International

Egypt’s Swift Elimination of Hepatitis C: A Model for Success Globally

Hepatitis C is a serious disease that affects more than 58 million people globally.1 Although endemic in many countries, it is possible to eliminate the…

Hepatitis C is a serious disease that affects more than 58 million people globally.1 Although endemic in many countries, it is possible to eliminate the disease within entire populations. Unfortunately, this has only been done in a limited number of countries. Here we analyze the successes of those countries and what it takes to eliminate hepatitis C on a national scale. The first of these requirements is the scientific means and biomedical tools necessary to detect and treat both those who are actively infected and those at risk. Next is the political will, popular support, and leadership for the meticulous implementation of those tools. Third is the organization and existence of a health system capable of diagnosing, treating, and conducting follow-ups with the entirety of the population. Finally, the cost of diagnostics and drugs must be affordable for both the government and the citizens. All these components are needed for a successful program.

Hepatitis C is a blood borne viral infection that affects the liver by causing inflammation and swelling of liver tissues. Acute infections with this virus are generally asymptomatic, but when left untreated, approximately 80% of those acute infections will develop into chronic infections. Of cases that reach chronic status, up to 20% will develop cirrhosis within 10-15 years of initial infection. For cases that progress to the cirrhosis stage, 20% will develop cirrhosis-related liver failure, and an estimated 3-5% of cirrhotic liver cases will progress to hepatocellular carcinoma.2

Source: www.racgp.org.au/afp/2013/july/hepatitis-c

The diagnostic process for hepatitis C includes two steps. The first step is to screen for exposure to the hepatitis C virus. Exposure is determined by measuring the presence of hepatitis C antibodies in the blood, which are produced whenever a person is infected. After confirmation that hepatitis C antibodies are present, an RNA test is performed to determine if there is active virus replication. This test uses a polymerase chain reaction to measure the levels of hepatitis C virus RNA in the blood. An additional PCR test may also be performed to determine the viral genotype, which plays an important role in deciding what drugs to use. There are currently six different hepatitis C genotypes present across the globe. In the United States, genotypes 1, 2, and 3 make up over 98% of infections.3

Acute HCV infection is easily detected in the body and readily triggers the body’s innate immune response. In the innate response, the immune system releases natural killer cells (NKs), proinflammatory cytokines, and the interferon-stimulated gene response (IGE), which work to interfere with HCV replication and kill off infected hepatocytes. The innate response is often not enough to curb the replication of the hepatitis C virus in liver tissue, but it allows the body time to mount an adaptive immune response. In the adaptive immune response, the body generates B-cells to induce the production of broadly neutralizing antibodies. These specialized antibodies are useful because they can recognize and block viral entry across multiple strains of hepatitis C. The immune system also releases two types of T-cells: helper CD4+ cells, which prompt B-cells to make antibodies, and cytotoxic CD8+ cells, which kill cells already infected with the hepatitis C virus.

Interestingly, up to 30% of hepatitis C infections will clear independently.4 Research about these spontaneous clearance cases reveals the importance of having robust and sustained B-cell and T-cell responses. This research is especially useful as scientists work to develop an effective vaccine.

Source: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/piiB9780128032336000175

In the absence of a vaccine, hepatitis C is still highly treatable. The first generation of hepatitis C drugs focused on boosting the body’s immune system response using interferon injections. These injections, however, were susceptible to disease relapse and came with many side effects. Soon after, treatment evolved, and long-acting pegylated alpha interferons in conjunction with ribavirin became the new standard. Through pegylation, scientists increased the molecule size of the interferons to slow down the rate at which the drug was absorbed, thus increasing the amount of time the drug remained in the body. While this combination of drugs was a step up from interferon monotherapy, there were still numerous side effects, and treatment efficacy varied greatly by genotype. In the early 2010s, a new generation of drugs, called direct-acting antivirals, became available. Instead of boosting immune responses, these drugs were designed to attack specific molecular targets known to play a role in the replication of the hepatitis C virus. There are three classes of direct-acting antivirals: inhibitors of the NS3/4A protease, those that target the NS5A replicase factor, and those that target the NS5B RNA polymerase. Most direct-acting antiviral regimens consist of taking a daily pill for an average of three months, with interval RNA testing to assess how well the treatment works. A hepatitis C virus RNA level under 25 IU/mL at least three months after completing therapeutic treatment is considered a clinical cure, and at least 95% of patients who finish a course of direct-acting antiviral therapy achieve this status.5

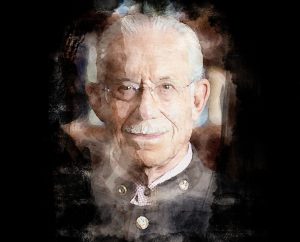

Hepatitis C has been eliminated from some low-income countries, including Egypt and Georgia. These countries have demonstrated that it is possible to eliminate this disease in low and high-income countries, and that it can be done relatively inexpensively compared to other medical issues. If we look at the success of Egypt, we can determine that the most important part of eliminating a disease nationwide is the political will to do so. When President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and the Egyptian government recognized the burden of hepatitis C within its borders, they committed to solving it. In September 2019, the Egyptian government implemented its 100 Million Healthy Lives program. The initiative was financed by a $250 million loan from the World Bank, supported by President el-Sisi, and managed by the Ministry of Health and Dr. Hala Zaid. The seven-month program was one of the world’s largest public health screening campaigns and allowed Egypt to efficiently screen and treat its population over the age of 12 for hepatitis C.

Source: www.hu.edu.eg/100-million-healthy-lives-campaign/heliopolis-university/

Along with political will, a successful national eradication program needs the collective support of the people, the government, and the healthcare system. Explicit government commitment can generate popular consent by generating buy-in for scientists and public health officials to create new policies and infrastructure. As we’ve seen with COVID-19, government commitment and promotion can generate public support by encouraging citizens to participate in the program. To gain popular consent for the 100 Million Healthy Lives Program, Egypt’s Ministry of Health flooded the country with advertisements for the campaign: newspapers, TV and radio stations, social media platforms, billboards, and posters featuring President el-Sisi.

Source: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8087425/#B35

Once the political will and popular consent have been established, there must be a health system capable of reaching everybody in the country. Egypt, fortunately, has a central health system that enabled the 100 Million Lives campaign to reach its entire population. Its program followed a simple cascade of individuals from screening to post-treatment follow-up. The government started by identifying and recruiting its screening population. The first phase targeted citizens 18 years and older but later expanded to include those over the age of 12. The next step was to inform citizens about the program and encourage them to participate. In addition to a widespread promotional media campaign, citizens were encouraged to register for appointments on the centralized campaign website, www.stophcv.eg, and get tested at one of thousands of testing centers and mobile units stationed around the country. During their principal appointment, citizens were given an antibody test to identify viral exposure. Those with positive antibody results were then referred to specialized testing centers for PCR testing to confirm an active infection. Within 30 days of confirmed infection, the government was able to provide those individuals with three months of free treatment.6 Finally, citizens were retested at the end of their treatment regimens and provided a certificate of cure if found to be negative for infection. Throughout the program, 1.6 million adults tested positive for hepatitis C infections, 1.47 million accepted government-provided treatment at no cost, and an estimated 1.23 million Egyptian citizens with active hepatitis C infections were cured.7

For a large-scale screening and treatment program to work, the cost of diagnostics and drugs must be affordable to both the government and the people. Egypt was so successful in its price-lowering efforts that it was able to provide free testing and treatment for its entire population. Lowering these costs can be accomplished through negotiations or, in Egypt’s case, patent agreements. To lower the costs of its program, Egypt first declared the financial burden of distributing hepatitis C drugs as a contributor to its endemic status. This exempted the country from drug patent protection in accordance with the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights agreement. Egypt was then free to purchase active pharmaceutical ingredients for seven different direct-acting antivirals from India. Egyptian pharmaceutical companies then formulated these materials for a fraction of the market price, which can be as high as $84,000 in some high-income countries.8 This reduction in costs allowed the program to provide free treatment for all its citizens at a cost of just $45 USD to the Egyptian government. These efforts also allowed those who opted for private treatment to pay just $70 USD. If Egypt can successfully lower prices, there’s no reason the United States and other high-income countries should be paying 10–100 times more for the same tests and drugs. Some countries are already designing solutions to lower costs. The United States recently announced that the National Hepatitis C Elimination Program supports the development of a single diagnostic test in addition to a pharmaceutical subscription model, which would substantially streamline and lower the total cost of testing and treatment.9

The final element of a successful eradication program is its meticulous execution. The 100 Million Healthy Lives campaign was made possible by the dedication of political and healthcare stakeholders at all levels, including Wahid Doss, MD, who oversaw the program’s implementation. Egypt’s campaign employed over 60,000 physicians, nurses, data analysts, and newly trained volunteers, many of whom had no medical background.10 The government also used a virtual private network within its national healthcare service to report all the campaign results in real time. Program officials could track how many people were screened, the age distribution, and the population percentage covered. The efficiency of the central organization system also allowed screening for other public health diseases in Egypt, including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.

Although it is possible to design and execute a national program to eliminate hepatitis C, there are other reasons for optimism in eradicating it.

There is currently no vaccine for hepatitis C, but the ability to protect populations from getting the disease is important for curbing the incidence of new infections. Insights from spontaneous clearance cases and several other vaccines, like the pan-genotypic COVID-19 vaccine, have helped scientists develop promising methods for a hepatitis C vaccine. Research has shown that broadly neutralizing antibodies and robust and sustained T-cell responses are required to clear the disease. One promising method scientists use to induce the production of T-cells and neutralize antibodies is targeting conserved epitopes. An epitope is a specific part on the surface of a virus that T-cells can bind to and signal B-cells to produce hepatitis C antigen-specific antibodies. Conserved epitopes are T-cell targets that appear across multiple strains of hepatitis C which would allow the vaccine to work against a breadth of antigen variants.

With the incidence of hepatitis C rapidly increasing and almost half of United States citizens unaware of their infection status, the United States and other countries must act fast.11 While many countries possess biomedical science and are starting to recognize the urgency of the epidemic, it is important to note that if these programs are deficient in any one of these: the political will, popular consent, an effective healthcare system, low prices for drugs and diagnostics, or meticulous implementation, they are unlikely to succeed. The United States has unveiled a national plan to eliminate Hepatitis C within 5 years. While the U.S. has the tools to diagnose and treat its citizens, the fractured healthcare system and high drug costs make implementation and wide distribution very challenging.

While the U.S. has different mechanisms for determining drug prices than Egypt, the Inflation Reduction Act empowers the federal government to negotiate prices for certain drugs covered by the Medicare program. However, this is limited to the Medicare population and initially encompasses only ten drugs. The U.S. should explore broader and more comprehensive approaches to reduce healthcare costs for all Americans.

Even though many countries face these same barriers, it is still possible to eliminate the disease. It’s not the tools and expertise that these countries lack, it’s the political will and sustained funding. If it can be done in Egypt, it can be done in the United States, Europe, and around the world.

Read More

- www.researchgate.net/publication/280987023_T-lymphocyte_senescence_and_hepatitis_C_virus_infection

- www.researchgate.net/publication/280987023_T-lymphocyte_senescence_and_hepatitis_C_virus_infection

- www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554898/

- www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jvh.12866

- www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7132e1.htm

- www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMsr1912628?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

- www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8087425/#B35

- www.accessh.org/interviews/interview-with-wahid-doss-on-the-100-million-healthy-lives-project/

- www.statnews.com/2023/06/29/hepatitis-c-cure-access/

- www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMsr1912628

- www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/surveillanceguidance/HepatitisC.htm

William R. Haseltine, PhD, is chair and president of the think tank ACCESS Health International, a former Harvard Medical School and School of Public Health professor and founder of the university’s cancer and HIV/AIDS research departments. He is also the founder of more than a dozen biotechnology companies, including Human Genome Sciences.

The post Egypt’s Swift Elimination of Hepatitis C: A Model for Success Globally appeared first on Inside Precision Medicine.

cdc covid-19 vaccine treatment testing genome antibodies therapy rna india europeInternational

The next pandemic? It’s already here for Earth’s wildlife

Bird flu is decimating species already threatened by climate change and habitat loss.

I am a conservation biologist who studies emerging infectious diseases. When people ask me what I think the next pandemic will be I often say that we are in the midst of one – it’s just afflicting a great many species more than ours.

I am referring to the highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza H5N1 (HPAI H5N1), otherwise known as bird flu, which has killed millions of birds and unknown numbers of mammals, particularly during the past three years.

This is the strain that emerged in domestic geese in China in 1997 and quickly jumped to humans in south-east Asia with a mortality rate of around 40-50%. My research group encountered the virus when it killed a mammal, an endangered Owston’s palm civet, in a captive breeding programme in Cuc Phuong National Park Vietnam in 2005.

How these animals caught bird flu was never confirmed. Their diet is mainly earthworms, so they had not been infected by eating diseased poultry like many captive tigers in the region.

This discovery prompted us to collate all confirmed reports of fatal infection with bird flu to assess just how broad a threat to wildlife this virus might pose.

This is how a newly discovered virus in Chinese poultry came to threaten so much of the world’s biodiversity.

The first signs

Until December 2005, most confirmed infections had been found in a few zoos and rescue centres in Thailand and Cambodia. Our analysis in 2006 showed that nearly half (48%) of all the different groups of birds (known to taxonomists as “orders”) contained a species in which a fatal infection of bird flu had been reported. These 13 orders comprised 84% of all bird species.

We reasoned 20 years ago that the strains of H5N1 circulating were probably highly pathogenic to all bird orders. We also showed that the list of confirmed infected species included those that were globally threatened and that important habitats, such as Vietnam’s Mekong delta, lay close to reported poultry outbreaks.

Mammals known to be susceptible to bird flu during the early 2000s included primates, rodents, pigs and rabbits. Large carnivores such as Bengal tigers and clouded leopards were reported to have been killed, as well as domestic cats.

Our 2006 paper showed the ease with which this virus crossed species barriers and suggested it might one day produce a pandemic-scale threat to global biodiversity.

Unfortunately, our warnings were correct.

A roving sickness

Two decades on, bird flu is killing species from the high Arctic to mainland Antarctica.

In the past couple of years, bird flu has spread rapidly across Europe and infiltrated North and South America, killing millions of poultry and a variety of bird and mammal species. A recent paper found that 26 countries have reported at least 48 mammal species that have died from the virus since 2020, when the latest increase in reported infections started.

Not even the ocean is safe. Since 2020, 13 species of aquatic mammal have succumbed, including American sea lions, porpoises and dolphins, often dying in their thousands in South America. A wide range of scavenging and predatory mammals that live on land are now also confirmed to be susceptible, including mountain lions, lynx, brown, black and polar bears.

The UK alone has lost over 75% of its great skuas and seen a 25% decline in northern gannets. Recent declines in sandwich terns (35%) and common terns (42%) were also largely driven by the virus.

Scientists haven’t managed to completely sequence the virus in all affected species. Research and continuous surveillance could tell us how adaptable it ultimately becomes, and whether it can jump to even more species. We know it can already infect humans – one or more genetic mutations may make it more infectious.

At the crossroads

Between January 1 2003 and December 21 2023, 882 cases of human infection with the H5N1 virus were reported from 23 countries, of which 461 (52%) were fatal.

Of these fatal cases, more than half were in Vietnam, China, Cambodia and Laos. Poultry-to-human infections were first recorded in Cambodia in December 2003. Intermittent cases were reported until 2014, followed by a gap until 2023, yielding 41 deaths from 64 cases. The subtype of H5N1 virus responsible has been detected in poultry in Cambodia since 2014. In the early 2000s, the H5N1 virus circulating had a high human mortality rate, so it is worrying that we are now starting to see people dying after contact with poultry again.

It’s not just H5 subtypes of bird flu that concern humans. The H10N1 virus was originally isolated from wild birds in South Korea, but has also been reported in samples from China and Mongolia.

Recent research found that these particular virus subtypes may be able to jump to humans after they were found to be pathogenic in laboratory mice and ferrets. The first person who was confirmed to be infected with H10N5 died in China on January 27 2024, but this patient was also suffering from seasonal flu (H3N2). They had been exposed to live poultry which also tested positive for H10N5.

Species already threatened with extinction are among those which have died due to bird flu in the past three years. The first deaths from the virus in mainland Antarctica have just been confirmed in skuas, highlighting a looming threat to penguin colonies whose eggs and chicks skuas prey on. Humboldt penguins have already been killed by the virus in Chile.

How can we stem this tsunami of H5N1 and other avian influenzas? Completely overhaul poultry production on a global scale. Make farms self-sufficient in rearing eggs and chicks instead of exporting them internationally. The trend towards megafarms containing over a million birds must be stopped in its tracks.

To prevent the worst outcomes for this virus, we must revisit its primary source: the incubator of intensive poultry farms.

Diana Bell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

genetic pandemic mortality spread deaths south korea south america europe uk chinaInternational

This is the biggest money mistake you’re making during travel

A retail expert talks of some common money mistakes travelers make on their trips.

Travel is expensive. Despite the explosion of travel demand in the two years since the world opened up from the pandemic, survey after survey shows that financial reasons are the biggest factor keeping some from taking their desired trips.

Airfare, accommodation as well as food and entertainment during the trip have all outpaced inflation over the last four years.

Related: This is why we're still spending an insane amount of money on travel

But while there are multiple tricks and “travel hacks” for finding cheaper plane tickets and accommodation, the biggest financial mistake that leads to blown travel budgets is much smaller and more insidious.

This is what you should (and shouldn’t) spend your money on while abroad

“When it comes to traveling, it's hard to resist buying items so you can have a piece of that memory at home,” Kristen Gall, a retail expert who heads the financial planning section at points-back platform Rakuten, told Travel + Leisure in an interview. “However, it's important to remember that you don't need every souvenir that catches your eye.”

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

According to Gall, souvenirs not only have a tendency to add up in price but also weight which can in turn require one to pay for extra weight or even another suitcase at the airport — over the last two months, airlines like Delta (DAL) , American Airlines (AAL) and JetBlue Airways (JBLU) have all followed each other in increasing baggage prices to in some cases as much as $60 for a first bag and $100 for a second one.

While such extras may not seem like a lot compared to the thousands one might have spent on the hotel and ticket, they all have what is sometimes known as a “coffee” or “takeout effect” in which small expenses can lead one to overspend by a large amount.

‘Save up for one special thing rather than a bunch of trinkets…’

“When traveling abroad, I recommend only purchasing items that you can't get back at home, or that are small enough to not impact your luggage weight,” Gall said. “If you’re set on bringing home a souvenir, save up for one special thing, rather than wasting your money on a bunch of trinkets you may not think twice about once you return home.”

Along with the immediate costs, there is also the risk of purchasing things that go to waste when returning home from an international vacation. Alcohol is subject to airlines’ liquid rules while certain types of foods, particularly meat and other animal products, can be confiscated by customs.

While one incident of losing an expensive bottle of liquor or cheese brought back from a country like France will often make travelers forever careful, those who travel internationally less frequently will often be unaware of specific rules and be forced to part with something they spent money on at the airport.

“It's important to keep in mind that you're going to have to travel back with everything you purchased,” Gall continued. “[…] Be careful when buying food or wine, as it may not make it through customs. Foods like chocolate are typically fine, but items like meat and produce are likely prohibited to come back into the country.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic franceInternational

As the pandemic turns four, here’s what we need to do for a healthier future

On the fourth anniversary of the pandemic, a public health researcher offers four principles for a healthier future.

Anniversaries are usually festive occasions, marked by celebration and joy. But there’ll be no popping of corks for this one.

March 11 2024 marks four years since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

Although no longer officially a public health emergency of international concern, the pandemic is still with us, and the virus is still causing serious harm.

Here are three priorities – three Cs – for a healthier future.

Clear guidance

Over the past four years, one of the biggest challenges people faced when trying to follow COVID rules was understanding them.

From a behavioural science perspective, one of the major themes of the last four years has been whether guidance was clear enough or whether people were receiving too many different and confusing messages – something colleagues and I called “alert fatigue”.

With colleagues, I conducted an evidence review of communication during COVID and found that the lack of clarity, as well as a lack of trust in those setting rules, were key barriers to adherence to measures like social distancing.

In future, whether it’s another COVID wave, or another virus or public health emergency, clear communication by trustworthy messengers is going to be key.

Combat complacency

As Maria van Kerkove, COVID technical lead for WHO, puts it there is no acceptable level of death from COVID. COVID complacency is setting in as we have moved out of the emergency phase of the pandemic. But is still much work to be done.

First, we still need to understand this virus better. Four years is not a long time to understand the longer-term effects of COVID. For example, evidence on how the virus affects the brain and cognitive functioning is in its infancy.

The extent, severity and possible treatment of long COVID is another priority that must not be forgotten – not least because it is still causing a lot of long-term sickness and absence.

Culture change

During the pandemic’s first few years, there was a question over how many of our new habits, from elbow bumping (remember that?) to remote working, were here to stay.

Turns out old habits die hard – and in most cases that’s not a bad thing – after all handshaking and hugging can be good for our health.

But there is some pandemic behaviour we could have kept, under certain conditions. I’m pretty sure most people don’t wear masks when they have respiratory symptoms, even though some health authorities, such as the NHS, recommend it.

Masks could still be thought of like umbrellas: we keep one handy for when we need it, for example, when visiting vulnerable people, especially during times when there’s a spike in COVID.

If masks hadn’t been so politicised as a symbol of conformity and oppression so early in the pandemic, then we might arguably have seen people in more countries adopting the behaviour in parts of east Asia, where people continue to wear masks or face coverings when they are sick to avoid spreading it to others.

Although the pandemic led to the growth of remote or hybrid working, presenteeism – going to work when sick – is still a major issue.

Encouraging parents to send children to school when they are unwell is unlikely to help public health, or attendance for that matter. For instance, although one child might recover quickly from a given virus, other children who might catch it from them might be ill for days.

Similarly, a culture of presenteeism that pressures workers to come in when ill is likely to backfire later on, helping infectious disease spread in workplaces.

At the most fundamental level, we need to do more to create a culture of equality. Some groups, especially the most economically deprived, fared much worse than others during the pandemic. Health inequalities have widened as a result. With ongoing pandemic impacts, for example, long COVID rates, also disproportionately affecting those from disadvantaged groups, health inequalities are likely to persist without significant action to address them.

Vaccine inequity is still a problem globally. At a national level, in some wealthier countries like the UK, those from more deprived backgrounds are going to be less able to afford private vaccines.

We may be out of the emergency phase of COVID, but the pandemic is not yet over. As we reflect on the past four years, working to provide clearer public health communication, avoiding COVID complacency and reducing health inequalities are all things that can help prepare for any future waves or, indeed, pandemics.

Simon Nicholas Williams has received funding from Senedd Cymru, Public Health Wales and the Wales Covid Evidence Centre for research on COVID-19, and has consulted for the World Health Organization. However, this article reflects the views of the author only, in his academic capacity at Swansea University, and no funding or organizational bodies were involved in the writing or content of this article.

vaccine treatment pandemic covid-19 spread social distancing uk world health organization-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex