Spread & Containment

How America’s response to 9/11 contributed to our national decline

In his long war against America, Osama bin Laden has won a sweeping if posthumous victory. The U.S. reaction to the 9/11 attack he masterminded is like the cytokine storm that can occur when COVID-19 attacks us: the defensive measures our bodies mount…

By William A. Galston

In his long war against America, Osama bin Laden has won a sweeping if posthumous victory. The U.S. reaction to the 9/11 attack he masterminded is like the cytokine storm that can occur when COVID-19 attacks us: the defensive measures our bodies mount go too far and damage the vital organs our antibodies were meant to protect. The 9/11 era began in Afghanistan, and now it has ended there, in humiliating defeat.

The United States is weaker, more divided, and less respected than it was two decades ago, and we have surrendered the unchallenged preeminence we then enjoyed. Although our response to 9/11 is not solely responsible for these negative developments, it has certainly contributed to them.

It did not have to be this way. Misjudgments by four successive presidents led us to lose focus on the purpose of our presence in Afghanistan, invade Iraq under mistaken premises, violate our own red line in Syria, sign what amounted to a surrender agreement with the Taliban, and leave Kabul under the worst imaginable circumstances. Whom the gods would destroy, goes the proverb, they first make mad.

We had to react forcefully to al-Qaeda’s murderous assault, and we did. But counterfactual history helps us understand how badly our reaction went astray. If we had simply deposed the Taliban and accepted their surrender, which they offered and we spurned, captured Osama bin Laden at Tora Bora, and stopped there, we would have been much better off than we are today. The invasion of Iraq did depose a murderous thug but at the cost of removing the key barrier to the spread of Iranian influence in the Middle East. And Iran is a far greater threat to our interests and our friends than Iraq ever was. We did not have to respond to the 9/11 attack in this way, but the attack on our homeland gave our leaders the opportunity and the predicate to commit this enormous series of blunders.

At the end of the 20th century, the United States bestrode the world like a colossus. We had no military or economic peers, and our ideological victory over the antagonists of liberal democracy seemed total. September 11 changed all this. Our excessive focus on the Middle East diverted us from the geopolitical forces that that were reshaping the world to our disadvantage. While America looked elsewhere, Russia recovered and China rose, with consequences stretching from Crimea to the Taiwan Strait to the factories and small towns of America’s heartland. Now we must face the consequences with a weakened hand.

“Our excessive focus on the Middle East diverted us from the geopolitical forces that that were reshaping the world to our disadvantage.”

America led the world, not alone, but at the head of friendships and alliances forged in the crucible of World War II. There were constant tensions within these structures, of course, but in the main, our friends and allies believed that they could count on us for stability and sound judgment. Not anymore. The misguided invasion of Iraq created deep divisions between the United States and Europe, our surrender of Syria to Russian influence made the world doubt the strength of our purpose, and our pell-mell departure from Afghanistan has infuriated and saddened even our closest supporters. It is not often—indeed it may be unprecedented—that the United States is castigated by both the government and the opposition in the House of Commons.

We were hardly a united country on Sept. 10, 2001, but our divisions are far worse today. The attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, which but for the actions of brave Americans would have included the U.S. Capitol as well, should have unified the country—and at the beginning it did. President George W. Bush’s forceful response to the terrorists garnered bipartisan praise, and his effort to prevent the demonization of Muslim Americans proved remarkably effective. For a while, Congress worked in rare harmony across party lines to pass essential measures.

But as debates over the treatment of detainees and the invasion of Iraq escalated, unity gave way to bitter recriminations that exacerbated Americans’ mistrust of government and undermined confidence in the role of foreign policy, defense, and intelligence expertise. Partisan divisions over the Islamic religion and Muslim immigrants steadily widened, laying the foundation for the controversial restrictions imposed in the opening weeks of the Trump administration. September 11 has left us with a legacy of fear—on the right, the fear of more terrorist attacks; on the left, fear that our response to this possibility will infringe civil liberties and open the door to discrimination against Muslims and other minorities.

The opportunity costs of our post-9/11 policy choices have been enormous. Since 2001, the United States has spent about $2 trillion in direct warfighting costs in Iraq and Afghanistan. One estimate places the total cost at $4 trillion, not counting the “long tail” outlays for treating the physical and mental damage these wars have inflicted on thousands of the best men and women our country has to offer.

It would be naïve to suggest that all this money would otherwise have been put to productive use in domestic public policy or the private sector. But one thing is clear: During years of fiscal restraints on discretionary spending during the past decade, our wars in the Middle East received funding from accounts to which the official budget limits did not apply.

“A more measured response to the attack on our homeland would have made us stronger at home, with no loss of security.”

Because domestic policy had no such safety valve, important government functions suffered, including the emergency health stockpile that was all but empty when we needed it the most in the early months of the pandemic. At the same time, our failure to raise taxes to fund our post-9/11 military engagements wars guaranteed steady upward pressure on the national debt. A more measured response to the attack on our homeland would have made us stronger at home, with no loss of security. This alternative course, moreover, would have given the Department of Defense more bandwidth to focus on the military modernization needed to counter the great-power threats we now face.

The manner of our withdrawal from Afghanistan threatens to make all this worse. Because we are leaving behind thousands of Afghans who worked with us, we may well create another generation of American fighting men and women who doubt the morality of their government and wonder whether their sacrifices were worth it. And there is an awful symmetry: The era that began in tragedy with an attack on Americans from Afghanistan ended with an attack on Americans in Afghanistan.

This said, we cannot afford to squander our energy in endless “Who lost Kabul?” debates. We should close the book on the 9/11 era, confine our policies in the Middle East to defending our friends and our essential interests, and focus instead on the task before us—doing what is necessary at home and abroad to arrest our decline and remain fully competitive in the struggle to define world order in the 21st century.

congress trump pandemic covid-19 treatment antibodies spread iran europe russia chinaSpread & Containment

There Goes The Fed’s Inflation Target: Goldman Sees Terminal Rate 100bps Higher At 3.5%

There Goes The Fed’s Inflation Target: Goldman Sees Terminal Rate 100bps Higher At 3.5%

Two years ago, we first said that it’s only a matter…

Two years ago, we first said that it's only a matter of time before the Fed admits it is unable to rsolve the so-called "last mile" of inflation and that as a result, the old inflation target of 2% is no longer viable.

At some point Fed will concede it has no control over supply. That's when we will start getting leaks of raising the inflation target

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) June 21, 2022

Then one year ago, we correctly said that while everyone was paying attention elsewhere, the inflation target had already been hiked to 2.8%... on the way to even more increases.

The new inflation target has been set to 2.8%. The rest is just narrative fill for the next 2 years. https://t.co/X1xYkecyPy

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) February 21, 2023

And while the Fed still pretends it can one day lower inflation to 2% even as it prepares to cut rates as soon as June, moments ago Goldman published a note from its economics team which had to balls to finally call a spade a spade, and concluded that - as party of the Fed's next big debate, i.e., rethinking the Neutral rate - both the neutral and terminal rate, a polite euphemism for the inflation target, are much higher than conventional wisdom believes, and that as a result Goldman is "penciling in a terminal rate of 3.25-3.5% this cycle, 100bp above the peak reached last cycle."

There is more in the full Goldman note, but below we excerpt the key fragments:

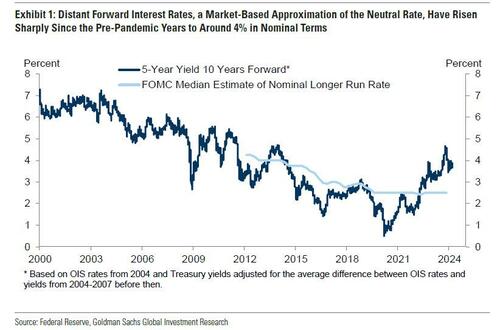

We argued last cycle that the long-run neutral rate was not as low as widely thought, perhaps closer to 3-3.5% in nominal terms than to 2-2.5%. We have also argued this cycle that the short-run neutral rate could be higher still because the fiscal deficit is much larger than usual—in fact, estimates of the elasticity of the neutral rate to the deficit suggest that the wider deficit might boost the short-term neutral rate by 1-1.5%. Fed economists have also offered another reason why the short-term neutral rate might be elevated, namely that broad financial conditions have not tightened commensurately with the rise in the funds rate, limiting transmission to the economy.

Over the coming year, Fed officials are likely to debate whether the neutral rate is still as low as they assumed last cycle and as the dot plot implies....

...Translation: raising the neutral rate estimate is also the first step to admitting that the traditional 2% inflation target is higher than previously expected. And once the Fed officially crosses that particular Rubicon, all bets are off.

... Their thinking is likely to be influenced by distant forward market rates, which have risen 1-2pp since the pre-pandemic years to about 4%; by model-based estimates of neutral, whose earlier real-time values have been revised up by roughly 0.5pp on average to about 3.5% nominal and whose latest values are little changed; and by their perception of how well the economy is performing at the current level of the funds rate.

The bank's conclusion:

We expect Fed officials to raise their estimates of neutral over time both by raising their long-run neutral rate dots somewhat and by concluding that short-run neutral is currently higher than long-run neutral. While we are fairly confident that Fed officials will not be comfortable leaving the funds rate above 5% indefinitely once inflation approaches 2% and that they will not go all the way back to 2.5% purely in the name of normalization, we are quite uncertain about where in between they will ultimately land.

Because the economy is not sensitive enough to small changes in the funds rate to make it glaringly obvious when neutral has been reached, the terminal or equilibrium rate where the FOMC decides to leave the funds rate is partly a matter of the true neutral rate and partly a matter of the perceived neutral rate. For now, we are penciling in a terminal rate of 3.25-3.5% this cycle, 100bps above the peak reached last cycle. This reflects both our view that neutral is higher than Fed officials think and our expectation that their thinking will evolve.

Not that this should come as a surprise: as a reminder, with the US now $35.5 trillion in debt and rising by $1 trillion every 100 days, we are fast approaching the Minsky Moment, which means the US has just a handful of options left: losing the reserve currency status, QEing the deficit and every new dollar in debt, or - the only viable alternative - inflating it all away. The only question we had before is when do "serious" economists make the same admission.

Meanwhile, nothing changes: total US debt jumps $57BN on March 15, to a record $34.543 trillion.

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) March 19, 2024

Three ways this ends: inflate it away, QE it all, or reserve status collapse

They now have.

And while we have discussed the staggering consequences of raising the inflation target by just 1% from 2% to 3% on everything from markets, to economic growth (instead of doubling every 35 years at 2% inflation target, prices would double every 23 years at 3%), and social cohesion, we will soon rerun the analysis again as the implications are profound. For now all you need to know is that with the US about to implicitly hit the overdrive of dollar devaluation, anything that is non-fiat will be much more preferable over fiat alternatives.

Much more in the full Goldman note available to pro subs in the usual place.

Spread & Containment

Household Net Interest Income Falls As Rates Spike

A Bloomberg article from this morning offered an excellent array of charts detailing the shifts in interest payment flows amid rising rates. The historical…

A Bloomberg article from this morning offered an excellent array of charts detailing the shifts in interest payment flows amid rising rates. The historical anomaly was both surprising and contradicted our priors.

10 Key Points:

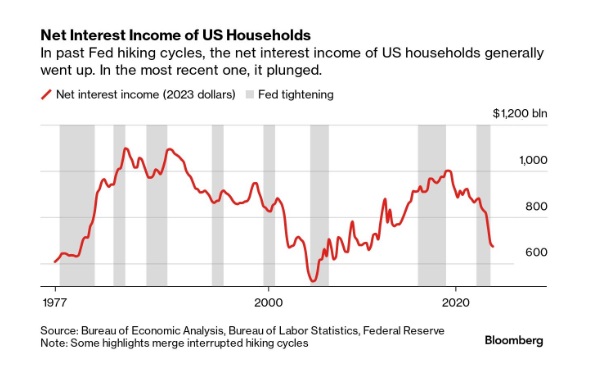

- Historical Anomaly: This is the first time in the last fifty years that a Federal Reserve rate hike cycle has led to a significant drop in household net interest income.

- Interest Expense Increase: Since the Fed began raising rates in March 2022, Americans’ annual interest expenses on debts like mortgages and credit cards have surged by nearly $420 billion.

- Interest Income Lag: The increase in interest income during the same period was only about $280 billion, resulting in a net decline in household interest income, a departure from past trends.

- Consumer Debt Influence: The recent rate hikes impacted household finances more because of a higher proportion of consumer credit, which adjusts more quickly to rate changes, increasing interest costs.

- Banks and Savers: Banks have been slow to pass on higher interest rates to depositors, and the prolonged period of low rates before 2022 may have discouraged savers from actively seeking better returns.

- Shift in Wealth: There’s been a shift from interest-bearing assets to stocks, with dividends surpassing interest payments as a source of unearned income during the pandemic.

- Distributional Discrepancy: Higher interest rates benefit wealthier individuals who own interest-earning assets, whereas lower-income earners face the brunt of increased debt servicing costs, exacerbating economic inequality.

- Job Market Impact: Typically, Fed rate hikes affect households through the job market, as businesses cut costs, potentially leading to layoffs or wage suppression, though this hasn’t occurred yet in the current cycle.

- Economic Impact: The distribution of interest income and debt servicing means that rate increases transfer money from those more likely to spend (and thus stimulate the economy) to those less likely to increase consumption, potentially dampening economic activity.

- No Immediate Relief: Expectations for the Fed to reduce rates have diminished, indicating that high-interest expenses for households may persist.

Spread & Containment

TJ Maxx and Marshalls follow Costco and Target on upcoming closures

Many of these stores have information customers need to know.

U.S. consumers have come to increasingly rely on the near ubiquity of convenience stores and big-box retailers.

Many of us depend on these stores being open practically all day, every day, even during some of the biggest holidays. After all, Black Friday beckons retail stores to open just hours after a Thanksgiving Day dinner in hopes of attracting huge crowds of shoppers in search of early holiday sales.

Related: Walmart announces more store closures for 2024

And it's largely true that before the covid pandemic most of our favorite stores were open all the time. Practically nothing — from inclement weather to bad news to holidays — could shut down a major operation like Walmart (WMT) or Target (TGT) .

Then the pandemic hit, and it turned everything we thought we knew about retail operations upside down.

Everything from grocery stores to shopping malls shut down in an effort to contain potential spread. And when they finally reopened to the public, different stores took different precautionary measures. Some monitored how many shoppers were inside at once, while others implemented foot-traffic rules dictating where one could enter and exit an aisle. And almost every one of them mandated wearing masks at one point or another.

Though these safety measures seem like a distant memory, one relic from the early 2020s remains firmly a part of our new American retail life.

Store closures announced for spring 2024

Many retailers have learned to adapt after a volatile start to this third decade, and in many ways this requires serving customers better and treating employees better to retain a workforce.

In some cases, the changes also reflect a change in shopping behavior, as more customers order online and leave more breathing room for brick-and-mortar operations. This also means more time for employees.

Thanks to this, big retailers have recently changed how they operate, especially during holiday hours, with Walmart recently saying it would close during Thanksgiving to give employees more time to spend with loved ones.

"I am delighted to share that once again, we'll be closing our doors for Thanksgiving this year," Walmart U.S. CEO John Furner told associates in a video posted to Twitter in November. "Thanksgiving is such a special day during a very busy season. We want you to spend that day at home with family and loved ones."

Other retailers have now followed suit, with Costco (COST) , Aldi, and Target all saying they would close their doors for 24 hours on Easter Sunday, March 31.

Now, the stores that operate under TJX Cos. (TJX) will also shut down during the holiday, including HomeGoods, TJ Maxx and Marshalls.

Though it closed on Thanksgiving, Walmart says it will remain open for shoppers on Easter.

Here's a list of stores that are closing for Easter 2024:

- Target

- Costco

- Aldi

- TJ Maxx

- Marshalls

- HomeGoods

- Publix

- Macy's

- Best Buy

- Apple

- ACE Hardware

Others are expected to remain open, including:

- Walmart

- Ikea

- Petco

- Home Depot

Most of the stores closing on Sunday will reopen for regular business hours on Monday.

spread pandemic-

Spread & Containment7 days ago

Spread & Containment7 days agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex