Uncategorized

How often do you lie? Deception researchers investigate how the recipient and the medium affect telling the truth

Researchers are interested in whether who you’re communicating with and how you’re interacting affect how likely you are to lie.

Prominent cases of purported lying continue to dominate the news cycle. Hunter Biden was charged with lying on a government form while purchasing a handgun. Republican Representative George Santos allegedly lied in many ways, including to donors through a third party in order to misuse the funds raised. The rapper Offset admitted to lying on Instagram about his wife, Cardi B, being unfaithful.

There are a number of variables that distinguish these cases. One is the audience: the faceless government, particular donors and millions of online followers, respectively. Another is the medium used to convey the alleged lie: on a bureaucratic form, through intermediaries and via social media.

Differences like these lead researchers like me to wonder what factors influence the telling of lies. Does a personal connection increase or decrease the likelihood of sticking to the truth? Are lies more prevalent on text or email than on the phone or in person?

An emerging body of empirical research is trying to answer these questions, and some of the findings are surprising. They hold lessons, too - for how to think about the areas of your life where you might be more prone to tell lies, and also about where to be most cautious in trusting what others are saying. As the recent director of The Honesty Project and author of “Honesty: The Philosophy and Psychology of a Neglected Virtue,” I am especially interested in whether most people tend to be honest or not.

Figuring out the frequency of lies

Most research on lying asks participants to self-report their lying behavior, say during the past day or week. (Whether you can trust liars to tell the truth about lying is another question.)

The classic study on lying frequency was conducted by psychologist Bella DePaulo in the mid-1990s. It focused on face-to-face interactions and used a group of student participants and another group of volunteers from the community around the University of Virginia. The community members averaged one lie per day, while the students averaged two lies per day. This result became the benchmark finding in the field of honesty research and helped lead to an assumption among many researchers that lying is commonplace.

But averages do not describe individuals. It could be that each person in the group tells one or two lies per day. But it’s also possible that there are some people who lie voraciously and others who lie very rarely.

In an influential 2010 study, this second scenario is indeed what Michigan State University communication researcher Kim Serota and his colleagues found. Out of 1,000 American participants, 59.9% claimed not to have told a single lie in the past 24 hours. Of those who admitted they did lie, most said they’d told very few lies. Participants reported 1,646 lies in total, but half of them came from just 5.3% of the participants.

This general pattern in the data has been replicated several times. Lying tends to be rare, except in the case of a small group of frequent liars.

Does the medium make a difference?

Might lying become more frequent under various conditions? What if you don’t just consider face-to-face interactions, but introduce some distance by communicating via text, email or the phone?

Research suggests the medium doesn’t matter much. For instance, a 2014 study by Northwestern University communication researcher Madeline Smith and her colleagues found that when participants were asked to look at their 30 most recent text messages, 23% said there were no deceptive texts. For the rest of the group, the vast majority said that 10% or fewer of their texts contained lies.

Recent research by David Markowitz at the University of Oregon successfully replicated earlier findings that had compared the rates of lying using different technologies. Are lies more common on text, the phone or on email? Based on survey data from 205 participants, Markowitz found that on average, people told 1.08 lies per day, but once again with the distribution of lies skewed by some frequent liars.

Not only were the percentages fairly low, but the differences between the frequency with which lies were told via different media were not large. Still, it might be surprising to find that, say, lying on video chat was more common than lying face-to-face, with lying on email being least likely.

A couple of factors could be playing a role. Recordability seems to rein in the lies – perhaps knowing that the communication leaves a record raises worries about detection and makes lying less appealing. Synchronicity seems to matter too. Many lies occur in the heat of the moment, so it makes sense that when there’s a delay in communication, as with email, lying would decrease.

Does the audience change things?

In addition to the medium, does the intended receiver of a potential lie make any difference?

Initially you might think that people are more inclined to lie to strangers than to friends and family, given the impersonality of the interaction in the one case and the bonds of care and concern in the other. But matters are a bit more complicated.

In her classic work, DePaulo found that people tend to tell what she called “everyday lies” more often to strangers than family members. To use her examples, these are smaller lies like “told her (that) her muffins were the best ever” and “exaggerated how sorry I was to be late.” For instance, DePaulo and her colleague Deborah Kashy reported that participants in one of their studies lied less than once per 10 social interactions with spouses and children.

However, when it came to serious lies about things like affairs or injuries, for instance, the pattern flipped. Now, 53% of serious lies were to close partners in the study’s community participants, and the proportion jumped up to 72.7% among student volunteers. Perhaps not surprisingly, in these situations people might value not damaging their relationships more than they value the truth. Other data also finds participants tell more lies to friends and family members than to strangers.

Investigating the truth about lies

It is worth emphasizing that these are all initial findings. Further replication is needed, and cross-cultural studies using non-Western participants are scarce. Additionally, there are many other variables that could be examined, such as age, gender, religion and political affiliation.

When it comes to honesty, though, I find the results, in general, promising. Lying seems to happen rarely for many people, even toward strangers and even via social media and texting. Where people need to be especially discerning, though, is in identifying – and avoiding – the small number of rampant liars out there. If you’re one of them yourself, maybe you never realized that you’re actually in a small minority.

From 2020-2023, Christian B. Miller received funding from the John Templeton Foundation for the Honesty Project, which advancd research on the psychology and philosophy of honesty.

bondsUncategorized

Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more

New Zillow research suggests the spring home shopping season may see a second wave this summer if mortgage rates fall

The post Homes listed for sale in…

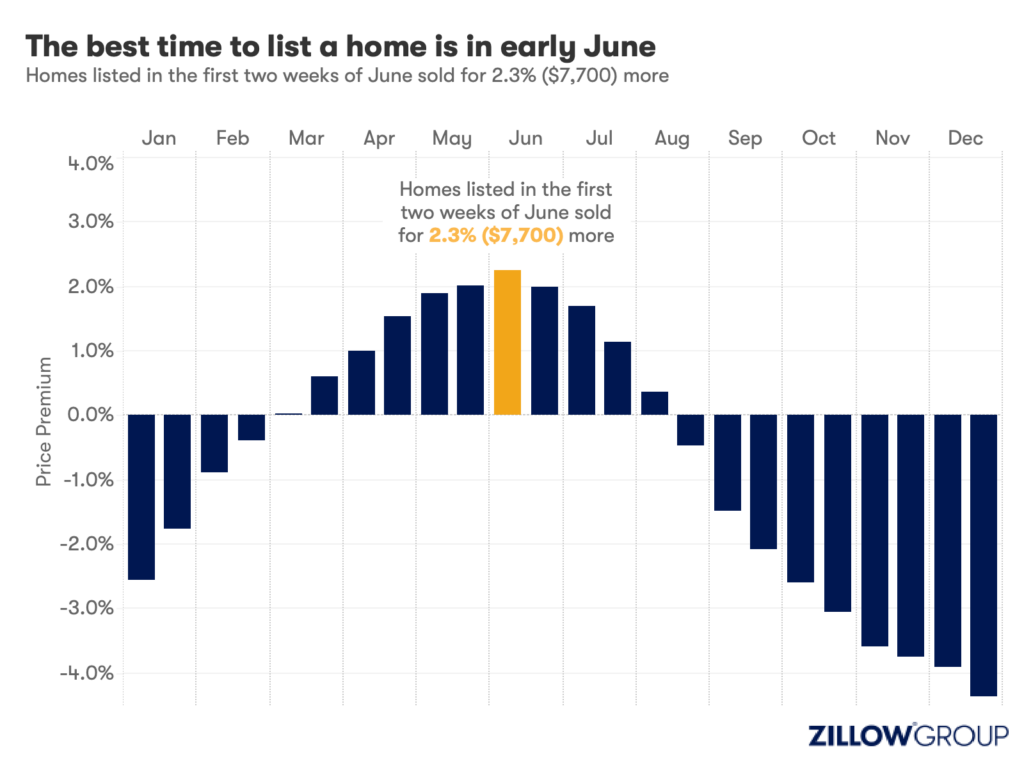

- A Zillow analysis of 2023 home sales finds homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more.

- The best time to list a home for sale is a month later than it was in 2019, likely driven by mortgage rates.

- The best time to list can be as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York and Philadelphia.

Spring home sellers looking to maximize their sale price may want to wait it out and list their home for sale in the first half of June. A new Zillow® analysis of 2023 sales found that homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more, a $7,700 boost on a typical U.S. home.

The best time to list consistently had been early May in the years leading up to the pandemic. The shift to June suggests mortgage rates are strongly influencing demand on top of the usual seasonality that brings buyers to the market in the spring. This home-shopping season is poised to follow a similar pattern as that in 2023, with the potential for a second wave if the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates midyear or later.

The 2.3% sale price premium registered last June followed the first spring in more than 15 years with mortgage rates over 6% on a 30-year fixed-rate loan. The high rates put home buyers on the back foot, and as rates continued upward through May, they were still reassessing and less likely to bid boldly. In June, however, rates pulled back a little from 6.79% to 6.67%, which likely presented an opportunity for determined buyers heading into summer. More buyers understood their market position and could afford to transact, boosting competition and sale prices.

The old logic was that sellers could earn a premium by listing in late spring, when search activity hit its peak. Now, with persistently low inventory, mortgage rate fluctuations make their own seasonality. First-time home buyers who are on the edge of qualifying for a home loan may dip in and out of the market, depending on what’s happening with rates. It is almost certain the Federal Reserve will push back any interest-rate cuts to mid-2024 at the earliest. If mortgage rates follow, that could bring another surge of buyers later this year.

Mortgage rates have been impacting affordability and sale prices since they began rising rapidly two years ago. In 2022, sellers nationwide saw the highest sale premium when they listed their home in late March, right before rates barreled past 5% and continued climbing.

Zillow’s research finds the best time to list can vary widely by metropolitan area. In 2023, it was as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York. Thirty of the top 35 largest metro areas saw for-sale listings command the highest sale prices between May and early July last year.

Zillow also found a wide range in the sale price premiums associated with homes listed during those peak periods. At the hottest time of the year in San Jose, homes sold for 5.5% more, a $88,000 boost on a typical home. Meanwhile, homes in San Antonio sold for 1.9% more during that same time period.

| Metropolitan Area | Best Time to List | Price Premium | Dollar Boost |

| United States | First half of June | 2.3% | $7,700 |

| New York, NY | First half of July | 2.4% | $15,500 |

| Los Angeles, CA | First half of May | 4.1% | $39,300 |

| Chicago, IL | First half of June | 2.8% | $8,800 |

| Dallas, TX | First half of June | 2.5% | $9,200 |

| Houston, TX | Second half of April | 2.0% | $6,200 |

| Washington, DC | Second half of June | 2.2% | $12,700 |

| Philadelphia, PA | First half of July | 2.4% | $8,200 |

| Miami, FL | First half of June | 2.3% | $12,900 |

| Atlanta, GA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $8,700 |

| Boston, MA | Second half of May | 3.5% | $23,600 |

| Phoenix, AZ | First half of June | 3.2% | $14,700 |

| San Francisco, CA | Second half of February | 4.2% | $50,300 |

| Riverside, CA | First half of May | 2.7% | $15,600 |

| Detroit, MI | First half of July | 3.3% | $7,900 |

| Seattle, WA | First half of June | 4.3% | $31,500 |

| Minneapolis, MN | Second half of May | 3.7% | $13,400 |

| San Diego, CA | Second half of April | 3.1% | $29,600 |

| Tampa, FL | Second half of June | 2.1% | $8,000 |

| Denver, CO | Second half of May | 2.9% | $16,900 |

| Baltimore, MD | First half of July | 2.2% | $8,200 |

| St. Louis, MO | First half of June | 2.9% | $7,000 |

| Orlando, FL | First half of June | 2.2% | $8,700 |

| Charlotte, NC | Second half of May | 3.0% | $11,000 |

| San Antonio, TX | First half of June | 1.9% | $5,400 |

| Portland, OR | Second half of April | 2.6% | $14,300 |

| Sacramento, CA | First half of June | 3.2% | $17,900 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $4,700 |

| Cincinnati, OH | Second half of April | 2.7% | $7,500 |

| Austin, TX | Second half of May | 2.8% | $12,600 |

| Las Vegas, NV | First half of June | 3.4% | $14,600 |

| Kansas City, MO | Second half of May | 2.5% | $7,300 |

| Columbus, OH | Second half of June | 3.3% | $10,400 |

| Indianapolis, IN | First half of July | 3.0% | $8,100 |

| Cleveland, OH | First half of July | 3.4% | $7,400 |

| San Jose, CA | First half of June | 5.5% | $88,400 |

The post Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more appeared first on Zillow Research.

federal reserve pandemic home sales mortgage rates interest ratesUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

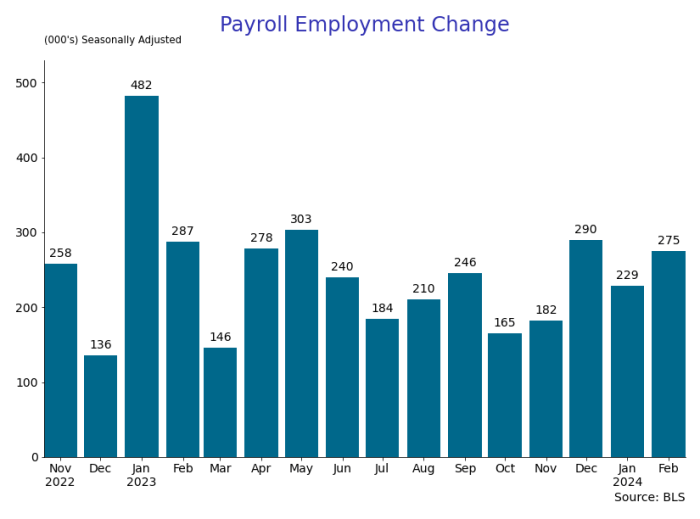

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

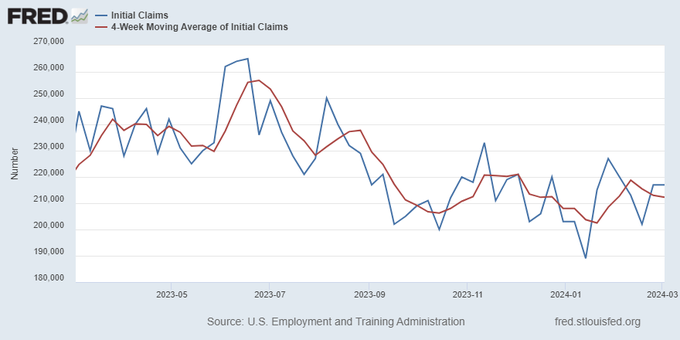

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemployment-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex