Uncategorized

Racial Discrimination in Child Protective Services

Childhood experiences have an enormous impact on children’s long-term societal contributions. Experiencing childhood maltreatment is associated with…

Childhood experiences have an enormous impact on children’s long-term societal contributions. Experiencing childhood maltreatment is associated with compromised physical and mental health, decreased educational attainment and future earnings, and increased criminal activity. Child protective services is the government’s way of endeavoring to protect children. Foster care consequently has large potential effects on a child’s future education, earnings, and criminal activity. In this post, we draw on a recent study to document disparities in the likelihood that children of different races will be placed into foster care.

There are large racial disparities in involvement with child protective services (CPS). Although 28 percent of white children experience an investigation by CPS before age 18, the majority of Black children (53 percent) do (Kim et al., 2017). Black children are likewise twice as likely to spend time in foster care than white children (10 percent vs. 5 percent). Racial discrimination in this domain could exacerbate inequalities in many long-term outcomes. Yet racial disparities could also reflect differences in underlying risk of future child maltreatment. Attributing well-documented racial disparities to discrimination is thus a challenging task.

In a recent working paper, we conduct the first quasi-experimental study of racial disparities in the child protection system. We examine “unwarranted” racial disparities: that is, disparities in foster care placement rates among children who have an equal potential for being maltreated in the future if left at home. This is a natural measure of discrimination, since protecting children from future maltreatment is the sole reason why CPS decision-makers would place a child in foster care.

The difficulty in measuring unwarranted racial disparities is that a child’s potential for future maltreatment in the home is only partially observed: we can see future maltreatment only among children who were actually left in the home. For children who were placed into foster care, we cannot observe the subsequent maltreatment that would have occurred if they had been left at home. Thus, we cannot directly condition disparities on future maltreatment potential.

To overcome this measurement challenge, we leverage the quasi-random assignment of case investigators in Michigan—the setting of our study. Since each investigator receives a random subset of cases, we can ascertain their race-specific likelihood of placing a child in foster care based on their behavior in the cases assigned to them. Furthermore, by looking at the subsequent maltreatment rates of children assigned to investigators with very low placement rates, we can infer the average rates of maltreatment potential across all white and Black children in the state (see the chart below). Knowing these rates, we show, is enough to overcome the challenge of not observing future maltreatment potential of children placed into foster care.

Investigators’ Rate of Placement in Foster Care and the Subsequent Maltreatment Rates among Children Left at Home

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: This chart shows a binned scatter plot of foster care placement rates and subsequent maltreatment rates, among children left at home, across different quasi-randomly assigned investigators and by child race. The vertical intercept of each line-of-best fit estimates the average maltreatment potential among all children of that race.

Applying this approach, we find significant evidence of unwarranted racial disparity in foster care placement. Black children are 50 percent (1.7 percentage points) more likely to be placed into foster care than white children who have the exact same potential for experiencing subsequent maltreatment if left at home. Accounting for the risk of subsequent maltreatment is crucial: estimates of unwarranted racial disparity are nearly 90 percent larger than the placement disparity from an observational analysis that controls for child and investigation traits alone (see the next chart).

Unwarranted Racial Disparity Estimates, Relative to Observational Disparity

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: This chart shows estimates of unwarranted racial disparity for each of the three estimation approaches in the first chart above, along with an observational disparity which controls for child and investigation traits (dashed horizontal line). 95 percent confidence intervals are indicated by whiskers.

We further consider whether unwarranted racial disparities arise among children who are likely to be safe if left at home, or among those likely to experience maltreatment if left at home (see the chart below). We find that racial disparities in foster care placement are driven by children with a potential for subsequent maltreatment if left at home. Black children who would likely experience maltreatment if left at home are placed in foster care at twice the rate of white children in this subpopulation (12 percent versus 6 percent). In contrast, the foster care placement disparity is small and statistically insignificant in the subpopulation of children who are likely to be safe if left at home.

Unwarranted Racial Disparities and Foster Care Placement Rates for Children with and without Maltreatment Potential

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: This chart shows estimates of unwarranted racial disparity and foster care placement rates for each of the three estimation approaches in the first chart above, separately for children with and without future maltreatment potential. 95 percent confidence intervals are indicated by whiskers.

A higher placement rate among children who are likely to be maltreated if left at home may offer protection to those children, particularly if foster care improves long-run outcomes. Prior research in our specific setting finds that foster care improves outcomes for both Black and white children at risk of subsequent maltreatment if left at home: it lowers the likelihood of subsequent maltreatment and adult criminal justice contact while also improving educational outcomes. Together, this evidence suggests that higher placement rates among Black children may have a protective effect. Indeed, one might worry that white children are being “under-placed” relative to Black children.

There are active policy debates over ways to reduce racial disparities in foster care placement—as well as overall usage of foster care services. We find that lowering the foster care placement rate of Black children to equalize placement rates across races, as some have advocated for, would lead to a 7 percent increase in the number of Black children who are subsequently maltreated when left at home. On the other hand, using family preservation services that aim to reduce maltreatment while keeping families together may offer a possible solution. Greater efforts to increase outreach and take-up of these services among Black families may reduce the placement disparities while improving family well-being. Given the far-reaching consequences that child maltreatment and foster care can have—on physical and mental health, educational attainment, future earnings, and criminal activity—reducing racial disparities in these early-in-life outcomes can impact future societal inequities.

Natalia Emanuel is a research economist in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

E. Jason Baron is an assistant professor of economics at Duke University.

Joseph J. Doyle Jr. is the Erwin H. Schell Professor of Management and Applied Economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Peter Hull is a professor of economics at Brown University.

How to cite this post:

Natalia Emanuel, E. Jason Baron, Joseph J. Doyle Jr., and Peter Hull, “Racial Discrimination in Child Protective Services,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 16, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/10/racial-discrimination-in-child-protective-services/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Uncategorized

NY Fed Finds Medium, Long-Term Inflation Expectations Jump Amid Surge In Stock Market Optimism

NY Fed Finds Medium, Long-Term Inflation Expectations Jump Amid Surge In Stock Market Optimism

One month after the inflation outlook tracked…

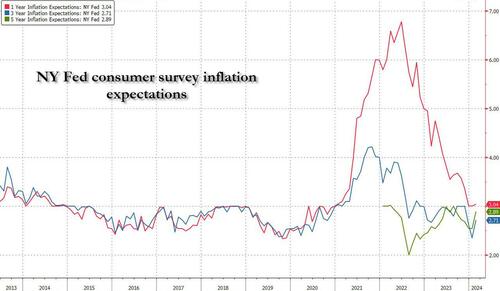

One month after the inflation outlook tracked by the NY Fed Consumer Survey extended their late 2023 slide, with 3Y inflation expectations in January sliding to a record low 2.4% (from 2.6% in December), even as 1 and 5Y inflation forecasts remained flat, moments ago the NY Fed reported that in February there was a sharp rebound in longer-term inflation expectations, rising to 2.7% from 2.4% at the three-year ahead horizon, and jumping to 2.9% from 2.5% at the five-year ahead horizon, while the 1Y inflation outlook was flat for the 3rd month in a row, stuck at 3.0%.

The increases in both the three-year ahead and five-year ahead measures were most pronounced for respondents with at most high school degrees (in other words, the "really smart folks" are expecting deflation soon). The survey’s measure of disagreement across respondents (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile of inflation expectations) decreased at all horizons, while the median inflation uncertainty—or the uncertainty expressed regarding future inflation outcomes—declined at the one- and three-year ahead horizons and remained unchanged at the five-year ahead horizon.

Going down the survey, we find that the median year-ahead expected price changes increased by 0.1 percentage point to 4.3% for gas; decreased by 1.8 percentage points to 6.8% for the cost of medical care (its lowest reading since September 2020); decreased by 0.1 percentage point to 5.8% for the cost of a college education; and surprisingly decreased by 0.3 percentage point for rent to 6.1% (its lowest reading since December 2020), and remained flat for food at 4.9%.

We find the rent expectations surprising because it is happening just asking rents are rising across the country.

At the same time as consumers erroneously saw sharply lower rents, median home price growth expectations remained unchanged for the fifth consecutive month at 3.0%.

Turning to the labor market, the survey found that the average perceived likelihood of voluntary and involuntary job separations increased, while the perceived likelihood of finding a job (in the event of a job loss) declined. "The mean probability of leaving one’s job voluntarily in the next 12 months also increased, by 1.8 percentage points to 19.5%."

Mean unemployment expectations - or the mean probability that the U.S. unemployment rate will be higher one year from now - decreased by 1.1 percentage points to 36.1%, the lowest reading since February 2022. Additionally, the median one-year-ahead expected earnings growth was unchanged at 2.8%, remaining slightly below its 12-month trailing average of 2.9%.

Turning to household finance, we find the following:

- The median expected growth in household income remained unchanged at 3.1%. The series has been moving within a narrow range of 2.9% to 3.3% since January 2023, and remains above the February 2020 pre-pandemic level of 2.7%.

- Median household spending growth expectations increased by 0.2 percentage point to 5.2%. The increase was driven by respondents with a high school degree or less.

- Median year-ahead expected growth in government debt increased to 9.3% from 8.9%.

- The mean perceived probability that the average interest rate on saving accounts will be higher in 12 months increased by 0.6 percentage point to 26.1%, remaining below its 12-month trailing average of 30%.

- Perceptions about households’ current financial situations deteriorated somewhat with fewer respondents reporting being better off than a year ago. Year-ahead expectations also deteriorated marginally with a smaller share of respondents expecting to be better off and a slightly larger share of respondents expecting to be worse off a year from now.

- The mean perceived probability that U.S. stock prices will be higher 12 months from now increased by 1.4 percentage point to 38.9%.

- At the same time, perceptions and expectations about credit access turned less optimistic: "Perceptions of credit access compared to a year ago deteriorated with a larger share of respondents reporting tighter conditions and a smaller share reporting looser conditions compared to a year ago."

Also, a smaller percentage of consumers, 11.45% vs 12.14% in prior month, expect to not be able to make minimum debt payment over the next three months

Last, and perhaps most humorous, is the now traditional cognitive dissonance one observes with these polls, because at a time when long-term inflation expectations jumped, which clearly suggests that financial conditions will need to be tightened, the number of respondents expecting higher stock prices one year from today jumped to the highest since November 2021... which incidentally is just when the market topped out during the last cycle before suffering a painful bear market.

Uncategorized

Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more

New Zillow research suggests the spring home shopping season may see a second wave this summer if mortgage rates fall

The post Homes listed for sale in…

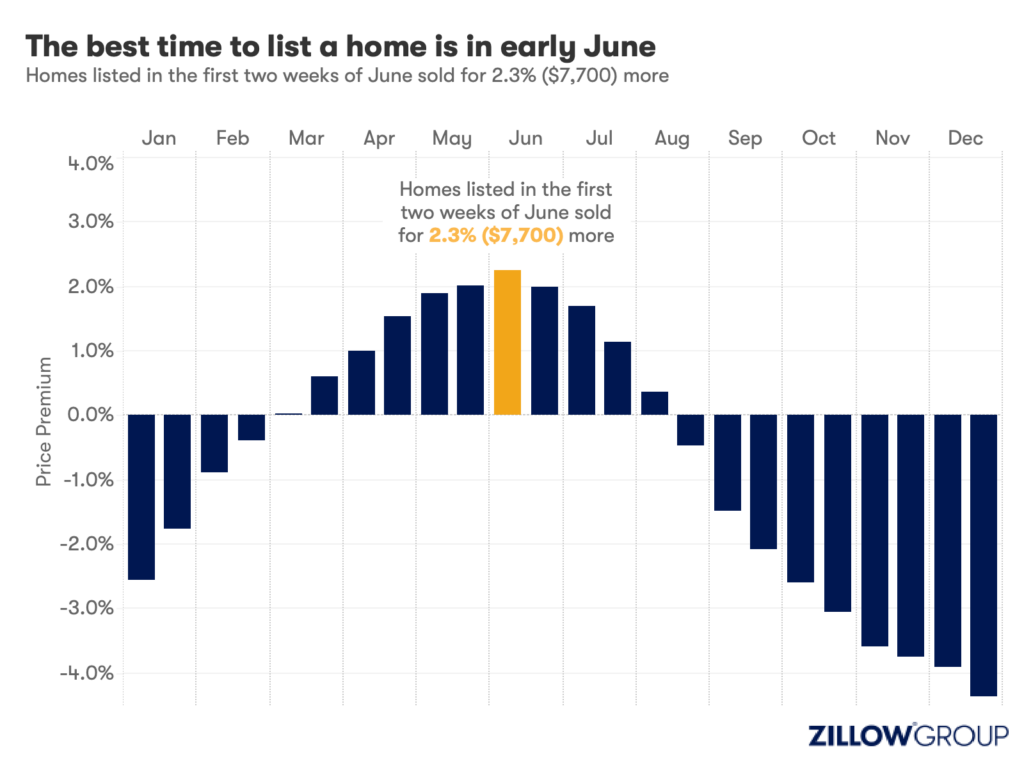

- A Zillow analysis of 2023 home sales finds homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more.

- The best time to list a home for sale is a month later than it was in 2019, likely driven by mortgage rates.

- The best time to list can be as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York and Philadelphia.

Spring home sellers looking to maximize their sale price may want to wait it out and list their home for sale in the first half of June. A new Zillow® analysis of 2023 sales found that homes listed in the first two weeks of June sold for 2.3% more, a $7,700 boost on a typical U.S. home.

The best time to list consistently had been early May in the years leading up to the pandemic. The shift to June suggests mortgage rates are strongly influencing demand on top of the usual seasonality that brings buyers to the market in the spring. This home-shopping season is poised to follow a similar pattern as that in 2023, with the potential for a second wave if the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates midyear or later.

The 2.3% sale price premium registered last June followed the first spring in more than 15 years with mortgage rates over 6% on a 30-year fixed-rate loan. The high rates put home buyers on the back foot, and as rates continued upward through May, they were still reassessing and less likely to bid boldly. In June, however, rates pulled back a little from 6.79% to 6.67%, which likely presented an opportunity for determined buyers heading into summer. More buyers understood their market position and could afford to transact, boosting competition and sale prices.

The old logic was that sellers could earn a premium by listing in late spring, when search activity hit its peak. Now, with persistently low inventory, mortgage rate fluctuations make their own seasonality. First-time home buyers who are on the edge of qualifying for a home loan may dip in and out of the market, depending on what’s happening with rates. It is almost certain the Federal Reserve will push back any interest-rate cuts to mid-2024 at the earliest. If mortgage rates follow, that could bring another surge of buyers later this year.

Mortgage rates have been impacting affordability and sale prices since they began rising rapidly two years ago. In 2022, sellers nationwide saw the highest sale premium when they listed their home in late March, right before rates barreled past 5% and continued climbing.

Zillow’s research finds the best time to list can vary widely by metropolitan area. In 2023, it was as early as the second half of February in San Francisco, and as late as the first half of July in New York. Thirty of the top 35 largest metro areas saw for-sale listings command the highest sale prices between May and early July last year.

Zillow also found a wide range in the sale price premiums associated with homes listed during those peak periods. At the hottest time of the year in San Jose, homes sold for 5.5% more, a $88,000 boost on a typical home. Meanwhile, homes in San Antonio sold for 1.9% more during that same time period.

| Metropolitan Area | Best Time to List | Price Premium | Dollar Boost |

| United States | First half of June | 2.3% | $7,700 |

| New York, NY | First half of July | 2.4% | $15,500 |

| Los Angeles, CA | First half of May | 4.1% | $39,300 |

| Chicago, IL | First half of June | 2.8% | $8,800 |

| Dallas, TX | First half of June | 2.5% | $9,200 |

| Houston, TX | Second half of April | 2.0% | $6,200 |

| Washington, DC | Second half of June | 2.2% | $12,700 |

| Philadelphia, PA | First half of July | 2.4% | $8,200 |

| Miami, FL | First half of June | 2.3% | $12,900 |

| Atlanta, GA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $8,700 |

| Boston, MA | Second half of May | 3.5% | $23,600 |

| Phoenix, AZ | First half of June | 3.2% | $14,700 |

| San Francisco, CA | Second half of February | 4.2% | $50,300 |

| Riverside, CA | First half of May | 2.7% | $15,600 |

| Detroit, MI | First half of July | 3.3% | $7,900 |

| Seattle, WA | First half of June | 4.3% | $31,500 |

| Minneapolis, MN | Second half of May | 3.7% | $13,400 |

| San Diego, CA | Second half of April | 3.1% | $29,600 |

| Tampa, FL | Second half of June | 2.1% | $8,000 |

| Denver, CO | Second half of May | 2.9% | $16,900 |

| Baltimore, MD | First half of July | 2.2% | $8,200 |

| St. Louis, MO | First half of June | 2.9% | $7,000 |

| Orlando, FL | First half of June | 2.2% | $8,700 |

| Charlotte, NC | Second half of May | 3.0% | $11,000 |

| San Antonio, TX | First half of June | 1.9% | $5,400 |

| Portland, OR | Second half of April | 2.6% | $14,300 |

| Sacramento, CA | First half of June | 3.2% | $17,900 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Second half of June | 2.3% | $4,700 |

| Cincinnati, OH | Second half of April | 2.7% | $7,500 |

| Austin, TX | Second half of May | 2.8% | $12,600 |

| Las Vegas, NV | First half of June | 3.4% | $14,600 |

| Kansas City, MO | Second half of May | 2.5% | $7,300 |

| Columbus, OH | Second half of June | 3.3% | $10,400 |

| Indianapolis, IN | First half of July | 3.0% | $8,100 |

| Cleveland, OH | First half of July | 3.4% | $7,400 |

| San Jose, CA | First half of June | 5.5% | $88,400 |

The post Homes listed for sale in early June sell for $7,700 more appeared first on Zillow Research.

federal reserve pandemic home sales mortgage rates interest ratesUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

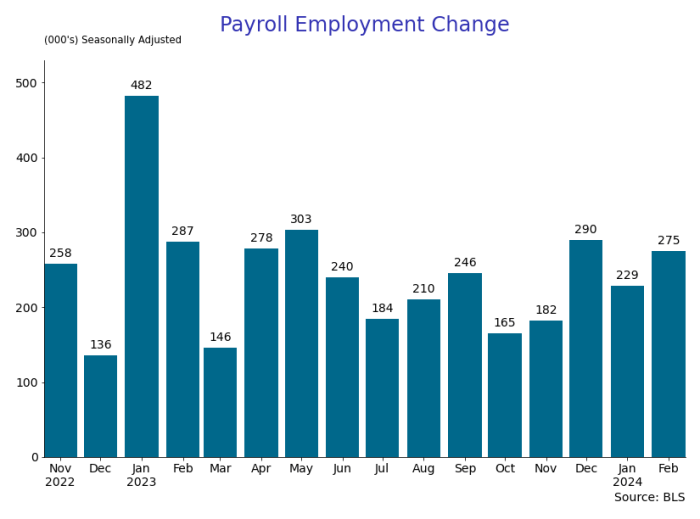

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemployment-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex