported. The agency didn’t respond.

Continue reading over at The Epoch Times

International

Fuel poverty in England is probably 2.5 times higher than government statistics show

The top 40% most energy efficient homes aren’t counted as being in fuel poverty, no matter what their bills or income are.

The cap set on how much UK energy suppliers can charge for domestic gas and electricity is set to fall by 15% from April 1 2024. Despite this, prices remain shockingly high. The average household energy bill in 2023 was £2,592 a year, dwarfing the pre-pandemic average of £1,308 in 2019.

The term “fuel poverty” refers to a household’s ability to afford the energy required to maintain adequate warmth and the use of other essential appliances. Quite how it is measured varies from country to country. In England, the government uses what is known as the low income low energy efficiency (Lilee) indicator.

Since energy costs started rising sharply in 2021, UK households’ spending powers have plummeted. It would be reasonable to assume that these increasingly hostile economic conditions have caused fuel poverty rates to rise.

However, according to the Lilee fuel poverty metric, in England there have only been modest changes in fuel poverty incidence year on year. In fact, government statistics show a slight decrease in the nationwide rate, from 13.2% in 2020 to 13.0% in 2023.

Our recent study suggests that these figures are incorrect. We estimate the rate of fuel poverty in England to be around 2.5 times higher than what the government’s statistics show, because the criteria underpinning the Lilee estimation process leaves out a large number of financially vulnerable households which, in reality, are unable to afford and maintain adequate warmth.

Energy security

In 2022, we undertook an in-depth analysis of Lilee fuel poverty in Greater London. First, we combined fuel poverty, housing and employment data to provide an estimate of vulnerable homes which are omitted from Lilee statistics.

We also surveyed 2,886 residents of Greater London about their experiences of fuel poverty during the winter of 2022. We wanted to gauge energy security, which refers to a type of self-reported fuel poverty. Both parts of the study aimed to demonstrate the potential flaws of the Lilee definition.

Introduced in 2019, the Lilee metric considers a household to be “fuel poor” if it meets two criteria. First, after accounting for energy expenses, its income must fall below the poverty line (which is 60% of median income).

Second, the property must have an energy performance certificate (EPC) rating of D–G (the lowest four ratings). The government’s apparent logic for the Lilee metric is to quicken the net-zero transition of the housing sector.

In Sustainable Warmth, the policy paper that defined the Lilee approach, the government says that EPC A–C-rated homes “will not significantly benefit from energy-efficiency measures”. Hence, the focus on fuel poverty in D–G-rated properties.

Generally speaking, EPC A–C-rated homes (those with the highest three ratings) are considered energy efficient, while D–G-rated homes are deemed inefficient. The problem with how Lilee fuel poverty is measured is that the process assumes that EPC A–C-rated homes are too “energy efficient” to be considered fuel poor: the main focus of the fuel poverty assessment is a characteristic of the property, not the occupant’s financial situation.

In other words, by this metric, anyone living in an energy-efficient home cannot be considered to be in fuel poverty, no matter their financial situation. There is an obvious flaw here.

Around 40% of homes in England have an EPC rating of A–C. According to the Lilee definition, none of these homes can or ever will be classed as fuel poor. Even though energy prices are going through the roof, a single-parent household with dependent children whose only income is universal credit (or some other form of benefits) will still not be considered to be living in fuel poverty if their home is rated A-C.

The lack of protection afforded to these households against an extremely volatile energy market is highly concerning.

In our study, we estimate that 4.4% of London’s homes are rated A-C and also financially vulnerable. That is around 171,091 households, which are currently omitted by the Lilee metric but remain highly likely to be unable to afford adequate energy.

In most other European nations, what is known as the 10% indicator is used to gauge fuel poverty. This metric, which was also used in England from the 1990s until the mid 2010s, considers a home to be fuel poor if more than 10% of income is spent on energy. Here, the main focus of the fuel poverty assessment is the occupant’s financial situation, not the property.

Were such alternative fuel poverty metrics to be employed, a significant portion of those 171,091 households in London would almost certainly qualify as fuel poor.

This is confirmed by the findings of our survey. Our data shows that 28.2% of the 2,886 people who responded were “energy insecure”. This includes being unable to afford energy, making involuntary spending trade-offs between food and energy, and falling behind on energy payments.

Worryingly, we found that the rate of energy insecurity in the survey sample is around 2.5 times higher than the official rate of fuel poverty in London (11.5%), as assessed according to the Lilee metric.

It is likely that this figure can be extrapolated for the rest of England. If anything, energy insecurity may be even higher in other regions, given that Londoners tend to have higher-than-average household income.

The UK government is wrongly omitting hundreds of thousands of English households from fuel poverty statistics. Without a more accurate measure, vulnerable households will continue to be overlooked and not get the assistance they desperately need to stay warm.

Torran Semple receives funding from Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) grant EP/S023305/1.

John Harvey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

european uk pandemic-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International1 week ago

International1 week agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 week ago

International1 week agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Spread & Containment2 days ago

Spread & Containment2 days agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex