Uncategorized

Understanding mass incarceration in the US is the first step to reducing a swollen prison population

Experts still disagree about why the US prison population has grown so much over the last few decades. But crime is only one part of the problem.

The incarceration rate in the United States fell in 2021 to its lowest levels since 1995 – but the U.S. continues to imprison a higher percentage of its population than almost every other country.

The U.S. incarcerates 530 people for every 100,000 in its population, making it one of the world’s biggest jailers – just below El Salvador, Rwanda and Turkmenistan.

The U.S. actually had the greatest percentage of its population imprisoned until 2019. This followed steady growth in prison and jail populations in the 1970s, after a wave of “tough on crime” laws and policies swept the nation.

While there has been a growing recognition of the need to reduce mass incarceration, experts do not agree on what caused the ballooning prison population or the best path to reducing it.

As a former prosecutor and a researcher who studies the criminal justice system, I have found that understanding how the U.S. incarceration rate grew over the last few decades is the key to understanding its root causes – and what it will take to return to lower rates.

As I show in my new book, “Mass Incarceration Nation, How the United States Became Addicted to Prisons and Jails and How It Can Recover,” people tend to talk past one another when they discuss crime and punishment in the U.S. I think the public debate can improve if people develop a better understanding of how mass incarceration arose – and its tenuous connection to crime.

A growing prison population

The growth in mass incarceration began with a crime spike. Homicides, which averaged around 5,000 per year in the 1960s, shot up in the 1970s, reaching over 24,000 in 1991.

The crime spike sparked a bipartisan wave of punitive laws, the hiring of thousands of police officers and a “tough on crime” mindset that permeated every aspect of American criminal law. The system became more punitive, generating longer sentences, especially for repeat and violent offenses, as I show in my book.

Over time, this led to today’s aging prison population and many people being held long past the time they would have been released in other countries and at other times in this country’s history.

The number of people 55 or older in state and federal prisons increased 280% from 1999 to 2016, according to Pew research.

Different kinds of crime

But longer sentences are only one factor in America’s supersized incarceration rates.

There has also been a dramatic expansion of the kinds of crimes for which U.S. courts imprison people.

After the 1970s, more and more people went to prison for drug crimes and other offenses that rarely used to lead to prison time.

Serious violent crime, meanwhile, went back down in the 1990s. The crimes – like armed robbery and murder – that had sparked the march toward mass incarceration plummeted.

But prison populations didn’t drop.

As a prosecutor in Washington, D.C. in the early 2000s, I saw this change firsthand. Our caseloads were increasingly dominated by drug sales, drug possession and gun possession cases – cases which, not coincidentally, are typically the easiest to detect and prove. These changes were happening on a national level.

The number of people incarcerated in state prisons for homicide increased by over 300% between 1980 and 2010, reflecting the temporary spike in homicides and longer sentences for those convicted of that offense.

But the scale of the increases for other offenses, like drug crimes, is even larger – rising 1,147% over this time frame.

Speaking the same language

While prison populations are finally starting to go down, progress is slow. At the current rate, it will take decades to reach the low incarceration rates the U.S. had for most of its history.

This dip is partially because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted some states to release prisoners to avoid overcrowding and health risks. It is not clear that these recent reductions in the incarcerated population will continue.

I think that substantially reducing prison and jail populations will require better understanding of the link between incarceration and crime. It is not simply the case that incarceration goes up because people commit crime; instead, the story is much more complicated. That is because we use incarceration for two purposes: to obtain justice on behalf of victims and to try to change people’s behavior.

This distinction results in two kinds of cases flowing into this nation’s criminal courts.

First, there are cases that involve the most serious harm to individuals, like crimes of sexual violence and murder. Second, there are cases like drug offenses and weapons possession, which are not typically about obtaining justice for victims but are supposed to further policy goals like preventing drug use.

Changes in how we treat both kinds of cases contributed to the nation’s sky-high incarceration rate. American mass incarceration is a result of increasing sentence lengths for people who commit serious violent crimes. But it is also a product of a stunning expansion of the system’s reach in the form of more and more crimes leading to prison and jail.

Substantial progress at reducing the incarcerated population will require reversing both trends. First, returning sentence lengths for all offenses, including serious violent crime, to their historical norms. And second, resisting this country’s growing habit of relying on incarceration as a tool for achieving policy goals.

Jeffrey Bellin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

link pandemic covid-19Uncategorized

Bougie Broke The Financial Reality Behind The Facade

Social media users claiming to be Bougie Broke share pictures of their fancy cars, high-fashion clothing, and selfies in exotic locations and expensive…

Social media users claiming to be Bougie Broke share pictures of their fancy cars, high-fashion clothing, and selfies in exotic locations and expensive restaurants. Yet they complain about living paycheck to paycheck and lacking the means to support their lifestyle.

Bougie broke is like “keeping up with the Joneses,” spending beyond one’s means to impress others.

Bougie Broke gives us a glimpse into the financial condition of a growing number of consumers. Since personal consumption represents about two-thirds of economic activity, it’s worth diving into the Bougie Broke fad to appreciate if a large subset of the population can continue to consume at current rates.

The Wealth Divide Disclaimer

Forecasting personal consumption is always tricky, but it has become even more challenging in the post-pandemic era. To appreciate why we share a joke told by Mike Green.

Bill Gates and I walk into the bar…

Bartender: “Wow… a couple of billionaires on average!”

Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and other billionaires make us all much richer, on average. Unfortunately, we can’t use the average to pay our bills.

According to Wikipedia, Bill Gates is one of 756 billionaires living in the United States. Many of these billionaires became much wealthier due to the pandemic as their investment fortunes proliferated.

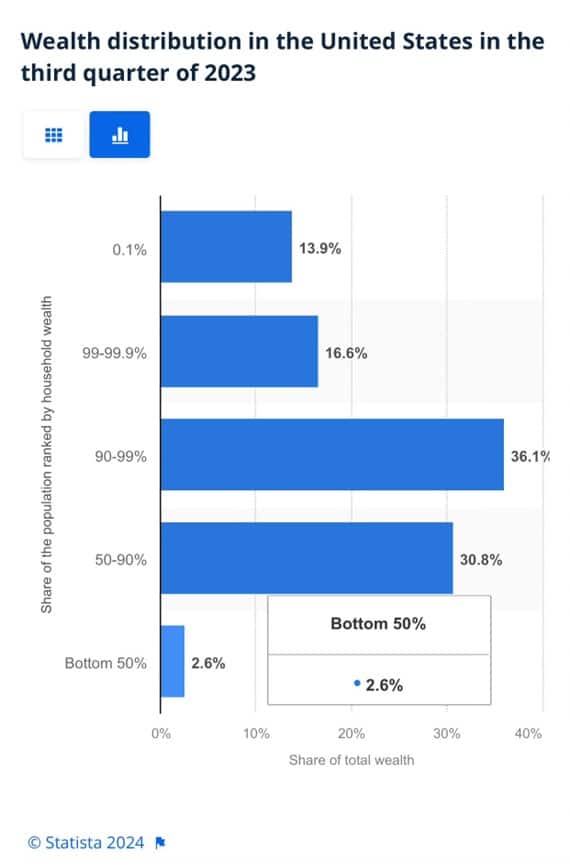

To appreciate the wealth divide, consider the graph below courtesy of Statista. 1% of the U.S. population holds 30% of the wealth. The wealthiest 10% of households have two-thirds of the wealth. The bottom half of the population accounts for less than 3% of the wealth.

The uber-wealthy grossly distorts consumption and savings data. And, with the sharp increase in their wealth over the past few years, the consumption and savings data are more distorted.

Furthermore, and critical to appreciate, the spending by the wealthy doesn’t fluctuate with the economy. Therefore, the spending of the lower wealth classes drives marginal changes in consumption. As such, the condition of the not-so-wealthy is most important for forecasting changes in consumption.

Revenge Spending

Deciphering personal data has also become more difficult because our spending habits have changed due to the pandemic.

A great example is revenge spending. Per the New York Times:

Ola Majekodunmi, the founder of All Things Money, a finance site for young adults, explained revenge spending as expenditures meant to make up for “lost time” after an event like the pandemic.

So, between the growing wealth divide and irregular spending habits, let’s quantify personal savings, debt usage, and real wages to appreciate better if Bougie Broke is a mass movement or a silly meme.

The Means To Consume

Savings, debt, and wages are the three primary sources that give consumers the ability to consume.

Savings

The graph below shows the rollercoaster on which personal savings have been since the pandemic. The savings rate is hovering at the lowest rate since those seen before the 2008 recession. The total amount of personal savings is back to 2017 levels. But, on an inflation-adjusted basis, it’s at 10-year lows. On average, most consumers are drawing down their savings or less. Given that wages are increasing and unemployment is historically low, they must be consuming more.

Now, strip out the savings of the uber-wealthy, and it’s probable that the amount of personal savings for much of the population is negligible. A survey by Payroll.org estimates that 78% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck.

More on Insufficient Savings

The Fed’s latest, albeit old, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households from June 2023 claims that over a third of households do not have enough savings to cover an unexpected $400 expense. We venture to guess that number has grown since then. To wit, the number of households with essentially no savings rose 5% from their prior report a year earlier.

Relatively small, unexpected expenses, such as a car repair or a modest medical bill, can be a hardship for many families. When faced with a hypothetical expense of $400, 63 percent of all adults in 2022 said they would have covered it exclusively using cash, savings, or a credit card paid off at the next statement (referred to, altogether, as “cash or its equivalent”). The remainder said they would have paid by borrowing or selling something or said they would not have been able to cover the expense.

Debt

After periods where consumers drained their existing savings and/or devoted less of their paychecks to savings, they either slowed their consumption patterns or borrowed to keep them up. Currently, it seems like many are choosing the latter option. Consumer borrowing is accelerating at a quicker pace than it was before the pandemic.

The first graph below shows outstanding credit card debt fell during the pandemic as the economy cratered. However, after multiple stimulus checks and broad-based economic recovery, consumer confidence rose, and with it, credit card balances surged.

The current trend is steeper than the pre-pandemic trend. Some may be a catch-up, but the current rate is unsustainable. Consequently, borrowing will likely slow down to its pre-pandemic trend or even below it as consumers deal with higher credit card balances and 20+% interest rates on the debt.

The second graph shows that since 2022, credit card balances have grown faster than our incomes. Like the first graph, the credit usage versus income trend is unsustainable, especially with current interest rates.

With many consumers maxing out their credit cards, is it any wonder buy-now-pay-later loans (BNPL) are increasing rapidly?

Insider Intelligence believes that 79 million Americans, or a quarter of those over 18 years old, use BNPL. Lending Tree claims that “nearly 1 in 3 consumers (31%) say they’re at least considering using a buy now, pay later (BNPL) loan this month.”More telling, according to their survey, only 52% of those asked are confident they can pay off their BNPL loan without missing a payment!

Wage Growth

Wages have been growing above trend since the pandemic. Since 2022, the average annual growth in compensation has been 6.28%. Higher incomes support more consumption, but higher prices reduce the amount of goods or services one can buy. Over the same period, real compensation has grown by less than half a percent annually. The average real compensation growth was 2.30% during the three years before the pandemic.

In other words, compensation is just keeping up with inflation instead of outpacing it and providing consumers with the ability to consume, save, or pay down debt.

It’s All About Employment

The unemployment rate is 3.9%, up slightly from recent lows but still among the lowest rates in the last seventy-five years.

The uptick in credit card usage, decline in savings, and the savings rate argue that consumers are slowly running out of room to keep consuming at their current pace.

However, the most significant means by which we consume is income. If the unemployment rate stays low, consumption may moderate. But, if the recent uptick in unemployment continues, a recession is extremely likely, as we have seen every time it turned higher.

It’s not just those losing jobs that consume less. Of greater impact is a loss of confidence by those employed when they see friends or neighbors being laid off.

Accordingly, the labor market is probably the most important leading indicator of consumption and of the ability of the Bougie Broke to continue to be Bougie instead of flat-out broke!

Summary

There are always consumers living above their means. This is often harmless until their means decline or disappear. The Bougie Broke meme and the ability social media gives consumers to flaunt their “wealth” is a new medium for an age-old message.

Diving into the data, it argues that consumption will likely slow in the coming months. Such would allow some consumers to save and whittle down their debt. That situation would be healthy and unlikely to cause a recession.

The potential for the unemployment rate to continue higher is of much greater concern. The combination of a higher unemployment rate and strapped consumers could accentuate a recession.

The post Bougie Broke The Financial Reality Behind The Facade appeared first on RIA.

recession unemployment pandemic economic recovery stimulus fed recession recovery interest rates unemployment stimulusUncategorized

Bitcoin on Wheels: The Story of Bitcoinetas

Meet the Bitcoinetas, a fleet of transformative vehicles on a mission to spread the bitcoin message everywhere they go. From Argentina to South Africa,…

You may have seen that picture of Michael Saylor in a bitcoin-branded van, with a cheerful guy right next to the car door. This one:

That car is the Bitcoineta European Edition, and the cheerful guy is Ariel Aguilar. Ariel is part of the European Bitcoineta team, and has previously driven another similar car in Argentina. In fact, there are currently five cars around the world that carry the name Bitcoineta (in some cases preceded with the Spanish definite article “La”).

Argentina: the original La Bitcoineta

The story of Bitcoinetas begins with the birth of 'La Bitcoineta' in Argentina, back in 2017. Inspired by the vibrancy of the South American Bitcoin community, the original Bitcoineta was conceived after an annual Latin American Conference (Labitconf), where the visionaries behind it recognized a unique opportunity to promote Bitcoin education in remote areas. Armed with a bright orange Bitcoin-themed exterior and a mission to bridge the gap in financial literacy, La Bitcoineta embarked on a journey to bring awareness of Bitcoin's potential benefits to villages and towns that often remained untouched by mainstream financial education initiatives. Operated by a team of dedicated volunteers, it was more than just a car; it was a symbol of hope and empowerment for those living on the fringes of financial inclusion.

Ariel was part of that initial Argentinian Bitcoineta team, and spent weeks on the road when the car became a reality. The original dream to bring bitcoin education even to remote areas within Argentina and other South American countries came true, and the La Bitcoineta team took part in dozens of local bitcoin meetups in the subsequent years.

One major hiccup came in late 2018, when the car was crashed into while parked in Puerto Madryn. The car was pretty much destroyed, but since the team was possessed by a honey badger spirit, nothing could stop them from keeping true to their mission. It is a testament to the determination and resilience of the Argentinian team that the car was quickly restored and returned on its orange-pilling quest soon after.

Over the more than 5 years that the Argentinian Bitcoineta has been running, it has traveled more than 80,000 kilometers - and as we’ll see further, it inspired multiple similar initiatives around the world.

Follow La Bitcoineta’s journey:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/labitcoineta

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bitcoineta/

El Salvador: Bitcoin Beach

In early 2021, the president of El Salvador passed the Bitcoin Law, making bitcoin legal tender in the country. The Labitconf team decided to celebrate this major step forward in bitcoin adoption by hosting the annual conference in San Salvador, the capital city of El Salvador. And correspondingly, the Argentinian Bitcoineta team made plans for a bold 7000-kilometer road trip to visit the Bitcoin country with the iconic Bitcoin car.

However, it proved to be impossible to cross so many borders separating Argentina and Salvador, since many governments were still imposing travel restrictions due to a Covid pandemic. So two weeks before the November event, the Labitconf team decided to fund a second Bitcoineta directly in El Salvador, as part of the Bitcoin Beach circular economy. Thus the second Bitcoineta was born.

The eye-catching Volkswagen minibus has been donated to the Bitcoin Beach team, which uses the car for the needs of its circular economy based in El Zonte.

Follow Bitcoin Beach:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Bitcoinbeach

South Africa: Bitcoin Ekasi

Late 2021 saw one other major development in terms of grassroots bitcoin adoption. On the other side of the planet, in South Africa, Hermann Vivier initiated the Bitcoin Ekasi project. “Ekasi” is a colloquial term for a township, and a township in the South African context is an underdeveloped urban area with a predominantly black population, a remnant of the segregationist apartheid regime. Bitcoin Ekasi emerged as an attempt to introduce bitcoin into the economy of the JCC Camp township located in Mossel Bay, and has gained a lot of success on that front.

Bitcoin Ekasi was in large part inspired by the success of the Bitcoin Beach circular economy back in El Salvador, and the respect was mutual. The Bitcoin Beach team thus decided to pass on the favor they received from the Argentinian Bitcoineta team, and provided funds to Bitcoin Ekasi for them to build a Bitcoineta of their own.

Bitcoin Ekasi emerged as a sister organization of Surfer Kids, a non-profit organization with a mission to empower marginalized youths through surfing. The Ekasi Bitcoineta thus partially serves as a means to get the kids to visit various surfer competitions in South Africa. A major highlight in this regard was when the kids got to meet Jordy Smith, one of the most successful South African surfers worldwide.

Coincidentally, South African surfers present an intriguing demographic for understanding Bitcoin due to their unique circumstances and needs. To make it as a professional surfer, the athletes need to attend competitions abroad; but since South Africa has tight currency controls in place, it is often a headache to send money abroad for travel and competition expenses. The borderless nature of Bitcoin offers a solution to these constraints, providing surfers with an alternative means of moving funds across borders without any obstacles.

Photo taken at the South African Junior Surfing Championships 2023. Back row, left to right:

Mbasa, Chuma, Jordy Smith, Sandiso. Front, left to right: Owethu, Sibulele.

To find out more about Bitcoineta South Africa and the non-profit endeavors it serves, watch Lekker Feeling, a documentary by Aubrey Strobel:

Follow Bitcoin Ekasi:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BitcoinEkasi

Fundraiser: https://support.bitcoinekasi.com/

Europe: Bitcoineta Europa

The European Bitcoineta started its journey in early 2023, with Ariel Aguilar being one of the main catalysts behind the idea. Unlike its predecessors in El Salvador and South Africa, the European Bitcoineta was not funded by a previous team but instead secured support from individual donors, reflecting a grassroots approach to spreading financial literacy.

The European Bitcoineta is a Mercedes box van adorned with a prominent Bitcoin logo and inspiring messages, and serves as a mobile hub for education and discussion at numerous European Bitcoin conferences and local meetups. Inside its spacious interior, both notable bitcoiners and bitcoin plebs share their insights on the walls, fostering a sense of camaraderie and collaboration.

Follow Bitcoineta Europa’s journey:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BitcoinetaEU

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bitcoinetaeu/

Ghana: Bitcoineta West Africa

Embed: https://youtu.be/8oWgIU17aIY?si=hrsKmMIA7lI6jX4k

Introduced in December 2023 at the Africa Bitcoin Conference in Ghana, the fifth Bitcoineta was donated to the Ghanaian Bitcoin Cowries educational initiative as part of the Trezor Academy program.

Bitcoineta West Africa was funded by the proceeds from the bitcoin-only limited edition Trezor device, which was sold out within one day of its launch at the Bitcoin Amsterdam conference.

With plans for an extensive tour spanning Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, and potentially other countries within the ECOWAS political and economic union, Bitcoineta West Africa embodies the spirit of collaboration and solidarity in driving Bitcoin adoption and financial inclusion throughout the Global South.

Follow Bitcoineta West Africa’s journey:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BitcoinetaWA

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bitcoinetawa/

—

All the Bitcoineta cars around the world share one overarching mission: to empower their local communities through bitcoin education, and thus improve the lives of common people that might have a strong need for bitcoin without being currently aware of such need. As they continue to traverse borders and break down barriers, Bitcoinetas serve as a reminder of the power of grassroots initiatives and the importance of financial education in shaping a more inclusive future. The tradition of Bitcoinetas will continue to flourish, and in the years to come we will hopefully encounter a brazenly decorated bitcoin car everywhere we go.

If the inspiring stories of Bitcoinetas have ignited a passion within you to make a difference in your community, we encourage you to take action! Reach out to one of the existing Bitcoineta teams for guidance, support, and inspiration on how to start your own initiative. Whether you're interested in spreading Bitcoin education, promoting financial literacy, or fostering empowerment in underserved areas, the Bitcoineta community is here to help you every step of the way. Together, we will orange pill the world!

This is a guest post by Josef Tetek. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

bitcoin btc pandemicUncategorized

Digital Currency And Gold As Speculative Warnings

Over the last few years, digital currencies and gold have become decent barometers of speculative investor appetite. Such isn’t surprising given the evolution…

Over the last few years, digital currencies and gold have become decent barometers of speculative investor appetite. Such isn’t surprising given the evolution of the market into a “casino” following the pandemic, where retail traders have increased their speculative appetites.

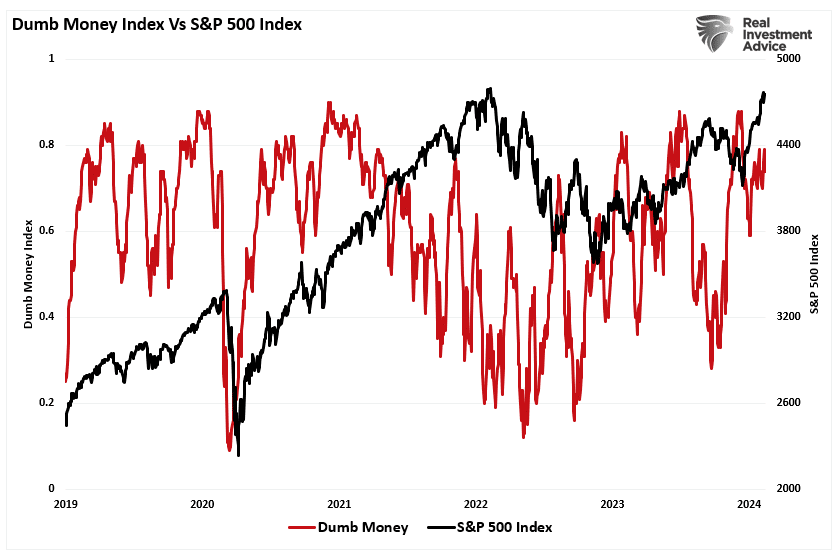

“Such is unsurprising, given that retail investors often fall victim to the psychological behavior of the “fear of missing out.” The chart below shows the “dumb money index” versus the S&P 500. Once again, retail investors are very long equities relative to the institutional players ascribed to being the “smart money.””

“The difference between “smart” and “dumb money” investors shows that, more often than not, the “dumb money” invests near market tops and sells near market bottoms.”

That enthusiasm has increased sharply since last November as stocks surged in hopes that the Federal Reserve would cut interest rates. As noted by Sentiment Trader:

“Over the past 18 weeks, the straight-up rally has moved us to an interesting juncture in the Sentiment Cycle. For the past few weeks, the S&P 500 has demonstrated a high positive correlation to the ‘Enthusiasm’ part of the cycle and a highly negative correlation to the ‘Panic’ phase.”

That frenzy to chase the markets, driven by the psychological bias of the “fear of missing out,” has permeated the entirety of the market. As noted in “This Is Nuts:”

“Since then, the entire market has surged higher following last week’s earnings report from Nvidia (NVDA). The reason I say “this is nuts” is the assumption that all companies were going to grow earnings and revenue at Nvidia’s rate. There is little doubt about Nvidia’s earnings and revenue growth rates. However, to maintain that growth pace indefinitely, particularly at 32x price-to-sales, means others like AMD and Intel must lose market share.”

Of course, it is not just a speculative frenzy in the markets for stocks, specifically anything related to “artificial intelligence,” but that exuberance has spilled over into gold and cryptocurrencies.

Birds Of A Feather

There are a couple of ways to measure exuberance in the assets. While sentiment measures examine the broad market, technical indicators can reflect exuberance on individual asset levels. However, before we get to our charts, we need a brief explanation of statistics, specifically, standard deviation.

As I discussed in “Revisiting Bob Farrell’s 10 Investing Rules”:

“Like a rubber band that has been stretched too far – it must be relaxed in order to be stretched again. This is exactly the same for stock prices that are anchored to their moving averages. Trends that get overextended in one direction, or another, always return to their long-term average. Even during a strong uptrend or strong downtrend, prices often move back (revert) to a long-term moving average.”

The idea of “stretching the rubber band” can be measured in several ways, but I will limit our discussion this week to Standard Deviation and measuring deviation with “Bollinger Bands.”

“Standard Deviation” is defined as:

“A measure of the dispersion of a set of data from its mean. The more spread apart the data, the higher the deviation. Standard deviation is calculated as the square root of the variance.”

In plain English, this means that the further away from the average that an event occurs, the more unlikely it becomes. As shown below, out of 1000 occurrences, only three will fall outside the area of 3 standard deviations. 95.4% of the time, events will occur within two standard deviations.

A second measure of “exuberance” is “relative strength.”

“In technical analysis, the relative strength index (RSI) is a momentum indicator that measures the magnitude of recent price changes to evaluate overbought or oversold conditions in the price of a stock or other asset. The RSI is displayed as an oscillator (a line graph that moves between two extremes) and can read from 0 to 100.

Traditional interpretation and usage of the RSI are that values of 70 or above indicate that a security is becoming overbought or overvalued and may be primed for a trend reversal or corrective pullback in price. An RSI reading of 30 or below indicates an oversold or undervalued condition.” – Investopedia

With those two measures, let’s look at Nvidia (NVDA), the poster child of speculative momentum trading in the markets. Nvidia trades more than 3 standard deviations above its moving average, and its RSI is 81. The last time this occurred was in July of 2023 when Nvidia consolidated and corrected prices through November.

Interestingly, gold also trades well into 3 standard deviation territory with an RSI reading of 75. Given that gold is supposed to be a “safe haven” or “risk off” asset, it is instead getting swept up in the current market exuberance.

The same is seen with digital currencies. Given the recent approval of spot, Bitcoin exchange-traded funds (ETFs), the panic bid to buy Bitcoin has pushed the price well into 3 standard deviation territory with an RSI of 73.

In other words, the stock market frenzy to “buy anything that is going up” has spread from just a handful of stocks related to artificial intelligence to gold and digital currencies.

It’s All Relative

We can see the correlation between stock market exuberance and gold and digital currency, which has risen since 2015 but accelerated following the post-pandemic, stimulus-fueled market frenzy. Since the market, gold and cryptocurrencies, or Bitcoin for our purposes, have disparate prices, we have rebased the performance to 100 in 2015.

Gold was supposed to be an inflation hedge. Yet, in 2022, gold prices fell as the market declined and inflation surged to 9%. However, as inflation has fallen and the stock market surged, so has gold. Notably, since 2015, gold and the market have moved in a more correlated pattern, which has reduced the hedging effect of gold in portfolios. In other words, during the subsequent market decline, gold will likely track stocks lower, failing to provide its “wealth preservation” status for investors.

The same goes for cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin is substantially more volatile than gold and tends to ebb and flow with the overall market. As sentiment surges in the S&P 500, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies follow suit as speculative appetites increase. Unfortunately, for individuals once again piling into Bitcoin to chase rising prices, if, or when, the market corrects, the decline in cryptocurrencies will likely substantially outpace the decline in market-based equities. This is particularly the case as Wall Street can now short the spot-Bitcoin ETFs, creating additional selling pressure on Bitcoin.

Just for added measure, here is Bitcoin versus gold.

Not A Recommendation

There are many narratives surrounding the markets, digital currency, and gold. However, in today’s market, more than in previous years, all assets are getting swept up into the investor-feeding frenzy.

Sure, this time could be different. I am only making an observation and not an investment recommendation.

However, from a portfolio management perspective, it will likely pay to remain attentive to the correlated risk between asset classes. If some event causes a reversal in bullish exuberance, cash and bonds may be the only place to hide.

The post Digital Currency And Gold As Speculative Warnings appeared first on RIA.

bonds pandemic sp 500 equities stocks bitcoin currencies gold-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International5 days ago

International5 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International5 days ago

International5 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges