Are institutional investors the key silent partners of crypto?

More participation? The approval of the BTC ETF in October exacerbated the trend. “There is a much easier path to gaining this exposure.”

Imagine an institutional investor like an insurance company or pension fund decides that…

More participation? The approval of the BTC ETF in October exacerbated the trend. “There is a much easier path to gaining this exposure.”

Imagine an institutional investor like an insurance company or pension fund decides that it wants to test the cryptocurrency waters. Or maybe a large corporation is looking to buy some Bitcoin (BTC) to diversify its treasury holdings. One thing they’re unlikely to do is announce their intention beforehand.That could drive up the price of the digital asset they are trying to buy.

Thus, there’s often a lag between a large institution’s action — purchasing $100 million in Bitcoin, say — and its public announcement of such. “Institutional participation flows in cycles,” Diogo Mónica, co-founder and president of crypto custody bank Anchorage Digital, told Cointelegraph. “By the time you’re hearing about a new company adding crypto, we’ve typically been talking to them for many months.”

Has something like that been going on in the recent price run-up — when Bitcoin, Ether (ETH) and many other cryptocurrencies reached all-time highs? Were corporations and institutional investors stealthily gobbling up crypto through the early fall — so as not to raise the price while they were in accumulation phase — with its impact only this week being made manifest?

Wherefore the largest investors?

Kapil Rathi, CEO and co-founder of institutional cryptocurrency exchange CrossTower, told Cointelegraph, “Institutions have definitely been initiating or increasing Bitcoin allocations recently.” Much of it might have begun in early October, he allowed, as large investors were probably trying to get in ahead of the ProShares exchange-traded fund (ETF) launch — and it then became a seller after the launch — but still, “there has been strong passive support that has kept prices stable. This buying support has looked much more like institutional accumulation than retail buying in the way it has been executed.”

James Butterfill, investment strategist at digital asset investing platform CoinShares, cautioned that his firm’s data is only anecdotal — “as we can only rely on institutional investors telling us if they have purchased our ETPs” — but “we are seeing an increasing number of investment funds get in contact to discuss potentially adding Bitcoin and other crypto assets to their portfolios,” he told Cointelegraph, further explaining:

“Two years ago, the same funds thought Bitcoin was a crazy idea; a year ago, they wanted to discuss it further; and today, they are becoming increasingly anxious that they will lose clients if they do not invest.”

The key investment rationale, Butterfill added, “seems to be diversification and a monetary policy/inflation hedge.”

This participation may not necessarily be from the most traditional of institutional investors — i.e., pension funds or insurance companies — but skewed more toward family offices and funds of funds, according to Lennard Neo, head of research at Stack Funds, “but we do see an increase in risk appetite and interest, particularly so for specific crypto sectors — NFTs, DeFi, etc. — and broader mandates outside of just Bitcoin.” Stack Funds is getting two to three times more requests from investors than what it was getting early in the third quarter, he told Cointelegraph.

Why now?

Why the apparent heightened institutional interest? There are myriad reasons ranging from “the speculative to those who want to hedge against global macro uncertainties,” said Neo. But several have recently declared that they viewed “blockchain and crypto becoming an integral part of a global digital economy.”

Freddy Zwanzger, co-founder and chief data officer of blockchain data platform Anyblock Analytics GmbH, saw a certain amount of fear of missing out, or FOMO, at play here, telling Cointelegraph, “Where in the past, crypto investments were a risk for managers — it could go wrong — now it increasingly becomes a risk not to allocate at least some portion of the portfolio into crypto, as stakeholders will have examples from other institutions that did allocate and benefited greatly.”

The fact that large financial companies like Mastercard and Visa are beginning to support crypto on their networks and even purchasing nonfungible tokens has only intensified the FOMO, Zwanzger suggested.

“Interest from institutional investors and family offices has been rising gradually throughout the year,” Vladimir Vishnevskiy, director and co-founder at St. Gotthard Fund Management AG, told Cointelegraph. “The approval of the BTC ETF in October only exacerbated this trend, as now there is a much easier path to gaining this exposure.” Inflation worries are high on the agenda of many institutional investors, “and crypto is seen as a good hedge for this along with gold.”

Public companies looking at crypto for their balance sheets

What about corporations? Have more been purchasing Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies for their corporate treasuries?

Brandon Arvanaghi, CEO of Meow — a firm that enables corporate treasury participation in crypto markets — told Cointelegraph that he is seeing a new receptivity on the part of corporate chief financial officers vis-a-vis crypto, particularly in the wake of the global pandemic:

“When inflation is at 2% and interest rates are reasonable, corporate treasurers don’t think about looking into alternative assets. [...] COVID flipped the world on its head, and inflationary pressures are making corporate treasurers not only open to but actively seek alternative yield sources.”

“From our vantage point, we’re seeing more companies buy crypto to diversify their corporate treasuries,” commented Mónica. In addition, “Banks are reaching out to us to meet the demand for these types of services, which indicates a bigger trend beyond just companies adding crypto to their balance sheet. [...] It means soon, more people will have direct access to crypto through the financial instruments they already use.”

Macro trends are encouraging companies to add crypto to their balance sheets, Marc Fleury, CEO and co-founder of fintech firm Two Prime, told Cointelegraph. “Consider the fact that liquid corporate cash for U.S. publicly traded companies has soared from $1 trillion in 2020 to $4 trillion in 2021, and you can see why many are looking for new places to deploy this extra cash and why this trend will not abate.”

Meanwhile, the number of publicly traded companies that have announced they are holding Bitcoin has risen from 14 this time last year to 39 today, with the total amount held at $13.7 billion, said Butterfill.

Speaking of corporations, are more companies ready to accept crypto as payment for their products and services? Recently, Tesla was rumored to be on the verge of accepting BTC as payment for its cars (again).

Mónica told Cointelegraph, “Fintechs are reaching out to us to help them support not only Bitcoin, but a variety of digital assets, suggesting in the broader scheme, large companies are becoming more willing to support crypto payments.”

Fleury, for his part, was doubtful that cryptocurrencies — with one notable exception, stablecoins — would ever be widely used as a medium of exchange. “Volatile cryptos, like BTC and ETH are not good for payments. Period,” said Fleury. What makes crypto great as a reserve currency makes them poor monies of exchange, almost by design, he said, adding, “Stablecoins are another story.”

Is the stock-to-flow model persuasive?

Much has been made in the crypto community about the so-called stock-to-flow (S2F) model for predicting Bitcoin prices. Indeed, anonymous institutional investor PlanB’s S2F model predicted a BTC price of >$98,000 by the end of November. Do institutional investors take the stock-to-flow model seriously?

“Many institutional investors ask us this question,” Butterfill recounted, “but when they look more deeply into the model, they do not find it to be credible.” Stock-to-flow models often extrapolate future data points beyond a regression set’s current data range — a dubious practice, statistically speaking.

Furthermore, the method that compares an asset’s existing supply (“stock”) with the amount of new supply entering the market (“flow”) — through mining, for instance — “certainly hasn’t worked for other fixed-supply assets such as gold,” said Butterfill, adding, “In more recent years other approaches have been made to enhance the S2F model, but it is losing credibility with clients.”

“I don’t think institutions pay too much heed to the stock-to-flow model,” agreed Rathi, “though it is hard to malign it, as it has thus far proven to be quite accurate.” It seems to be more popular with retail traders than with institutions, he said. Vishnevskiy, on the other hand, wasn’t ready to dismiss stock-to-flow analysis so fast:

“Our fund looks at this model along with 40+ other metrics. It’s a good model, but not to be used alone. You have to use it along with other models and also consider the fundamentals and technical indicators.”

If not institutions, who is driving up prices?

Given that institutional participation in the latest crypto run-up appears to be mostly anecdotal at this point, it’s worth asking: If corporations and institutional investors haven’t been devouring most of the cryptocurrency floating about, who is?

“It makes sense that this has been a retail-led phenomenon,” answered Butterfill, “as we have witnessed the birth of a new asset class, and along with that comes confusion and hesitancy from regulators.” This regulatory uncertainty remains a continuing damper on institutional participation, he suggested, adding:

“In our most recent survey, regulations and corporate restrictions were the most-cited reason for not investing. The survey also found that those institutions with much more flexible mandates, such as family offices, have much larger positions compared to wealth managers.”

Still, even if ironclad data confirmation is lacking, many believe institutional participation in the digital asset market is growing. “As crypto security, technical infrastructure and regulatory clarity have improved over the years, it’s opened the door for broader institutional participation in the sector,” Mónica told Cointelegraph, adding:

“In the coming years, we’re going to see many payment rails through crypto, including stable coins and DeFi. I also expect we’ll see more interconnectivity between blockchain-based payment rails with legacy ones.”

For Fleury, the trend is clear. “Pension funds, endowments, sovereign funds and the like will adopt crypto in their portfolio in the next cycle.” They are cautious investors, however, and it takes time to conduct the necessary due diligence.

Related: Crypto and pension funds: Like oil and water, or maybe not?

But once institutional investors do commit, they tend to scale their commitments rapidly, he added. “We are still in the early innings of this institutional cycle. We will see a lot more interest from pension funds.”

At that point, a single $1-billion crypto transaction — like the one that occurred in late October, setting a record — will be an “everyday occurrence,” said Fleury.

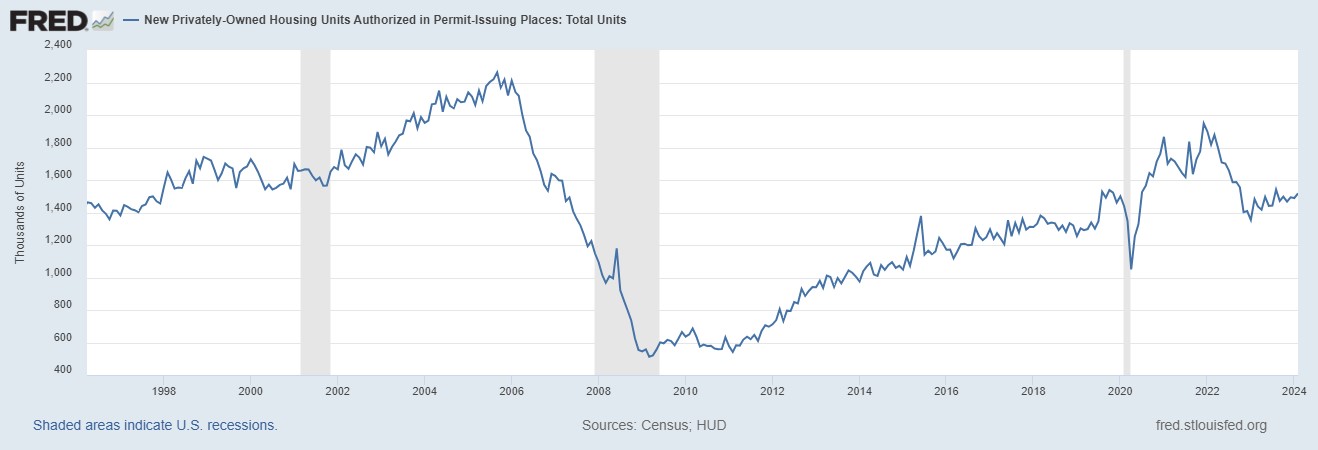

cryptocurrency bitcoin blockchain crypto btc pandemic etf crypto gold oilApartment permits are back to recession lows. Will mortgage rates follow?

If housing leads us into a recession in the near future, that means mortgage rates have stayed too high for too long.

In Tuesday’s report, the 5-unit housing permits data hit the same levels we saw in the COVID-19 recession. Once the backlog of apartments is finished, those jobs will be at risk, which traditionally means mortgage rates would fall soon after, as they have in previous economic cycles.

However, this is happening while single-family permits are still rising as the rate of builder buy-downs and the backlog of single-family homes push single-family permits and starts higher. It is a tale of two markets — something I brought up on CNBC earlier this year to explain why this trend matters with housing starts data because the two marketplaces are heading in opposite directions.

The question is: Will the uptick in single-family permits keep mortgage rates higher than usual? As long as jobless claims stay low, the falling 5-unit apartment permit data might not lead to lower mortgage rates as it has in previous cycles.

From Census: Building Permits: Privately‐owned housing units authorized by building permits in February were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1,518,000. This is 1.9 percent above the revised January rate of 1,489,000 and 2.4 percent above the February 2023 rate of 1,482,000.

When people say housing leads us in and out of a recession, it is a valid premise and that is why people carefully track housing permits. However, this housing cycle has been unique. Unfortunately, many people who have tracked this housing cycle are still stuck on 2008, believing that what happened during COVID-19 was rampant demand speculation that would lead to a massive supply of homes once home sales crashed. This would mean the builders couldn’t sell more new homes or have housing permits rise.

Housing permits, starts and new home sales were falling for a while, and in 2022, the data looked recessionary. However, new home sales were never near the 2005 peak, and the builders found a workable bottom in sales by paying down mortgage rates to boost demand. The first level of job loss recessionary data has been averted for now. Below is the chart of the building permits.

On the other hand, the apartment boom and bust has already happened. Permits are already back to the levels of the COVID-19 recession and have legs to move lower. Traditionally, when this data line gets this negative, a recession isn’t far off. But, as you can see in the chart below, there’s a big gap between the housing permit data for single-family and five units. Looking at this chart, the recession would only happen after single-family and 5-unit permits fall together, not when we have a gap like we see today.

From Census: Housing completions: Privately‐owned housing completions in February were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1,729,000.

As we can see in the chart below, we had a solid month of housing completions. This was driven by 5-unit completions, which have been in the works for a while now. Also, this month’s report show a weather impact as progress in building was held up due to bad weather. However, the good news is that more supply of rental units will mean the fight against rent inflation will be positive as more supply is the best way to deal with inflation. In time, that is also good news for mortgage rates.

Housing Starts: Privately‐owned housing starts in February were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1,521,000. This is 10.7 percent (±14.2 percent)* above the revised January estimate of 1,374,000 and is 5.9 percent (±10.0 percent)* above the February 2023 rate of 1,436,000.

Housing starts data beat to the upside, but the real story is that the marketplace has diverged into two different directions. The apartment boom is over and permits are heading below the COVID-19 recession, but as long as the builders can keep rates low enough to sell more new homes, single-family permits and starts can slowly move forward.

If we lose the single-family marketplace, expect the chart below to look like it always does before a recession — meaning residential construction workers lose their jobs. For now, the apartment construction workers are at the most risk once they finish the backlog of apartments under construction.

Overall, the housing starts beat to the upside. Still, the report’s internals show a marketplace with early recessionary data lines, which traditionally mean mortgage rates should go lower soon. If housing leads us into a recession in the near future, that means mortgage rates have stayed too high for too long and restrictive policy by the Fed created a recession as we have seen in previous economic cycles.

The builders have been paying down rates to keep construction workers employed, but if rates go higher, it will get more and more challenging to do this because not all builders have the capacity to buy down rates. Last year, we saw what 8% mortgage rates did to new home sales; they dropped before rates fell. So, this is something to keep track of, especially with a critical Federal Reserve meeting this week.

recession covid-19 fed federal reserve home sales mortgage rates recessionGovernment

Young People Aren’t Nearly Angry Enough About Government Debt

Young People Aren’t Nearly Angry Enough About Government Debt

Authored by The American Institute for Economic Research,

Young people sometimes…

Authored by The American Institute for Economic Research,

Young people sometimes seem to wake up in the morning in search of something to be outraged about. We are among the wealthiest and most educated humans in history. But we’re increasingly convinced that we’re worse off than our parents were, that the planet is in crisis, and that it’s probably not worth having kids.

I’ll generalize here about my own cohort (people born after 1981 but before 2010), commonly referred to as Millennials and Gen Z, as that shorthand corresponds to survey and demographic data. Millennials and Gen Z have valid economic complaints, and the conditions of our young adulthood perceptibly weakened traditional bridges to economic independence. We graduated with record amounts of student debt after President Obama nationalized that lending. Housing prices doubled during our household formation years due to zoning impediments and chronic underbuilding. Young Americans say economic issues are important to us, and candidates are courting our votes by promising student debt relief and cheaper housing (which they will never be able to deliver).

Young people, in our idealism and our rational ignorance of the actual appropriations process, typically support more government intervention, more spending programs, and more of every other burden that has landed us in such untenable economic circumstances to begin with. Perhaps not coincidentally, young people who’ve spent the most years in the increasingly partisan bubble of higher education are also the most likely to favor expanded government programs as a “solution” to those complaints.

It’s Your Debt, Boomer

What most young people don’t yet understand is that we are sacrificing our young adulthood and our financial security to pay for debts run up by Baby Boomers. Part of every Millennial and Gen-Z paycheck is payable to people the same age as the members of Congress currently milking this system and miring us further in debt.

Our government spends more than it can extract from taxpayers. Social Security, which represents 20 percent of government spending, has run an annual deficit for 15 years. Last year Social Security alone overspent by $22.1 billion. To keep sending out checks to retirees, Social Security goes begging to the Treasury Department, and the Treasury borrows from the public by issuing bonds. Bonds allow investors (who are often also taxpayers) to pay for some retirees’ benefits now, and be paid back later. But investors only volunteer to lend Social Security the money it needs to cover its bills because the (younger) taxpayers will eventually repay the debt — with interest.

In other words, both Social Security and Medicare, along with various smaller federal entitlement programs, together comprising almost half of the federal budget, have been operating for a decade on the principle of “give us the money now, and stick the next generation with the check.” We saddle future generations with debt for present-day consumption.

The second largest item in the budget after Social Security is interest on the national debt — largely on Social Security and other entitlements that have already been spent. These mandatory benefits now consume three quarters of the federal budget: even Congress is not answerable for these programs. We never had the chance for our votes to impact that spending (not that older generations were much better represented) and it’s unclear if we ever will.

Young Americans probably don’t think much about the budget deficit (each year’s overspending) or the national debt (many years’ deficits put together, plus interest) much at all. And why should we? For our entire political memory, the federal government, as well as most of our state governments, have been steadily piling “public” debt upon our individual and collective heads. That’s just how it is. We are the frogs trying to make our way in the watery world as the temperature ticks imperceptibly higher. We have been swimming in debt forever, unaware that we’re being economically boiled alive.

Millennials have somewhat modest non-mortgage debt of around $27,000 (some self-reports say twice that much), including car notes, student loans, and credit cards. But we each owe more than $100,000 as a share of the national debt. And we don’t even know it.

When Millennials finally do have babies (and we are!) that infant born in 2024 will enter the world with a newly minted Social Security Number and $78,089 credit card bill for Granddad’s heart surgery and the interest on a benefit check that was mailed when her parents were in middle school.

Headlines and comments sections love to sneer at “snowflakes” who’ve just hit the “real world,” and can’t figure out how to make ends meet, but the kids are onto something. A full 15 percent of our earnings are confiscated to pay into retirement and healthcare programs that will be insolvent by the time we’re old enough to enjoy them. The Federal Reserve and government debt are eating the economy. The same interest rates that are pushing mortgages out of reach are driving up the cost of interest to maintain the debt going forward. As we learn to save and invest, our dollars are slowly devalued. We’re right to feel trapped.

Sure, if we’re alive and own a smartphone, we’re among the one percent of the wealthiest humans who’ve ever lived. Older generations could argue (persuasively!) that we have no idea what “poverty” is anymore. But with the state of government spending and debt…we are likely to find out.

Despite being richer than Rockefeller, Millennials are right to say that the previous ways of building income security have been pushed out of reach. Our earning years are subsidizing not our own economic coming-of-age, but bank bailouts, wars abroad, and retirement and medical benefits for people who navigated a less-challenging wealth-building landscape.

Redistribution goes both ways. Boomers are expected to pass on tens of trillions in unprecedented wealth to their children (if it isn’t eaten up by medical costs, despite heavy federal subsidies) and older generations’ financial support of the younger has had palpable lifting effects. Half of college costs are paid by families, and the trope of young people moving back home is only possible if mom and dad have the spare room and groceries to make that feasible.

Government “help” during COVID-19 resulted in the worst inflation in 40 years, as the federal government spent $42,000 per citizen on “stimulus” efforts, right around a Millennial’s average salary at that time. An absurd amount of fraud was perpetrated in the stimulus to save an economy from the lockdown that nearly ruined it. Trillions in earmarked goodies were rubber stamped, carelessly added to young people’s growing bill. Government lenders deliberately removed fraud controls, fearing they couldn’t hand out $800 billion in young people’s future wages away fast enough. Important lessons were taught by those programs. The importance of self-sufficiency and the dignity of hard work weren’t top of the list.

Boomer Benefits are Stagnating Hiring, Wages, and Investment for Young People

Even if our workplace engagement suffered under government distortions, Millennials continue to work more hours than other generations and invest in side hustles and self employment at higher rates. Working hard and winning higher wages almost doesn’t matter, though, when our purchasing power is eaten from the other side. Buying power has dropped 20 percent in just five years. Life is $11,400/year more expensive than it was two years ago and deficit spending is the reason why.

We’re having trouble getting hired for what we’re worth, because it costs employers 30 percent more than just our wages to employ us. The federal tax code both requires and incentivizes our employers to transfer a bunch of what we earned directly to insurance companies and those same Boomer-busted federal benefits, via tax-deductible benefits and payroll taxes. And the regulatory compliance costs of ravenous bureaucratic state. The price paid by each employer to keep each employee continues to rise — but Congress says your boss has to give most of the increase to someone other than you.

Federal spending programs that many people consider good government, including Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and health insurance for children (CHIP) aren’t a small amount of the federal budget. Government spends on these programs because people support and demand them, and because cutting those benefits would be a re-election death sentence. That’s why they call cutting Social Security the “third rail of politics.” If you touch those benefits, you die. Congress is held hostage by Baby Boomers who are running up the bill with no sign of slowing down.

Young people generally support Social Security and the public health insurance programs, even though a 2021 poll by Nationwide Financial found 47 percent of Millennials agree with the statement “I will not get a dime of the Social Security benefits I have earned.”

In the same survey, Millennials were the most likely of any generation to believe that Social Security benefits should be enough to live on as a sole income, and guessed the retirement age was 52 (it’s 67 for anyone born after 1959 — and that’s likely to rise). Young people are the most likely to see government guarantees as a valid way to live — even though we seem to understand that those promises aren’t guarantees at all.

Healthcare costs tied to an aging population and wonderful-but-expensive growth in medical technologies and medications will balloon over the next few years, and so will the deficits in Boomer benefit programs. Newly developed obesity drugs alone are expected to add $13.6 billion to Medicare spending. By 2030, every single Baby Boomer will be 65, eligible for publicly funded healthcare.

The first Millennial will be eligible to claim Medicare (assuming the program exists and the qualifying age is still 65, both of which are improbable) in 2046. As it happens, that’s also the year that the Boomer benefits programs (which will then be bloated with Gen Xers) and the interest payments we’re incurring to provide those benefits now, are projected to consume 100 percent of federal tax revenue.

Government spending is being transferred to bureaucrats and then to the beneficiaries of government spending who are, in some sense, your diabetic grandma who needs a Medicare-paid dialysis treatment, but in a much more immediate sense, are the insurance companies, pharma giants, and hospital corporations who wrote the healthcare legislation. Some percentage of every college graduate’s paycheck buys bullets that get fired at nothing and inflating the private investment portfolios of government contractors, with dubious, wasteful outcomes from the prison-industrial complex to the perpetual war machine.

No bank or nation in the world can lend the kind of money the American government needs to borrow to fulfill its obligations to citizens. Someone will have to bite the bullet. Even some of the co-authors of the current disaster are wrestling with the truth.

Forget avocado toast and streaming subscriptions. We’re already sensing it, but we haven’t yet seen it. Young people are not well-informed, and often actively misled, about what’s rotten in this economic system. But we are seeing the consequences on store shelves and mortgage contracts and we can sense disaster is coming. We’re about to get stuck with the bill.

Spread & Containment

There Goes The Fed’s Inflation Target: Goldman Sees Terminal Rate 100bps Higher At 3.5%

There Goes The Fed’s Inflation Target: Goldman Sees Terminal Rate 100bps Higher At 3.5%

Two years ago, we first said that it’s only a matter…

Two years ago, we first said that it's only a matter of time before the Fed admits it is unable to rsolve the so-called "last mile" of inflation and that as a result, the old inflation target of 2% is no longer viable.

At some point Fed will concede it has no control over supply. That's when we will start getting leaks of raising the inflation target

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) June 21, 2022

Then one year ago, we correctly said that while everyone was paying attention elsewhere, the inflation target had already been hiked to 2.8%... on the way to even more increases.

The new inflation target has been set to 2.8%. The rest is just narrative fill for the next 2 years. https://t.co/X1xYkecyPy

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) February 21, 2023

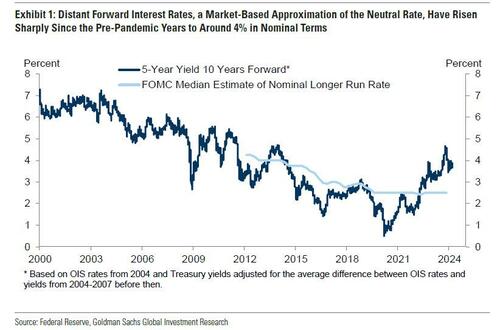

And while the Fed still pretends it can one day lower inflation to 2% even as it prepares to cut rates as soon as June, moments ago Goldman published a note from its economics team which had to balls to finally call a spade a spade, and concluded that - as party of the Fed's next big debate, i.e., rethinking the Neutral rate - both the neutral and terminal rate, a polite euphemism for the inflation target, are much higher than conventional wisdom believes, and that as a result Goldman is "penciling in a terminal rate of 3.25-3.5% this cycle, 100bp above the peak reached last cycle."

There is more in the full Goldman note, but below we excerpt the key fragments:

We argued last cycle that the long-run neutral rate was not as low as widely thought, perhaps closer to 3-3.5% in nominal terms than to 2-2.5%. We have also argued this cycle that the short-run neutral rate could be higher still because the fiscal deficit is much larger than usual—in fact, estimates of the elasticity of the neutral rate to the deficit suggest that the wider deficit might boost the short-term neutral rate by 1-1.5%. Fed economists have also offered another reason why the short-term neutral rate might be elevated, namely that broad financial conditions have not tightened commensurately with the rise in the funds rate, limiting transmission to the economy.

Over the coming year, Fed officials are likely to debate whether the neutral rate is still as low as they assumed last cycle and as the dot plot implies....

...Translation: raising the neutral rate estimate is also the first step to admitting that the traditional 2% inflation target is higher than previously expected. And once the Fed officially crosses that particular Rubicon, all bets are off.

... Their thinking is likely to be influenced by distant forward market rates, which have risen 1-2pp since the pre-pandemic years to about 4%; by model-based estimates of neutral, whose earlier real-time values have been revised up by roughly 0.5pp on average to about 3.5% nominal and whose latest values are little changed; and by their perception of how well the economy is performing at the current level of the funds rate.

The bank's conclusion:

We expect Fed officials to raise their estimates of neutral over time both by raising their long-run neutral rate dots somewhat and by concluding that short-run neutral is currently higher than long-run neutral. While we are fairly confident that Fed officials will not be comfortable leaving the funds rate above 5% indefinitely once inflation approaches 2% and that they will not go all the way back to 2.5% purely in the name of normalization, we are quite uncertain about where in between they will ultimately land.

Because the economy is not sensitive enough to small changes in the funds rate to make it glaringly obvious when neutral has been reached, the terminal or equilibrium rate where the FOMC decides to leave the funds rate is partly a matter of the true neutral rate and partly a matter of the perceived neutral rate. For now, we are penciling in a terminal rate of 3.25-3.5% this cycle, 100bps above the peak reached last cycle. This reflects both our view that neutral is higher than Fed officials think and our expectation that their thinking will evolve.

Not that this should come as a surprise: as a reminder, with the US now $35.5 trillion in debt and rising by $1 trillion every 100 days, we are fast approaching the Minsky Moment, which means the US has just a handful of options left: losing the reserve currency status, QEing the deficit and every new dollar in debt, or - the only viable alternative - inflating it all away. The only question we had before is when do "serious" economists make the same admission.

Meanwhile, nothing changes: total US debt jumps $57BN on March 15, to a record $34.543 trillion.

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) March 19, 2024

Three ways this ends: inflate it away, QE it all, or reserve status collapse

They now have.

And while we have discussed the staggering consequences of raising the inflation target by just 1% from 2% to 3% on everything from markets, to economic growth (instead of doubling every 35 years at 2% inflation target, prices would double every 23 years at 3%), and social cohesion, we will soon rerun the analysis again as the implications are profound. For now all you need to know is that with the US about to implicitly hit the overdrive of dollar devaluation, anything that is non-fiat will be much more preferable over fiat alternatives.

Much more in the full Goldman note available to pro subs in the usual place.

-

Spread & Containment7 days ago

Spread & Containment7 days agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex