International

Financing for sustainable development is clogged

The IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings are a time when financing for sustainable development gets attention. This year, it was apparent that the main channels…

By Homi Kharas, Charlotte Rivard

The IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings are a time when financing for sustainable development gets attention. This year, it was apparent that the main channels are clogged.

To see why, it is useful to start with an understanding of the core elements of sustainable development financing. There are many channels, each with its own drivers.

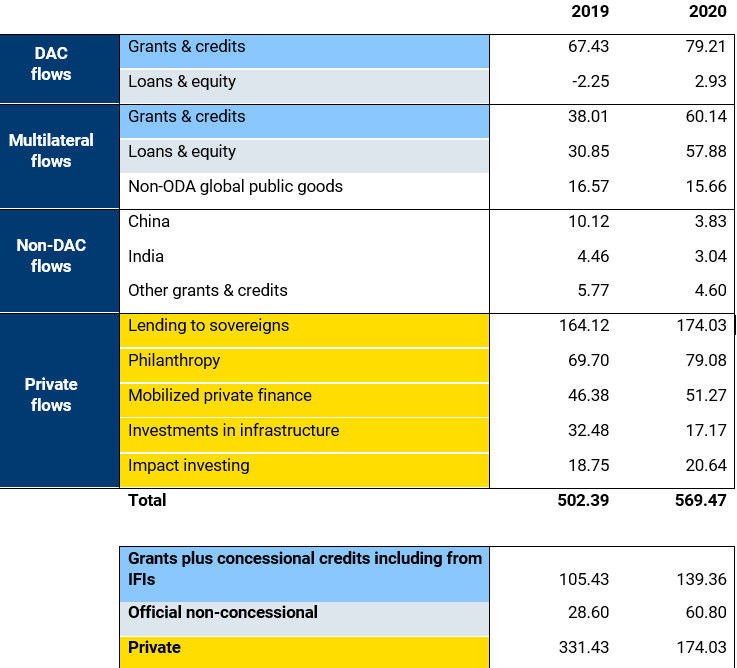

As Table 1 below shows, external financing in support of sustainable development objectives is in the range of $500 billion to $600 billion. These figures include a number of different sources of financing for sustainable investment, including aid, loans, and private flows. We adjust net official development assistance (ODA) for sums that cannot be used for sustainable development investments: donor administrative costs, in-country refugee charges, and humanitarian assistance. What’s left—approximating what is called country programmable aid—can be used for investments to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

If developing countries can develop sound project pipelines and improve their policy and institutional structures and if advanced economies give political and financial backing to unclogging finance channels, it is possible to move the agenda forward.

The nature of official flows is reasonably well-understood. Private flows are less easy to categorize, which we can divide into five categories: (i) lending to sovereigns and their enterprises through bond markets and syndicated bank credits; (ii) private philanthropy, which is now of significant proportions; (iii) private finance mobilized into investment projects in co-financing with multilateral agencies (the International Finance Corporation is the major mobilizer); (iv) private provision of infrastructure (mostly in electric power generation, but also toll roads and hospitals); and (v) impact investing into a variety of sectors.

The smaller channels of development finance are closing or showing little prospects for improvement in the short to medium term. For example, even though there is much excitement about environmental, social, and governance investments and sustainable bonds, very little of this money flows to developing countries, and there is an increasing backlash against “greenwashing.” Private philanthropy is large but not organized in a systematic way and responds to the preferences of individual donors rather than being directed to the SDGs. Much is in the form of in-kind donations. And the flows from large emerging economies like China and India have slowed dramatically, starting—in the case of China—well before the pandemic, and now becoming increasingly small as recipient countries shelve investment projects. From a policy perspective, other than the engagement of these creditors in debt relief (see below), there is little that can be done by policymakers in the short run to provide more resources.

For this reason, the real policy debate is over the three main channels that account for around two-thirds of the flows: aid, official nonconcessional lending, and private lending to sovereigns or to entities with a sovereign guarantee. Policymakers need to find a way to unclog these channels.

Table 1: Broadly-defined net international development financing contributions (current USD, billions)Source: Author’s calculations, based on data from OECD statistics, World Bank International Debt statistics, UN financial statistics, Boston University Global Development Policy Center, Government of India Ministry of External Affairs, Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, OECD TOSSD, World Bank Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI) database, and the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN).

Aid

It is commendable that aid has continued to grow even while advanced economies have seen their own domestic situations worsen. Overall aid from Development Assistance Committee countries rose in 2020 and 2021, with increases from countries such as Germany, Sweden, Norway, the United States, and France. Multilateral aid rose even faster, with disbursements from the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and the World Bank Group’s International Development Association (IDA) providing much-needed countercyclical financing. Aid continued to rise in 2021 and important international funds were replenished, including IDA and the Green Climate Fund.

However, aid in some important countries, notably the U.K., fell in 2020 and again in 2021. In aggregate, aid grew by 0.6 percent in 2021 in real terms, excluding vaccines for COVID-19. At one level, it is commendable that aid continued to grow despite real budget difficulties in every donor country. At another level, however, aid increases appear modest. The ODA increase in 2020 was modest—less than 0.1 percent of the $12 trillion that governments of donor countries spent on their domestic fiscal stimulus packages in 2020.

During the Spring Meetings, the pressures on aid were evident. Officials, especially from Europe, talked about needing to accommodate in-donor costs for housing Ukrainian refugees from aid budgets. Afghanistan, which prior to February 24 was expected to figure prominently in the discussions, was hardly brought up, and a U.N. appeal for humanitarian funding in March came up $2 billion short—the pledged amounts were 45 percent less than the estimated need. Afghanistan now has the highest infant and child mortality in the world.

Given the pressures on aid to respond to humanitarian crises, the Ukraine war, spillover impacts on food and fuel crises, potential debt crises, and the ongoing need for vaccinations and pandemic-related spending, prospects for increases in aid for sustainable development appear bleak.

Official nonconcessional lending

Official financial institutions provided $60 billion during 2020, almost entirely from multilateral institutions that stepped up countercyclical financing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Even this, however, was unable to prevent a bifurcated global recovery: Rich countries have mostly regained their pre-pandemic output levels, while developing countries still fall far short. A further concern is that the pandemic forced many developing country governments to slash investment spending and close schools, compromising the potential for future growth.

Against this backdrop, a major announcement at the Spring Meetings was the approval of the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) facility, funded in part through a reallocation of special drawing rights (SDRs) that had been issued to rich countries in the initial response to the pandemic. The RST is aiming to raise SDR 33 billion (roughly $45 billion equivalent). Its big breakthrough, however, is not the volume of funding but the terms: The loans will have a 20-year maturity, a 10 ½ year grace period, and an interest rate slightly above the SDR interest rate that is currently 0.5 percent.

Another major announcement was a second surge financing package by the World Bank Group, which aims to provide $170 billion in sustainable development finance over the 15 months between April 2022 and June 2023. However, the World Bank warns that this program will substantially erode the available capital of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the main lending arm of the World Bank to middle-income countries. IBRD will be forced to cut its lending by one-third in fiscal year 2024 and beyond under current assumptions.

Other multilateral development banks face the same problem as IBRD. They have lent considerable amounts to respond to the pandemic, leaving them undercapitalized as they look to the future. For this reason, the channel of providing more official nonconcessional lending is clogged.

Private capital

The Spring Meetings had their fair share of warnings about impending debt crises in developing countries and, indeed, credit ratings from the major agencies show that risk is rising. During 2020 and 2021, 42 developing countries had their credit rating downgraded by at least one of the three major ratings agencies, and an additional 33 had their outlook downgraded. The Common Framework for debt treatment beyond the debt service suspension initiative seems stuck. Only three countries are participating (Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia) and negotiations in each case have been ongoing for too long, with progress measured more by process change than by actual results.

As a sharp reminder of why credit ratings are important, consider that developing countries with an investment grade rating pay an average real interest of 3.6 percent on borrowing from capital markets; those with less than investment grade ratings pay an additional 10 percentage points in interest. At those interest rates, it becomes very difficult to maintain creditworthiness. The only option for a finance minister is to avoid new borrowing and to try to limit fiscal deficits. This is why developing countries were complaining during the Spring Meetings about their lack of fiscal space. Given these conditions in financial markets, there is considerable pessimism that developing countries will be able to profitably return to capital markets on a broad scale.

The way forward

This assessment of what is blocking long-term finance for development suggests three main areas for policy action:

- Aid remains the cornerstone of sustainable development finance, but it is in such short supply relative to demand that it must be leveraged—through guarantees, funding institutional innovation, or providing fresh capital to development institutions.

- International financial institutions are an efficient way of leveraging capital but are rapidly running out of headroom. They will need fresh capital soon, or else middle-income developing countries will be left with few options. Small improvements may be possible on the margin through balance sheet optimization, but these are a distraction from the core need for additional funding.

- Private finance can only restart if new flows are protected from the legacy of existing debt. This means either accelerating debt workout or use of guarantees and other forms of risk pooling and risk shifting, preferential treatment for funds used for core SDG and climate investments, and/or lending to off-sovereign balance sheet public wealth funds or development banks.

If developing countries can develop sound project pipelines and improve their policy and institutional structures and if advanced economies give political and financial backing to unclogging finance channels, it is possible to move the agenda forward. Big asks—no wonder the mood at the Spring Meetings was somber.

stimulus pandemic covid-19 bonds treatment mortality recovery interest rates stimulus india europe france germany sweden ukraine chinaInternational

There will soon be one million seats on this popular Amtrak route

“More people are taking the train than ever before,” says Amtrak’s Executive Vice President.

While the size of the United States makes it hard for it to compete with the inter-city train access available in places like Japan and many European countries, Amtrak trains are a very popular transportation option in certain pockets of the country — so much so that the country’s national railway company is expanding its Northeast Corridor by more than one million seats.

Related: This is what it's like to take a 19-hour train from New York to Chicago

Running from Boston all the way south to Washington, D.C., the route is one of the most popular as it passes through the most densely populated part of the country and serves as a commuter train for those who need to go between East Coast cities such as New York and Philadelphia for business.

Veronika Bondarenko

Amtrak launches new routes, promises travelers ‘additional travel options’

Earlier this month, Amtrak announced that it was adding four additional Northeastern routes to its schedule — two more routes between New York’s Penn Station and Union Station in Washington, D.C. on the weekend, a new early-morning weekday route between New York and Philadelphia’s William H. Gray III 30th Street Station and a weekend route between Philadelphia and Boston’s South Station.

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

According to Amtrak, these additions will increase Northeast Corridor’s service by 20% on the weekdays and 10% on the weekends for a total of one million additional seats when counted by how many will ride the corridor over the year.

“More people are taking the train than ever before and we’re proud to offer our customers additional travel options when they ride with us on the Northeast Regional,” Amtrak Executive Vice President and Chief Commercial Officer Eliot Hamlisch said in a statement on the new routes. “The Northeast Regional gets you where you want to go comfortably, conveniently and sustainably as you breeze past traffic on I-95 for a more enjoyable travel experience.”

Here are some of the other Amtrak changes you can expect to see

Amtrak also said that, in the 2023 financial year, the Northeast Corridor had nearly 9.2 million riders — 8% more than it had pre-pandemic and a 29% increase from 2022. The higher demand, particularly during both off-peak hours and the time when many business travelers use to get to work, is pushing Amtrak to invest into this corridor in particular.

To reach more customers, Amtrak has also made several changes to both its routes and pricing system. In the fall of 2023, it introduced a type of new “Night Owl Fare” — if traveling during very late or very early hours, one can go between cities like New York and Philadelphia or Philadelphia and Washington. D.C. for $5 to $15.

As travel on the same routes during peak hours can reach as much as $300, this was a deliberate move to reach those who have the flexibility of time and might have otherwise preferred more affordable methods of transportation such as the bus. After seeing strong uptake, Amtrak added this type of fare to more Boston routes.

The largest distances, such as the ones between Boston and New York or New York and Washington, are available at the lowest rate for $20.

stocks pandemic japan europeanInternational

The next pandemic? It’s already here for Earth’s wildlife

Bird flu is decimating species already threatened by climate change and habitat loss.

I am a conservation biologist who studies emerging infectious diseases. When people ask me what I think the next pandemic will be I often say that we are in the midst of one – it’s just afflicting a great many species more than ours.

I am referring to the highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza H5N1 (HPAI H5N1), otherwise known as bird flu, which has killed millions of birds and unknown numbers of mammals, particularly during the past three years.

This is the strain that emerged in domestic geese in China in 1997 and quickly jumped to humans in south-east Asia with a mortality rate of around 40-50%. My research group encountered the virus when it killed a mammal, an endangered Owston’s palm civet, in a captive breeding programme in Cuc Phuong National Park Vietnam in 2005.

How these animals caught bird flu was never confirmed. Their diet is mainly earthworms, so they had not been infected by eating diseased poultry like many captive tigers in the region.

This discovery prompted us to collate all confirmed reports of fatal infection with bird flu to assess just how broad a threat to wildlife this virus might pose.

This is how a newly discovered virus in Chinese poultry came to threaten so much of the world’s biodiversity.

The first signs

Until December 2005, most confirmed infections had been found in a few zoos and rescue centres in Thailand and Cambodia. Our analysis in 2006 showed that nearly half (48%) of all the different groups of birds (known to taxonomists as “orders”) contained a species in which a fatal infection of bird flu had been reported. These 13 orders comprised 84% of all bird species.

We reasoned 20 years ago that the strains of H5N1 circulating were probably highly pathogenic to all bird orders. We also showed that the list of confirmed infected species included those that were globally threatened and that important habitats, such as Vietnam’s Mekong delta, lay close to reported poultry outbreaks.

Mammals known to be susceptible to bird flu during the early 2000s included primates, rodents, pigs and rabbits. Large carnivores such as Bengal tigers and clouded leopards were reported to have been killed, as well as domestic cats.

Our 2006 paper showed the ease with which this virus crossed species barriers and suggested it might one day produce a pandemic-scale threat to global biodiversity.

Unfortunately, our warnings were correct.

A roving sickness

Two decades on, bird flu is killing species from the high Arctic to mainland Antarctica.

In the past couple of years, bird flu has spread rapidly across Europe and infiltrated North and South America, killing millions of poultry and a variety of bird and mammal species. A recent paper found that 26 countries have reported at least 48 mammal species that have died from the virus since 2020, when the latest increase in reported infections started.

Not even the ocean is safe. Since 2020, 13 species of aquatic mammal have succumbed, including American sea lions, porpoises and dolphins, often dying in their thousands in South America. A wide range of scavenging and predatory mammals that live on land are now also confirmed to be susceptible, including mountain lions, lynx, brown, black and polar bears.

The UK alone has lost over 75% of its great skuas and seen a 25% decline in northern gannets. Recent declines in sandwich terns (35%) and common terns (42%) were also largely driven by the virus.

Scientists haven’t managed to completely sequence the virus in all affected species. Research and continuous surveillance could tell us how adaptable it ultimately becomes, and whether it can jump to even more species. We know it can already infect humans – one or more genetic mutations may make it more infectious.

At the crossroads

Between January 1 2003 and December 21 2023, 882 cases of human infection with the H5N1 virus were reported from 23 countries, of which 461 (52%) were fatal.

Of these fatal cases, more than half were in Vietnam, China, Cambodia and Laos. Poultry-to-human infections were first recorded in Cambodia in December 2003. Intermittent cases were reported until 2014, followed by a gap until 2023, yielding 41 deaths from 64 cases. The subtype of H5N1 virus responsible has been detected in poultry in Cambodia since 2014. In the early 2000s, the H5N1 virus circulating had a high human mortality rate, so it is worrying that we are now starting to see people dying after contact with poultry again.

It’s not just H5 subtypes of bird flu that concern humans. The H10N1 virus was originally isolated from wild birds in South Korea, but has also been reported in samples from China and Mongolia.

Recent research found that these particular virus subtypes may be able to jump to humans after they were found to be pathogenic in laboratory mice and ferrets. The first person who was confirmed to be infected with H10N5 died in China on January 27 2024, but this patient was also suffering from seasonal flu (H3N2). They had been exposed to live poultry which also tested positive for H10N5.

Species already threatened with extinction are among those which have died due to bird flu in the past three years. The first deaths from the virus in mainland Antarctica have just been confirmed in skuas, highlighting a looming threat to penguin colonies whose eggs and chicks skuas prey on. Humboldt penguins have already been killed by the virus in Chile.

How can we stem this tsunami of H5N1 and other avian influenzas? Completely overhaul poultry production on a global scale. Make farms self-sufficient in rearing eggs and chicks instead of exporting them internationally. The trend towards megafarms containing over a million birds must be stopped in its tracks.

To prevent the worst outcomes for this virus, we must revisit its primary source: the incubator of intensive poultry farms.

Diana Bell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

genetic pandemic mortality spread deaths south korea south america europe uk chinaInternational

This is the biggest money mistake you’re making during travel

A retail expert talks of some common money mistakes travelers make on their trips.

Travel is expensive. Despite the explosion of travel demand in the two years since the world opened up from the pandemic, survey after survey shows that financial reasons are the biggest factor keeping some from taking their desired trips.

Airfare, accommodation as well as food and entertainment during the trip have all outpaced inflation over the last four years.

Related: This is why we're still spending an insane amount of money on travel

But while there are multiple tricks and “travel hacks” for finding cheaper plane tickets and accommodation, the biggest financial mistake that leads to blown travel budgets is much smaller and more insidious.

This is what you should (and shouldn’t) spend your money on while abroad

“When it comes to traveling, it's hard to resist buying items so you can have a piece of that memory at home,” Kristen Gall, a retail expert who heads the financial planning section at points-back platform Rakuten, told Travel + Leisure in an interview. “However, it's important to remember that you don't need every souvenir that catches your eye.”

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

According to Gall, souvenirs not only have a tendency to add up in price but also weight which can in turn require one to pay for extra weight or even another suitcase at the airport — over the last two months, airlines like Delta (DAL) , American Airlines (AAL) and JetBlue Airways (JBLU) have all followed each other in increasing baggage prices to in some cases as much as $60 for a first bag and $100 for a second one.

While such extras may not seem like a lot compared to the thousands one might have spent on the hotel and ticket, they all have what is sometimes known as a “coffee” or “takeout effect” in which small expenses can lead one to overspend by a large amount.

‘Save up for one special thing rather than a bunch of trinkets…’

“When traveling abroad, I recommend only purchasing items that you can't get back at home, or that are small enough to not impact your luggage weight,” Gall said. “If you’re set on bringing home a souvenir, save up for one special thing, rather than wasting your money on a bunch of trinkets you may not think twice about once you return home.”

Along with the immediate costs, there is also the risk of purchasing things that go to waste when returning home from an international vacation. Alcohol is subject to airlines’ liquid rules while certain types of foods, particularly meat and other animal products, can be confiscated by customs.

While one incident of losing an expensive bottle of liquor or cheese brought back from a country like France will often make travelers forever careful, those who travel internationally less frequently will often be unaware of specific rules and be forced to part with something they spent money on at the airport.

“It's important to keep in mind that you're going to have to travel back with everything you purchased,” Gall continued. “[…] Be careful when buying food or wine, as it may not make it through customs. Foods like chocolate are typically fine, but items like meat and produce are likely prohibited to come back into the country.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic france-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex