Uncategorized

Dead billionaires whose foundations are thriving today can thank Henry VIII and Elizabeth I

The hefty sums many billionaires give away place them in an age-old debate about wealth and charity – and whether it’s appropriate for donors to have…

More than 230 of the world’s wealthiest people, including Elon Musk, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, have promised to give at least half of their fortunes to charity within their lifetimes or in their wills by signing the Giving Pledge. Some of the most affluent, including Jeff Bezos – who hadn’t signed the Giving Pledge by early 2023 – and MacKenzie Scott, his ex-wife – have declared that they will go further by giving most of their fortunes to charity before they die.

This movement stands in contrast to practices of many of the philanthropists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Industrial titans like oil baron John D. Rockefeller, automotive entrepreneur Henry Ford and steel magnate Andrew Carnegie established massive foundations that to this day have big pots of money at their disposal despite decades of charitable grantmaking. This kind of control over funds after death is usually illegal because of a you-can’t-take-it-with-you legal doctrine that originated 500 years ago in England.

Known as the Rule Against Perpetuities, it holds that control over property must cease within 21 years of a death. But there is a loophole in that rule for money given to charities, which theoretically can flow forever. Without it, many of the largest U.S. and British foundations would have closed their doors after disbursing all their funds long ago.

As a lawyer and researcher who studies nonprofit law and history, I wondered why American donors get to give from the grave.

Henry VIII had his eye on property

In a recent working paper that I wrote with my colleague Angela Eikenberry and Kenya Love, a graduate student, we explained that this debate goes back to the court of Henry VIII.

The Rule Against Perpetuities developed in response to political upheaval in the 1530s. The old feudal law made it almost impossible for most properties to be sold, foreclosed upon or have their ownership changed in any way.

At the time, a small number of people and the Catholic Church controlled most of the wealth in England. Henry VIII wanted to end this practice because it was difficult to tax property that never transferred, and property owners were mostly unaccountable to England’s monarchy. This encouraged fraud and led to a consolidation of wealth that threatened the king’s power.

As he sought to sever England’s ties to the Catholic Church, Henry had one eye on changing religious doctrine so he could divorce Catherine of Aragon, and the other on all the property that would become available when he booted out the church.

After splitting with the church and securing his divorce, he enacted a new property system giving the British monarchy a lot more power over wealth and used that power to seize property. Most of the property the king first took belonged to the church, but all property interests were more vulnerable under the new law.

Henry’s power grab angered the wealthy gentry, who launched a violent uprising known as the “Pilgrimage of Grace.”

After quelling that upheaval, Henry compromised by allowing the transfer of property from one generation to the next, but did not allow people to tell others how to use their property after they died. The courts later developed the Rule Against Perpetuities to allow people to transfer property to their children when they turned 21 years old.

At the same time, wealthy Englishmen were encouraged to give large sums of money and property to help the poor. Some of these funds had strings attached for longer than the 21 years.

Elizabeth I codified the rule

Elizabeth I, Henry VIII’s daughter with his ill-fated wife Anne Boleyn, became queen after his death. She used her reign to codify that previously informal charitable exception. By then it was the 1590s – a tough time for England, due to two wars, a pandemic, inflation and famine. Queen Elizabeth needed to prevent unrest without raising taxes even further than she already had.

Elizabeth’s solution was a new law decreed in 1601. Known as the “Statute of Charitable Uses,” it encouraged the wealthy to make big charitable donations and gave courts the power to enforce the terms of the gifts.

The monarchy believed that partnering with charities would ease the burdens of the state to aid the poor.

This concept remains popular today, especially among conservatives in the U.S. and U.K.

The charitable exception today

When the U.S. broke away from Great Britain and became an independent country, it wasn’t always certain that it would stick with the charitable exception.

Some states initially rejected British law, but by the early 19th century every state in the U.S. had adopted the Rule Against Perpetuities.

In the late 1800s, scholars started debating the value of the Rule Against Perpetuities, even as large foundations took advantage of Elizabeth’s philanthropy loophole. As of 2022, my co-authors and I had found that 40 U.S. states have ended or limited the rule and that every jurisdiction, including the District of Columbia, permits eternal control over donations.

Although this legal precept has endured, many scholars, charities and philanthropists question whether it makes sense to let foundations hang onto massive endowments with the goal of operating in the future in accordance with the wishes of a long-gone donor rather than spend that money to meet society’s needs today.

With such issues as climate change, spending more now could significantly decrease what it will cost later to resolve the problem.

Still other problems require change that is more likely to come from smaller nonprofits. In one example, many long-running foundations, including the Ford, Carnegie and Kellogg foundations, contributed large sums to help Flint, Michigan, after a shift in water supply brought lead in the tap water to poisonous levels. Some scholars argue this money undermined local community groups that better understood the needs of Flint’s residents.

Another argument is more philosophical: Why should dead billionaires get credit for helping to solve contemporary problems through the foundations bearing their names? This question often leads to a debate over whether history is being rewritten in ways that emphasize their philanthropy over the sometimes questionable ways that they secured their wealth.

Some of those very rich people who started massive foundations were racist and antisemitic. Does their use of this rule that’s been around for hundreds of years give them the right to influence how Americans solve 21st-century problems?

Nuri Heckler does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

oil pandemicUncategorized

Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more

New Zillow research suggests the spring home shopping season may see a second wave this summer if mortgage rates fall

The post Homes listed for sale in…

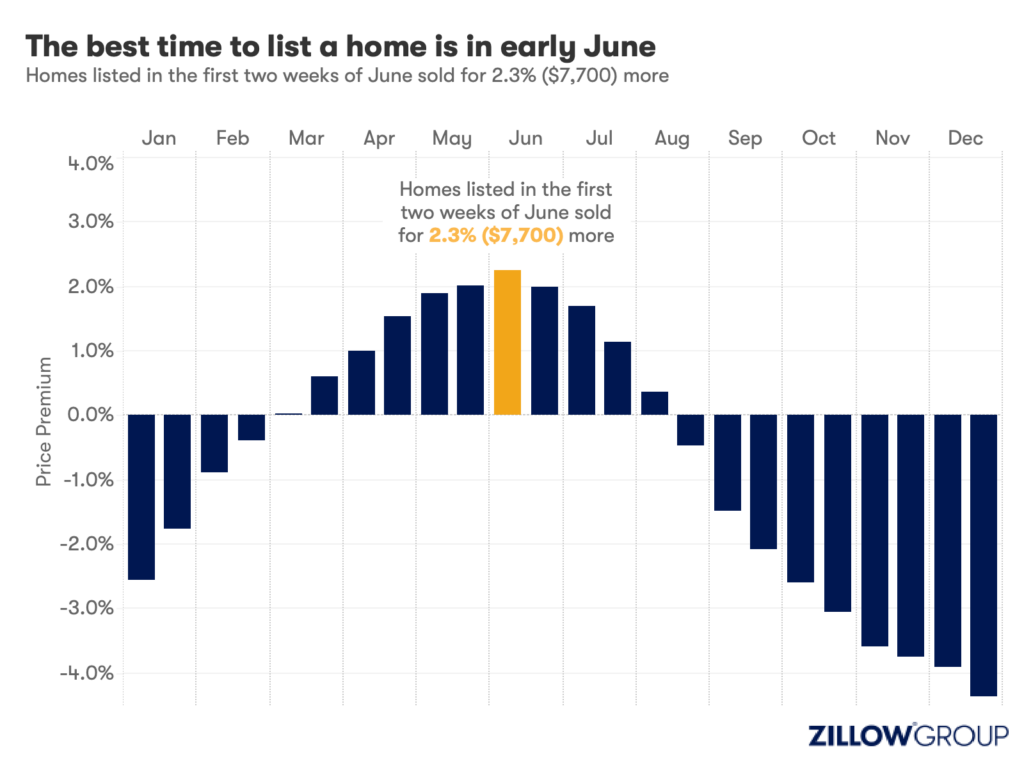

- A Zillow analysis of 2023 home sales finds homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more.

- The best time to list a home for sale is a month later than it was in 2019, likely driven by mortgage rates.

- The best time to list can be as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York and Philadelphia.

Spring home sellers looking to maximize their sale price may want to wait it out and list their home for sale in the first half of June. A new Zillow® analysis of 2023 sales found that homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more, a $7,700 boost on a typical U.S. home.

The best time to list consistently had been early May in the years leading up to the pandemic. The shift to June suggests mortgage rates are strongly influencing demand on top of the usual seasonality that brings buyers to the market in the spring. This home-shopping season is poised to follow a similar pattern as that in 2023, with the potential for a second wave if the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates midyear or later.

The 2.3% sale price premium registered last June followed the first spring in more than 15 years with mortgage rates over 6% on a 30-year fixed-rate loan. The high rates put home buyers on the back foot, and as rates continued upward through May, they were still reassessing and less likely to bid boldly. In June, however, rates pulled back a little from 6.79% to 6.67%, which likely presented an opportunity for determined buyers heading into summer. More buyers understood their market position and could afford to transact, boosting competition and sale prices.

The old logic was that sellers could earn a premium by listing in late spring, when search activity hit its peak. Now, with persistently low inventory, mortgage rate fluctuations make their own seasonality. First-time home buyers who are on the edge of qualifying for a home loan may dip in and out of the market, depending on what’s happening with rates. It is almost certain the Federal Reserve will push back any interest-rate cuts to mid-2024 at the earliest. If mortgage rates follow, that could bring another surge of buyers later this year.

Mortgage rates have been impacting affordability and sale prices since they began rising rapidly two years ago. In 2022, sellers nationwide saw the highest sale premium when they listed their home in late March, right before rates barreled past 5% and continued climbing.

Zillow’s research finds the best time to list can vary widely by metropolitan area. In 2023, it was as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York. Thirty of the top 35 largest metro areas saw for-sale listings command the highest sale prices between May and early July last year.

Zillow also found a wide range in the sale price premiums associated with homes listed during those peak periods. At the hottest time of the year in San Jose, homes sold for 5.5% more, a $88,000 boost on a typical home. Meanwhile, homes in San Antonio sold for 1.9% more during that same time period.

| Metropolitan Area | Best Time to List | Price Premium | Dollar Boost |

| United States | First half of June | 2.3% | $7,700 |

| New York, NY | First half of July | 2.4% | $15,500 |

| Los Angeles, CA | First half of May | 4.1% | $39,300 |

| Chicago, IL | First half of June | 2.8% | $8,800 |

| Dallas, TX | First half of June | 2.5% | $9,200 |

| Houston, TX | Second half of April | 2.0% | $6,200 |

| Washington, DC | Second half of June | 2.2% | $12,700 |

| Philadelphia, PA | First half of July | 2.4% | $8,200 |

| Miami, FL | First half of June | 2.3% | $12,900 |

| Atlanta, GA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $8,700 |

| Boston, MA | Second half of May | 3.5% | $23,600 |

| Phoenix, AZ | First half of June | 3.2% | $14,700 |

| San Francisco, CA | Second half of February | 4.2% | $50,300 |

| Riverside, CA | First half of May | 2.7% | $15,600 |

| Detroit, MI | First half of July | 3.3% | $7,900 |

| Seattle, WA | First half of June | 4.3% | $31,500 |

| Minneapolis, MN | Second half of May | 3.7% | $13,400 |

| San Diego, CA | Second half of April | 3.1% | $29,600 |

| Tampa, FL | Second half of June | 2.1% | $8,000 |

| Denver, CO | Second half of May | 2.9% | $16,900 |

| Baltimore, MD | First half of July | 2.2% | $8,200 |

| St. Louis, MO | First half of June | 2.9% | $7,000 |

| Orlando, FL | First half of June | 2.2% | $8,700 |

| Charlotte, NC | Second half of May | 3.0% | $11,000 |

| San Antonio, TX | First half of June | 1.9% | $5,400 |

| Portland, OR | Second half of April | 2.6% | $14,300 |

| Sacramento, CA | First half of June | 3.2% | $17,900 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $4,700 |

| Cincinnati, OH | Second half of April | 2.7% | $7,500 |

| Austin, TX | Second half of May | 2.8% | $12,600 |

| Las Vegas, NV | First half of June | 3.4% | $14,600 |

| Kansas City, MO | Second half of May | 2.5% | $7,300 |

| Columbus, OH | Second half of June | 3.3% | $10,400 |

| Indianapolis, IN | First half of July | 3.0% | $8,100 |

| Cleveland, OH | First half of July | 3.4% | $7,400 |

| San Jose, CA | First half of June | 5.5% | $88,400 |

The post Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more appeared first on Zillow Research.

federal reserve pandemic home sales mortgage rates interest ratesUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

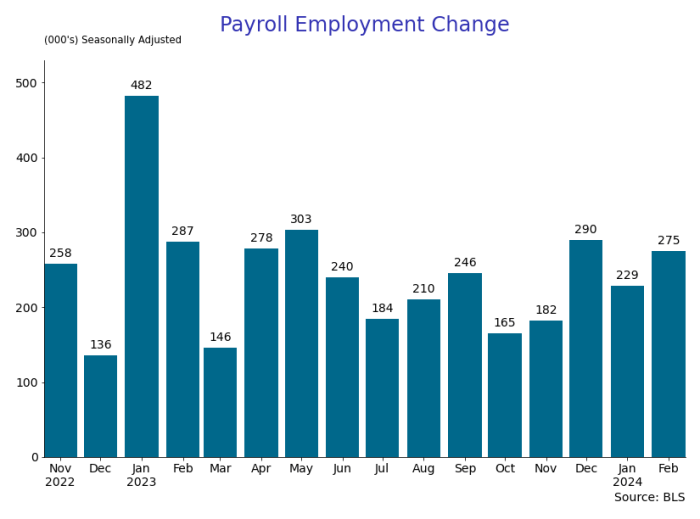

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

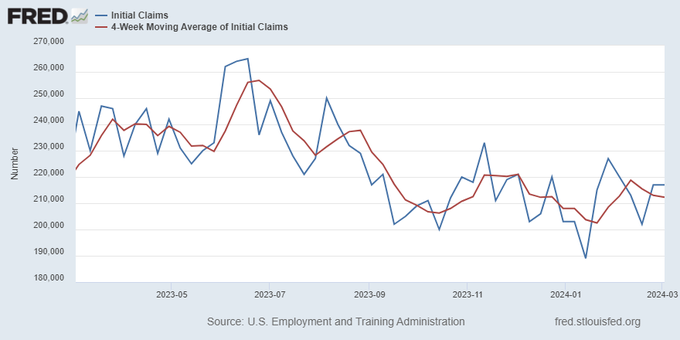

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemployment-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex